Chamaeleo chamaeleon (Linnaeus, 1758)

Table of Contents

The truth is, there are NO chameleons in our local lands! Lizards that can change color actually look really different from an actual chameleon and they should not be mistaken as one for the other.

Here is a picture of the Common Chamaeleon:

|

| Chamaeleo chamaeleon (Photo taken from Flickr; Permission granted) |

One of the most commonly misidentified smaller lizards of the wild is the Changeable Lizard / Oriental Garden Lizard, Calotes versicolor. Yes, they do change color for camouflaging purposes, but they are NOT chameleons. In Singapore, they can be found near mangroves and coastal vegetation.[1]

|

| Changeable Lizard (Calotes versicolor). Source: Wild Singapore (2016) |

Another lizard commonly mistaken for a chameleon is the Green crested lizard, Bronchocela cristatella. This lizard used to be commonly found among bushes and trees in forested areas, but has became displaced by the former. [2]

|

| Green crested lizard, Bronchocela cristatella. Source: WildSingapore (2016) |

For a better idea of what true chameleons are really all about, here is a brief introductory video on Chamaeleo Chamaeleon!

1. Diagnosis

1.1 Morphology

Chamaeleo chamaeleon has an arched body which is compressed laterally. Generally, it has two light stripes along the sides of its body, which are often being broken into a series of dashes or spots [3] .The limbs are long and slender, its prehensile tail of equal or shorter length than the rest of the body. Chamaeleo chamaeleon has a variable background color that is capable of changing. These traits make this species distinctive and well-known to all [10] .The head of Chamaeleo chamaeleon is distinct from its body; it is pointed with two occipital lobes on the crest of each side. Along its throat is a light crest of scales, and along its back is a crest of small, serrated scales

[3] . The eyes are prominent, having circular eyelids and located on each side of the head. It has small nostrils and no external ear [10] .

Size: Snout-vent length: 8.5 - 16 cm [4]

Weight: about 35 g [15]

| Anatomy of the Common Chamaeleon, annotated by Li Min. Image taken from Flickr (permission granted) |

1.2 Characteristics

Like all chameleons, Chamaeleo chamaeleon has a long, sticky tongue which can be twice the length of the body when extended.Its strong feet to hold firmly to branches, and prehensile tail, enables it to be well adapted to living in bushes and trees [15] .

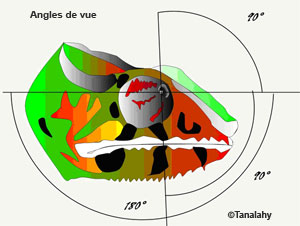

Chameleons have very sharp eyesight but unlike popular beliefs, chameleons does not have 360 degrees vision, though almost. This ability is due to each eyeball being able to move independently of the other with a high degree of freedom, allowing it to have stereoscopic vision (180 degrees horizontally and +/-90 degrees vertically) [5] . Also, chameleons have the ability to transition between monocular and binocular vision, which means they have the option to view objects with either eye independently, or with both eyes together. The ability to transition enables chameleons to have panoramic vision (wide and extensive view in all directions).

|

| Angles of view for chameleon's eye. Source: Biomimicry Institute (2017) |

1.3 Juveniles

The juveniles are similar in appearance and coloration to adults, but unlike adults, their heads are rounded and have a black palate, especially newborns [10] .1.4 Sexual Dimorphism

Generally dominant males have a bright green, while muted tones prevail in less dominant males [2] .During mating season, females may display yellow, orange or green spots [6] and are generally slightly heavier than the males [15] . Fertilized females then take on a dark blue color stained yellow.

At night, common chameleons are typically neutral tones while they sleep [2] .

2. Biogeography

2.1 Distribution

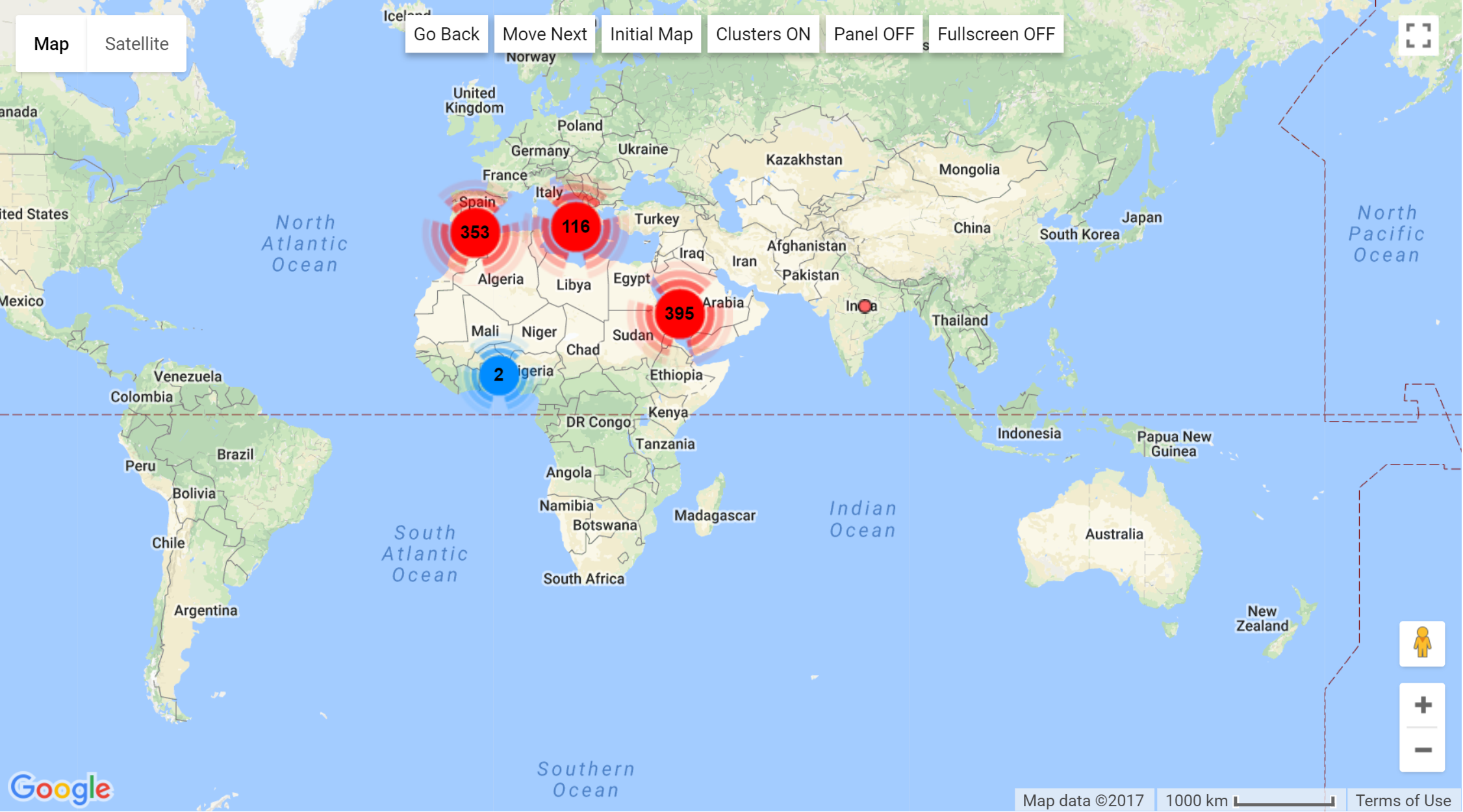

Chamaeleo chamaeleon’s range is the broadest out of all chameleon species [7], extending from northern Africa to southwest Asia and southern Europe [16] [7] [22] . It has been introduced to parts of Italy, Portugal, Spain and the Canary Islands [16] [22] even though this species is not native to those places.

|

| Estimated numbers of Chamaeleo chamaeleon. Source: Encyclopedia of Life (2017) |

2.2 Habitat

The Common chameleon can be found in a variety of habitats, including open pine woodland, shrubland, plantations, gardens and orchards [16] . The majority of its time is spent in trees or bushes, as it prefers dense cover for camouflage [13] [17] . However, this behaviour changes during the mating season. Males have to descend to the ground to find a mate and females have to move to a lower level of vegetation [13] .The habitat use of different age groups of Common chameleons have been found to bear differences, with juveniles occupying low grasses instead of bushes and trees [15] .

|

| Chamaeleo chamaeleon high up in the trees. Source: Wikimedia Commons (2008) |

|

| Adult male Chamaeleo chamaeleon on ground. Source: Wikimedia Commons (2009) |

3. Biology

3.1 Lifespan

On average, Chamaeleo chamaeleon has a lifespan of approximately 3.6 years, in captivity [8] . Lifespan in the wild are not documented, nonetheless, chameleons in captivity generally have longer lifespans than the ones in the wild. Additionally, male chameleons tend to live longer than females. [9]3.2 Feeding Habits

The Common chameleon is active during the day [16] [16] . Its diet consists mainly of arthropods (grasshoppers, flies, bees, wasps, and ants) [13] , but has also been known to consume some fruit [16] . The Common chameleon is a slow-moving ‘sit-and-wait’ predator, it captures prey with its long, sticky tongue when prey comes within reach [16] [13] . The tongue is retracted into a bag like cavity in the bottom of the mouth and can be projected with great precision and breathtaking speed for a distance as long as the total length of the individual [10] .Strangely, adults tend to eat juveniles; As a result, when encountering an adult the young chameleons will flee or attempt to hide themselves [16]

Click here to view the tongue in action!

| (Upper left drawing) Sketch of chameleon projected tongue.(Lower left drawing) Structure of chameleon's tongue(Right) Launch of the tongue in three successive moments.Source: cdn.iopscience.com |

The incredible speed and accuracy of the ballistic tongue projection have induced studies to find out just how fast and how far it is.

Needless to say. the speed of a chameleon's tongue during prey capture is astonishingly fast; the chameleon lashes out its tongue at a speed of 0 to 60 miles per hour, within a hundredth of a second [11] . The rate actually defies the general principles of muscle power production, as the power is beyond what the tiny creatures can carry. The secret lies in the tongue's structure, consisting of unique elastic collagen structures which the chameleon releases like a catapult.

As for distance, the average chameleon can "shoot" its tongue out at more than 26 body-lengths per second (about 13.4 mph).

3.3 Reproduction

Similar among Chamaeleo species, both male and female Common chameleons become sexually mature within one year.The Common chameleon undergoes mating during late summer [12] , from around July to September [15] [6] [13] During this period, males will become aggressive and fight over a female or to protect their territory [4] . Larger females would induce more intense guarding and fighting among the males, as they tend to produce more eggs and hence are preferred [14] . The females produce between 5 and 45 eggs per clutch per year. From late summer to early autumn, females would descend to the ground to bury their eggs in soil [13] , incubating them for 10 to 12 months [16] [15] [17] . The newly hatched chameleons appears the following year, from August to November [6] [14] .

|

| Adult female Chamaeleo chamaeleon. Source: Flickr (2010) |

4. Color Changing

Chamaeleo chamaeleon is able to display a variation of colors, from bright green to dull brown [4] , tan or grey [3] , with a remarkable ability to change colors.The Common chameleon is preyed upon by domestic cats and snakes. During encounters with a predator, the chameleon responds by either freezing in its position, displaying an aggressive defence posture, fleeing quickly for cover or dropping to the ground to escape [4] . It may also attempt to camouflage itself to mimic the colour of its surroundings [15]

|

| Chamaeleo chamaeleon displaying black coloration due to fright. Source: Wikimedia Commons (2005) |

Lastly, this species may change its color to help regulate its temperature [15] .

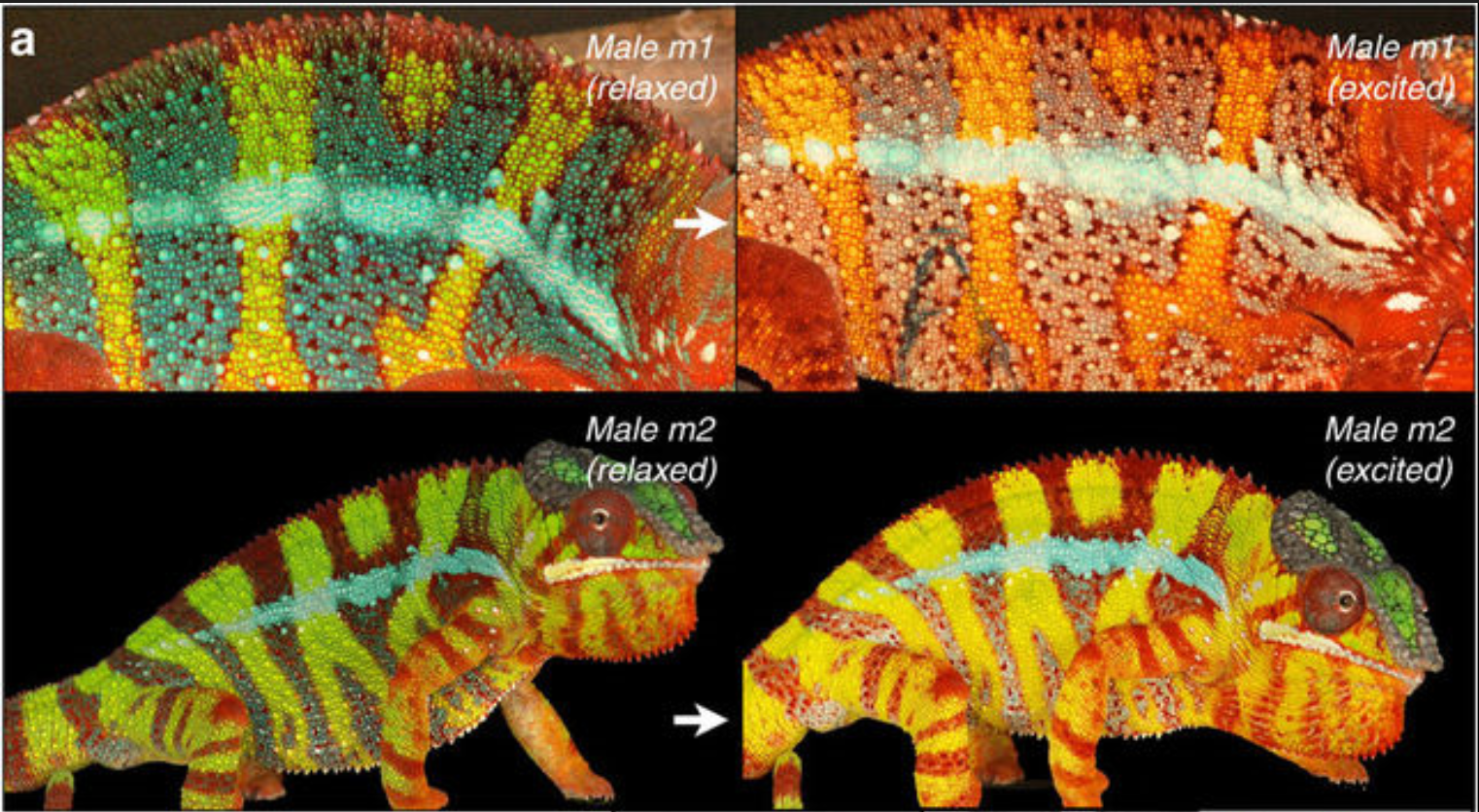

However, there is often a misconception on the chameleon's ability to change colors. For many years scientists have thought chameleons modify their colors by accumulating or dispersing pigments within skin cells. Recently, it was discovered that chameleons have two superposed thick layers of iridophore cells, which are iridescent cells that have pigment and reflect different wavelengths of light by adjusting their structure. The iridophore cells consist of nanocrystals, and when the chameleon relaxes or excites the skin it induces a change in structural arrangement of upper cell layers, hence color change.

When the skin is relaxed, the nanocrystals in the iridophore cells are very close to each other, hence the cells reflect short wavelengths, such as blue. When the skin is excited, neighboring nanocrystals become further apart, and each iridophore cell reflects longer wavelengths, such as yellow, orange or red. Nonetheless, the skin also contains yellow pigments, and when relaxed the blue mixes with yellow to form a greenish "cryptic" color that camouflages them among trees and plants.

|

| Reversible colour change is shown for two males (m1 and m2): during excitation (white arrows), background skin shifts from the baseline state (green) to yellow/orange and both vertical bars and horizontal mid-body stripe shift from blue to whitish (m1). Some animals (m2) have their blue vertical bars covered by red pigment cells.Source: Teyssier. J et. al (2015) |

The video explains this mechanism in greater detail.

5. Conservation

5.1 Status

On the IUCN Red List, Chamaeleo chamaeleon is classified as Least Concern (LC) [16] , and on Appendix II of CITES [18] . |

| Source: IUCN Red List (2017) |

Even though Chamaeleo chamaeleon is currently not considered to be at risk of extinction, it still faces threats such as forest fires, accidental deaths on roads, predation, and nest loss due to ploughing [15] [16] . It also experienced habitat loss from the expansion of urban areas, farming land and tourist facilities [17] . Furthermore, this species is also captured for the international pet market, sometimes illegally [16] .

5.3 Conservation Efforts

Various measures have been implemented in some countries to help conserve the Common chameleon. In Spain, barriers are set up on several roads to prevent road kills. Protected areas also includes parts of this species' range [16] .Additionally, being listed on Appendix II of Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) means that there is careful control on any international trade in this species [17] . It also receives protection under Annex II of the Bern Convention, aiming to conserve the species and its habitat [18] .

Recommended future conservation measures for Chamaeleo chamaeleon include controlling usage of insecticides that can kill or reduce its insect prey, and providing nesting sites by protecting certain cultivated areas.

6. Taxonomy and Systematics

The genus Chamaeleo is a type genus of family Chamaeleonidae, which used to consist of the subfamily Chamaeleoninae (genus Bradypodion, Calumma, Furcifer, Kinyongia, Nadzikambia and Trioceros) but are now separate [19] .Made up of 14 species (excluding subspecies) globally [20] , these chameleons are found primarily in mainland of sub-saharan Africa, with a few species also present in Southern Europe, Northern Africa, and Southern Asia east to Sri Lanka and India [2] .

Chameleons are mostly arboreal, typically found in trees and / or bushes, with a few exceptions (i.e. Namaqua Chameleon, Chamaeleo namaquensis) being partially or largely terrestrial. All species in the genus are oviparous.

Binomial: Chamaeleo chamaeleon

Vernacular: Common chameleon, Mediterranean chameleon

6.1 Synonyms

Lacerta chamaeleon LINNAEUS 1758: 204Chamaeleo parisiensium LAURENTI 1768

Chamaeleon vulgaris - DAUDIN 1802

Chamaeleo carinatus - MERREM 1820 (n. subst. pro Ch. parisiensium)

Cameleo siculus GROHMANN 1832

Chamaeleo Vulgaris — DUMÉRIL & BIBRON 1836: 204

Chameleon parisiensis - GRAY 1845 (n. subst. pro Ch. parisiensium)

Chamaeleo vulgaris — TURNER 1853: 292

Chameleo Vulgaris — DUMÉRIL, BIBRON & DUMÉRIL 1854: 245

Chamaeleo cinereus STRAUCH 1862 (BOETTGER 1874 fide SCHLEICH et al.)

Chamaeleon vulgaris — GRAY 1865: 344

Chamaeleon auratus GRAY 1865 (syn. Ch. chamaeleon orientalis)

Chameleon parisientium - BOSCA 1880 (err. pro Chamaeleo parisiensium)

Chamaeleon fasciatus SMITH 1866

Chamaeleo vulgaris — BOETTGER 1885: 472

Chamaeleo saharicus MÜLLER 1887

Chamaeleon chamaeleon saharicus — WERNER 1911: 10

Chamaeleo chamaeleon — ENGELMANN et al 1993

Chamaeleo chamaeleon — SCHLEICH, KÄSTLE & KABISCH 1996: 312

Chamaeleo (Chamaeleo) chamaeleon — NECAS 1999: 120

Chamaeleo chamaeleon — TILBURY & TOLLEY 2009

Chamaeleo chamaeleon — TILBURY 2010: 467

Chameleo chameleon — FOUDA & EL MANSI 2017 (in error)

Chamaeleo (Chamaeleo) chamaeleon chamaeleon (LINNAEUS 1758)

Chamaeleon hispanicus - FITZINGER 1843 (n. nud.)

Chamaeleon rimulosus GRAVENHORST 1843 (n. nud.)

Chamaeleon chamaeleon chamaeleon — WERNER 1911: 10

Chamaeleo (Chamaeleo) chamaeleon musae STEINDACHNER, 1901

Chamaeleo vulgaris var. musae STEINDACHNER 1901: 331

Chamaeleon chamaeleon musae — WERNER 1911: 10

Chamaeleon chamaeleon musae — IBRAHIM 2013

Chamaeleo chamaeleon orientalis PARKER 1938

Chamaeleo chamaeleon orientalis — SINDACO et al. 2014

Chamaeleo chamaeleon recticrista BOETTGER, 1880

Chamaeleo vulgaris var. recticrista BOETTGER 1880

Chamaeleo chamaeleon recticrista — ESTERBAUER 1985

Chamaeleo chamaeleon recticrista — HRAOUI-BLOQUET et al. 2002

6.2 Subspecies

Chamaeleo chamaeleon (Linnaeus, 1758) – common chameleon- Chamaeleo chamaeleon chamaeleon (Linnaeus, 1758) – European common chameleon

- Chamaeleo chamaeleon musae Steindachner, 1900 – Sinai Peninsula common chameleon

- Chamaeleo chamaeleon orientalis Parker, 1938 – Arabian common chameleon

- Chamaeleo chamaeleon rectricrista Boettger, 1880 – Middle East common chameleon

6.3 Specimens and Type locality

Syntypes: NRM (2 specimens; fide Andersson 1900: 13) [21] [1]Holotype: NHMB [saharicus]

Type locality: Africa, Asia [22]

6.4 Taxonomic Hierarchy

| Source: ITIS (2017) |

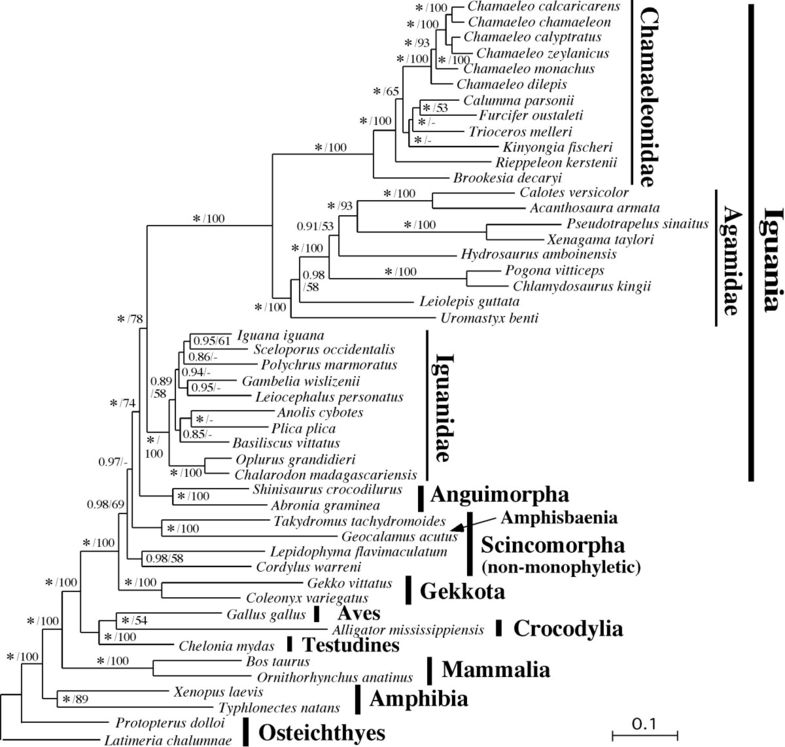

6.5 Bayesian Tree

|

| A Bayesian tree reconstructed using mitogenomic nucleotide sequences. Values to the left and right of slashes are Bayes-PP and ML bootstrap values (only for those larger than 50%), respectively. An asterisk for the posterior probabilities stands for 1.00.Source: Okajima & Kumazawa (2010) |

The tree illustrates how Infra Order Igunanidae has diverged into Agamidae (lizards) and Chamaeleonidae (chameleons). This classification is based on morphology (chameleons have unique morphologies as discussed above, setting them apart from Agamids) and molecular studies.

6.6 Molecular Studies

Phylogenetic relationships of iguanian lizards still requires elucidation, in spite of a number of morphological and molecular studies [23] . To address this issue, complete mitochondrial genomes from species representing major lineages of acrodont lizards have been sequenced.Results suggested independent gene rearrangement in both agamine and chamaeleonid lineages, with chamaeleonid being less related to Iguanidae. The control regions of chamaeleonid mitogenomes were found to be significantly longer than agamid and iguanid counterparts [20] .

7. References

- ^ WildSingapore (2016) Changeable lizard, Calotes versicolor. Retrieved from http://www.wildsingapore.com/wildfacts/vertebrates/reptilia/versicolor.htm (accessed 1 December 2017)

- ^

WildSingapore (2016) Green crested lizard, Bronchocela cristatella. Retrieved from http://www.wildsingapore.com/wildfacts/vertebrates/reptilia/cristatella.htm (accessed 1 December 2017)

Bartlett, R.D. and Bartlett, P.P. (1995) Chameleons: Everything about Selection, Care, Nutrition, Diseases, Breeding, and Behavior. Barron’s Educational Series, Inc., New York.

Cuadrado, M., Martín, J. and López, P. (2001) Camouflage and escape decisions in the common chameleon Chamaeleo chamaeleon. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 72: 547-554.

Biomimicry Institute (2017) Eyes give 360° vision - Chameleon. Retrieved from https://asknature.org/strategy/eyes-give-360-vision/#.WfbFF2iCw2w (accessed 30 October 2017).

Cuadrado, M. (1998a) The use of yellow spot colors as a sexual receptivity signal in females of Chamaeleo chamaeleon. Herpetologica, 54(3): 395-402

Dimaki, M., Valakos, E.D. and Legakis, A. (2000) Variation in body temperatures of the African chameleon Chamaeleo africanus Laurenti, 1768 and the common chameleon Chamaeleo chamaeleon(Linnaeus, 1758). Belgian Journal of Zoology, 130: 87-91

Human Ageing Genomic Resources (HAGR) (2017) AnAge entry for Chamaeleo chamaeleon. Retrieved from http://genomics.senescence.info/species/entry.php?species=Chamaeleo_chamaeleon(accessed 30 October 2017)

González de la Vega (2012) Common Chameleon Chamaeleo chamaeleon (Linnaeus, 1758). Retrieved from http://www.moroccoherps.com/en/ficha/Chamaeleo_chamaeleon/ (accessed 28 October 2017)

Orenstein-Brown. D, (2014) Speed test proves chameleon’s tongue is ridiculously fast. Retrieved from http://www.futurity.org/chameleon-tongue-speed-1083272/ (accessed 30 October 2017).

Pleguezuelos, J.M., Poveda, J.C., Monterrubio, R. and Ontiveros, D. (1999) Feeding habits of the common chameleon, Chamaeleo chamaeleon (Linnaeus, 1758) in the southeastern Iberian Peninsula. Israel Journal of Zoology, 45: 267-276.

Keren-Rotem, T., Bouskila, A. and Geffen, E. (2006) Ontogenetic habitat shift and risk of cannibalism in the common chameleon (Chamaeleo chamaeleon). Behavioural Ecology and Sociobiology, 59: 723-731

IUCN Red List (2012) Chamaeleo chamaeleon. Retrieved from http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/links/157246/0 (accessed 28 October 2017)

CITES (2017) Chamaeleo chamaeleon. Retrieved from https://cites.org/eng/node/20577 (accessed 28 October 2017

Glaw (2015) Taxonomic checklist of chameleons (Squamata: Chamaeleonidae). Vertebrate Zoology. SENCKENBERG, 65(2): 167 - 246

iNaturalist (2017) Common Chameleon (Chamaeleo chamaeleon). Retrieved from https://www.inaturalist.org/taxa/32864-Chamaeleo-chamaeleon (accessed 30 October 2017)

Andersson, L.G. 1900. Catalogue of Linnean type-specimens of Linnaeus's Reptilia in the Royal Museum in Stockholm. Bihang till Konglika Svenska Vetenskaps-Akademiens. Handlingar. Stockholm, (4) 26 (1): 1-29

The Reptile Database (2017) Chamaeleo chamaeleon (LINNAEUS, 1758). Retrieved from http://reptile-database.reptarium.cz/species?genus=Chamaeleo&species=chamaeleon (accessed 25 October 2017)

Okijima & Kumazawa (2010) Mitochondrial genomes of acrodont lizards: timing of gene rearrangements and phylogenetic and biogeographic implications. BMC Evolutionary Biology, 10:141.