Dog-faced water snake feeding

Table of Contents

| Dog-faced water snake seen in a river in Tioman (Taken by Lee Bee Yan 2011) |

Name

Scientific Name: Cerberus rynchops (Schneider, 1799)Common Name: Dog-faced water snake; Asian Bockadam snakeIt was first described as Hydrus rynchops by Schneider in 1799 in Historiae amphiborum naturalis et literariae.It was later revised as Cerberus rynchops by Gyi, 1970.

Etymology

The word, Cerberus, means a "three-headed doglike monster with serpent's tail that guarded the gated of hades, hell-hound".The species epithet, rynchops, is probably derived from a combination of the Greek words, rhyncho = "nose, snout, or muzzle", and ops = eye.(Reference from: Brown, R. W., 1956. Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington. Pp 275, 659.)

Taxonavigation

Order: SquamataFamily: Homalopsidae

Genus: Cerberus Cuvier, 1829

Species: Cerberus rynchops (Schneider, 1799)

Family Homalopsidae (Oriental-Australian rear-fanged water snakes) consists of 10 genera with a total of 34 species of snakes. (Gyi, 1970; Voris et al., 2002; Alfraro et al., 2004; Murphy, 2007; Alfraro et al., 2008)

Genus Cerberus Cuvier, 1829

There are 3 species within this genus (Gyi, 1970).- Cerberus australis (Gray, 1842)

- Cerberus microlepis Boulenger, 1896

- Cerberus rynchops (Schneider, 1799)

These 3 species can be differentiated based on their morphological traits, the biogeographical regions as well as the genetic divergence showed in the study by Alfaro et al., 2004.

Diagnosis

For Cerberus rynchops, its head shields are not defined clearly and the parietals scales are fragmented into small scales. It is not easy to distinguished C. rynchops from C. australis morphologically. The head scales that are anterior to the jaws for C. australis are not keel unlike in C. rynchops. C. rynchops can be distinguished from C. microlepsis by the difference in the number of dorsal scales along the middle of the body where C. rynchops has between 21-25 while C. microlepsis has between 27-29. |

| Top view of the head of Dog-faced water snake (RMBR specimen, Taken by Lee Bee Yan, 2011) |

Description

Original description of Cerberus rynchops (Schneider, 1799):Schneider, J. G., 1799. Historiae amphibiorum naturalis et literariae. Impressus Ienae, Jena: Sumtibus Friederici Frommanni. Pp 246-247. (View PDF)Elongated head that is distinct from the neck. Small eyes that are situated on the top of the head, near the snout as seen in the photo on the right. The frontal scales (in purple) are small in size and the parietals scales (in yellow) are fragmented into smaller scales. There is a dark stripe through the snout to neck across each eye.

There are between 22-27 dorsal scale rows on the neck, 21-25 dorsal scales rows on the middle of the body (where normally its either 23 or 25), and 16-20 dorsal scales rows on the back of the body (where its normally 17). Scales are strongly keeled.

|

| Variation in colouration of the Dog-faced water snake. (Taken by Lee Bee Yan, 2010 & 2011) |

The snakes exhibit variation in colouration and pattern. Dorsum (Top surface of the body) of the snake is usually uniformly grayish (A) or brownish (B) in colour with dark cross bands that will extend to its tail. The underside of the snake is yellowish in colour.

Adults can grow up to 1m in total length.

Biology

|

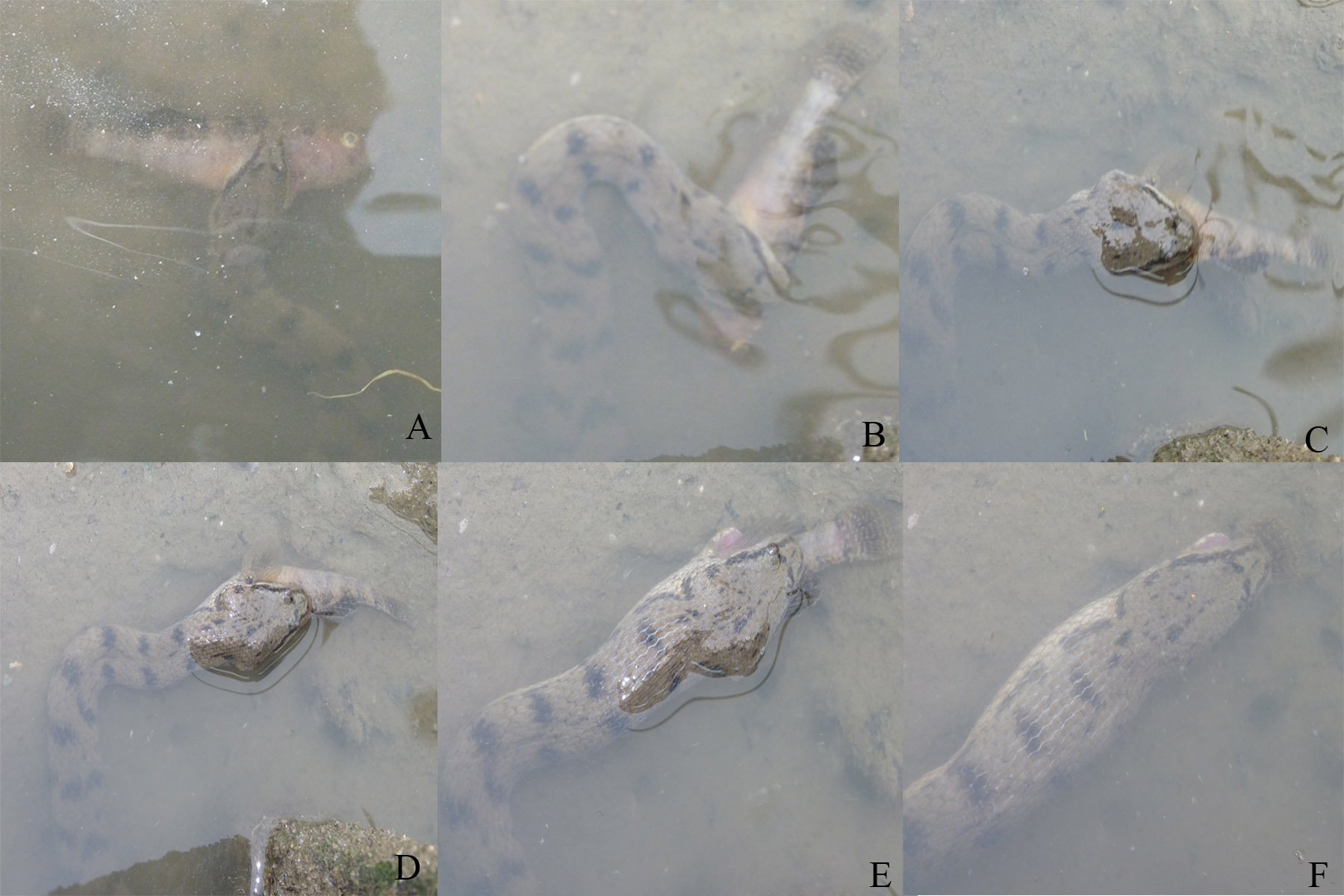

| A-F shows the swallowing of fish prey. (Photo taken by Lee Bee Yan, 2010) |

Diet

C. rynchops are generalist piscivores (Jayne et al., 1988; Voris and Murphy, 2002). They are noted to be an opportunistic predators for fish prey (Murphy, 2007).After striking at its fish prey, it will move the fish backwards to the side of its mouth and the fish would be hold perpendicular to its neck (Jayne et al., 1988). This action can be seen in the photo (left) and the video (below) which shows the movement of the snake after striking the fish prey.

They are observe to hunt more actively in the evening and night time.

Video showing the behaviour after striking a prey (Taken by Mary-ruth Low, 2011)

Venom

The venom of this snake is considered to be mildly venomous (Baker and Lim, 2008; Ng et al., 2008). Based on the experiment done by Alcock and Rogers (1902), the venom fluid from an adult snake is able to kill small mammals in full dosage. A new group of snake venom proteins was also identified from this species and more research on the function of the snake venom is still ongoing (OmPraba et al., 2010).Reproduction

This species give birth to live young. There are a number of literature on the snake reproduction throughout the years in various location. It shows that the litter size of the species ranges from 5 to 38 (Murphy, 2007). The seasonality for the reproduction appears to differ with locality. As suggested by Jayne et al. (1988), the reproduction for the snake population in Malaysia is aseasonal. For the snake population in Singapore, the reproduction is aseasonal as well (Chim, pers. comm.).Behaviour

The snake was noted to be docile and would not exhibit any aggressive character when approached (wall, 1918). Based on personal observation, the snake also exhibit a docile nature and would not show aggression when approach in field.An interesting motion was noted from this snake and that is, this species of snake was observe to be able to jump. However, this jumping action is not its usual mode of locomotion and such instances are very rare. Such a jumping action could be because the snake was threatened and could be used as a mode for escape (Chim, pers. comm.)

This jumping action was capture in a documentary by BBC, "Life in Cold blood", featuring Sir David Attenborough. This jumping action, however, was only observe and documented once.

There has been no known research done thus far. Therefore, there is no conclusive evidence as to why the snake is able to jump.

Video on the right shows the jumping action of the Dog-faced water snake (From 2:24 to 2:47). The part of the documentary featuring the jumping snake and the crab-eating water snake was shot in Singapore's mangroves.

Ecology

Natural enemy

Predators of C. rynchops was observed to be crustaceans as the snake scales was found within the gut contents of the mangrove mud crab, Scylla serrata (Voris and Murphy, 2002).Humans are known to kill the snake and is considered to be its major predator (Murphy, 2007). The dog-faced water snake are sometimes entangles in fishing nets and would drown or the fishermen would kill the snake (Murphy, 2007). The snake's skin are also collected for used in the leather trade for ornamental purposes (Murphy, 2007).

Habitat type

|

| Sightings of Dog-faced water snake in freshwater pond and stream in Tioman. (Taken by Lee Bee Yan, 2011) |

It is a coastal marine species that is commonly found in brackish waters in the mangroves, estuaries, coastal zones and mudflats (Gyi, 1970; Tweedie, 1983; Jayne et al., 1988; Karns et al., 2000). This species has been showed to have salt gland which allows it to be able to tolerate and adapt to the salt water environment (Dunson & Dunson, 1979).

Even though the snake are frequently found in brackish water as well as salt water, they are also found in freshwater occasionally. Based on field observation in Tioman, this species of snake was seen in freshwater streams both during the day and night.

|

| Various sightings of Dog-faced water snake during low tide, in the day, in Singapore's mangroves (Taken by Lee Bee Yan, 2010 & 2011) |

In Singapore, they are commonly sighted in the mangroves and mudflats. Based on field observation, during the day, they can be found hiding in burrows or underneath debris such as cloth or canvas sheet.

Based on a study of the dog-faced water snake in Singapore by Karns et al. (2002), it was shown that the snake is normally associated with open muddy pools area within the mangrove. During low tide, they are also observed to move about in tidal pool or along the small stream within the mangrove.

Distribution

It is widely distributed in Southeast Asia (Tweedie, 1988; Jayne et al., 1988; Alfraro et al., 2004; Alfraro et al., 2008). It was recorded from the far west of India, to far east of Sunda Islands; they are also found in the Palau Islands (Gyi, 1970).Map showing the distribution range of Dog-faced water snake. (Reference from Murphy, 2007)The pointer shows the type locality of the species.

Distribution within Singapore

It is native to Singapore and is commonly found within the mangroves and mudflats in Singapore (Grandison, 1978; Tweedie, 1983; Lim and Lim, 2002; Ng and Sivasothi, 2002; Lim and Baker, 2008; Ng et al., 2008; Das, 2010).Status of Cerberus rynchops

According to IUCN red list, the conservation status of this species is of least concern. However, there are still potential threat to this species as it was collected for its skin in the past for the leather trade in some countries. It is not known whether such practices are still continued today due to a lack in data.Conservation actions

This species is listed in Appendix III of CITES. It is also protected under The Indian Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972.Type information

According to Gyi (1970), this species was described by Schneider (1799) from the illustration by Russell (1796), plate 17.Cerberus rynchops is the type species of the genus Cerberus Cuvier, 1829 (Gyi, 1970).

[The species that was used to describe the genus; a representative of the genus]

Type locality: Ganjam, India.

[The location where the specimen of this species was first described from.]

Link to other pages on Cerberus rynchops

Wild fact sheet by Ria Tan on Cerberus rynchopsEcology Asia: Dog-faced Water Snake by Nick Baker

Literature and references

Alcock, A. & L. Rogers, 1902. On the toxic properties of the saliva of certain "non-poisonous' Colubrines. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, 70: 446-454. (View PDF)Alfaro, M. E., D. R. Karns, H. K. Voris, E. Abernathy & S. L. Sellins, 2004. Phylogeny of Cerberus (Serpentes: Homalopsinae) and phylogeography of Cerberus rynchops: diversification of a coastal marine snake in Southeast Asia. Journal of Biogeography, 31: 1277-1292.

Alfraro, M. E., D. R. Karns, H. K. Voris, C. D. Brock & B. L. Stuart, 2008. Phylogeny, evolutionary history, and biogeography of Oriental-Australian rear-fanged water snakes (Colubroidea: Homalopsidae) inferred from mitochondrial and nuclear DNA sequences. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 46: 576-593.

Baker, N. & K. K. P. Lim, 2008. Wild animals of Singapore: A photographic guide to Mammals, Reptiles, Amphibians and freshwater fishes. Draco Publishing and Distribution Pte. Ltd., Singapore. p. 109.

Chim C. K., November 2011. Enquire about Cerberus rynchops. [Personal communication]

Dunson, W. A. & M. K. Dunson, 1979. A possible new salt gland in a Marine Homalopsid snake (Cerberus rynchops). Coperis, 4: 661-672.

Das, I., 2010. A field guide to the reptiles of South-East Asia. New Holland Publishers Ltd., United Kingdom. p. 325

Grandison, A. G. C., 1978. Snakes of West Malaysia and Singapore. Ann. Naturhistor. Mus. Wien, 81: 283-303. (View PDF)

Gyi, K. K., 1970. A revision of Colubrid snakes of the subfamily Homalopsinae. University of Kansas Publications, Museum of Natural History, 20(2): 47-223. (View PDF for Cerberus rynchops)

IUCN Red List-Cerberus rynchops. URL: http://www.iucnredlist.org/apps/redlist/details/176680/0 Accessed on 1 November 2011.

Jayne, B. C., H. K. Voris & K. B. Heang, 1988. Diet, feeding behavior, growth, and numbers of a population of Cerberus rynchops (Serpentes: Homalopsinae) in Malaysia. Fieldiana Zoology, New Series, 50 (View PDF)

Karns, D. R., A. O'Bannon, H. K. Voris & A. W., Lee, 2000. Biogeographical implications of mitochndrial DNA variation in the Bockadam snake (Cerberus rynchops, Serpentes: Homalopsinae) in Southeast Asia. Journal of Biogeography, 27: 391-402.

Karns, D. R., H. K. Voris & T. G. Goodwin, 2002. Ecology of Oriental-Australian rear-fanged water snakes (Colubridae: Homalopsinae) in the Pasir Ris Park Mangrove forest, Singapore. The Raffles Bulletin of Zoology, 50(2): 487-498. (View PDF)

Lim, K. K. P. & F. L. K. Lim, 2002. A guide to the amphibians and reptiles of Singapore. Revised edition, Singapore Science Centre, Singapore. p. 76.

Murphy, J.C. An annotated bibliography to the Oriental-Australasian rear-fanged water snakes (Serpentes: Homalopsidae).

URL: http://www.jcmnaturalhistory.com/COMLIT.pdf. Accessed on 8 November 2011.

Murphy, J. C., 2007. Homalopsid snakes: Evolution in the mud. Krieger Publishing Company, Malabar, Florida. Pp 39-50, 63-72.

Murphy, J. C., 2011. The nomenclature and systematics of some Australiasian Homalopsid snakes (Squamata: Serpentes: Homalopsidae). The Raffles Bulletin of Zoology, 59(2): 229-236. (View PDF)

Ng, P. K. L. & N. Sivasothi, 2002. Guide to the mangroves of Singapore II: Animal diversity. Second edition, Singapore Science Centre, Singapore. p. 144.

Ng, P. K. L., Wang L. K. & K. K. P. Lim, 2008. Private lives: An exposé of Singapore's Mangroves. The Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research, Singapore. p.164.

OmPraba, G., A. Chapeaurouge, R. Doley, K. R. Devi, P. Padmanaban, C. Venkatraman, D. Velmurugan, Q. Lin & R. M. Kini, 2010. Identification of a novel family of snake venom proteins Veficolins from Cerberus rynchops using a venom gland transcriptomics and proteomics approach. Journal of Proteome Research, 9: 1882-1893.

Schneider, J. G., 1799. Historiae amphibiorum naturalis et literariae. Impressus Ienae, Jena: Sumtibus Friederici Frommanni. Pp 246-247.

Tweedie, M. W. F., 1983. The snakes of Malaya. Third edition, Singapore National Printers Pte. Ltd., Singapore.Pp 23,103, 104, 157.

Voris, H. K. & J. C. Murphy, 2002. The prey and predators of Homalopsine snakes. Journal of Natural History, 36: 1621-1632. (View PDF)

Voris, H. K., M. E. Alfraro, D. R. Karns, G. L. Starnes, E. Thompson & J. C. Murphy, 2002. Phylogenetic relationships of the Oriental-Autralian Rear-Fanged Water Snakes (Colubridae: Homalopsinae) based on mitochondrial DNQ sequences. Copeia, 4: 906-915.

Wall, F., 1918. A popular treatise of the common Indian snakes. Journal of the Bombay Natural HIstory Society, 26: 89-97. (View PDF)

Comments

If you have any additional information or queries regarding this species of snakes, feel free to drop your comments below.HTML Comment Box is loading comments...