Asian Fairy-bluebird, Irena puella (Latham, 1790)

The Asian fairy-bluebird is a beautiful passerine (songbird), and is found across tropical southern Asia, Indochina, the Greater Sundas and Palawan.[1] While not as commonly seen in Singapore, their charming bird call and exquisite plumage is sure to capture your attention.

|

| Photo credit: Francis Yap [Permission Granted] |

Table of Contents

1. A Fairy Tale about a Fairy Bluebird

|

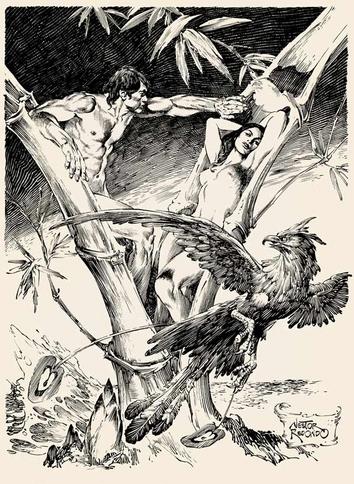

| Artist's rendition of the Tigamamanukan [CreativeCommons] |

Before delving into the biology and phylogeny of the Asian Fairy-bluebird, let us take a look at a Philippine mythology where it appears. Referred to as the Tigmamanukan, it was believed by the Tagalog people to be an omen bird. They would observe the direction of this bird’s flight at the beginning of a journey which supposedly foretold the success or failure of one’s quest. If it flew from right to left, success would be guaranteed, but if the bird flew from left to right, it meant never being able to come home again.[2]

If you decide to explore the Central Catchment Nature Reserve one day, observe its direction of its flight. Don’t worry though, Google maps and kind volunteers will help you find your way out!

2. Morphology

2.1 General description

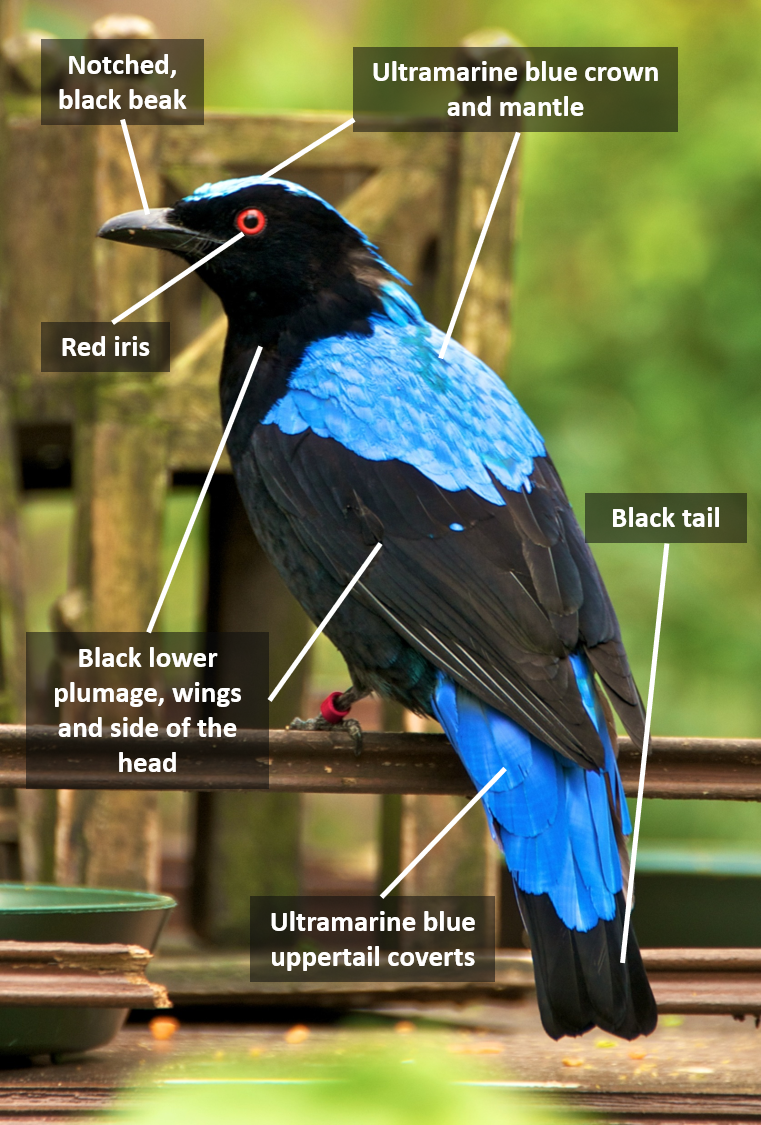

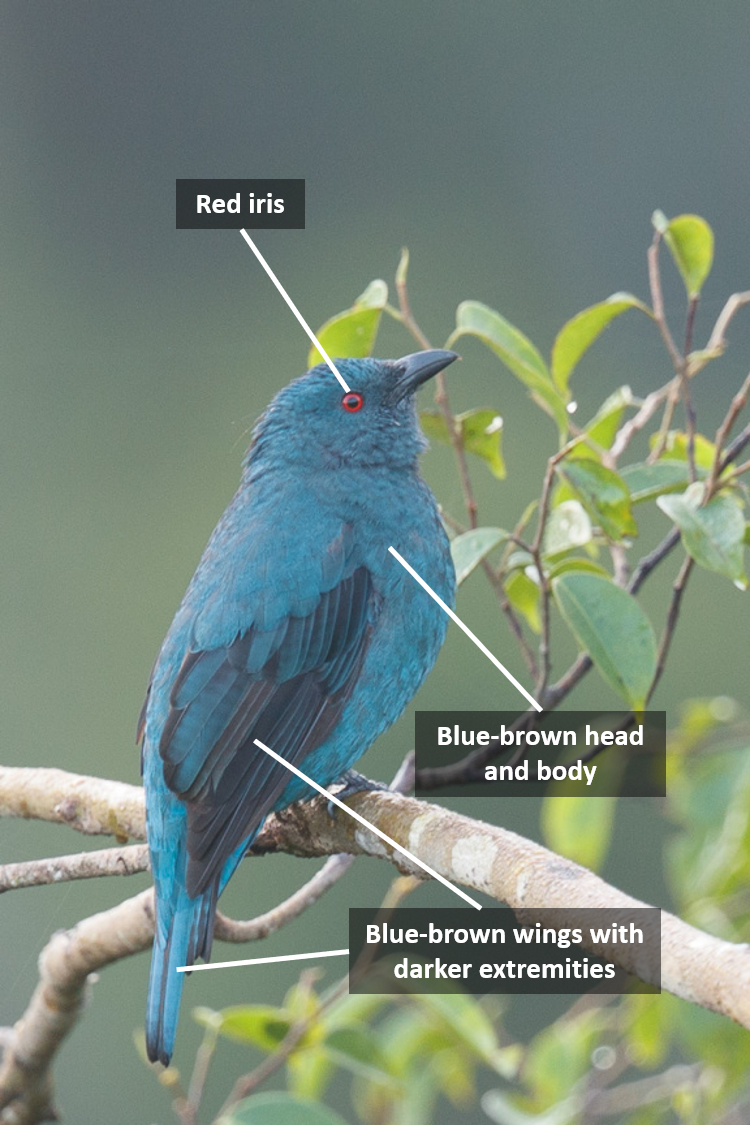

The Asian Fairy-bluebird shows very distinct sexual dimorphism. An adult can measure from 24 to 26 centimetres from beak to tail.[3] The male has an ultramarine, iridescent crown, mantle and upper tail coverts and covered by glossy black plumage in other places.[4] Females and first year males are, are however, of a dull, blue-brown colour. [5] Their toes and bills are black.[6] |

| Labelled diagram of a male Asian Fairy-bluebird Photo credit: Francis Yap [CreativeCommons] |

|

| Labelled photo of a female Asian Fairy-bluebird Photo credit: Francis Yap [permission granted] |

|

| Hatchling showing coloration similar to the females Photo credit: Victor Spaan [permission pending] |

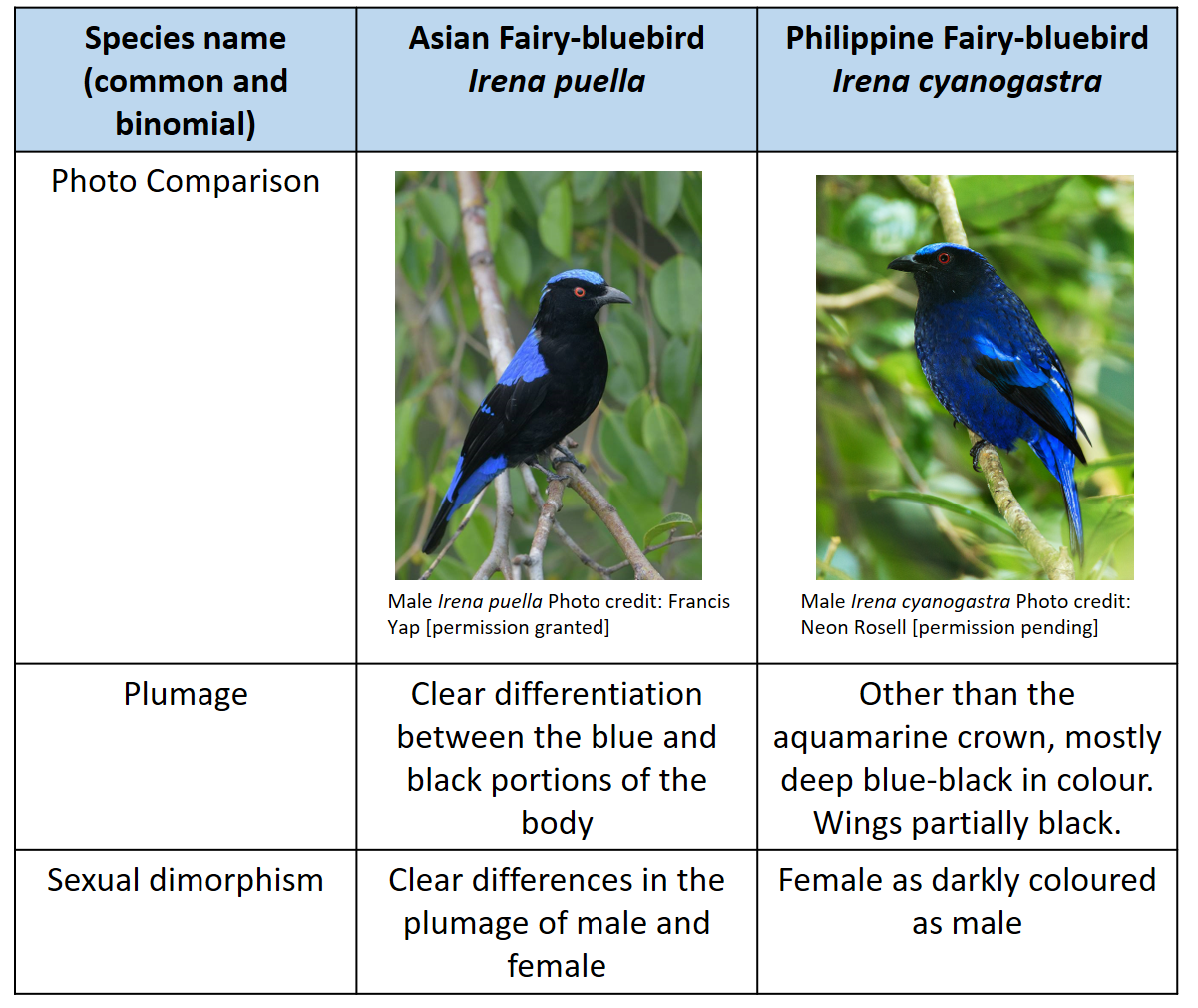

2.2 Comparison between two species of genus Irena

The family Irena consists of only two species, namely the Irena puella (Asian Fairy-bluebird) and Irena cyanogastra (Philippine Fairy-bluebird).[7] The latter is only found in the Philippines and cannot be observed in Singapore. The differences in their morphology is compared in the table below.

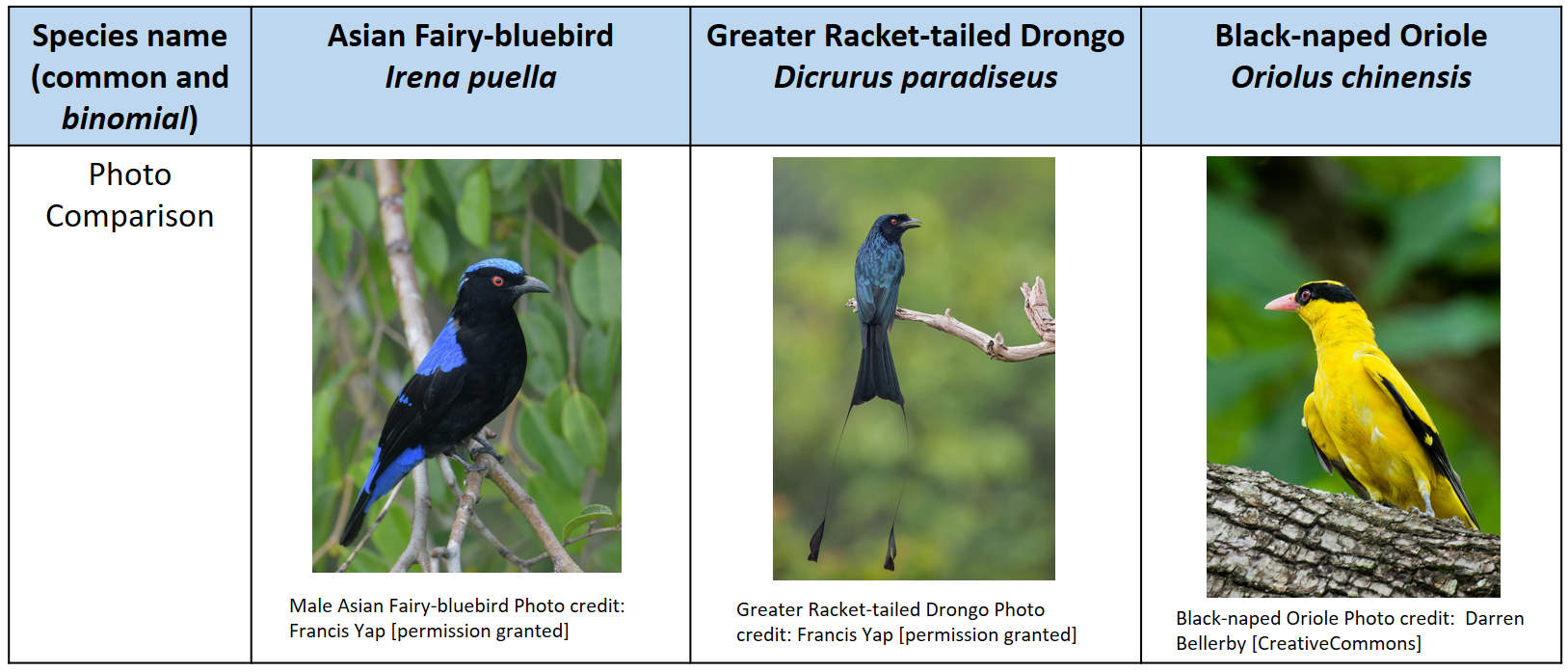

2.3 Comparison between species of similar morphology in the Central Catchment Nature Reserve

The Asian Fairy-bluebird shares a similar body form, red iris and beak shape with the Greater Racket-tailed Drongo (Dircrurus paradiseus) and the Black-naped Oriole (Oriolus chinensis). However, take a careful look at their plumages and tails. The Drongo has an obvious 'rackets' extending from the tail, while the Oriole is a beautiful shade of yellow, excluding its extremities and around its eyes.

3. Distribution and Range

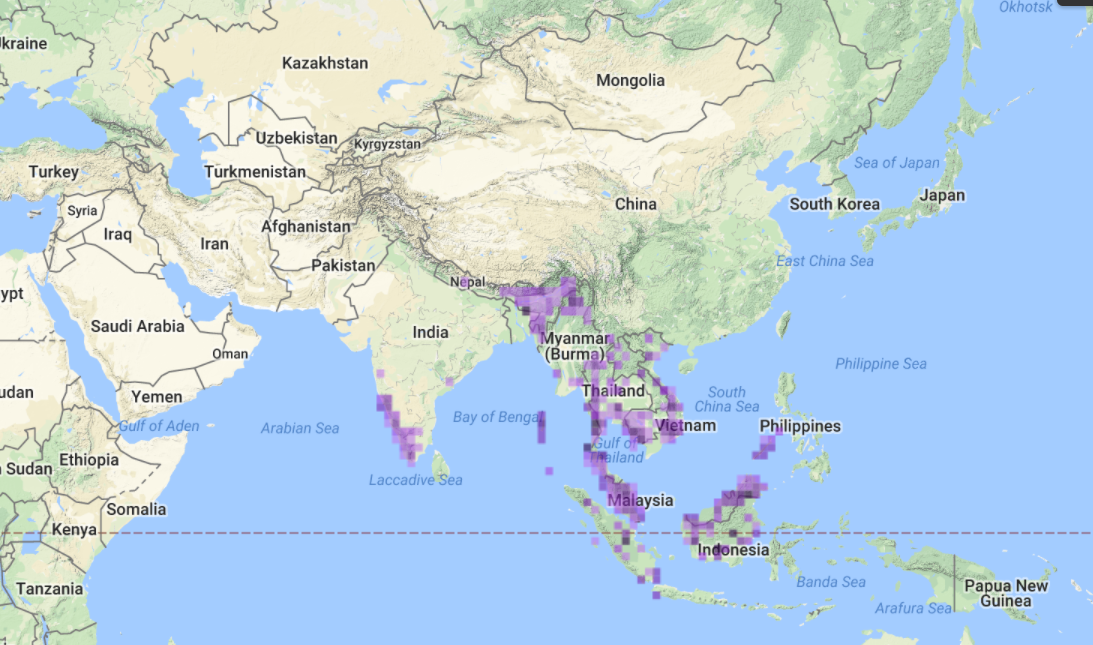

|

| Global distribution and range of the Asian Fairy-bluebird. Photo credit: eBird [fair use] |

In Singapore, these birds are confined to the Bukit Timah Nature Reserve and the Central Catchment Nature Reserve. [9]

4. Behaviour

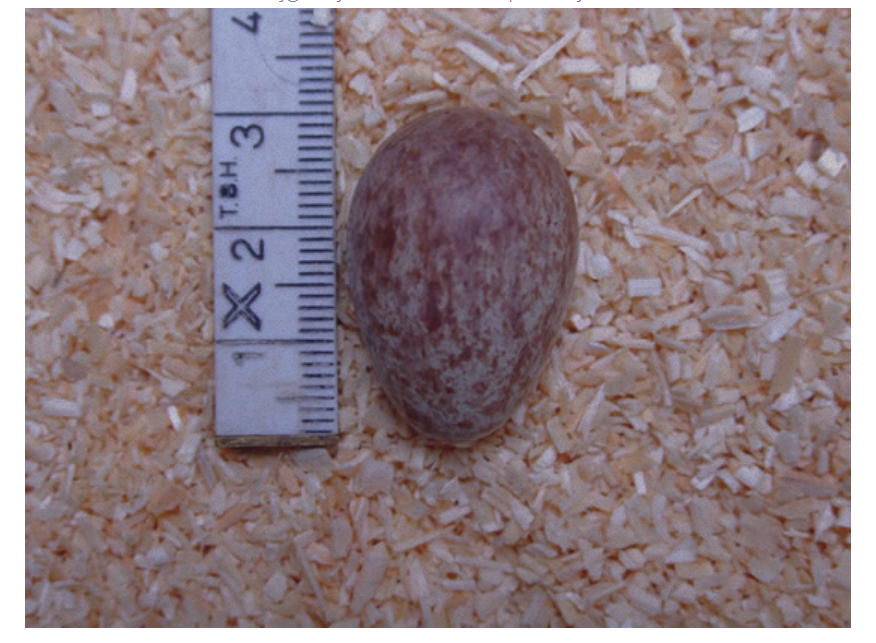

4.1 Eggs and nestingThe Asian Fairy-bluebird breeds from December to August. The nests are a shallow cup shape, made up of twigs and padded with mosses. The egg is an elongate oval, with a glossy shell that has brown patches. [10] 2 or 3 eggs are laid and incubated by the female, while the male aids in feeding the newly-hatched. [11]

|

| The egg of the Asian Fairy BluebirdPhoto credit: Victor Spaan [permission pending] |

4.2 Feeding

The Asian Fairy-bleubird is mainly a frugivore, and most often obtains its food from Common Mahang (Macaranga bancana) and the Weeping Fig (Ficus benjamina), but feeds on insects occasionally.[12] They are also commonly seen snatching fruits off the trees while in flight. [13] If you are hoping to catch a glimpse of this magnificent creature while visiting the CCNR, take a close look at the canopies of fig trees, where they can be found in small feeding groups.[14]

4.3 Calls

The calls are a piping sound ‘pee-dit’, which is often liquid and rises in tone. [15]

5. Status and Conservation

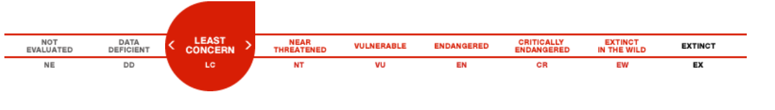

|

| Reflection of conservation status by IUCN: listed under ‘least concern’ categoryPhoto credit: IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (Free use) |

5.1 Regional

IUCN states that Irena puella is under ‘least concern’, and this is attributed to their large distribution around Southeast Asia and South Asia. [16] A species that is under the ‘vulnerable’ category is only when a species ‘Extent of Occurrence <20,000 km2 combined with a declining or fluctuating range size, habitat extent/quality, or population size and a small number of locations or severe fragmentation’. [17] This does not apply to the Asian Fairy Bluebird because its range is wide.[18] However, IUCN believes that the decrease in the number of individuals is fast enough to be considered under the ‘vulnerable’ category (>30% decline over ten years or three generations). [19]While IUCN Red List was created for the purpose of aiding policy and conservation planning, it is limited by the criteria that determines the vulnerability of a species. [20] This starts with the fact that IUCN rankings are only available for species, which highlights an inherent problem with conservation efforts being centred around a collective species without considering its phylogeny and their evolutionary history.[21] There must be conservation efforts that take into consideration the genetic diversity of a species to ensure that the population of the species around the world is a healthy one. Taking the Asian Fairy-bluebird as an example, the population has genetically diversified by reproductive isolation.[22] However, they are part of the same species Irena puella, and therefore the subspecies contribute to the gene pool. Therefore, conservation should be dealt with on a regional or global level, instead of focusing conservation efforts by countries. The section below on the population of the Asian Fairy-bluebird explains how the species may be extremely vulnerable in individual states, but not reflected in the IUCN criteria.

5.2 Singapore

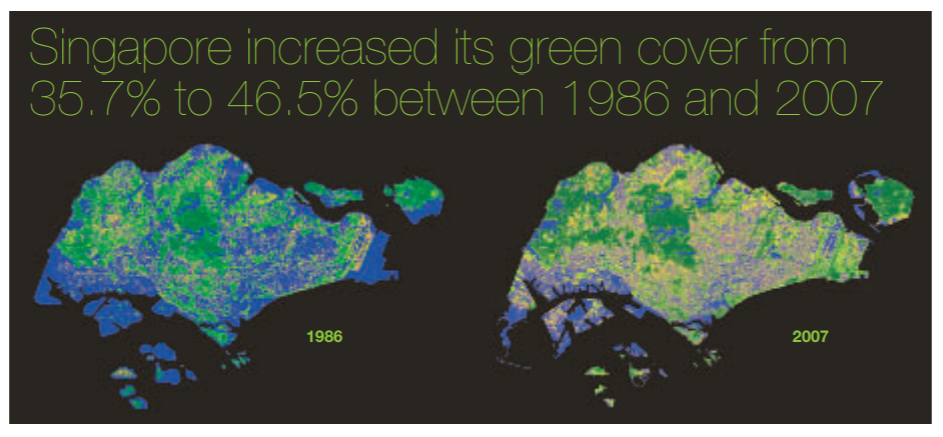

Extending this problem of conservation to Singapore in isolation, the population trend of this charismatic species is on a decline.[23] The total bird count from 1998 to 2005 is at mere 126 individuals, which is 0.14% of Singapore’s total bird count in this period, ranking 69 out of 100 in commonness. [24] This shows that while IUCN views this species as sufficiently abundant and widespread, in Singapore alone, it is not the case. Limitations to migration into other forest is difficult, as the CCNR is a relatively isolated forest in the middle of an urbanised nation [25] . It is a common misconception that the ability of flight grants them endless mobility, as birds require specific conditions to thrive, such as food, shelter and cover from predators. [26] For the Asian Fairy-bluebird, a high treetop and forest berries are the main determinants of their survival. [27] It is therefore possible that with increasing urbanisation of South East Asia and South Asia, their habitats will be rapidly destroyed. |

| Vegetation cover map of 1986 and 2007. Source: Nparks [free use] |

We run into another problem, which is the idea of sustainable, green development in Singapore. In our ‘garden city', urban greenery such as parks and roadside trees are in abundance. In a study of effects of rainforest fragmentation and commercial plantation in Western Ghats, India, it was shown that plantations drastically reduced species diversity of endemic birds, including the Asian Fairy-bluebird. [28] This shows that regardless of the percentage of tree covered areas in Singapore, species that are not generalists will not be able to survive in any green area, be it plantations or public parks. However, it must be noted that such artificial green areas provide important ecosystem services, such as carbon sequestration and reduction of urban heat. [29] These worrying trends may lead to the loss of our beautiful bluebird from our forests forever.

6. Taxonomy

6.1 Taxonavigation

Kingdom: AnimaliaPhylum: Chordata

Class: Aves

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Irenidae Jerdon, 1863

Genus: Irena Horsfield, 1821

Species: Irena puella (Latham, 1790)

6.2 Specimen Type

The type specimen of this species is preserved in the Museum of Zoology (University of Michigan). It was collected by Steere in 1877. |

| Specimen type of Irena tweeddalii Photo Credit: University of Michigan [CreativeCommons] |

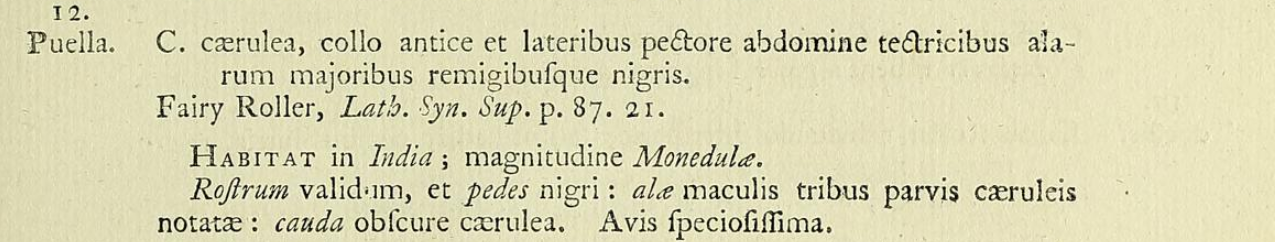

6.3 Initial description

Irena puella was originally classified under Coracias (Roller family) by an English naturalist named Latham in his book Index Ornithologicus (1790). Its common name was then the Fairy Roller. This might be due to the iridescent plumage on its crown that is similar to those on the Rollers. |

| Indian Roller (Coracias benghalensis)[CreativeCommons] |

A rough translation of Latin to English of Latham’s work on birds shows a brief description of the black and blue body parts of the male, as well as its medium body size.

|

| Original description by Latham in Index Ornithologicus (1790)Retrieved from Smithsonian Libraries (Fair use) |

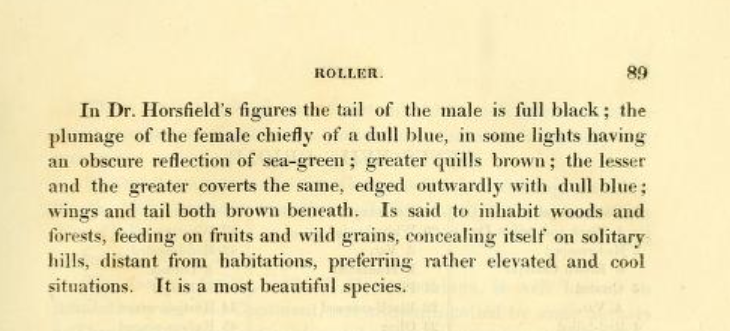

Thomas Horsfield, who visited the Java reclassified them under Irena. In Zoological Researches in Java and the Neighbouring Islands (1824), he includes sketches of both male and female. He drew closer links to the drongos and orioles than the Rollers by comparing the morphology of orioles and the Asian fairy bluebird and saw similarities in their beaks. Horsfield quotes Sir Stamford Raffles in this work: ‘adverting to the form of the bill, compressed, carinated and notched, it seems doubtful whether this bird be truly a species of Coracias’.

|

| Sketches of a male Asian fairy bluebirdPhoto credit: taken from Smithsonian Library [free use] |

|

| Sketches of female Asian fairy bluebirdPhoto credit: taken from Smithsonian Library [free use] |

6.4 Etymology

|

| Latham’s description of the Asian fairy bluebird in 1821Photo credit: taken from Smithsonian Library [free use] |

It is interesting to note that the species name puella is very often used in other species.

|

| Barred Hamlet (Hypoplectrus puella) [CreativeCommons] |

|

| Nigma puella [CreativeCommons] |

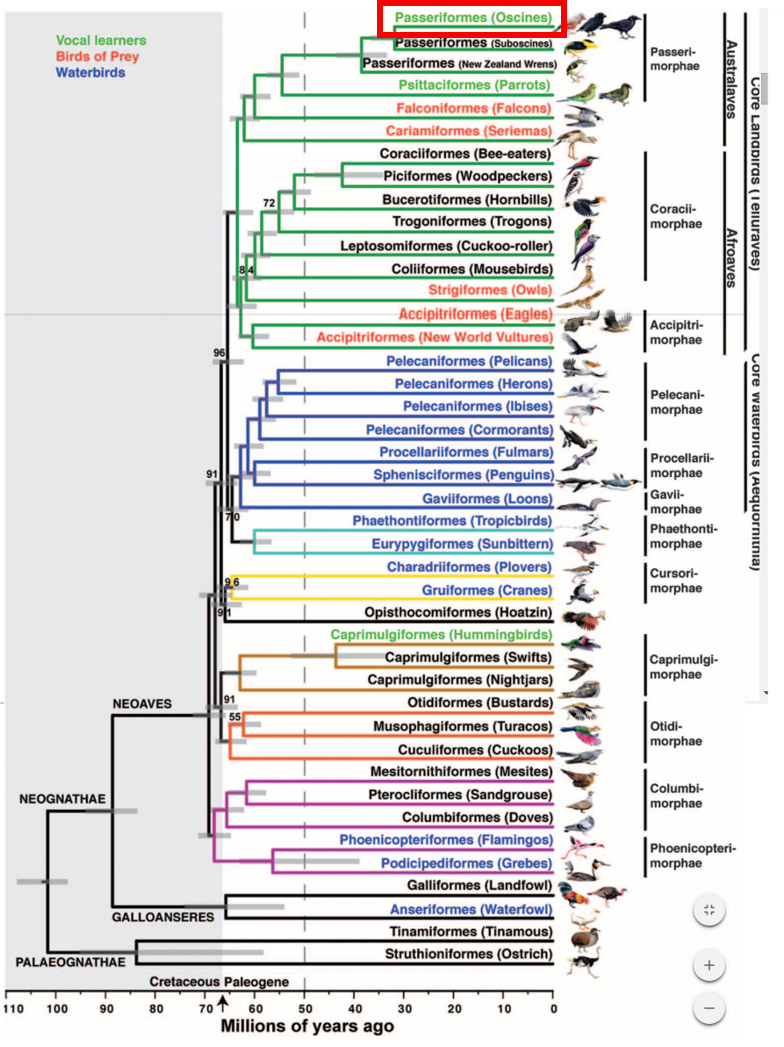

6.5 Phylogeny

In the Aves phylogenetic tree, the Asian Fairy-bluebird is placed under Passeriformes, under a suborder named Passeri (or simply oscines). Oscines differ from suboscines in their syrinx, which allows them to produce various vocalisation. [30] In Jarvis et al. ‘s work on phylogeny of birds, branch colour shows well-supported clades, and the colours of the words groups the species with broadly shared traits, whether by homology or convergence. [31] |

| Aves phylogeny tree by Jarvis et al. [free use] |

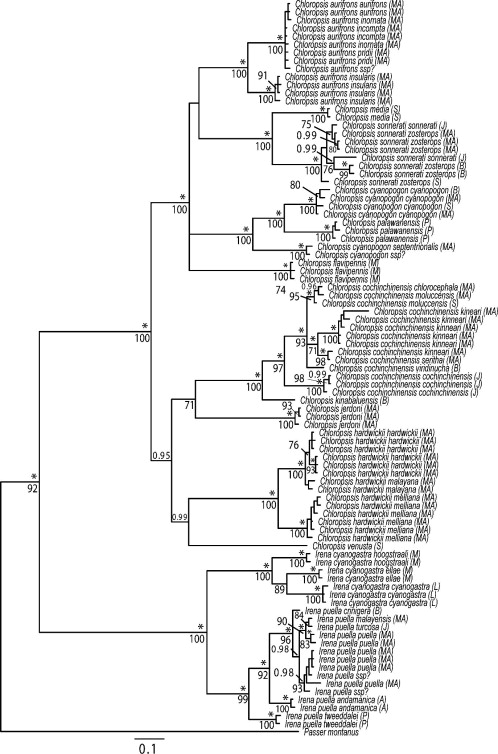

A study by Moltesen et al. (2012), who noticed that the oscines were ‘based on a practical subdivision of some major eco-morphological groups’, with no serious attempt at a phylogenetic analysis. The two related families Chloropseidae (leafbirds) and Irenidae were compared for two nuclear introns (GAPDH and ODC) and two mitochondrial genes (ND3 and cyt-b). It was likely that the two families descended from a common passerine ancestor in the Southeast Asia region, based on their similarities in body shape, colourful plumage, short legs and fruit-dependent diet. This ancestral population may have been reproductively isolated due to physical barriers caused by plate tectonics which split up islands.[32]

Using Bayesian inference and Maximum Likelihood of concatenated dataset gave a very well-supported tree which they obtained below (presented as a 50% majority rule consensus from Bayesian analysis):

|

| 50% majority rule consensus tree of Chloropseidae and Irenidae obtained from the Bayesian analysis by Moltesen et al. (2012)Photo credit: Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution [free use] |

The bootstrap values are clearly near 100, showing that the nodes are well-supported for the Irena species, and for the Irena puella and the subspecies as well. This showed that classification by morphology (mainly plumage) was in line with the molecular phylogeny data.[33]

|

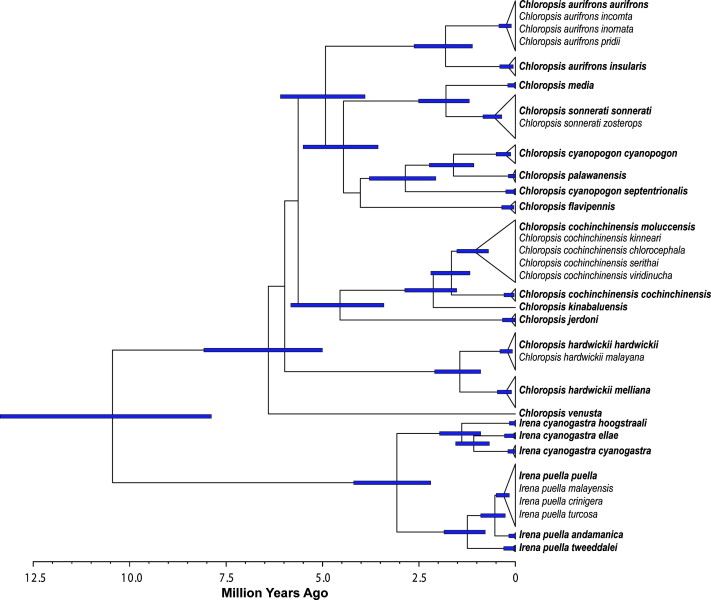

| Chronogram based on the BEAST analysis of Chloropseidae and IrenidaePhoto credit: Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution [free use] |

A chronogram was derived by applying the 2% rule on BEAST v. 1.5. The blue lines are the node bars that indicate 95% highest posterior density intervals. This can be interpreted as having a 95% credibility interval in Bayesian analysis. They concluded that Chloropseidae and Irenidae diverged from the ancestral species which existed in the Asian mainland in the Miocene (10-11 million years ago), which coincides with the tectonic movements that shifted plates and microplates. This resulted in colonisation of the separated islands by the population that led to genetic divergence.[34]

6.6 Subspecies

Irena puella andamanica Abdulali, 1964Irena puella crinigera Sharpe, 1877

Irena puella malayensis Moore, 1854

Irena puella puella (Latham, 1790)

Irena puella turcosa Walden, 1870

Irena puella tweeddalii Sharpe, 1877

The six subspecies can be divided into those with long or short tail coverts. Populations with long upper tail coverts are turcosa, crinigera and malayensis from the Southern area, while shorter tail coverts are observed in puella and adamanica and tweeddalii of the Northern and Western areas.[35] The only subspecies present in Singapore is the Irena puella malayensis.[36] Moltesen interprets this ‘leapfrog’ in morphology to indicate the genetic complexity in this species.[37]

Works Cited

13seaeagle. (2012). Asian Fairy-bluebird(M) n Greater Racket-tailed Drongo @ Bukit Timah Nature Reserve-Singapore. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JnNpaisHhV0&.Bellerby, D. (2015). Black-naped Oriole. Retrieved from https://www.flickr.com/photos/world-birds/22172783789/.

Dupont, B. (2015). Dictynid Spider (Nigma puella) catching a small fly (Muscidae). Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dictynid_Spider_(Nigma_puella)_catching_a_small_fly_(Muscidae)_(16615458783).jpg.

eBird. (n.d). eBird map. Retrieved from http://ebird.org/ebird/map/asfblu1?neg=true&env.minX=&env.minY=&env.maxX=&env.maxY=&zh=false&gp=false&ev=Z&mr=1-12&bmo=1&emo=12&yr=all&byr=1900&eyr=2017.

Horsfield, T. (1824). Zoological researches in Java, and the neighbouring islands. Retrieved from https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/44848#/summary.

Ilyes, L. (2002). Left profile of a Barred Hamlet (Hypoplectrus puella). Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hypoplectrus_puella.jpg.

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. (2017). Irena puella. Retrieved from http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/103775156/0.

Jarvis, E. D., Mirarab, S., Aberer, A. J., Li, B., Houde, P., Li, C., ... Zhang, G. (2014). Whole-genome analyses resolve early branches in the tree of life of modern birds. Science, 346(6215), 1320-1331. DOI: 10.1126/science.1253451. Retrieved from http://science.sciencemag.org.libproxy1.nus.edu.sg/content/346/6215/1320/tab-figures-data.

Kuveskar, S. (2016). Indian Roller Coracias benghalensis, in Mangaon, Maharashtra, India. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indian_roller#/media/File:Indian_roller_(Coracias_benghalensis)_Photograph_by_Shantanu_Kuveskar.jpg.

Latham, J. (1790). Index Ornithologicus. Retrieved from https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/131313#/summary.

Latham, J. (1821). A General History of Birds. Retrieved from https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/62572#/summary.

luminous birding. (2017). Asian Fairy-bluebird, Irena puella, Eating fruits from a tree. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xo7F0j0tZRI.

Moltesen, M., Irestedt, M., Fjeldså, J., Ericson, P. G., & Jønsson, K. A. (2012). Molecular phylogeny of Chloropseidae and Irenidae – Cryptic species and biogeography. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 65(3), 903-914. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com.libproxy1.nus.edu.sg/science/article/pii/S1055790312003211?via%3Dihub.

morano.vincent. (2008). Tigmamanukan. Retrieved from https://www.flickr.com/photos/30326710@N02/2852193269/.

NParks. (2009). Conserving our Biodiversity: Singapore's Nationanl Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan. Retrieved from https://www.nparks.gov.sg/biodiversity/our-national-plan-for-conservation/~/media/nparks-real-content/biodiversity/national-plan/nbsap_2009.ashx.

Owen, B. (2010). Male Asian Fairy-bluebird. Retrieved from https://www.flickr.com/photos/82432080@N00/4516970751.

Rosell, N. T. B. (2012). Philippine Fairy-bluebird (Irena cyanogastra) Endemic. Retrieved from https://www.flickr.com/photos/neon2rosell/8163440525/in/photostream/.

Spaan, V. (n.d.). Irena puella. Retrieved from http://www.buulbuul.nl/Irena%20puella.html.

University of Michigan. (n.d.) Irena Tweeddalii. Retrieved from https://lsa.umich.edu/ummz/birds/collections/orderResult.asp?cOrder=Passeriformes&offset=90.

Yap, F. (n.d.). Asian Fairy-bluebird at Jelutong Tower. Retrieved from https://singaporebirds.com/species/asian-fairy-bluebird/.

Yap, F. (n.d.). Female Asian Fairy-bluebird at Jelutong Tower. Retrieved from https://singaporebirds.com/species/asian-fairy-bluebird/.

Yap, F. (n.d.). Helping a dull bird shine - Greater Racket-tailed Drongo. Retrieved from https://fryap.wordpress.com/2014/07/26/helping-a-dull-bird-shine-greater-racket-tailed-drongo/.

Yee, A. T. K., Corlett, R. T., Liew, S. C. & Tan, H. T. W. (2011). The vegetation of Singapore - An updated map. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280601159_The_vegetation_of_Singapore_-_An_updated_map.

Scott, William Henry (1994). Barangay: Sixteenth Century Philippine Culture and Society. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press. ISBN 971-550-135-4.

Yong, D. L., Lim, K. C. and Lee, T. K. (2016) A Naturalist’s Guide to the Birds of Singapore 2nd ed., Singapore: John Beaufoy Publishing

Lim, K. S. (2009) The Avifauna of Singapore. Singapore: Nature Society (Singapore) Bird Group Records Committee, page 281.

Wong, T. S. (2017) A Naturalist’s Guide to the Birds of Borneo; Sabah, Sarawak, Brunei and Kalimantan. Singapore: John Beaufoy Publishing

Yong, D. L., Lim, K. C. and Lee, T. K. (2016) A Naturalist’s Guide to the Birds of Singapore 2nd ed., Singapore: John Beaufoy Publishing

Myers, S. and Allen. R. (2009) A Field Guide to the Birds of Borneo. New Holland.

Ng, P. K. L., Tan, H. T. W. & Corlett, R. T. (2011). Singapore Biodiversity. An Encyclopedia of the Narual Environment and Sustainable Development. Singapore: Editions Didier Millet. Page 552.

Briffett, C. and Bin Supari, S. (1993) The Birds of Singapore. Oxford University Press.

BirdLife International. (2016). Irena puella. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T103775156A93991401.Retrieved from http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/103775156/0. (accessed on 22 Nov 2017).

Schachat, S. R., Mulcahy, D. G. And Mendelson II, J. R. (2015). Conservation threats and the phylogenetic utility of IUCN Red List rankings in Incilius toads. Conservation Biology, 30(1), pp 72-81.

Lim, K. C. and Lim. K. S. (2009). State of Singapore’s Wild Birds and Bird Habitats: A Review of the Annual Bird Census 1996-2005. Singapore: Nature Society (Singapore) Bird Group, pp 237.

Shankar Raman, T. R. (2006). Effects of Habitat Structure and Adjacent Habitats on Birds in Tropical Rainforest Fragments and Shaded Plantations in the Western Ghats, India. Biodiversity & Conservation, 15(4), pp 1577-1607.

Moore, J. M., Székely, T., Büki, J. & DeVoogd, T. J. (2011). Motor pathway convergence predicts syllable repertoire size in oscine birds. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 108(39), pp 16440-16445.

Moltesen, M., Irestedt, M., Fjeldså, J., Ericson, P. G., & Jønsson, K. A. (2012). Molecular phylogeny of Chloropseidae and Irenidae – Cryptic species and biogeography. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 65(3), 903-914. DOI: 10.1016/j.ympev.2012.08.012.

Moltesen, M., Irestedt, M., Fjeldså, J., Ericson, P. G., & Jønsson, K. A. (2012). Molecular phylogeny of Chloropseidae and Irenidae – Cryptic species and biogeography. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 65(3), 903-914. DOI: 10.1016/j.ympev.2012.08.012.

Moltesen, M., Irestedt, M., Fjeldså, J., Ericson, P. G., & Jønsson, K. A. (2012). Molecular phylogeny of Chloropseidae and Irenidae – Cryptic species and biogeography. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 65(3), 903-914. DOI: 10.1016/j.ympev.2012.08.012.

Moltesen, M., Irestedt, M., Fjeldså, J., Ericson, P. G., & Jønsson, K. A. (2012). Molecular phylogeny of Chloropseidae and Irenidae – Cryptic species and biogeography. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 65(3), 903-914. DOI: 10.1016/j.ympev.2012.08.012.

Lim, K. S. (2009) The Avifauna of Singapore. Singapore: Nature Society (Singapore) Bird Group Records Committee, page 281.