Table of Contents

uh-NEM-uh-nee? nem-MOH-nee?Sea anemones have gained popularity after the release of “Finding Nemo", where audiences learned of Marlin's harrowing journey to find Nemo after he was snatched away from their reef home. The clownfish and the sea anemones have a symbiotic relationship. Symbiotic relationship or symbiosis refers to close, long-term relationship between two different organisms; in this case the clownfish and the sea anemone. This relationship is found to be mutualistic with both parties benefiting: the clownfish that live within the anemone's tentacles recieve protection from their predators while the anemone feeds on scraps from the clownfishs' meal. Despite being one of the oldest living animal species on Earth, it is surprising to note that research on sea anemones is not as extensive compared to other animal studies.

Finding Nemo, Nemo saying sea anemone. Video taken by GeninSider[2]

Sea anemones are a group of marine predatory animals. They are named after the terrestrial flowering plant, the anemone due to the bright coloration of many sea anemone species. Often mistaken for corals, sea anemones are able to change their shape dramatically, lengthening and contracting column and tentacles at will, even bending and twisting.

Sea anemones may come in different colour, shapes and size. They have also been found to differ in their behaviour! While most sea anemones are sessile or immobile, some sea anemones species such as the swimming anemone or Boloceroides mcmurrichi are able to swim. [3] The swimming anemone swims slowly by undulating its tentacles in a coordinated manner as shown in the video below. When the swimming anemone senses a predator, it is able to shed its tentacles much like a gecko losing its tail, in an attempt to distract the predator while it swims away.

Swimming sea anemone. Video taken by waymire5[4]

Compared to its colourful marine counterparts, Metapeachia tropica has a plain appearance, with an elongated body and a round aboral end. M.tropica is a burrowing sea anemone as shown in the video below, meaning they live in soft sediments with only the tentacles exposed. Burrowing sea anemones can be found at all latitudes of the world from the intertidal zones to the deep-water trenches; one notable example is the Edwardsiella andrillae which burrows in the ice shelves of Antarctica! [5]

Burrowing sea anemone. Video taken by Ian Stevenson[6]

Distribution

While originally recorded in the Madras Coast in India by Panikkar, the distribution of M.tropica is also found in both the east and west coasts of the Indian subcontinent. [7] They are also found in Singapore as mentioned in one recent study.[8] The distribution of M.tropica in Singapore is shown in the figure below.

Synpeachia tropica, a close relative of Metapeachia tropica, are usually found together with M.tropica. Both species belong to the family of Haloclavidae, a family of burrowing anemones, as they both burrow into soft sediment and have one siphonoglyph (a ciliated groove at one or both ends of the mouth of sea anemones and some corals) terminating at the mouth. S.temasek differs from M. tropica due to its reddish-brown column, as well as having 20 tentacles instead of 16 like Metapeachia.

Morphology

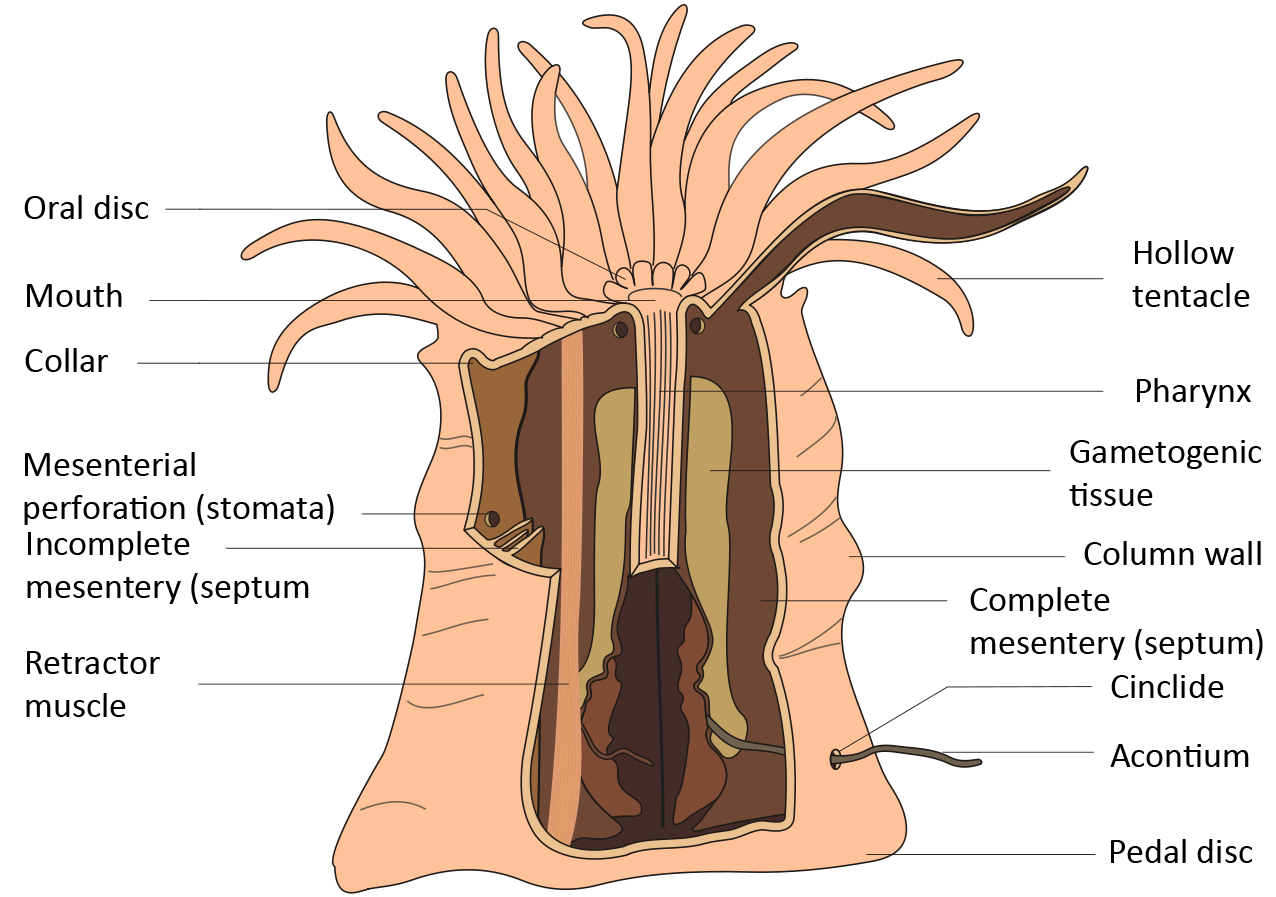

Metapeachia tropica shares similar morphological structures with other sea anemones. They attach themselves to substrates or rocks with an adhesive foot known as pedal disc to anchor themselves. They have a column-shaped body with an array of tentacles surrounding a central mouth. (Fig 4)

The cream-coloured column of M.tropica is long and has a worm-like structure with 16 tentacles. M. tropica also has a whitish-yellow column with reddish-brown markings at the base of the tentacles as can be seen in Fig 5. It has a patterned oral disc. During low tide, the tentacles are tucked into the body column, making this inconspicuous animal look like a white striped blob.

Figure 5: Left: specimen freshly removed from sediment; unmarked wormy column and dark longitudinal lines marking mesenterial insertions. Right: contracted tenetacles; 16 opaque white tapered areas mark intermesenterial spaces.

Figure 5: Left: specimen freshly removed from sediment; unmarked wormy column and dark longitudinal lines marking mesenterial insertions. Right: contracted tenetacles; 16 opaque white tapered areas mark intermesenterial spaces.Photograph by Ria Tan.[12]

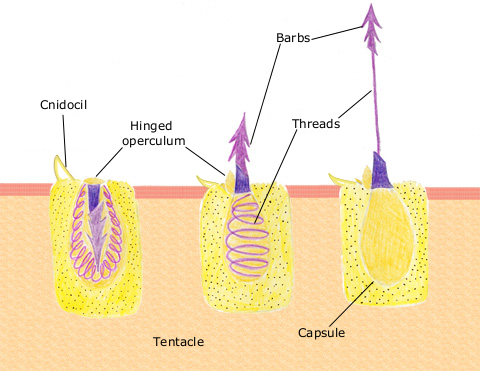

Their tentacles are loaded with stinging cells also known as nematocysts. This feature is a common trait among the Cnidarians such as corals, jellyfish and hydra. Each nematocyst contains a small vesicle which contains an organelle called a cnidae and an external sensory hair. When the hair is triggered, the cnidae inverts outward to inject neurotoxins with a harpoon-like structure that penetrates the target organism. After the discharge, the paralysed prey is then devoured by the cnidarian.

Figure 6: Discharged mechanism of the nematocyst.Picture taken by Spaully [13]

Life History

In sea anemones, both sexual and asexual reproduction have been observed. In asexual reproduction, the sea anemone breaks into smaller pieces that regenerate into polyps, whereas sexual reproduction occurs when the polyp produces eggs and sperm.The fertilised egg develops into a planula larva, a free-swimming organism with a flattened, ciliated, solid body. The ciliated planula larva further develops into another polyp as illustrated in the figure below. For Metapeachia tropica, Panikkar observed that the type specimen's gonads (an organ that produce sex cells) are borne by all the mesenteries, indicating that the specimen was a male with well-developed testes. This add strength to the hypothesis that it is able to reproduce sexually.

In his study, Panikkar observed that the larvae of M. tropicaare parasitize on Aquorea pensile, a common jellyfish found in the subclass of Hydromedusae. The larvae attach themselves to the sub-umbrellar surface of the jellyfish between the margin and the mouth with their oral disc. Before falling off the jellyfish, the disc-shaped individuals assume an elongated conical column. There are three distinct groups of growth stages observed: 4-6 Mesentery Stages, Eight-Mesentery Stages and 12-Mesentery Stages. [15] The last four tentacles only develop after the larvae have settled on the bottom. This period of parasitism typically occurs from November to March. One hypothesis of such behaviour could be that the larvae gain protection from the jellyfish since the stinging cells of the jellyfish deter any unwanted predators.

Species Interactions

Beside the clownfish (Fig. 9), sea anemones do form symbiotic relationship with several other species of fish, invertebrates and even algae. Most symbiotic relationships are sustained because sea anemones protect symbionts from predators with their stinging cells, whereas the symbiont provides nutrients or food for the sea anemone in return.

Taxonomy

===Rank and Taxa names [18]| Kingdom |

Animalia |

| Phylum |

Cnidaria |

| Class |

Anthozoa |

| Subclass |

Hexacorallia |

| Order |

Actiniaria |

| Suborder |

Enthemonae |

| Superfamily |

Actinioidea |

| Family |

Haloclavidae |

| Genus |

Metapeachia |

| Species |

Metapeachia tropica |

"The anemone is long and vermiform, about 30 mm. long and 9 mm. wide at the broadest part in the expanded condition. The column is whitish-yellow in colour, with splashes of reddish-brown markings at the bases of the tentacles. The markings on the tentacles together form a joint pattern as in Peachia hastata (Stephenson, 1928). Each tentacle is usually barred four times, each bar consisting of a pair of marks. In addition to this, the tentacles bear dark spots at their extremities."

While Panikkar did recognize Metapeachia tropica anemone to be different from other Peachia anemone, he still classified it under the same genus. Its diagnosis was later revised by Carlgren in 1943 due to the number of tentacles, 16 for Metapeachia and 12 for Peachia, even though it has a similar conchula as other Peachia anemones.

SynonymsPeachia sp. Menon, 1927:35.

Peachia tropica Panikkar, 1938:182–193, 200–201 (original description).

Metapeachia tropica: Carlgren, 1943:22, 1949:31.—Parulekar, 1966:40, 1968:141, 143.—Haque, 1977:35, 38.—Grebelny, 1982:107.—England, 1987:207 [Panikkar publication dated 1939].—Parulekar, 1990:220, 223, 224.—Goswami, 1992:118.—Mitra, 2010:136.

Type InformationThere is currently no type specimen for Metapeachia tropica. Voucher specimens have been found in the museums of the Bombay Natural History Society, the Zoological Survey of India, the University of Madras, Department of Zoology. A 'voucher specimen' is any specimen that serves as a basis of study and is retained as a reference, however it is not the type specimen. Reportedly, the holotype was found to be 30mm long while the voucher specimens in the museum were stated to be 16mm.

Phylogeny

Boundaries in sea anemones are clear to distinguish it from the other cnidiarian counterparts; however not the same could be said for its subclass and orders. Classification of sea anemones is a complex issue as most studies follow the morphological species concept where species are characterised by their body shape and other structural features. This practice of characterisation is used as members of the anthozoan subclass Hexacorallia exhibit great variation in anatomy, biology and life history. However this isn't always applicable as most relationships among Actinarian are based on absence of features rather than their synapomorphies. Synapomorphy refers to a characteristic trait present in an ancestral species and shared exclusively by all its evolutionary descendants.The morphological concept is still being applied as details of their gene flow are relatively unknown. The conservative nature of sea anemone genes and their slow molecular evolution as compared to other invertebrates makes it hard for scientists to determine distinct boundaries for each class.The current classification of Actiniaria was codified by Calgren in 1949 in his monograph on actiniarians, corallimorpharains, and pytchodactiarians,[19] but this phylogenetic tree has also been criticised as some genetic studies have shown some families to be nested in each other. [20]

Metapeachia tropica belongs to the family of Haloclavidae[21] , the second most speciose family of burrowing anemones. Monophyly for Haloclavidae established by Verrill in 1899[22] remains unclear as the distinction between Haloclavidae and another family, Halcampoididae is not clearly established, because none of the attributes found in Halcampoididae are unique to the group.[23] [24] Members of this family has a distinct siphonoglyph (a ciliated groove at one or both ends of the mouth of sea anemones) that is raised above the oral disc into a unique structure called the conchula (Fig 10).

Metapeachia tropica was considered the only species of its genus till a recent study published by Lucianna C. Gusmão where another species, Metapeachia schlenzae sp. was described and recognised as another species of this genus.[26]

Figure 11: Diagram taken from Phylogenetic relationships among sea anemones (Cnidaria: Anthozoa: Actiniaria) [27]

The phylogenetic tree above shows the phylogenetic relationships among sea anemones. While it was erected out of the Peachia genus in 1943 by Calgren using morphological differences, understanding the phylogenetic relationship of Peachia genus is still important as phylogenetic analysis of the Metapeachia genus is still unknown. This tree was constructed using two mitochondrial markers (partial 16S and 12S rDNA) and two nuclear markers (18S and partial 28S rDNA) from 45 genera in 23 families. Strict consensus tree of five primary trees resulting from combined parsimony shows a polyphyletic Athenaria, with the three members of the athenarian family Edwardsiidae basal to a clade consisting of Boloceroidaria, Thenaria, and the remaining Athenaria.

Species diagnosis toolDNA sequences for each marker were aligned in the software MUSCLE using the default parameters. [28] Incongruence Length Difference test was used to identify any instances of incongruence within and between the nuclear and mitochondrial markers. [29] The resulting alignments were analysed separately and in combination using parsimony using random and consensus sectorial searches [30] . In all analyses, gaps were treated as ambiguous state coded as ? character rather than as fifth state element. Ultimately, molecular phylogenetic studies have demonstrated that Carlgren’s classification is flawed as a phylogenetic hypothesis, but the precise nature of the conflict between phylogeny and classification is not clear.

The lack of correspondence between taxonomy and ecological, morphological, or biological variables will hinder future studies of sea anemones. For example, some ecologically important variables like ability to engage in aggressive intraspecific interactions were found to correspond to historical hypotheses of relatedness [31] , but other features, including reproductive mode or symbiotic state, seem not to follow a consistent pattern. Hence, it is vital to find a working phylogenetic framework so that studies of the evolution and diversification of anemones can advance.

References

- ^ https://www.flickr.com/photos/wildsingapore/5720768583

- ^ GeninSider. (2007) Finding Nemo : Amnemonemomne. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bZ1KDf3O-qU

- ^ http://www.wildsingapore.com/wildfacts/cnidaria/actiniaria/boloceroididae.htm

- ^ Waymire5. (2013) Swimming anemone. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-6lMD9h_ix4&t=40s

- ^ Rodríguez, E., & López-González, P. J. (2003). Stephanthus antarcticus, a new genus and species of sea anemone (Actiniaria, Haloclavidae) from the South Shetland Islands, Antarctica. Helgoland Marine Research, 57(1), 54.

- ^ Ian Stevenson, (2012) Burrowing sea anemone. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GDb0MRRvE-I

- ^ http://hercules.kgs.ku.edu/Hexacoral/Anemone2/

- ^ Yap, N. W., Fautin, D. G., Ramos, D. A., & Tan, R. (2014). Sea anemones of Singapore:Synpeachia temasek new genus, new species, and redescription of Metapeachia tropica(Cnidaria: Actiniaria: Haloclavidae). Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington, 127(3), 439-454. doi:10.2988/0006-324x-127.3.439

- ^ Yap, N. W., Fautin, D. G., Ramos, D. A., & Tan, R. (2014). Sea anemones of Singapore:Synpeachia temasek new genus, new species, and redescription of Metapeachia tropica(Cnidaria: Actiniaria: Haloclavidae). Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington, 127(3), 439-454. doi:10.2988/0006-324x-127.3.439

- ^ http://www.wildsingapore.com/wildfacts/cnidaria/actiniaria/synpeachia.htm

- ^ https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Anemone_anatomy.svg

- ^ http://www.wildsingapore.com/wildfacts/cnidaria/actiniaria/peachia.htm

- ^ https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Nematocyst_discharge.png

- ^ Ricah Shah. Metridium: Histology, Digestion and Reproduction. http://www.biologydiscussion.com/invertebrate-zoology/sea-anemone/metridium-histology-digestion-and-reproduction/28693

- ^ Panikkar, N. K. 1938. Studies on Peachia from Madras. Proceedings of the Indian Academy of Sciences, Section B, 7(4):182–205.

- ^ https://www.aquablog.ca/2013/05/hitchhiking-crab/resize-peachia-quinquecapitata-on-mitrocoma-cellularia_5323_dannykent-29jul10/

- ^ Ratha Grimes (2014). Anemonefish https://www.flickr.com/photos/ratha/15349382184/in/photolist-qkbKkH-ponAyq

- ^ http://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=290344

- ^ Carlgren, O. (1943). East-Asiatic Corallimorpharia and Actiniaria. Stockholm: Almqvist.

- ^ Geller, J. B., & Walton, E. D. (2001). Breaking up and getting together: evolution of symbiosis and cloning by fission in sea anemones (genus Anthopleura). Evolution, 55(9), 1781-1794.

- ^ Daly, M., Brugler, M. R., Cartwright, P., Collins, A. G., Dawson, M. N., Fautin, D. G., France, S. C., Mcfadden, C. S., Opresko, D. M., Rodriguez, E., Romano, S. L. & Stake, J, L. (2007). The phylum Cnidaria: a review of phylogenetic patterns and diversity 300 years after Linnaeus.

- ^ Verrill, A. E. (1899). Descriptions of imperfectly known and new actinians, with critical notes on other species, II. American Journal of Science, Fourth Series, 7(37):41–50.

- ^ Daly, M., Fautin, D.G. & Cappola, V.A. (2003) Systematics of the Hexacorallia (Cnidaria: Anthozoa). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 139, 419–437.

- ^ Berntson, E.A., France, S.C. & Mullineaux, L.S. (1999) Phylogenetic relationships within the Class Anthozoa (Phylum Cnidaria) based on nuclear 18S rDNA sequences. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 13, 417–433.

- ^ http://wildshores.blogspot.sg/2011/07/special-anemone-find-at-sentosa.html

- ^ Gusmão, L. C. (2016). Metapeachia schlenzae sp. nov. (Cnidaria: Actiniaria: Haloclavidae) a new burrowing sea anemone from Brazil, with a discussion of the genus Metapeachia . Zootaxa, 4072(3), 373. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.4072.3.6

- ^ Daly, M., Chaudhuri, A., Gusmão, L., & Rodriguez, E. (2008). Phylogenetic relationships among sea anemones (Cnidaria: Anthozoa: Actiniaria). Molecular phylogenetics and evolution, 48(1), 292-301.

- ^ Edgar, R. C. (2004). MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic acids research, 32(5), 1792-1797.

- ^ Farris, J. S., Källersjö, M., Kluge, A. G., & Bult, C. (1994). Testing significance of incongruence. Cladistics, 10(3), 315-319.

- ^ Goloboff, P. A., Farris, S., & Nixon, K. (2003). Tree Analysis using New Technology. Published by the authors, Tucumán

- ^ Francis, L. (1988). Cloning and aggression among sea anemones (Coelenterata: Actiniaria) of the rocky shore. The Biological Bulletin, 174(3), 241-253.