|

| (Photo: Kenny Chua) |

Introduction

Table of Contents

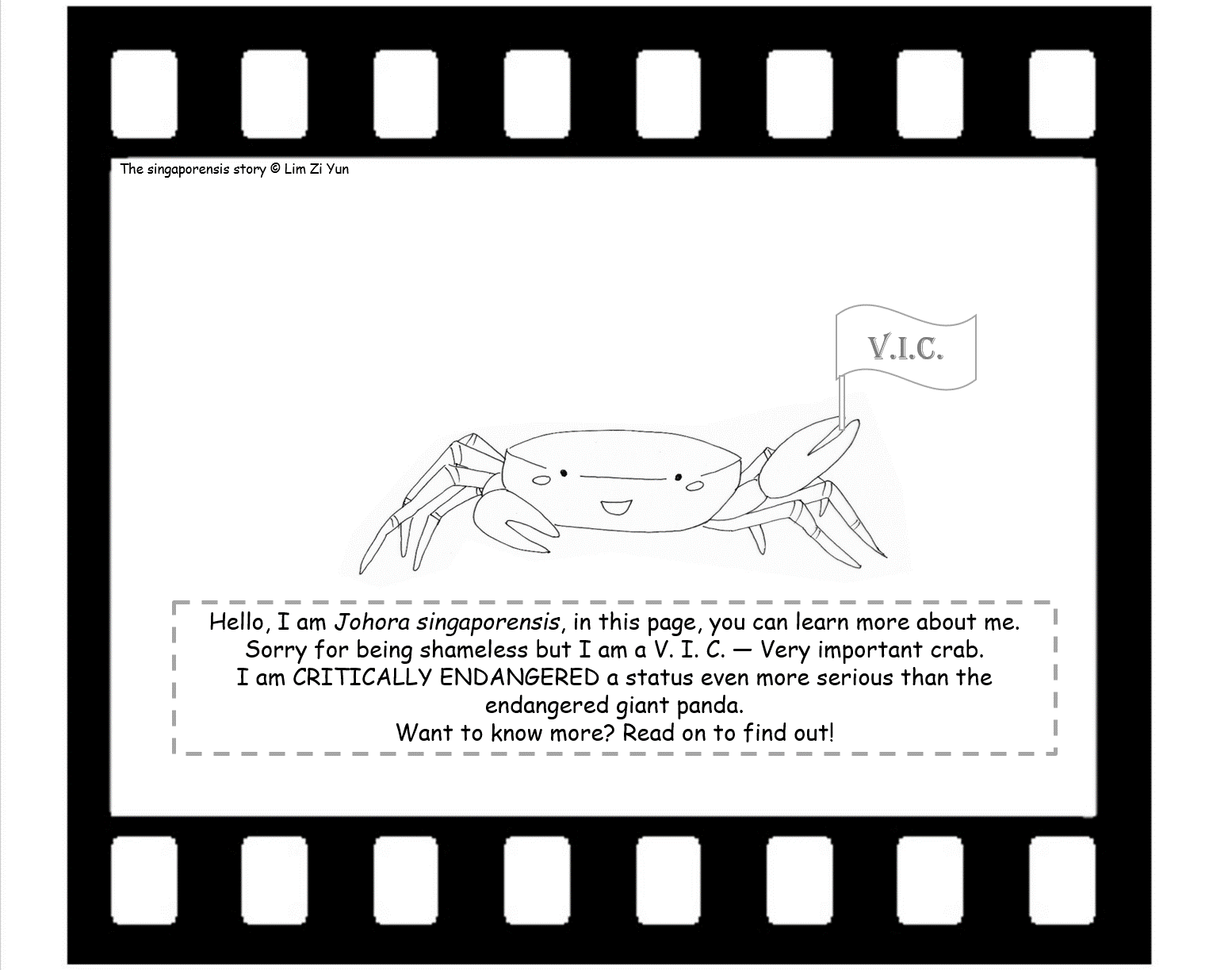

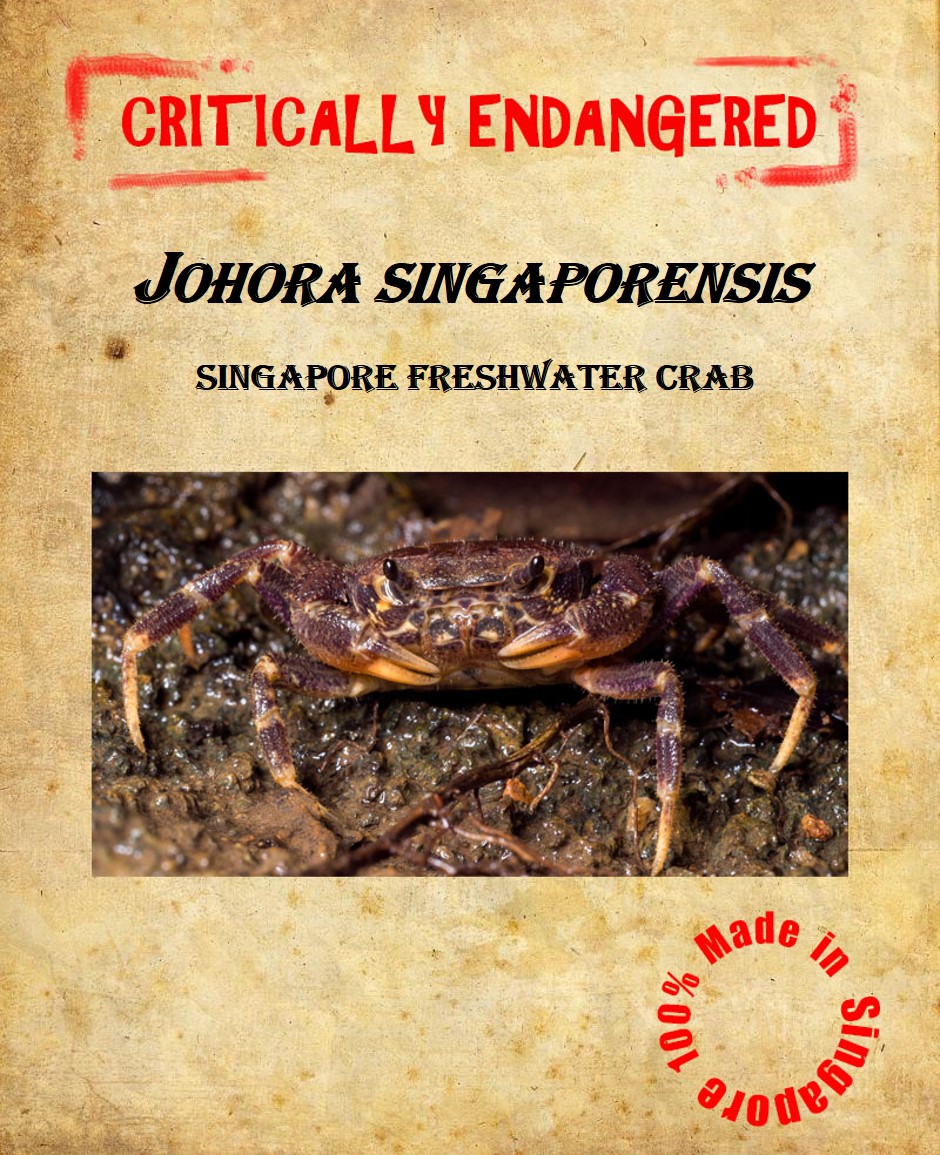

Johora singaporensis is endemic to Singapore (i.e. can only be found in Singapore) and its distribution on the island is highly restricted (refer to Distribution). In fact, it was regarded as critically endangered by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) (3). During the IUCN’s world Conservation Congress, it was included in the list of the top 100 most threatened species in the world (4). Like other freshwater decapods, they are scavengers and detritivores which play an important role in the recycling of nutrients in the freshwater ecosystem (5).

Name

Etymology (how it got its name): The species is named after its locality, Singapore, where it is endemic to.Binomial name (scientific name): Johora singaporensis Ng, 1986

Vernacular name (common name): Singapore freshwater crab or Singapore stream crab

Synonyms (scientific names that were previously used):

Potamon (Potamon) johorense Roux 1936

Potamon johorense Ong 1965

Potamiscus (Johora) johorensis johorensis Bott 1966

Stoliczia (Johora) johorensis johorensis Bott 1970

Distribution

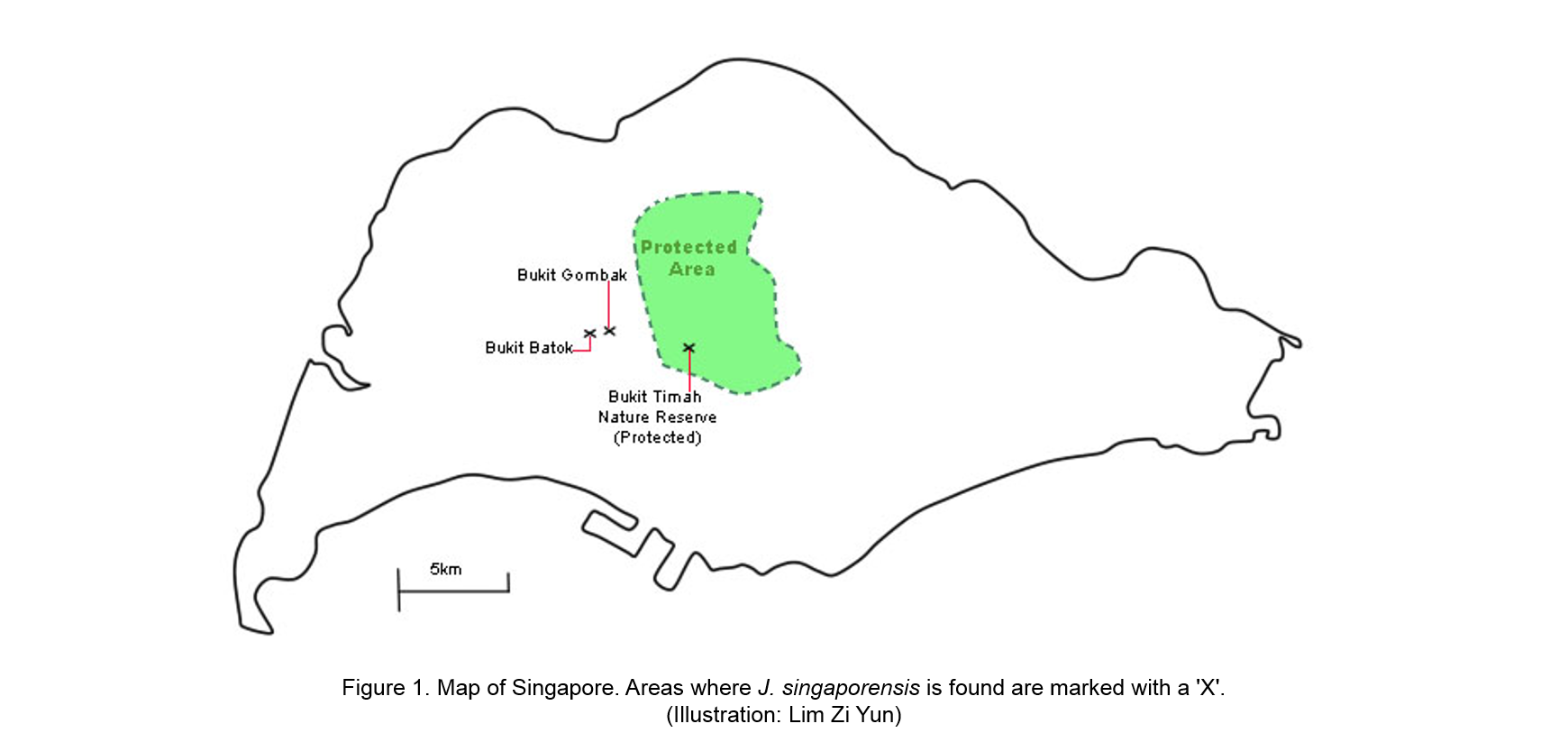

Johora singaporensis can only be found in Singapore. It only inhabits certain streams near Bukit Timah, Bukit Batok and Bukit Gombak (Figure 1)

Biology

Diet

In general, freshwater decapods are nocturnal and regarded as scavengers and omnivores (6, 7, 8

|

| Figure 2. Feeding on a dead mole cricket. (Photo: Daniel Ng) |

Johora singaporensis has been recorded to predate on oligochaetes found in soft mud to supplement its diet of mainly detritus (9, 10). Recently, J. singaporensis was observed to scavenge on a dead mole cricket out of water (Figure 2). This behaviour was reported to be unusual as the behaviour of feeding on terrestrial insects out of water have never been recorded (11). As compared to sympatric species like Irmengardia johnsoni and Parathelphusa maculata, J. singaporensis is observed to prefer animal matter (12).

The video below shows close up of how a freshwater crab eats. The crab featured is Geosesarma peraccae, a freshwater crab that can be found in Singapore too. Unlike J. singaporensis, it is not endemic to Singapore and is semi-terrestrial.

Lifecycle

|

| Figure 3. A female carrying her little crablets in her abdomen. (Photo: Kenny Chua) |

The eggs of J. singaporensis, like all primary freshwater crabs, are large and yolky. Female crabs carry and brood the eggs in her abdomen where will hatch into tiny fully-formed crabs (Figure 3). The direct development of eggs is an important adaptation to life in freshwater streams. This avoids the free swimming larvae stage that is usually present for marine crabs.Free swimming larvae would most likely be washed downstream to the sea where they will most likely not survive. For the first couple of weeks, the mother will carry the newly hatched young in her abdomen until they are able to lead independent lives (12).

Osmoregulation and respiration

Living in freshwater conditions will result in the loss of body salts. Hence, Johora singaporensis is capable of reabsorbing salt from their urine for osmoregulation (5).

| Figure 4. Short periods without water can be tolerated. (Photo: Daniel Ng) |

Similar to all freshwater crabs, J. singaporensis spends quite some time in the terrestrial environment too (Figure 4). Hence, they possess “pseudo-lungs” in their gill chambers to allow them to breathe in atmospheric oxygen (5).

These adaptations allow J. singaporensis to survive in the short term without water. However, water is still essential for their survival due to the need to excrete ammonia (5).

Moulting

|

| Figure 5. Feeding on old exoskeleton (Photo: Daniel Ng) |

Crabs need to moult in order to grow. The crab will pump in water to swell its body resulting in the old exoskeleton to split at specific lines. During moulting, the crab is most vulnerable as any stress or disturbance may result in its death. The moulted crab is very soft and the hardening of the new exoskeleton via the incorporation of calcium salts from its reserves or the water will take a few days.

After the moult, the crab will eat more to grow into its larger exoskeleton (14). As forested freshwater streams has very little calcium salts, the old shell can be eaten by the crab after its mouthparts harden to conserve valuable calcium salts (Ng, 1988, 1990) (Figure 5).

Ecology

Habitat

Johora singaporensis is mainly an aquatic crab, but it can also survive out of water if the surroundings are humid and cool (13). They prefer streams in hilly areas, where| Figure 6. Habitat preference: clear, clean waters in forested streams. (Photo: Kenny Chua) |

Ecological services

Freshwater decapods play an important role in the nutrient cycling of the freshwater stream ecosystem (10, 15). Being equipped with pincer-like appendages for efficient shredding, Johora singaporensis and other freshwater decapods speeds up the decomposition process by tearing plant matter and rotting animal carcasses into smaller pieces.Conservation

|

| Photo: Kenny Chua; Artwork: Lim Zi Yun |

Why conserve?

Johora singaporensis is “uniquely Singaporean” as crab expert Professor Peter Ng mentioned in an article in The Straits Times (12 June 2013). 99% of the crabs in Singapore can be found in other parts of the world. Johora singaporensis evolved on the island in isolation and can only be found here.

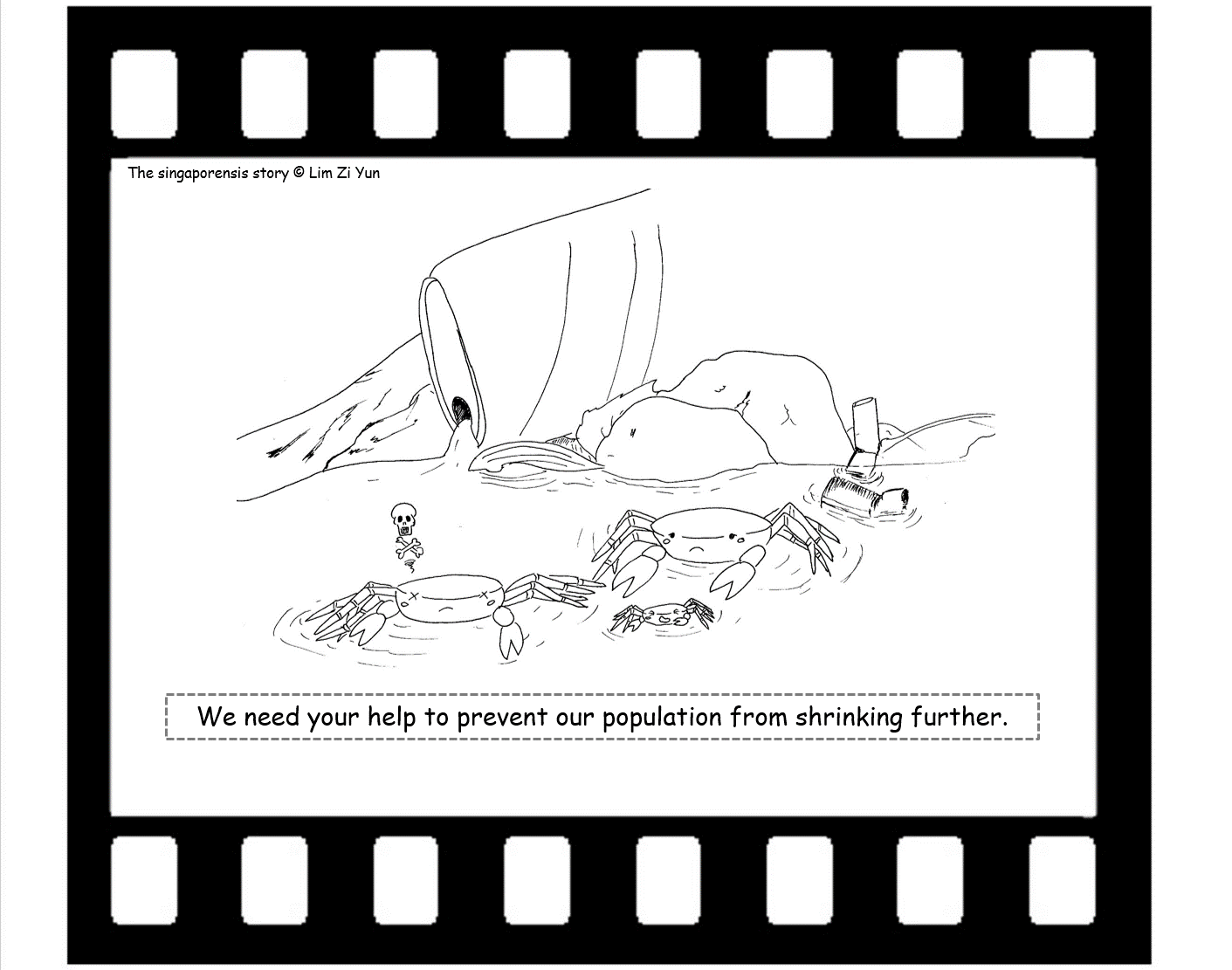

Singapore, being a small island, severely lacks areas with hilly streams. The distribution of Johora singaporensis is has been restricted to a few forest streams in Bukit Batok, Bukit Gombak and Bukit Timah. Only Bukit Timah has a designated protected reserve. In the past, the small 39 ha primary forest area was able to sustain a thriving population despite the deterioration of the rest of Bukit Timah Nature Reserve into a secondary forest and an abandoned farmland. Recently, it was found that the population in Bukit Timah has been drastically reduced and close to local extinction (2, 17It was postulated to be caused by the acidification of stream waters due to acid rain (2). Urban pollution resulting in the silting of waters may also degrade the pristine waters that J. singaporensis inhabits (16). Now, the crabs inhabit a 10 ha area that that is subjected to development (17). Populations that are remaining lie within unprotected areas, and hence may face habitat degradation.

No laughing matter

In the book “Priceless or Worthless”, where the top 100 most threatened species of the world was nominated by members of the IUCN Species Survival Commission Specialist Groups and Red List Authorities, Johora singaporensis was unfortunately one of the candidates (4).

In Singapore, newspaper articles on the plight of Johora singaporensis have been published to create public awareness.

|

| The Straits Times, June 12 2012 |

|

| The Straits Times, 8th August 2013 |

Is it possible to prevent the extinction of our unique crab?

More research can be done to understand more about Johora singaporensis – its breeding habits and the level of tolerance of its habitat parameters. A two-year project by Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research (RMBR) and National Parks Board (NParks) was initiated to study the status of Johora singaporensis, in attempt to strike its name off the 100 most threatened species list of the IUCN.

Preservation of its natural habitats is also crucial. Conservation of large patches of forest is needed to maintain the pristine water quality to allow J. singaporensis to thrive (17). When exploring nature reserves and other natural areas, we can also do our part by not littering or damaging vegetation. Take nothing but photographs and leave nothing but footprints behind.

Morphology

General body parts of a freshwater crab

Only the body parts used in the description will be labelled for reference.1. Dorsal View (Figure 7)

|

| Figure 7. Dorsal view of a freshwater crab. (Photo: Peter Ng; Labels: Lim Zi Yun) |

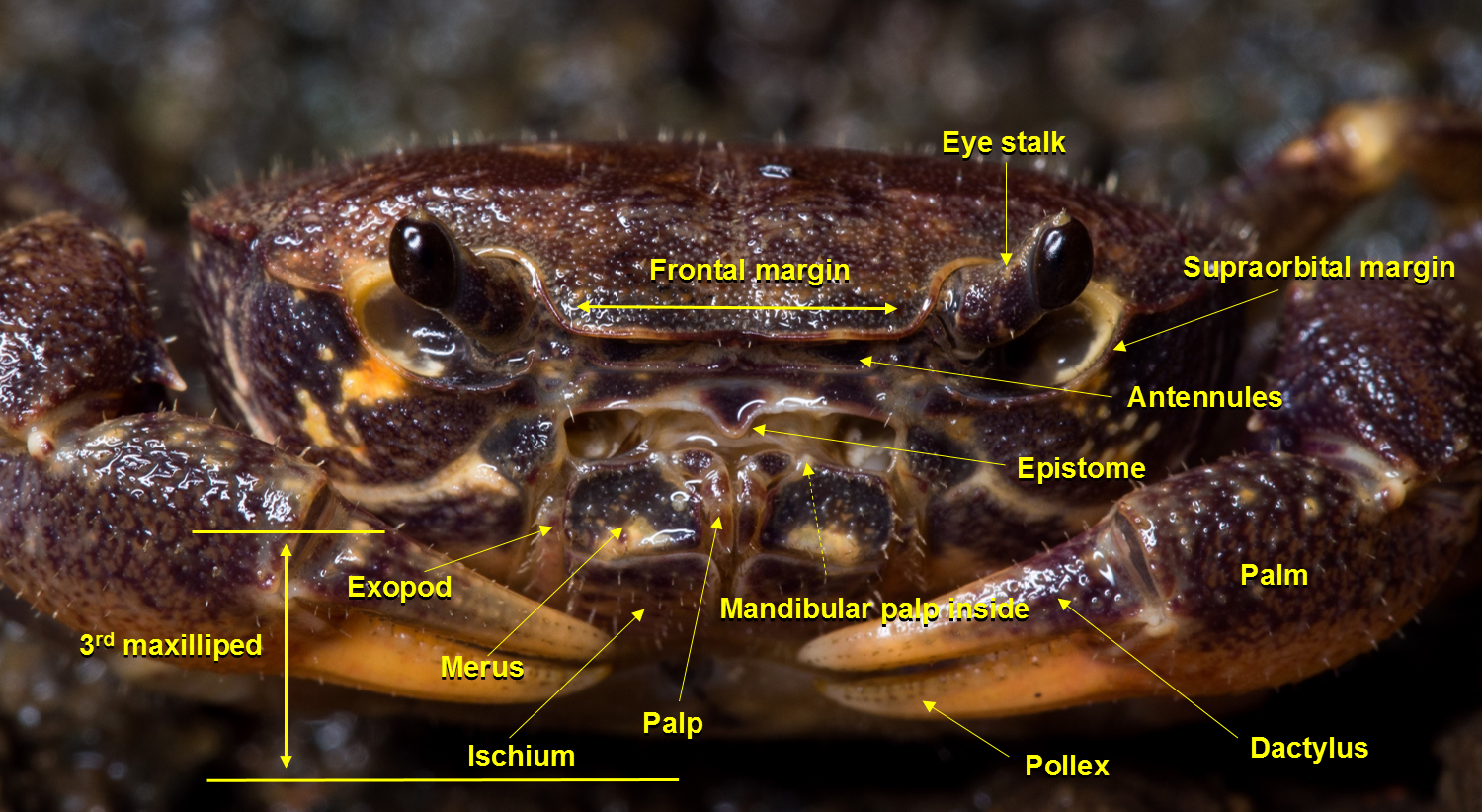

2. Frontal view (Figure 8)

|

| Figure 8. Frontal view of a freshwater crab. (Photo: Kenny Chua; Labels: Lim Zi Yun) |

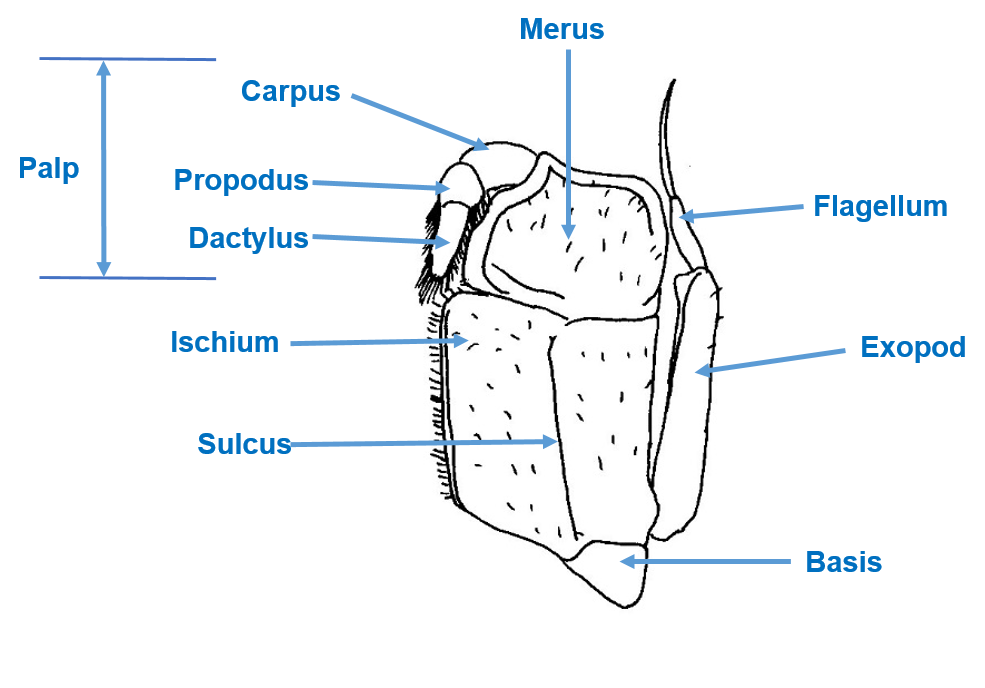

3. Third maxiliped (Figure 9)Crabs have a pair of third maxilipeds that cover their mouth.

|

| Figure 9. Parts of the right third maxiliped (re-illustrated from Ng, 1987) |

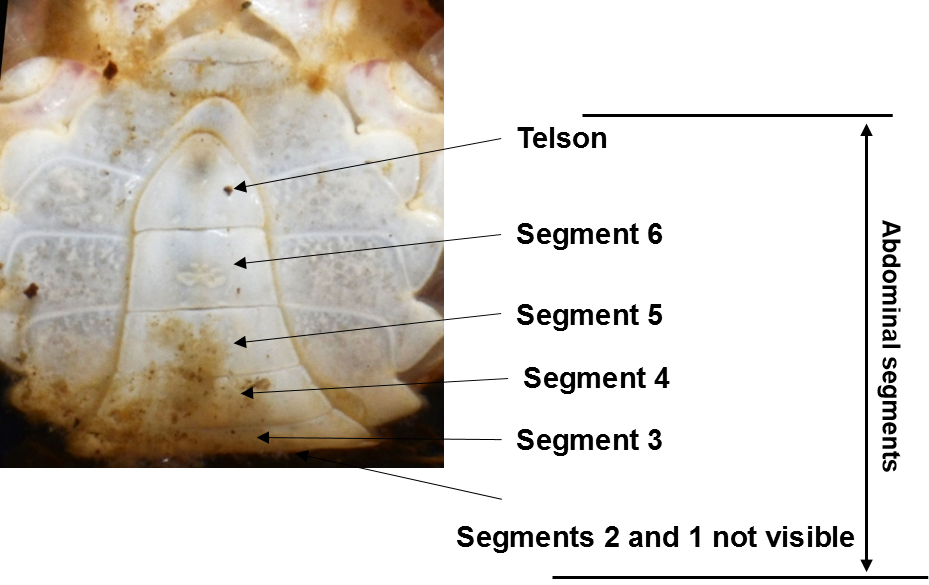

4. Ventral View (Figure 10)

|

| Figure 10. Ventral view of a freshwater crab. (Photo: Daniel Ng; Labels: Lim Zi Yun) |

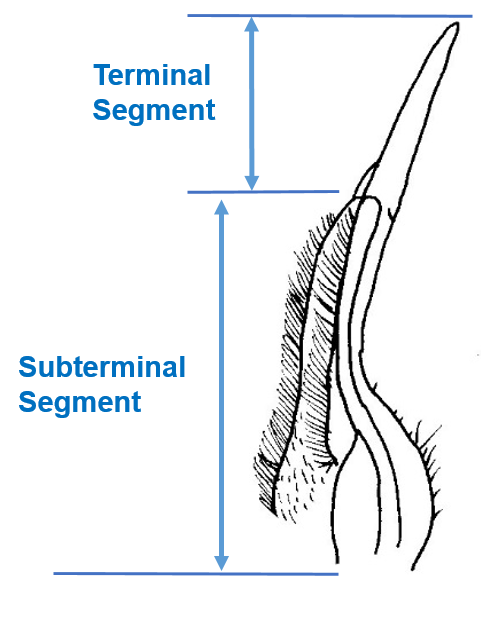

5. Gonopod 1 (G1) (Figure 11)

A pair of gonopods is found in the abdominal cavity (under the abdominal flap) of male crabs. They serve a copulatory function. Being tubular, they assist the transfer of spermatophores to the females. In freshwater crab taxonomy, these structures are extremely important as they are usually used for species identification.

|

| Figure 11. Parts of Left G1, ventral view (re-illustrated from Ng, 1987) |

Description of Johora singaporensis

Do note that colour is generally not used for species identification in freshwater crabs. Firstly, colour is perceived differently for different people. Secondly, in preserved specimens, the colours are usually faded.However, in the field, preliminary species identification can be done using colour before more detailed studies. Hence, colour is included in the description below (9,14,18).

| View |

Part |

Characteristic |

|||

| Carapace |

|

|

|||

| Dorsal |

Cheliped |

|

|

||

| Ambulatory Legs |

|

|

|||

| Frontal |

Third Maxiliped |

|

|

||

| Ventral |

Abdomen |

|

|

||

| Internal |

G1 |

|

|

Diagnosis

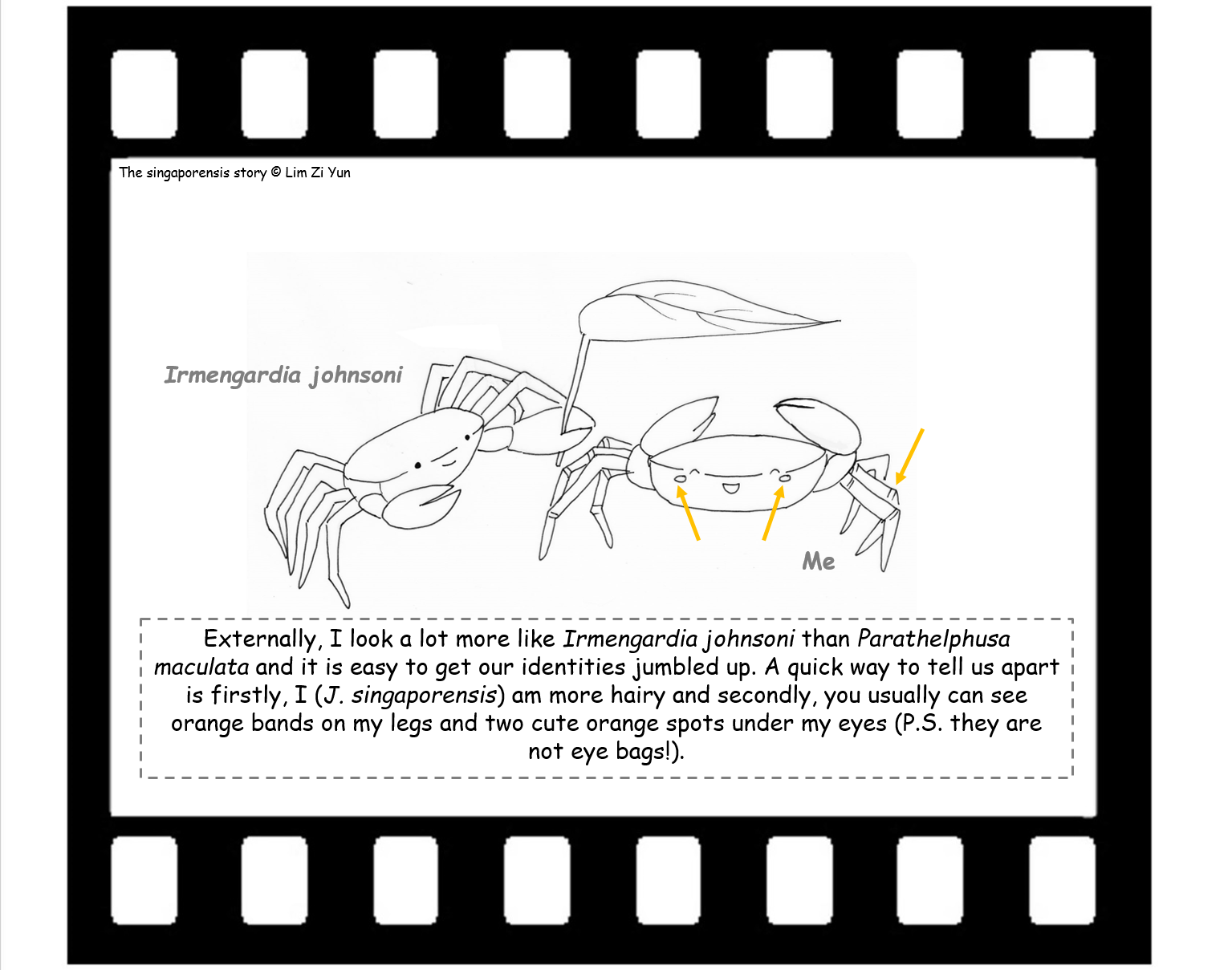

In Singapore, there are two other species of freshwater crabs that are mainly aquatic, Parathelphusa maculata and Irmengardia johnsoni.

Parathelphusa maculata also known as the lowland freshwater crab, is one of the most common crabs not only in Singapore, but also Malaysia (13). As it can be seen from their vernacular name, they prefer lowland streams. These hardy crabs have a high tolerance for low oxygen conditions and can be found in muddy waters and stagnant pools.

Irmengardia johnsoni or Johnson’s freshwater crab like Johora singaporensis, is endemic to Singapore. Although it is recorded to have a less restricted distribution than J. singaporensis, it is still considered vunerable by the IUCN. Unlike J. singaporensis which are found in highland streams, I. johnsoni can be found in secondary lowland streams too, where they inhabit leaf litter of muddy areas (14).

How can Johora singaporensis be differentiated from other mainly aquatic freshwater crabs of Singapore?

In the field:

In the field, it is often not possible to differentiate the crabs based on internal structures. Hence, the table below shows other characters that can help the identification of Johora singaporensis.| Johora singaporensis |

Parathelphusa maculata |

Irmengardia johnsoni |

|||||||

| Carapace |

•Covered with short stiff hairs •Low and indistinct epibranchial tooth on anterolateral margin •Colouration: Dirty brown with purplish tinge |

•No hairs •Two epibranchial teeth on anterolateral margin •Colouration: Olive to dark brown, younger specimens have a light olive brown carapace with spots which gradually fade off as they grow |

•No hairs •Low and indistinct epibranchial tooth on anterolateral margin •Colouration: Dirty dark grey or brown |

||||||

| Chelipeds |

•Colouration: Brown, with lower parts orange and inner surface of the chelipedmerus purplish red |

•Colouration: Brown, covered with darker brown spots |

•Colouration: Bright orange in larger specimens, brown in smaller specimens |

||||||

| Ambulatory legs |

•Colouration: Brown with narrow proximal lateral light orange strip giving it a banded appearance,dactyli more orange |

•Colouration: Brown |

•Colouration: Dirty dark grey or brown |

||||||

| Habitat preference |

|

|

|

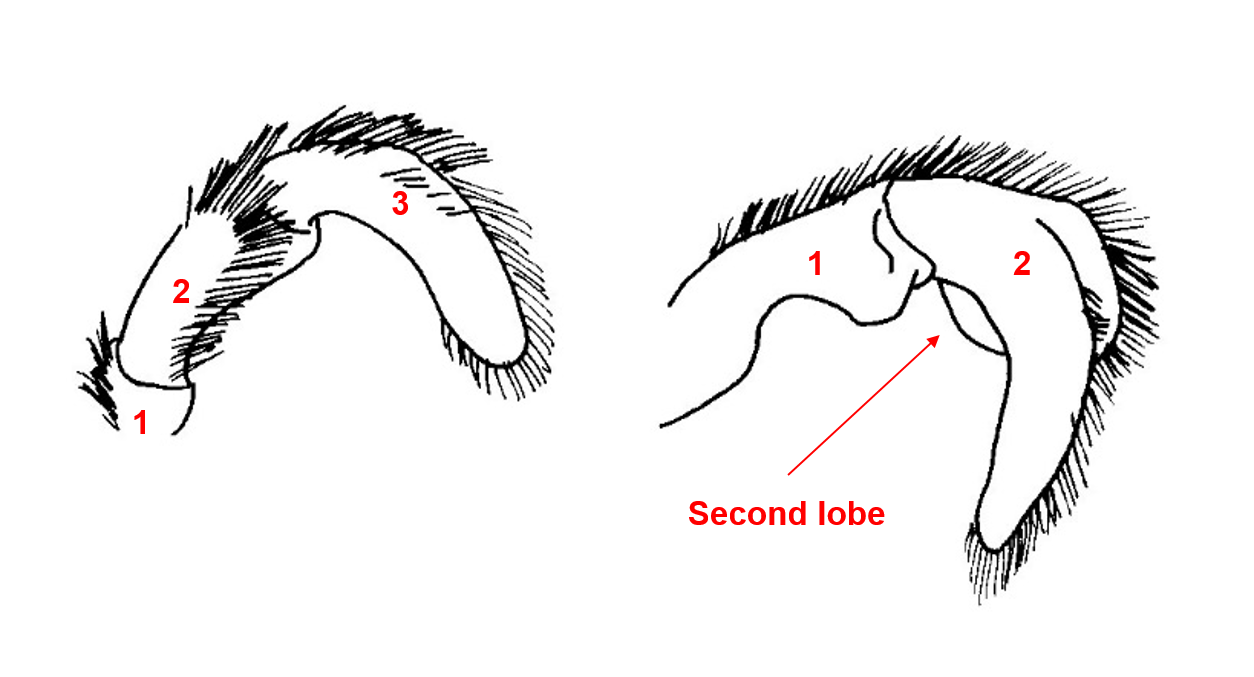

In the laboratory:

In laboratory conditions, it is easy to distinguish Johora singaporensis from Irmengardia johnsoni and Parathelphusa maculata. J. singaporensis belongs belongs to the family Potamidae while I. johnsoni and P. maculata belongs to Gecarcinucidae. Using a higher magnification, we can use these two features below to accurately identify J. singaporensis.- Potamids (where J.singaporensis belongs) have a 3-segmented mandibular palp with a simple terminal segment whereas gecarcinucids (I. johnsoni and P. maculata) have a 2-segmented bilobed mandibular palp (19) (Figure 12).

|

| Figure 12. Mandibular palps. Left: Potamid. Right: Gecarcinucid (re-illustrated from Ng, 1988) |

2. The G1s of the three species are very different (Figure 13).

|

| Figure 13. G1s |

Type information

The original description by Ng (1986) was based on the holotype.

Holotype: Male (17.3 by 14.0 mm) collected from Bukit Timah by P. K. L. Ng in 1984 (18). Currently stored in the Zoological Reference Collection (ZRC) of the Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research, National University of Singapore.

Paratypes:

| Year |

Number/ Sex |

Deposited in |

Collector |

Location |

| 1984 |

|

|

|

|

| 1984 |

|

|

|

|

| 1984 |

|

|

|

|

| 1985 |

|

|

|

|

| 1985 |

|

|

|

|

- Reference Collection of the Chulalongkorn University

- Rijksmuseum van Natuurlijke Historie, Leiden, Netherlands

- Museum Zoologicum Bogoriense, Bogor, Indonesia

Phylogeny

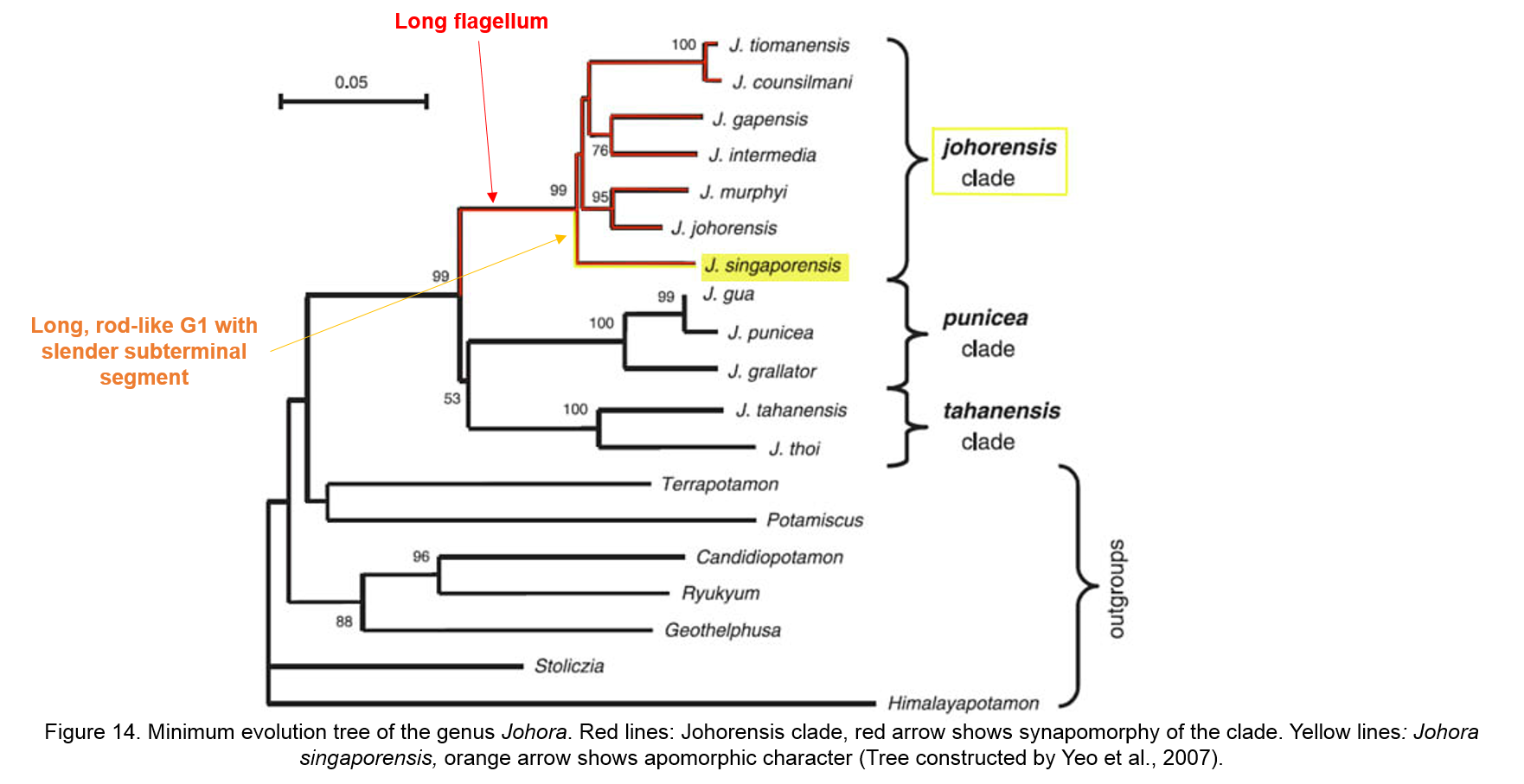

A minimum evolution tree based on the combined 16S rRNA, COI and H3 genes for the genus Johora was constructed by Yeo et al. (2007) (Figure 14) . Results show that Johora is a monophyletic clade, with three well developed clades within it. Johora used to be a subgenus of Stoliczia, however, in 1987, Ng elevated the group to a full genus and this is supported by the phylogenetic study.

Crabs of the genus Johora share a long flagellum on the exopod of the third maxilliped (i.e. main synapomorphy of Johora). Johora singaporensis belongs to the johorensis clade. Crabs of this clade are generally small- to medium-sized species, possess low epigastric and postorbital carapace cristae with a tapered and curved or hooked G1 terminal segment (20).

Johora singaporensis forms a monophyletic group that is sister taxa to the rest of the johorensis clade. The main apomorphic character of J. singaporensis is the long, rod-like terminal segment and very slender subterminal segment (9,14,18).

More information on freshwater crabs

A short introduction on Singapore's freshwater crabs

Singapore's freshwater crabs and shrimps

Freshwater crabs at risk of extinction

Literature cited

1) Ng, P. K. L., 1988. The Freshwater Crabs of Peninsular Malaysia and Singapore. Department of Zoology, University of Singapore, Shinglee Press, Singapore. 156 pp.

2) Tan, H. T. W., L. M. Chou, D. C. J. Yeo & P. K. L. Ng, 2010. The Natural Heritage of Singapore. 3rd Edition. Pearson Prentice Hall, Singapore. 323 pp.

3) Esser, L., N. Cumberlidge & D. C. J. Yeo, 2008. Johora singaporensis. In: IUCN 2012. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.1.http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/134219/0. (Accessed 10 Nov.2013).

4) Baillie, J. E. M. & E. R. Butcher, 2012. Priceless or worthless? The world’s most threatened species. Zoological Society of London, UK. 63 pp.

5) Dobson, M., 2004. Freshwater crabs in Africa. Freshwater Forum, 21: 3–26.

6) Dominey, W. J. & A. M. Snyder, 1988. Kleptoparasitism of freshwater crabs by cichlid fishes endemic to Lake Barombi Mbo, Cameroon, West Africa. Environmental Biology of Fishes, 22: 155–160.

7) Hill, M. P. & J. H. O’Keeffe, 1992. Some aspects of the ecology of the freshwater crab (Potamonautes perlatus Milne Edwards) in the upper reaches of the Buffalo River, Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. South African Journal of Aquatic Sciences, 18: 42–50.

8) Harrison, E. M., 1995. The zonation of freshwater crabs with altitude in a mountain stream in the East Usambara Mountains, Tanzania. Frontier Tanzania Expedition Report TZ943. Pp. 1–56.

9) Ng, P. K. L., 1987. A revision of the Malayan freshwater crabs of the genus Johora Bott, 1966 (Decapoda: Brachyura: Potamidae). Malayan Nature Journal, 41: 13–44.

10) Ng, P. K. L., 1988. The Freshwater Crabs of Peninsular Malaysia and Singapore. Department of Zoology, University of Singapore, Shinglee Press, Singapore. 156 pp.

11) Ng, D. J. J. & D. C. J., Yeo, 2013. Terrestrial scavenging behaviour of the Singapore freshwater crab, Johora singaporensis (Crustacea: Brachyura: Potamidae). Nature in Singapore, 6: 207–210.

12) Ng, P. K. L. & D. P., Maitland, 1986. The freshwater crabs of Singapore. Nature Malaysiana (Malaysia).11(2): 16–21

13) Ng, P. K. L., 1990. The freshwater crabs and prawns of Singapore. In: Chou, L. M. & P. K. L. Ng (eds.), Essays in Zoology. Department of Zoology, National University of Singapore, Singapore. Pp. 189–204.

14) Ng, P. K. L., 1988. The Freshwater Crabs of Peninsular Malaysia and Singapore. Department of Zoology, University of Singapore, Shinglee Press, Singapore. 156 pp.

15) Crowl, T. A., W. H., McDowell, A. P. Covich & S. L. Johnson, 2001. Freshwater shrimp effects on detrital processing and nutrients in a tropical headwater stream. Ecology,82:775–783.

16) Bahir, M. M. & D. E. Gabadage, 2012. Taxonomy and Conservation Status of the Freshwater Crabs (Crustacea: Decapoda) in Sri Lanka. In: Weerakoon, D. K. & S. Wijesundara (eds.) The National Red List 2012 of Sri Lanka: Conservation Status of the Fauna and Flora, Ministry of Environment, Colombo, Sri Lanka. Pp. 58–60.

17) Yeo, D. C. J., P. K. L. Ng, N. Cumberlidge, C. Magalhaes, S. R. Daniels & M. Campos, 2008. A global assessment of freshwater crab diversity (Crustacea: Decapoda: Brachyura). In: Balian, E. V., C. Leveque, H. Segers & M, Martens (eds.), Freshwater Animal Diversity Assessment. Hydrobiologia, 595: 275–286.

18) Ng, P. K. L., 1986. Preliminary descriptions of 17 new freshwater crabs of the genera Geosesarma, Parathelphusa, Johora and Stoliczia (Crustacea: Decapoda: Brachyura) from South East Asia. Journal of the Singapore National Academy of Science, 15: 36–44.

19) Cumberlidge, N. & P. K. L. Ng, 2009. Systematics, evolution, and biogeography of freshwater crabs. In: Martin, J. W., K. A. Crandall, & D.L. Felder (eds.), Crustacean Issues 18: Decapod Crustacean Phylogenetics. CRC Press, Boca Raton, pp. 491–508.

20) Yeo, D. C. J., H.-T. Shih, R. Meier & P. K. L. Ng, 2007. Phylogeography of the freshwater crab genus Johora (Crustacea: Brachyura: Potamidae) from the Malay Peninsula, and the origins of its insular fauna. Zoologica Scripta, 36: 255–269.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank:

Dr Darren Yeo and Daniel Ng for providing some papers for reference.

Kenny Chua and Lam Kar Mun for the photographs.

Lim Zi Min for cartoon inspirations.

Lam Kar Mun for her kind feedback.

Eunice Soh and Ong Xin Rui for website formatting help.