|

|

| An individual atop Jelutong Tower in Singapore's Central Catchment Nature Reserve. |

Table of Contents

A. Species Description

|

| The head of the Paradise Tree Snake is distinct from its cylindrical body. |

|

|

| Coloured spots evident on each dorsal scale. |

Underside of the snake with parallel lines across. |

|

| An individual with red coloration. Copyright 2010 ThailandSnakes.com (Used with permission). |

Other confusing species?

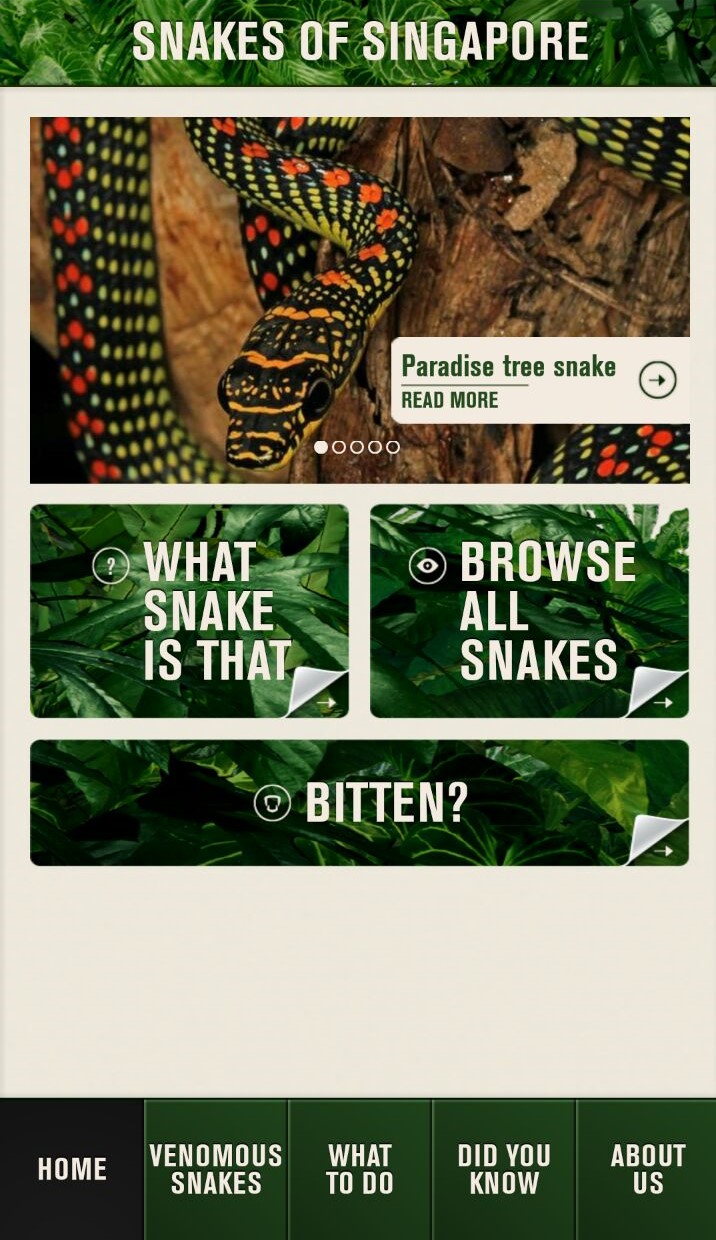

In Singapore, there are some snakes that may be confused with the Paradise Tree Snake at first glance. The table below shows how they can be distinguished. To identify more snakes, there is a free "Snakes of Singapore" mobile application that offers pictures and useful identification tools (more details in the "Snake Encounters & Safety" section).

|

|

|

| Twin-barred Gliding Snake. Image by Ron Yeo. (Permission pending) |

Female Wagler’s Pit Viper. Image by Ron Yeo. (Permission pending) |

Golden Tree Snake. Image Copyright 2010 ThailandSnakes.com (Used with permission). |

| The only other native gliding snake, they can be distinguished by the body coloration which are predominantly red with black and white bands. |

The females of this species have similarly colored bodies, but can be distinguished by the more triangular shape of the head and arrangement of the yellow spots along the body. |

This closely related species is not native to Singapore but at least 2 sightings have been recorded, perhaps from the pet trade.[5] [6] They can distinguished by looking at the scales along the body, with a thin black line down the middle of each scale's yellow or green spot, while the Paradise Tree Snake has simple dark scales with a light yellow or green spot in the middle.[7] |

B. Ecology & Conservation Status

|

| Species distribution, whith the three subspecies represented being C. p. paradisi (green), C. p. celebensis (yellow) and C. p. variabilis (blue). Map illustrated by: Lim Jia Ying, approximated according to GBIF georeferenced data and IUCN location description. Base Map of Southeast Asia adapted from: Sankakukei (free map). |

This species usually occurs in primary and secondary tropical rainforest of elevation below 1500m.[8] However, past records indicate their occurrence in human-modified habitats as well. Such areas include coconut plantations next to forests, tree-shaded gardens, rural villages, and attics of old houses.[9] They are found in many parts of Southeast Asia, extending southwards of southern Myanmar and southern Thailand, all the way to Sulawesi and Philippines. Countries where they are native to are Brunei Darussalam; India (Andaman Islands); Indonesia (Bali, Jawa, Kalimantan, Sumatera); Malaysia (Peninsular Malaysia, Sabah, Sarawak); Myanmar; Philippines; Thailand and Singapore.

Where can they be found in Singapore?

Paradise Tree Snakes are fairly common and can exist in forest, scrubland, mangroves and urban gardens.[10] They are known to be found at Central Catchment Nature Reserve, Pasir Ris Park, Pulau Ubin, Rifle Range Road, and Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve.[11] They are sometimes also found in urban areas close to their natural habitat. When in the natural habitat, snakes can be hiding under rocks or fallen trees, basking in the sun, or atop plants and trees.

Conservation Status & Threats

| Screen capture of IUCN classification of Chrysopelea paradisi (Paradise Tree Snake). |

As of 2014, The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species classified the Paradise Tree Snake to be a species of ‘Least Concern’, because of its wide distribution, stable population, existence within several protected areas, and its tolerance to some habitat changes. It is caught for the international pet trade on a small scale, although Thailand imposes an export ban on live snakes. Globally, this species faces no significant threat, but extensive deforestation may present localized risks for areas like Cebu in Philippines.[12]

In Singapore

In highly urbanized Singapore, there has been several cases of Paradise Tree Snake entering buildings and indoor spaces like the basement of Outram Park MRT[13] , as well as Nanyang Technological University's Hall of Residence 15[14] In some unfortunate cases, the Paradise Tree Snakes became victims of abuse[15] and roadkills.[16] [17] Such threats are avoidable, requiring citizens to be thoughtful and aware of appropriate measures to take upon snake encounters. If snakes are found in urban environments and need to be relocated back to their natural habitat, it is advised to contact experts from ACRES for help, or you may refer to AVA's advisory for more details. Please extend your kindness to all wildlife, Singapore is home to them, as much as it is for us human beings.

| A badly injured victim of roadkill seen at Punggol End. Image by Rachel Lee (2016). (Used with permission) |

As a predator of small animals, Paradise Tree Snakes are secondary or tertiary consumers in the food chain, and thus serve to maintain the prey populations. In turn, the Paradise Tree Snake may be preyed on by larger birds of prey, mammals and even larger snakes, especially since its mild venom is unlikely to forestall their much bigger predators. Little else is known about the ecological role.

C. Behaviour

Gliding behaviour

Paradise Tree Snakes are AMAZING GLIDERS! But wait, gliding is not the same as flying?

| Flying |

Gliding |

| Locomotor behaviour in air that requires active control of aerodynamic forces. |

Controlled descent by organisms that harness gravitational potential energy to do useful aerodynamic work. [18] |

| Flight is common to most birds, winged insects, and bats. |

Gliding vertebrates include some arboreal frogs (Rhacophorus), “flying dragons” (Draco), “flying squirrels”and “flying fishes” (Exocoetus).[19] |

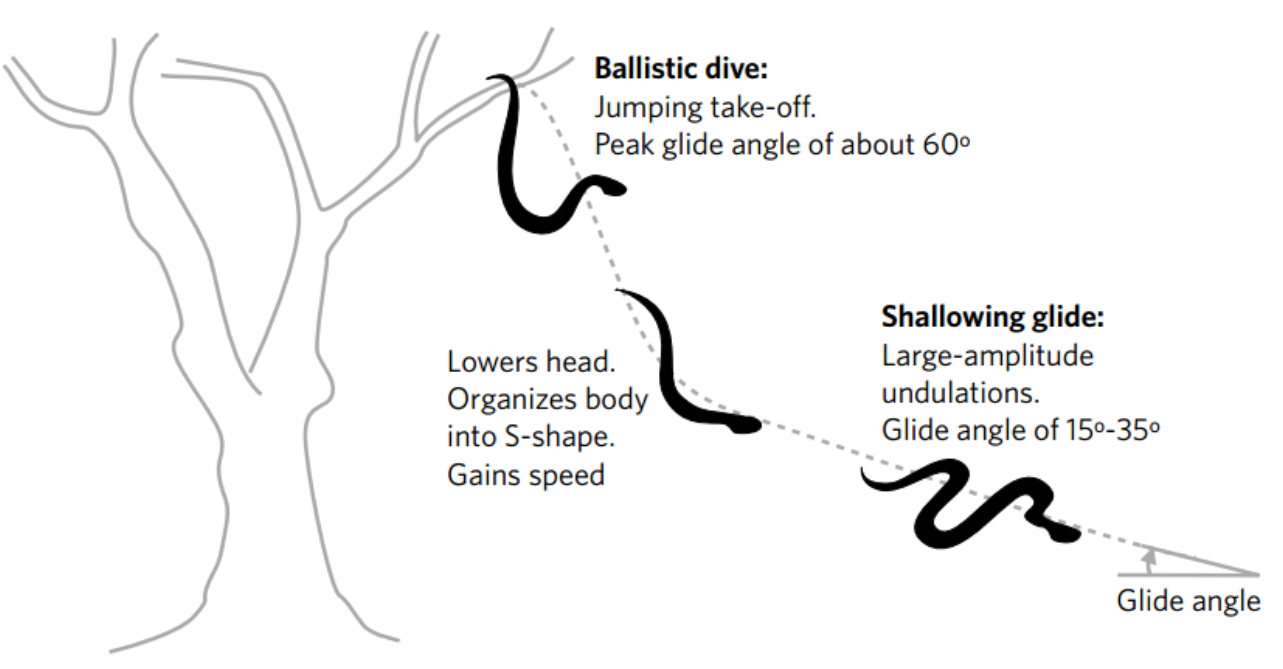

Stage 1: Takeoff

After climbing a tree of suitable height (average observed height of 9m),[23] the snake would jump, dive, or fall from a branch. Oftentimes, they would engage in a J-loop jumping takeoff before their dive. Initially, the forebody of the snake dangles in a J-shape while the posterior (back-half) body loops around the branch to maintain grip. Then it arcs its forebody up and forward, and upon releasing its grip, becomes airborne with peak glide angle of 60 degrees!

|

| Illustration of a typical glide trajectory. Image from Krishnan et al. (2014)[24] , under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 License. |

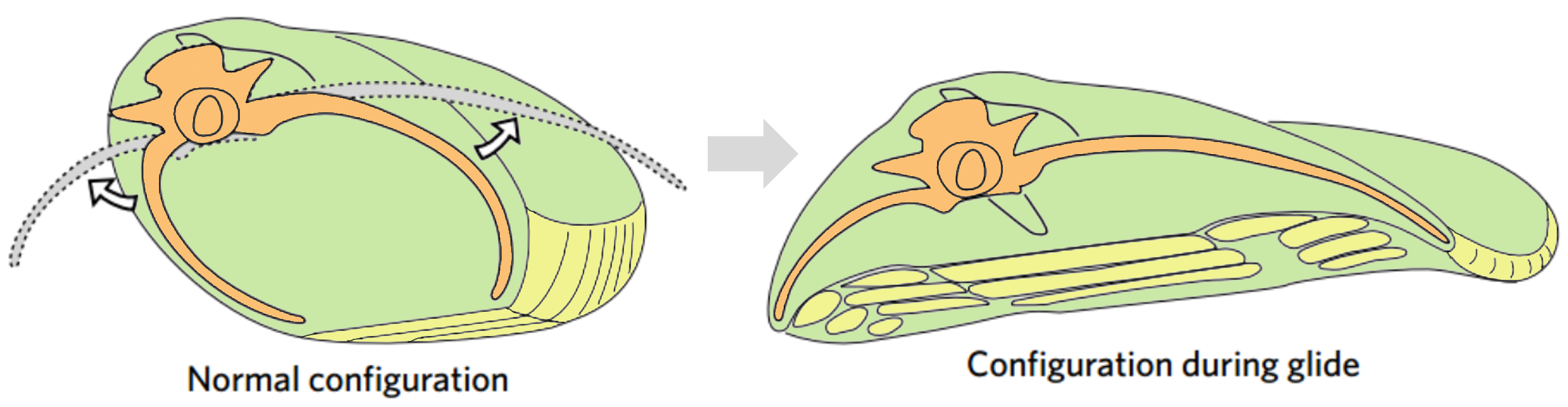

The snake rapidly changes shape from a round to a flattened triangular cross-section while in the air, making it aerodynamically favourable for gliding. The snake’s width at mid-body easily becomes twice the usual width when at rest! The flattening of the body involves movement of the ribs, and ultimately forms a concave shape at the cross section.

|

| Image of snake’s body cross section (coloration added to distinguish ribs [orange] and underside of the body [yellow]) adapted from: Krishnan et al. (2014), under CC BY 4.0 license. |

While in the air, the snakes moves its head from side to side while the posterior body moves up and down, thereby creating waves that appear as curves along its body. During this period, the glide becomes less steep. They may also execute turns in mid-air, a feat that has not been observed in other gliding snakes!

Stage 4: Landing

Just before landing, the snake orientates the tail downward, allowing the tail to hit the ground first. The head is the last to contact the ground, minimizing the impact forces on it. If landing on a branch, a wrapping motion around the branch is induced upon contact. In field observations, they cover about 10m horizontally, when jumping from a height of about 9m.

Now check out these videos to watch the snakes execute their amazing glides!

| Video documenting the flight of an individual in slow-motion. |

Video of Locomotor trials conducted in Singapore, demonstrating the behaviours of the snakes. |

Feeding behaviour

Snakes are carnivorous, and the Paradise Tree Snake is no exception. They prefer eating tree-dwelling lizards but may opportunistically feed on rodents, small birds and bats.[25] While some of their prey may be larger than its body size, these snakes are equipped with rear fangs, allowing them deliver venom into their prey. Fangs are specialized teeth with venom gland, and are on the upper jaws of snakes. Their rear fangs are positioned towards the back of the upper jaws, as opposed to some other cobras and vipers that have front fangs positioned near the front of their upper jaws. Because of the backward position of their fangs, Paradise Tree Snake have to bite their prey and grind the venom into the prey’s wound through the grooves on their fangs,[26] making ‘chewing motions’ as it does so. |

| Screengrab from a video by Chan Boon Hong (2016), showing an individual ingesting a lizard. In this position, the snake employs constriction to hold the prey in place, while its mild venom takes effect. |

Reproductive behaviour

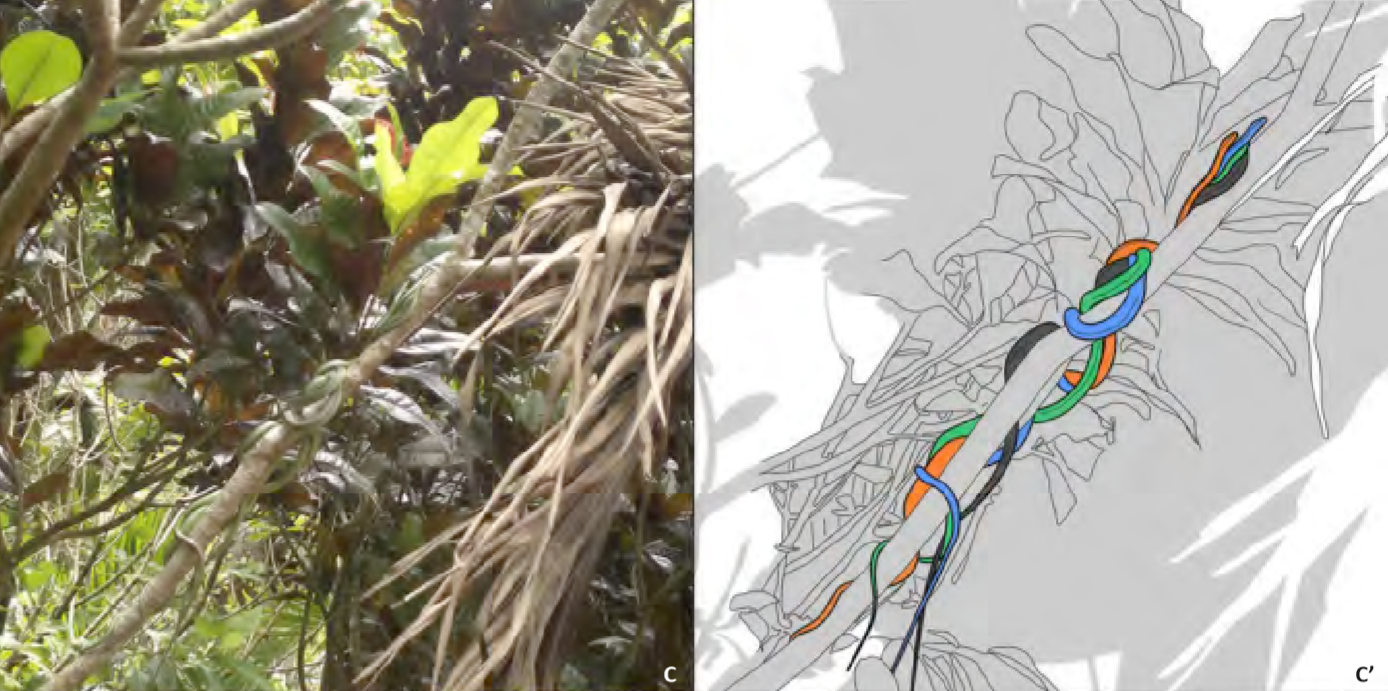

Snakes are oviparous, meaning they lay eggs, of clutch size between five and eight.[27] While not much is known about their reproduction habits, the eggs produced in Thailand usually hatch in May and June[28] , and hatchlings are approximately 15-20cm, with similar pattern and brighter coloration.[29] A rare courtship behaviour between a female and three males was documented, featuring elongate courtship configuration.[30] In that multi-male courtship, the males lured by the female’s pheromone trail were clustered around her body and followed her pace as she moved slowly through the habitat. |

| The female (illustrated in dark grey on the right diagram) in the lead, followed closely by the three males (illustrated in green, blue, and orange). As seen by the position of bodies and tails along the branch, the courtship involves significant overlap of all participants. Image from Kaiser (2016) , under CC BY 4.0 |

D. Snake encounters & Safety

If you're lucky enough to spot these amazing creatures, but are concerned for the safety of yourself and people around you, here are some things to consider.| They are mildly venomous snake meaning they can only paralyze small prey but are largely harmless to humans. Note that snakes can be venomous (they inject toxic substances into prey by biting or stinging), but not poisonous (toxic when consumed or touched)! The position of their rear fangs requires them to have a good grasp of the pry in their (small) mouth for a considerable duration, so it is unlikely that humans would be intentionally bitten by them or have venom injected. Nevertheless, do not go too close or provoke them! |

|

| The typical diagnostic features[31] of Paradise Tree Snakes' bite are mild to moderate pain, some local bruising, numbness, bleeding, but no necrosis of systemic effects.A recorded case of a bite on a young man's index finger was a source of 'moderate pain' but the bite had mild local effect.[32] The bite occured when he moved it using a broomstick, provoking the snake to bite his finger. At the hospital, he was administered gentle wound irrigation, intramuscular anti-tetanus toxoid injection, oral diclofenac sodium as analgesia, intravenous cloxacillin 1 gm stat, and oral cloxacillin upon discharge. The pain was well-controlled and the wound recovered well. |

Bitten by unidentified snake?

Here's what you should do if so! [33] [34]1. Move away from the snake to prevent being attacked again.

2. Keep still with the bitten limb positioned below the heart to reduce the flow of venom.

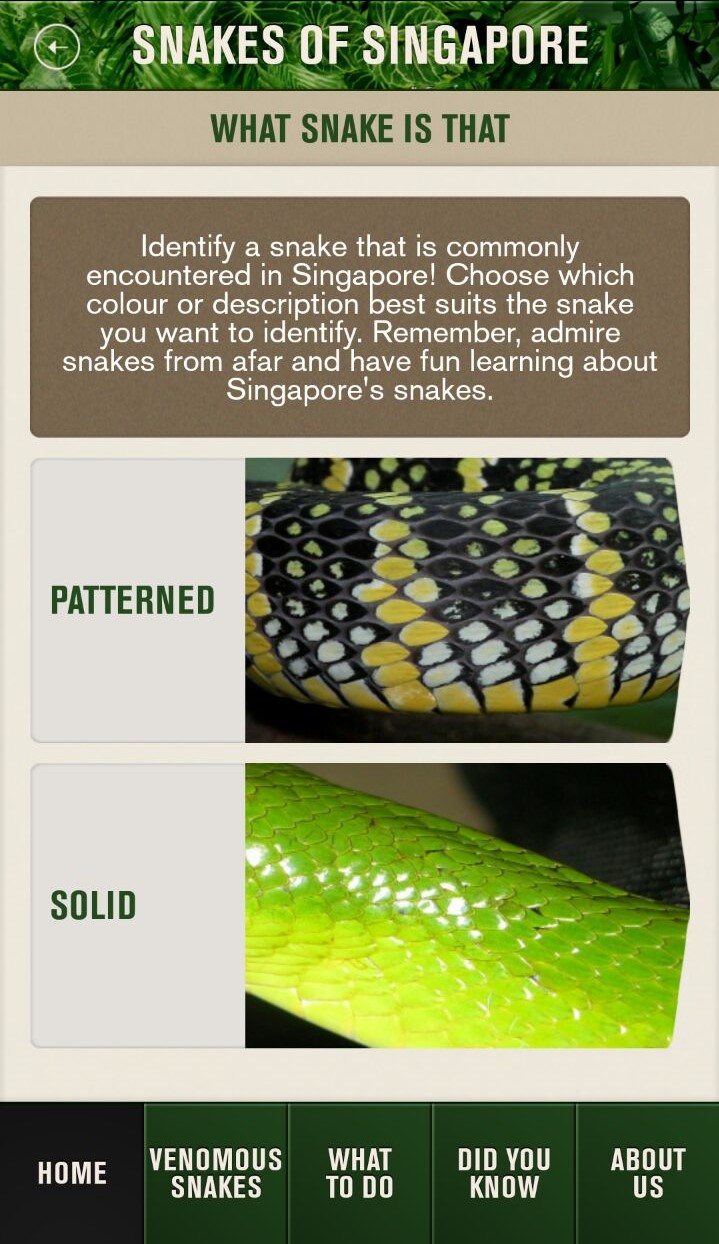

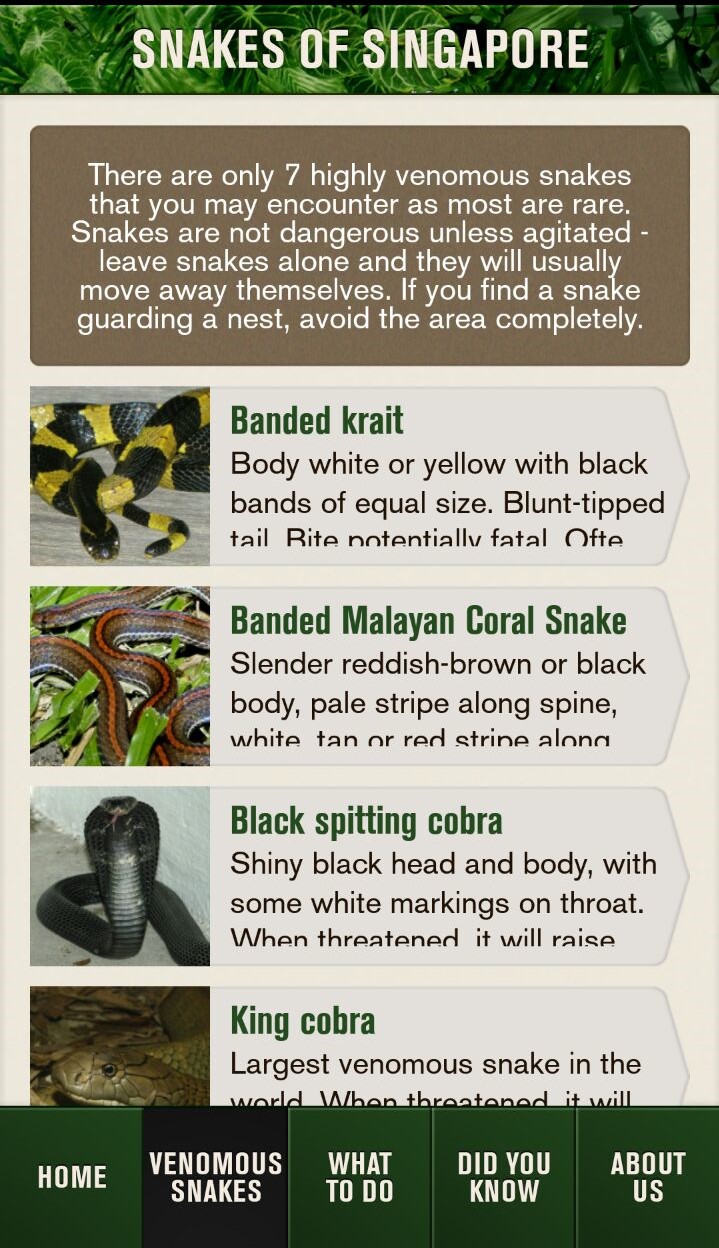

3. Try to identify the snake, to check if it is highly venomous or not. A free downloadable mobile application "Snakes of Singapore" offers identification tools to do so easily.

|

|

|

| Screen capture of the "Snakes of Singapore" Mobile Application, developed by Wildlife Reserves Singapore. |

Snake Identification tools, based on physical descriptions. |

List of highly venomous snakes, these require swift medical attention! |

4b. If the snake is not highly venomous, treat as a puncture wound . However, seek medical attention if local symptoms develop, as that may be indicative of secondary infection. This applies to bites by the mildly venomous Paradise Tree Snake.

5a. What to expect at the hospital: the wound may be inspected for active bleeding, swelling, and intensity of pain. Gentle irrigation and pain relief may be helpful. Monitoring of vital signs are also essential. Anti-venom may be administered if the situation is life threatening.

Are you field-ready?

Now that you’ve got some idea of this species, do you think you are field-ready? What would you do if you find yourself in such a scenario? |

1) You see a snake that wrapped itself around a branch just adjacent to the forest boardwalk. What physical characteristics would you look out for to confirm if it is the Paradise Tree Snake? 2) You see a snake gliding from approximately 10m horizontally and 20m above you, is possible for you to be in the trajectory of Paradise Tree Snake’s glide? 3) You meet a child with a wound from a snake bite on her palm. The child’s account of the snake seems to fit the Paradise Tree Snake. As the only adult present, what would you do? |

Highlight text on the right to reveal answers! |

1) What are the colours on the body- black body with greenish-yellow to reddish-orange spots, yellow underparts. Some of the spots on the head are arranged as horizontal bands. What is the size of the snake- body cross section slightly thicker than a normal pen, about 1m to 1.3m long. 2) Field observations show an average horizontal gliding distance of 10m from launch height of 9m. However, in the experiments done by Jake Socha (watch video above), snakes released at a height of 10m were recorded to glide for up to 21m. So be on high alert, the snake might come really close to you! 3) Calm the child down, keep his/her hand below his/her heart with minimal movement. Show the child a photograph of the snake to confirm if the snake was the Paradise Tree Snake. If certain, reassure the child and treat the wound like a puncture wound. This includes stopping the bleeding by adding firm direct pressure with sterile gauze or clean cloth, rinsing the wound, and wrapping with a sterile bandage to protect from dirt of further injury. DO NOT attempt first-aid measures like wiping the wound with damp cloth, in/excision, amputation, suction by mouth. If there are signs of infection (redness, increasing pain, swelling or pus present), seek medial attention. |

E. Nomenclature and Taxonomy

Past Species description

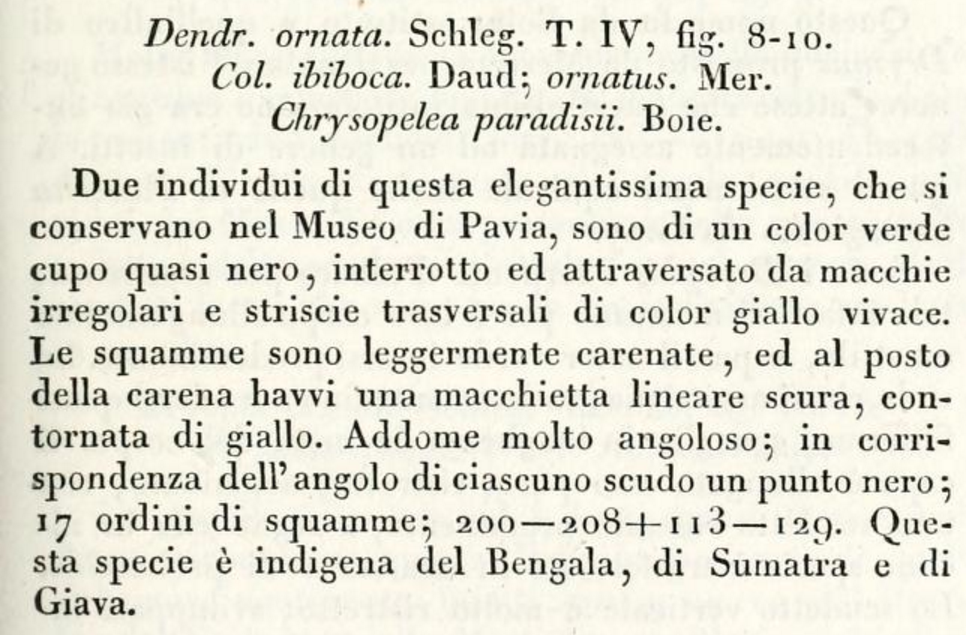

The original description of Chrysopelea paradisi by the species authority, H. Boie in F. Boie, 1827 could not be located. The next oldest journal article found offering a species description was in 1840. |

| Screen capture of the species description featured in Biblioteca Italiana (1840).[35] Available under CC BY-NC 3.0 |

Two individuals of this elegant species, which are preserved in Pavia museum, are of a dark green, almost black color, interrupted and traversed by irregular spots and transverse stripes of bright yellow color. The scales are slightly keeled, and instead of the hull have a dark speck linear, outlined in yellow. Very angular abdomen; in correspondence of each shield a black point; 17 rows of scales; 200-208 + 113-129. This species is native to Bengal, Sumatra and Java

Type Specimens

Species descriptions are made based on a type specimen, often identified at the time of the species discovery. Unfortunately, for the case of Chrysopelea paradisi, the holotype was believed to be lost according to Mertens.[36] A female individual (specimen code RMNH 885) found in Southwest Indonesia, Java, described by Boie and Macklot in 1826, was hence subsequently determined to be the neotype (name-bearing type specimen chosen by a later researcher) by Mertens in 1968.[37] The neotype is of the nominate subspecies Chrysopelea paradisi paradisi, the subspecies that was first described. Little else is know about the neotype. The other two subspecies were distinguished subsequently, with known holoytypes and paratypes of Chrysopelea paradisi celebensis from Celebes (Sulawesi),[38] and of Chrysopelea paradisi variabilis from Philippines.[39]Taxonomic Classification

To give a sense of the placement of the Paradise Tree Snake (Chrysopelea paradisi) in the larger scheme of organisms, this is the current classification it belongs to.[40] While the ranks may not be meaningful entities on their own, it informs us about the groupings within which smaller subsets can be made to distinguish more closely related species.| Rank |

Taxa |

| Kingdom |

Animalia |

| Phylum |

Chordata |

| Subphylum |

Vertebrata |

| Superclass |

Gnathostomata |

| Class |

Sarcopterygii |

| Order |

Squamata |

| Family |

Colubridae |

| Genus |

Chrysopelea |

| Species |

Chrysopelea paradisi |

| Subspecies |

C. paradisi paradisi, C. paradisi celebensis, C. paradisi variabilis |

Nomenclature & Etymology

(Naming of the species & the origin of the name)| Binomial Name |

Chrysopelea paradisi |

| Common Names |

Paradise Tree Snake, Paradise Gliding Snake, Paradise Flying Snake, Garden Flying Snake. |

Synonyms

When sourcing for information on the Paradise Tree Snake, these are some synonyms to consider.[42] Having multiple synonyms poses a problem such that information of particular individuals may be filed under names that are incorrect or no longer valid. This includes the grouping of the species with Chrysopelea ornata in the past and the various subspecies. Taxonomic names in bold remain valid for refering to the species and subspecies.| Chrysopelea paradisi— BOIE 1827 |

Chrysopelea paradisi paradisi — CHAN-ARD et al. 1999: 161 |

| Chrysopelea paradisi paradisi— BOIE 1827 |

Chrysopelea paradisi — WALLACH et al. 2014: 168 |

| Chrysopelea paradisi — H. BOIE in F. BOIE 1827 |

Chrysopelea paradise — JANIAWATI et al. 2016 (in error) |

| Chrysopelea paradisi paradisi — MERTENS 1968 |

Chrysopelea paradisi celebensis MERTENS, 1968 |

| Chrysopelea ornata — BOIE 1827 (nec Coluber ornatus SHAW 1802) |

Chrysopelea paradisi celebensis — DE LANG & VOGEL 2005 |

| Dendrophis ornata (partim) — SCHLEGEL 1837 |

Chrysopelea paradisi celebensis — ISKANDAR & ERDELEN 2006 |

| Leptophis ornatus var. (partim) — CANTOR 1847 |

Chrysopelea paradisi celebensis — WANGER et al. 2011 |

| Chrysopelea paradisi — SMITH 1943 |

Chrysopelea paradisi variabilis MERTENS 1968 |

| Chrysopelea paradisi — MANTHEY & GROSSMANN 1997: 333 |

Chrysopelea paradisi variabilis — GAULKE 2012 |

| Chrysopelea paradisi — COX et al. 1998: 67 |

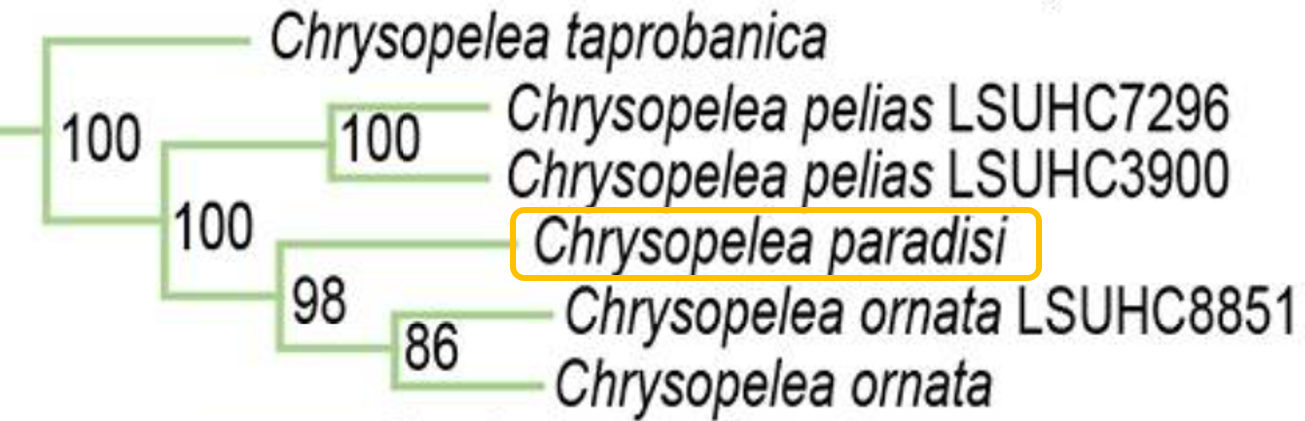

Chrysopelea paradisi was previously incorrectly listed in synonymy with Chrysopelea ornata, until revalidation of Chrysopelea paradisi at species level by Smith in 1943. Smith likely deemed them to be distinct species while applying the Phylogenetic Species Concept sensu Wheeler and Platnick, as he used the presence or absence of hypapophyses on the posterior dorsal vertebrae, which correlated with geographical distribution and colour pattern, to separate the species.[44] Reports of the Paradise Tree Snake up until 1943 may thus be filed under the name of Chrysopelea ornata, which is a probable problem given that there was some overlap in the geographic range of these two species.

Phylogenetics

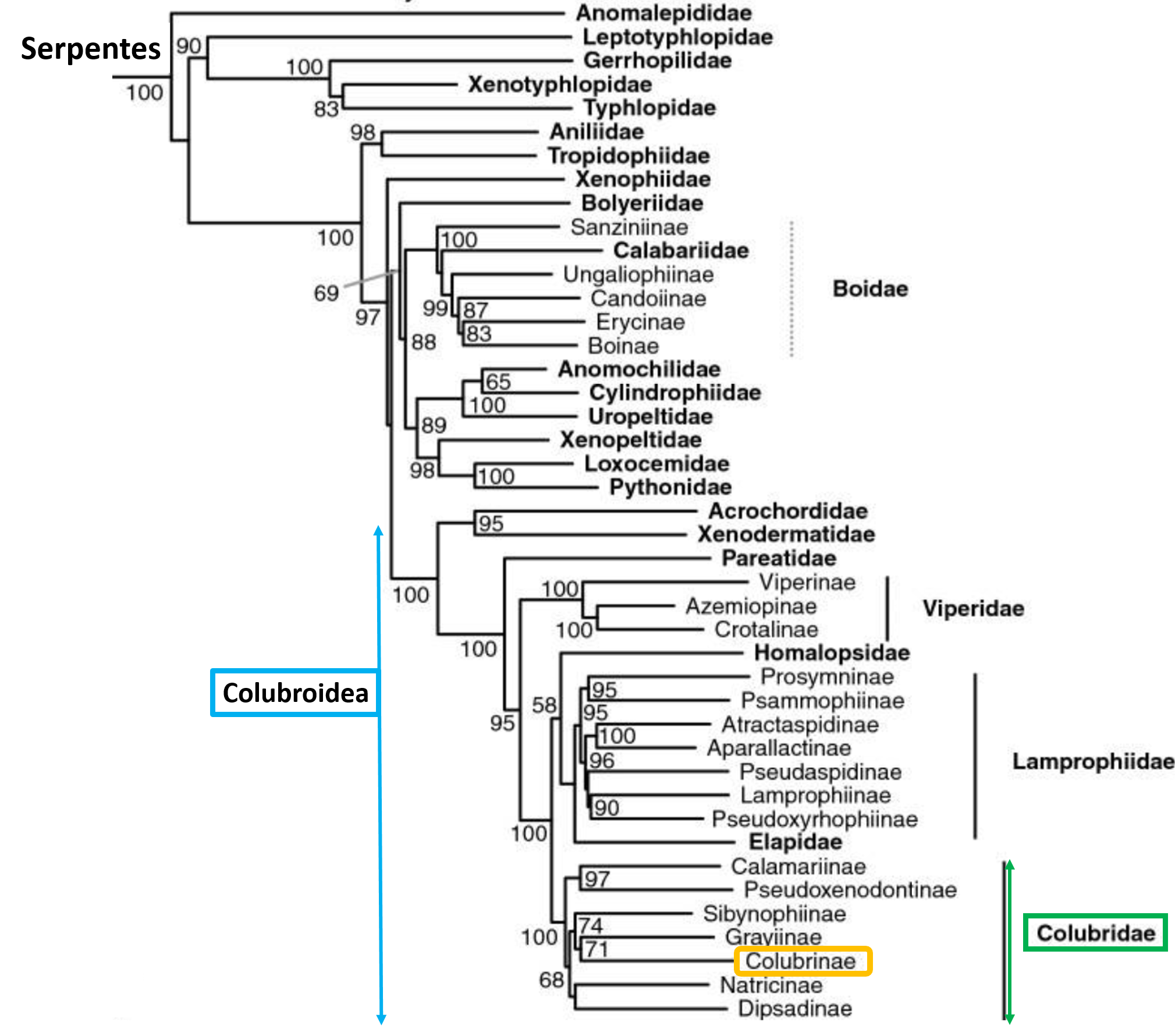

Snakes (suborder Serpentes) are classified under the order Squamata, together with lizards and amphisbaenians (worm-lizards). Serpentes are a well-defined group with monophyly supported by both morphological and molecular characteristics.[45] Within Serpentes, there is the superfamily Colubroidea, the advanced snakes (sensu Lawson et al., 2005) which has one of the most extensive radiation among extant terrestrial vertebrates despite their relative recent origin in the Cenozoic. Colubroidea are sister group to Acrochordidae. Spread across all continents except Antartica, the Colubroidea include many common groups (racers, king, milk snakes etc) and notably all venomous snake species known to be dangerous (cobras, vipers, rattlesnakes etc).[46]The Colubridae family is the most species-rich family within all of Serpentes. The old family Colubridae, a large group of advanced snakes (caenophidians) without front-fanged venom system, was demonstrated to be paraphyletic because Viperidae, Elapidae and Attractaspididae were nested within it. As such, the modern treatment that has been gaining consensus is to restrict the name Colubridae to a single monophyletic group, and elevate most of the subfamilies to a family rank.[47] This is shown in the skeletal representation below, where the modern Colubridae family is shown to be monophyletic. Colubridae is now sister group to the clade consisting of Elapidae, Lamprophiidae and Homalopsidae.

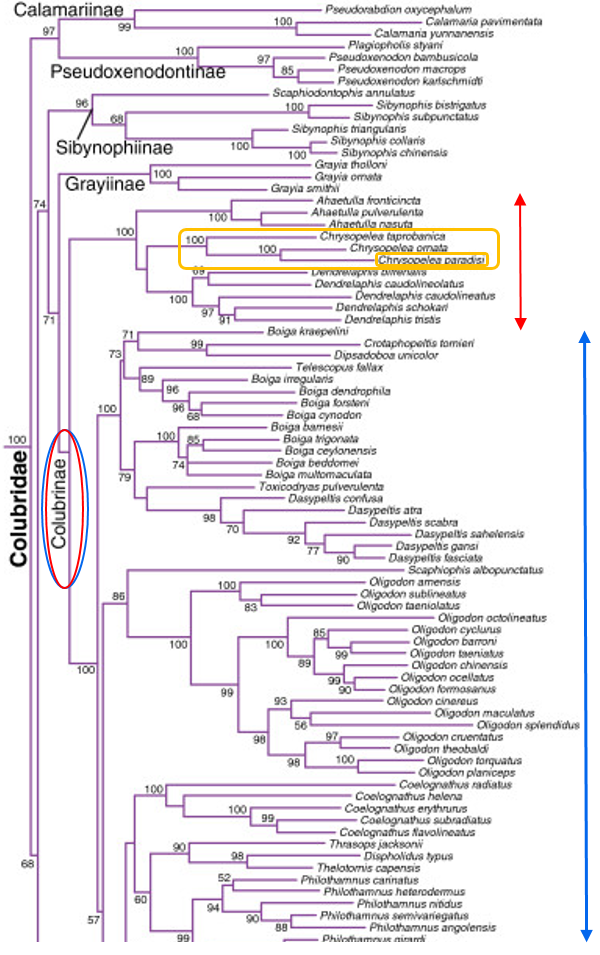

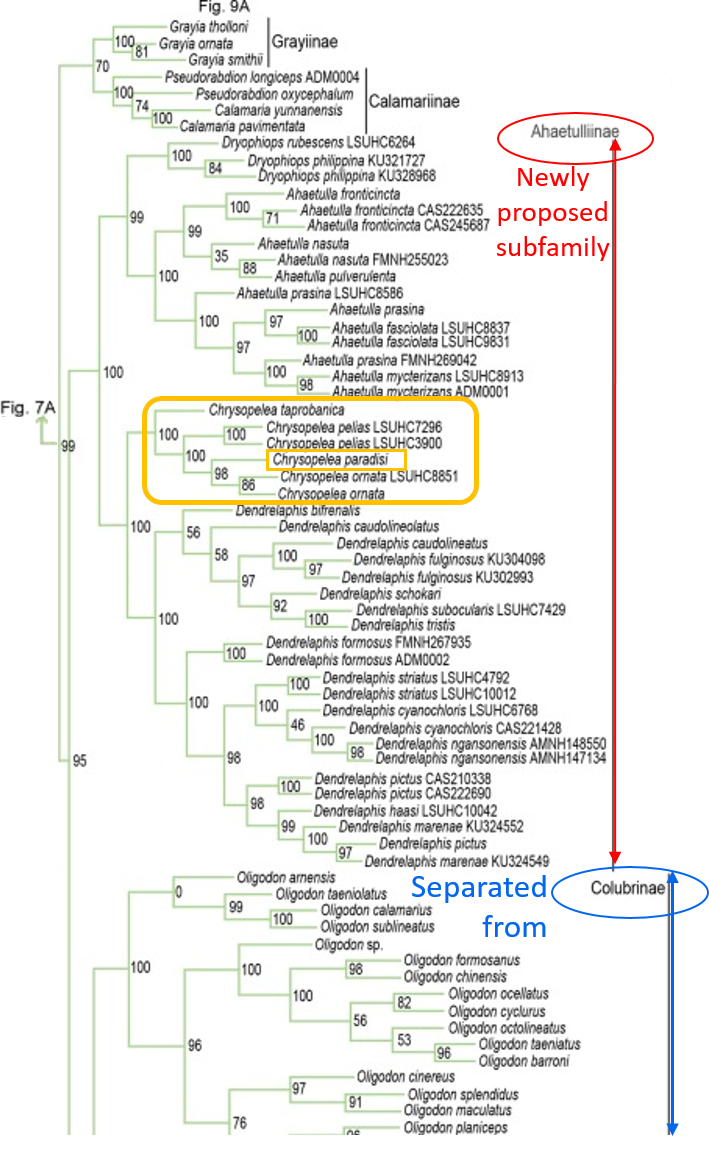

The family Colubridae contains more than 85% of extant snake species, and is grouped into many proposed subfamilies.[48] Although there is support for the monophyly of Colubridae, the relationships among the subfamilies are weakly supported.[49] The clade of Natricinae and Dipsadinae is weakly supported (SHL value 68, of which >85 indicates a well-supported node) as the sister group to a clade made up of Sibynophiinae, Colubrinae and Grayiinae. [50]

|

| Skeletal representation of the 4161-species tree from maximum-likelihood analysis of 12 genes, with tips representing families and subfamilies. Numbers at nodes are Shimodaira-Hasegawa-like [SHL] approximate likelihood ratio values, indicated if greater than 50. Image from Pyron et al. (2013), annotated by Lim Jia Ying. (Open access journal, also used with permission) |

|

|

| Maximum Likelihood phylogenetic estimate using 12-gene concatenated matrix. Node support values >85 are considered as strong support. Image from Pyron et al. (2013), annotated by Lim Jia Ying. (Open access journal, also used with permission) |

Maximum Likelihood phylogenetic estimate based on 10 concatenated genes, after running 1000 non-parametric bootstrap replicates. SHL values >85 are considered as strong support. Image from Figueroa et al. (2016), annotated by Lim Jia Ying. (Open access journal, also used with permission) |

|

| Image from Figueroa et al. (2016), annotated by Lim Jia Ying. (Open access journal, also used with permission) |

F. Useful links

For Singapore-specific resources:Singapore's Snake Blog (Documents snake sightings in Singapore)

Herpetological Society of Singapore (Documents herp sightings and offers free guided walks)

Handy emergency hotline and mobile applications:

AVA's Advisory on Snake (What to do when there's a snake indoors/ in urban areas)

Contact ACRES (24hour hotline to rescue and relocate wildlife)

'Snakes of Singapore' on iOS (Useful Mobile Application, free download)

'Snakes of Singapore' on Android (Useful Mobile Application, free download)

For more specific information:

Genbank records (DNA sequences for use in scientific research)

On captive individuals (with rare photographs of reproductive behaviour)

|

| Webpage done by: Lim Jia Ying (2016). Contactable at limjyjy55@gmail.com |

- ^ Baker, N., & Lim, K. K. P. (2012). Wild Animals of Singapore: A Photographic Guide to Mammals, Reptiles, Amphibians and Freshwater Fishes. Singapore: Draco Publishing and Distribution Pte Ltd and Nature Society (Singapore).

- ^ Baker, N., & Lim, K. K. P. (2012). Wild Animals of Singapore: A Photographic Guide to Mammals, Reptiles, Amphibians and Freshwater Fishes. Singapore: Draco Publishing and Distribution Pte Ltd and Nature Society (Singapore).

- ^ Kaiser, H., Lim, J., Worth, H., & O’Shea, M. (2016). Tangled skeins: a first report of non-captive mating behavior in the Southeast Asian Paradise Flying Snake (Reptilia: Squamata: Colubridae: Chrysopelea paradisi). Journal of Threatened Taxa, 8(2), 8488-8494.

- ^ Vogel, G., Wogan, G., Diesmos, A.C., Gonzalez, J.C. & Inger, R.F. (2014).Chrysopelea paradisi. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2014: e.T183189A1732041.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-1.RLTS.T183189A1732041.en Downloaded on 20 October 2016. - ^ Thomas, N., & Boopal, A. (2014). Golden gliding snake at Shenton Way. Singapore Biodiversity Records 2014, 51. Retrieved from https://lkcnhm.nus.edu.sg/nus/pdf/PUBLICATION/Singapore%20Biodiversity/2014/sbr2014-051.pdf

- ^ Maury, N. & Low, M-R. (2015). Golden gliding snake at Lim Chu Kang. Singapore Biodiversity Records 2015, 76. Retrieved from https://lkcnhm.nus.edu.sg/nus/images/pdfs/sbr/2015/sbr2015-076.pdf

- ^ Obelgönner, L. (n.d.) Reptile Care Database: Chrysopelea paradisi- Boie 1827. Retrieved from http://www.reptile-care.de/species/Serpentes/Colubridae/Chrysopelea-paradisi.html

- ^

Cox, M. J., van Dijk, P. P., Nabhitabhata, J. and Thirakhupt, K. (1998). A Photographic Guide to Snakes and Other Reptiles of Thailand and South-East Asia. Bangkok: Asia Books.

Baker, N., & Lim, K. K. P. (2012). Wild Animals of Singapore: A Photographic Guide to Mammals, Reptiles, Amphibians and Freshwater Fishes. Singapore: Draco Publishing and Distribution Pte Ltd and Nature Society (Singapore).

Vogel, G., Wogan, G., Diesmos, A.C., Gonzalez, J.C. & Inger, R.F. (2014).Chrysopelea paradisi. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2014: e.T183189A1732041.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-1.RLTS.T183189A1732041.en Downloaded on 20 October 2016.

ACRES: Animal Concerns Research and Education Society (Singapore). (2012). Pearly, a Paradise Tree snake, got herself extremely lost and was found at basement 1 at an Outram MRT. Retrieved from https://www.facebook.com/ACRESasia/photos/a.223077136522.136042.22159071522/10150713774826523/?type=3&theater

Socha, J. J., O’Dempsey, T., & LaBarbera, M. (2005). A 3-D kinematic analysis of gliding in a flying snake, Chrysopelea paradisi. Journal of Experimental Biology, 208, 1817-1833.

Dudley, R., & Yanoviak, S. (2011). Animal aloft: the origins of aerial behavior and flight. Integrative and Comparative Biology, 51, 926-936.

Socha, J. J. (2011). Gliding Flight in Chrysopelea: Turning a Snake into a Wing. Integrative and Comparative Biology, 51(6), 969-982.

Krishnan, A., Socha, J. J., Vlachos, P. P. & Barba, L. A. (2014). Lift and wakes of flying snakes. Fluid Dynamics, 26, 031901.

Tweedie, M. W. F. (1983). The Snakes of Malaya. Singapore: Singapore National Printers.

Tan, R. (2014). Paradise tree snake: Chrysopelea paradisi. Retrieved from http://www.wildsingapore.com/wildfacts/vertebrates/snakes/paradisi.htm

Stuebing, R.B. & Inger, R.F. (1999). A Field Guide to the Snakes of Borneo. Borneo: Natural History Publications.

Tan, R. (2014). Paradise tree snake: Chrysopelea paradisi. Retrieved from http://www.wildsingapore.com/wildfacts/vertebrates/snakes/paradisi.htm

Borke, J. (2015). Snake bites. Retrieved from https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/000031.htm

Wallach, V., Williams, K. L., & Boundy, J. (2014). Snakes of the World: A Catalogue of Living and Extinct Species. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

Wallach, V., Williams, K. L., & Boundy, J. (2014). Snakes of the World: A Catalogue of Living and Extinct Species. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

Myers, P., R. Espinosa, C. S. Parr, T. Jones, G. S. Hammond, & T. A. Dewey. (2016). The Animal Diversity Web (online). Retrieved from http://animaldiversity.org

Hallermann, J. (n.d.) Chrysopelea paradisi BOIE, 1827. Retrieved from http://reptile-database.reptarium.cz/species?genus=Chrysopelea&species=paradisi

Encyclopedia of Life. (n.d.). Chrysopelea paradisi: Paradise tree Snake. Retrieved from http://eol.org/pages/795382/names/synonyms

Alroy, J. (2005). How to read a synonymy list. Retrieved from http://paleodb.org/public/tips/taxonomy_tips.html

Leviton, A. E. (1964). Contributions to a review of Philippine snakes, IV: The genera Chrysopelea and Dryophiops. The Philippine Journal of Science, 98(1), 131-145.

Grant Museum of Zoology. (n.d.) Vertebrate diversity. Retrieved from http://www.ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/obl4he/vertebratediversity/serpentes_snakes.html

Quijada-Mascarenas, A. & Wuster, W. (2016). Recent Advances in Venomous Snake Systematics. In Mackessy, S. P. (Ed.), Handbook of Venoms and Toxins of Reptiles. Boca Raton: CRC Press (25-64).

Pough, F. H., Andrews, R. M., Cadle, J. E., Crump, M. L., Savitzky, A. H., & Wells, K. D. (1998). Herpetology. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

Pough, F. H., Andrews, R. M., Cadle, J. E., Crump, M. L., Savitzky, A. H., & Wells, K. D. (1998). Herpetology. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

Pyron, R. A., Kandambi, H. K. D., Hendry, C. R., Pushpamal, V., Burbrink, F. T., & Somaweera, R. (2013). Genus-level phylogeny of snakes reveals the origins of species richness in Sri Lanka. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 66(3), 969-978.