|

Name

Binomial: Suncus murinus (Linnaeus, 1766)Synonyms: Up to 59 synonyms are listed by Hutterer (2005) due to its high phenotypic plasticity.

Vernacular: Asian House Shrew

Alternatives: House Shrew, Asian Musk Shrew, Indian Musk Shrew, Brown Musk Shrew...[more common names]

Etymology

The word “shrew” was originally coined to refer to a small mammal. The Old English form of the word was “screawa” or “shrew-mouse”. The other meaning of “shrew” as a "spiteful person" came from the Middle English form “shrewe”, referring to an “evil or scolding person”, arose from then negative perception of the animal, which was believed to have a venomous bite. This was later discovered to be true in some species of shrews. The Asian House Shrew was named as it is commonly found living alongside human habitations (houses) in Asia.ref: Schmidt, 1994

Diagnosis

Asian House Shrews and Brown Rats (Rattus norvegicus) are both commonly found in Singapore's urban areas, but Asian House Shrews are often mistaken as rats. An Asian House Shrew can generally be differentiated from a rat by its pointed snout, shorter thicker tail and smaller eyes as seen in the pictures below:ref: Wildlife Singapore, 2006

| Left: Photo by Ria Tan, www.wildsingapore.per.sg. Right: Photo by JC Shou, www.biopix.com |

Asian House Shrews can also be distinguished from the only other species of shrew in Singapore, the Malayan White-toothed Shrew (Crocidura malayana), by the bigger size of the former. The Malayan White-tooth Shrew is rare and is restricted to the forests of Bukit Timah Nature Reserve and Central Catachment Nature Reserve.

ref: Chua & Lim, 2011

Among the shrew family, the Asian House Shrew is the largest species of shrews. It can be differentiated from its closest relative, the Asian Highland Shrew (Suncus montanus) by its bigger size, thicker tail and lighter pelage, both dorsal and ventral.

ref: Meegaskumbura et al., 2010

Geographic Range

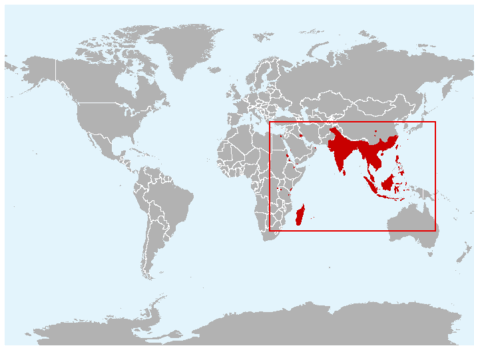

Contrary to popular notion, this species is not native to Singapore, but is an introduced species. The Asian House Shrew is believed to have originated in the forest of central India. With the help of early human transportation both on land and sea, this species then dispersed to surrounding areas, including Africa, Middle East, Southeast Asia and Japan.ref: Ellerman, 1961; cited in Meegaskumbura et al., 2010; Global Invasive Species Database, 2006; Corlett, 1992

|

| Red areas show where Asian House Shrews can be found today. Citation: Hutterer, R., S. Molur & L. Heaney, 2008. Suncus murinus. In: IUCN 2011. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2011.1. <www.iucnredlist.org>. Downloaded on 03 November 2011. |

Description

In general, the body colour, size and chromosome number varies between localities (between different populations at different areas).Adults

Colour: Light grey in Sri Lanka, grey in Bangladesh, to dark grey in almost all areas of Asia

Length: Head + Body up to 15 cm; tail up to 9.5 cm

Face: Small eyes, long pointy snout with conical sharp teeth, long jaws containing rows of pointed teeth

Tail: Thick at the base and hairy

Weight of females: 23.5 g to 82.0 g

Weight of males: 33.2 g to 147.3 g

Sexual dimorphism: Males generally larger than females and having well-developed scent glands on the sides of its body (in females this is variable)

Chromosome number: Generally 2n = 40; but can range from 2n = 30 or 32 in South India and Sri Lanka to 2n = 35 to 40 in the Malay Peninsula

ref: Chua & Lim, 2011; Kurachi et al. and references therein, 2007; Ruedi et al. and references therein, 1996.

|

|

Young

Average litter size: 1.84 g

Average weight of young females: 2.0 g

Average weight of young males: 2.3 g

Hair: Few guard hairs and well-developed whiskers present when born; underfur develops at day 4, complete fur development by day 10

Eyes: Closed eyelids with pink irises at birth, irises turn black at day 2 and eyes open between days 7 to 10

Incisors: Full development between days 6 to 14

Independency: Self-sufficient by day 20

ref: Dryden, 1968

|

| A 2 day old Asian House Shrew. Photo by W.A Djatmiko, Wikipedia Commons |

More information on the anatomy of Suncus murinus is detailed in Sharma, 1958.

Biology

Habitat

Asian House Shrews are commonly found in human habitations, including urban areas. They can also be found in the forest.

ref: Global Invasive Species Database, 2006

Life expectancy

They can live for 1.5 to 2 years in captivity and 1 to 2 years in the wild.

ref: Schmidt, 1994; Dryden, 1969

Feeding habits

Asian House Shrews are insectivores and eat mainly a wide range of insects. They are also opportunistic feeders and feed on variety of other food items such as plant material, a wide variety of invertebrates such as cockroaches, as well as discarded food items. The Asian House Shrew has a high metabolic rate and are nocturnal and hence requires multiple feeding periods throughout the night.

ref: Chua & Lim, 2011; Balakrishnan & Alexander, 1979

Reproduction

The mating system of the Asian House Shrew is unknown. Sexual dimorphism in sizes suggest that they may be polygynous, however as both sexes are known to collect nesting material before the female gives birth, it is suggested that they may be monogamous.

Reproduction occurs throughout the year, peaking during spring and summer. Female Asian House Shrews reach sexual maturity at 35 days old and do not have a behavioral estrus cycle; the process of mating will induce the development of the follicles and start of ovulation. The sperm will spend a long time in the female's reproductive tract before fertilizing the egg.

Nests are constructed in hidden areas called snags using any available resources such as leaves and other loose materials.

Gestation period usually lasts for 30 days. Two litters of 4 to 8 young (usually 3) may be born in one year. The young are weaned at 15 to 20 days old. The young stay in the nest until they are about 75% grown. Should they travel out of the nest however, the young will travel in a convey train with the mother, each clamping its jaws tightly to the rear or base of the tail of the preceding shrew. This caravaning behavior is reported to appear only in very young shrews, initially for the mother to retrieve her straying young back to the safety of the nest. Later on, when the young's eyes are opened, caravaning serves as an environmental exploration.

ref: Global Invasive Species Database, 2006; Nowak, 1999; Muhammad et al., 1999; Tsuji, 1984

|

Defense mechanism

Asian House Shrews have been reported to emit a musky odor to deter predators. The musky odor also discourages other males from following, allowing even distribution of the Asian house shrew population. This musky odor is secreted by the sweat glands on its throat and behind the ears which may also be trapped by the oily secretions of the specialized sebaceous tubules localized in the sideglands to make the odor last. This musky odor also contributes to its alternative common name, Asian Musk Shrew.

ref: Dryden, 1967

Sound

It emits a variety of chirps, buzzes or shrill squeaks which may be associated with aggressive behavior. The constant small chattering noises it makes resembles the jingling of coins, and hence is also named as the Money Shrew in China.

ref: Chua & Lim, 2011; Burton & Burton, 2002; Nowak, 1999

Conservation status

Owing to its wide distribution and presumed large population, the Asian House Shrew is classified as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List.

ref: Hutterer et al, 2008

Ecological/Economic contributions

Negative

Due to its high reproductive rate and low predation risk, Asian House Shrews are a growing ecological threat to many plant and animal species and are considered an invasive species in some countries. Their ability to survive in high densities near human habitations, while damaging foods and other materials has also resulted in them being labelled as pests in some areas. More studies on the management of this species in urban environments are required.

ref: Global Invasive Species Database, 2006

Positive

Being insectivores, Asian House Shrews predate on many insect pest species, such as cockroaches, hence helping to control their population. Asian House Shrews have also been successfully domesticated as a laboratory animal in USA and Japan and is a model species in medicinal, physiology, behavioral and psychology-related research fields.

ref: Global Invasive Species Database, 2006; Tsuji, 1999

In our homes - problems and management

In Singapore, Asian House Shrews are not considered pests, unlike the following commonly-found rodents: Brown Rat (Rattus norvegicus), Roof Rat (Rattus rattus) and House Mice (Mus musculus). Asian House Shrews however may be a disturbance for its strong and unpleasant musky odor or its incessant loud squeaks. They may also destroy stored grain products. Asian House Shrews may also harbor rodent-borne viruses such as leptospirosis but potential for transmission to humans has been poorly documented and probably much lower compared to rats.

Installation of rodent proof structures can exclude shrews, as well as regular mowing of the lawn which decreases their preferred habitat and food(insect) availability. Presence of cats may also reduce their densities, although they seldom eat them. Asian House Shrews can be trapped with mouse traps baited with a mixture of peanut butter and rolled oats. More information on the management of this species can be found here.

ref: Rahelinirina, 2010; Global Invasive Species Database, 2006; Schmidt, 1994 and references therein

Warning!

The following sections on taxonomy and phylogenetics of the Asian House Shrew may not make for an easy reading, especially if you do not come from a scientific background. Feel free to skip the following sections to the commenting box if you like, or if you feel brave, do read on and gain new knowledge! Brief explanations of each sections are provided in italics. However, it is recommended that you Google or Wiki up any unfamiliar terms.

The following sections would be useful to anyone (with biological knowledge) interested in understanding or researching about the biological history of the Asian House Shrew. In knowing about its taxonomy and phylogenetic history, we would then understand the story of how Asian House Shrews came about today.

Taxonagivation

Every living-thing on Earth has a name, and is classified systematically into different hierarchical ranks. The following shows the biological classification of the Asian House Shrew.Kingdom: Animalia (animals)

- Phylum:Chordata (chordates)

- Subphylum:Vertebrata (vertebrates)

- Class:Mammalia (mammals) ....................................................................................................[Linnaeus, 1758]

- Subclass:Theria .............................................................................................................[Parker and Haswell, 1897]

- Infraclass:Eutheria ...............................................................................................[Gill, 1872]

- Order:Soricomorpha (solendonts, shrews, moles, …) .....................................[Gregory, 1910]

- Family:Soricidae (shrews) ..................................................................[G. Fisher, 1814]

- Subfamily:Crocidurinae (white-toothed shrews) ..........................[Milne-Edwards, 1872]

- Genus:Suncus (white-toothed shrews) ..............................[Ehrenberg, 1832]

- Species: Suncus murinus (Asian house shrew) .......[Linnaeus, 1766]

- Genus:Suncus (white-toothed shrews) ..............................[Ehrenberg, 1832]

- Subfamily:Crocidurinae (white-toothed shrews) ..........................[Milne-Edwards, 1872]

- Family:Soricidae (shrews) ..................................................................[G. Fisher, 1814]

- Order:Soricomorpha (solendonts, shrews, moles, …) .....................................[Gregory, 1910]

- Infraclass:Eutheria ...............................................................................................[Gill, 1872]

- Subclass:Theria .............................................................................................................[Parker and Haswell, 1897]

- Class:Mammalia (mammals) ....................................................................................................[Linnaeus, 1758]

- Subphylum:Vertebrata (vertebrates)

(Retrieved on 15 October 2011 from the Integrated Taxonomic Information System on-line database)

Subspecies - Past and Present

A species can be further differentiated into subspecies, as summarized here for the Asian House Shrew.Due to its wide morphological variation in body size and tail length, individual populations of Asian House Shrews were classified into different subspecies or races by early mammalogists. Today, most of these subspecies classification have been disregarded as it is currently not possible to have a clear allocation of all listed taxa to subspecies. In 2010, two populations of Suncus murinus in Sri Lanka (S. m. murinus and S. m. kandianus) were identified as putative hybrids of Suncus murinus and Suncus montanus, the closest relative of Suncus murinus. However, additional gene comparison studies are required to evaluate the extent of hybridization.

ref: Meegaskumbura et al., 2010; Hutterer, 2005

Type Information

Original type descriptions and locality show who first found the organism at where and gave it a name. Specimens collected are then stored at museums so that it will be useful for taxonomists to compare with later collections to confirm that they are of the same species.Original Type Description

First described by Linnaeus as Sorex murinus. Original description by Linnaeus can be found here:

Linnaeus, C. 1766. Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis synonymis, locis (12th Edition). Vol. 1: Regnum Animale, Part 1. Laurentii Salvii, Stockholm. 74. Available online here.

Type Locality

Java, Indonesia.

Suncus murinus is a type species of Genus Suncus

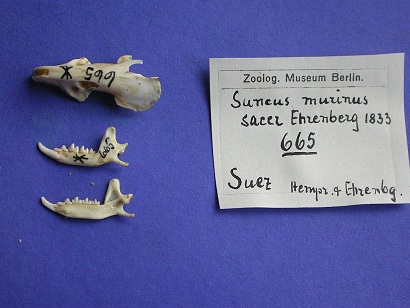

Suncus murinus sacer (Ehrenberg, 1832) was described to be the type species of the Genus Suncus. Suncus murinus sacer today is classified as a subspecies of Suncus murinus; therefore Suncus murinus is now considered as a type species of the Genus Suncus.

The specimen collected by Ehrenberg can be found in the Museum für Naturkunde, Berlin, where Ehrenberg's collections are stored. Its images are as shown:

|

|

ID: ZMB - 665 Individuals: 1 Collectors: Hemprich, Ehrenberg Date of collection: 1833 Locality: Suez, Egypt ref: Systax Photos: Copyright pending. |

A specimen was collected in Singapore in 1940 and is displayed at the Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research (RMBR) .

|

| Specimen at RMBR. Photo by Ivan Kwan. lazy-lizard-tales.blogspot.com |

Phylogeny

The phylogeny of the Asian House Shrew is important as from it we can then understand the evolutionary relationships of the Asian House Shrew.The following two pictures show the phylogenetic relationships between the Asian House Shrews and other shrew species, and the relationships between Asian House Shrews in different geographical locations respectively.

| A simplified representation of the phylogenetic tree of the genus Suncus. Only some species are shown here. Note that the Asian Highland Shrew is the sister taxon of the Asian House Shrew (highlighted). This phylogenetic tree was modified from Figure 2A of the following paper: Omar, H., E. A. S. Adamson, S. Bhassu, S. M. Goodman, V. Soarimalala, R. Hashim & M. Ruedi, 2011. Phylogenetic relationships of Malayan and Malagasy pygmy shrews of the Genus Suncus (Soricomorpha: Soricidae) inferred from mitochondrial cytochrome B gene sequences. Raffles Bulletin of Zoology 59(2): 237-243 |

|

| The relationship among 17 wild Asian House Shrew populations from various locations as indicated in the tree. These populations can be divided into two groups, a South Asian group and a Southeast Asian group as shown by the solid black and open bars. The textured bars within the Southeast Asian group indicate the clusters that are closely linked by genetic and geographic relationships. Although a sample from Singapore was not included in the analysis, Asian House Shrews in Singapore is most likely closely related to the Asian House Shrews in Malaysia due to close proximity between the two countries. This image was taken from Figure 2 of the following paper: Kurachi, M., Y. Kawamoto, Y. Tsubota, B. Chau, V. Dang, T. Dorji, Y, Yamamoto, M. M. Nyunt, Y. Maeda, L. Chhum-Phith, T. Namikawa & T. Yamagata., 2007. Phylogeography of wild musk shrew (Suncus murinus) populations in Asian based on blood protein/enzyme variation. Biochem Genet 45: 543-563 |

Comments

If you would like to comment on anything related to this webpage e.g. mistakes spotted, provide more information, etc, do feel free raise your views in the discussion box below:| Subject | Author | Replies | Views | Last Message |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Comments | ||||

Literature and References

- Balakrishnan, M. & K. M. Alexander, 1979. Effect of fasting on aspects of feeding on the Indian musk shrew, Suncus murinus viridescens (Blyth). Proc. Indian Acad. Sci. 88(I3): 178-185.

- Burton, M. & R. Burton, 2002. Musk Shrews. In: The international wildlife encyclopedia (3rd Edition). Marshell Cavendish Corporation. 1709-1710. Available online here. (Accessed 14 October 2011)

- Chua, A. H. M. & K. P. K. Lim, 2011. Shrews. In: Ng, P. K. L., R. T. Corlett & H. T. W. Tan (eds.), Singapore biodiversity: an encyclopedia of the natural environment and sustainable development. Editions Didier Millet. Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research, Singapore. 456.

- Corlett, R. T., 1992. The ecological transformation of Singapore, 1989-1990. Journal of Biogeography 19(4): 411-420.

- Dryden, G. L., 1968. Growth and development of Suncus murinus in captivity on Guam. Journal of Mammalogy 49(1): 51-62.

- Dubey, S., N. Salamin, S. D. Ohdachi, P. Barriere & P. Vogel, 2007. Molecular phylogenetics of shrews (Mammalia: Soricidae) reveal timing of transcontinental colonizations. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 44: 126-137.

- Global Invasive Species Database (GISD), 2006. "Suncus murinus" Available online here. (Accessed 15 October 2010)

- Hemprich, W. & C. G. Ehrenberg, 1833. Symbolae Physicae. 5.

- Hutterer, R., 2005. Order: Soricomorpha. In: Wilson D. E. & D. M. Reeder (eds.), Mammal species of the world: a taxonomic and geographic reference (3rd Edition). John Hopkins University Press. Available online here. (Accessed 27 October 2011)

- Hutterer, R., S. Molur & L. Heaney, 2008. Suncus murinus. In: IUCN 2011. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2011.2. Available online here. (Accessed 17 November 2011)

- Kurachi, M., Y. Kawamoto, Y. Tsubota, B. Chau, V. Dang, T. Dorji, Y, Yamamoto, M. M. Nyunt, Y. Maeda, L. Chhum-Phith, T. Namikawa & T. Yamagata., 2007. Phylogeography of wild musk shrew (Suncus murinus) populations in Asian based on blood protein/enzyme variation. Biochem Genet 45: 543-563

- Linnaeus, C. 1766. Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis synonymis, locis (12th Edition). Vol. 1: Regnum Animale, Part 1. Laurentii Salvii, Stockholm. 74. Available online here. (Accessed 17 October 2010)

- Major Flower, S. S., 1932. The recent mammals of Egypt, with a list of the species recorded from that kingdom. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 102(2): 375-376.

- Meegaskumbura, S., M. Meegaskumbura & C. J. Schneider, 2010. Systematic relationships and taxonomy of Suncus montanus and S. murinus from Sri Lanka. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 55: 473-487.

- Muhammad, M. U. H., B. M. Azhar, K. A. Ali & M. U. H. Muhammad, 1999. Small mammals inhibiting village households and farmhouses of Central Punjab. Pakistan Journal of Zoology 30: 207-211.

- Nowak, R. 1999. Walker's Mammals of the World, Sixth Edition. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Omar, H., E. A. S. Adamson, S. Bhassu, S. M. Goodman, V. Soarimalala, R. Hashim & M. Ruedi, 2011. Phylogenetic relationships of Malayan and Malagasy pygmy shrews of the Genus Suncus (Soricomorpha: Soricidae) inferred from mitochondrial cytochrome B gene sequences. Raffles Bulletin of Zoology 59(2): 237-243

- Rahelinirina, S, A. Leon, R. A. Harstskeerl, N. Sertour, A. Ahmed, C. Raharimanana, E. Ferquel, M. Garnier, L. Chartier, J-M. Duplantier, L. Rahalison & M. Cornet, 2010. First isolation and direct evidence for the existence of large small-mammal reservoirs of Leptospira sp. in Madagascar. PLoS One 5(11): e14111. Available online here. (Accessed 8 November 2011)

- Reudi, M., C. Courvoisier & P. Vogel, 1996. Genetic differentiation and zoogeography of Asian Suncus murinus (Mammalia: Soricidae). Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 57: 307-316.

- Schmidt, R. H., 1994. Shrews. In: Hygnstrom, S. E., R. M. Timm & G. E. Larson (eds.), Prevention and Control of Wildlife Damage. University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Nebraska. 87-91. Available online here. (Accessed 8 October 2011)

- Sharma, D. R., 1958. Studies on the anatomy of the Indian insectivore, Suncus murinus. Journal of Morphology 102(3): 427-553.

- Tsuji K., T. Ishikawa, 1984. Some observations of the caravaning behavior in the musk shrew (Suncus murinus). Behavior 90(1/3): 167-183.

- Tsuji K., K. Ishii, T. Matsuo & K. Kawano, 1999. The house musk shrew Suncus murinus as a new laboratory animal for use in behavioral studies. Japanese Journal of Animal Psychology, 49: 1-18.

- Wildlife Singapore, 2006. House Shrew - Suncus murinus. Wildlife Singapore website. Available online here. (Accessed 15 October 2011)

Other Species Pages

Animal Diversity Web (//Suncus murinus//)Encyclopedia of Life (//Suncus murinus//)

Invasive Species Specialist Groups - ISSG (//Suncus murinus//)