Asian Paradise-flycatcher

Terpsiphone paradisi (Linnaeus, 1758)*The Asian Paradise-flycatcher will be treated as a single species here despite the recent split adopted by certain treatments.

Table of Contents

|

| Photograph by Thimindu Goonatilike (2010), licensed under Creative Commons. Annotations by Dominic Ng. |

With over ten thousand species by most accounts, the birds (Aves) make up the most diverse vertebrate group after 'fishes'. About four hundred species have been recorded in tiny Singapore, an incredible number in light of its overall land area!

Birds are charismatic, and arguably the easiest to observe in nature compared to other vertebrate taxa in Singapore. It is not at all unusual here to sight dozens of bird species in the space of a few hours! Many of these species tend to be very visually distinct, making the learning curve for identification relatively shallow. The sheer variety in colour and form of the numerous bird species here can be easily appreciated by a wide, general audience, and can serve as a platform to developing a greater interest and love for nature and wildlife.

The Asian Paradise-flycatcher is one of the more charismatic species with records in Singapore. The species is relatively common, with the two native subspecies observed in a variety of forms, making it easy to see and rewarding for both beginners and more enthusiastic birders alike. It can be seen in most 'green areas' here, often along forest edges and deeper in, but can sometimes be observed in parks and gardens!

In addition, more detailed information on taxonomy and systematics of this species, and indeed the family as a whole, are difficult to pin down in a single location, often requiring journal access and volumes, the existence of which is likely unfamiliar to many. This page aims to condense and make available such resources in a single location.

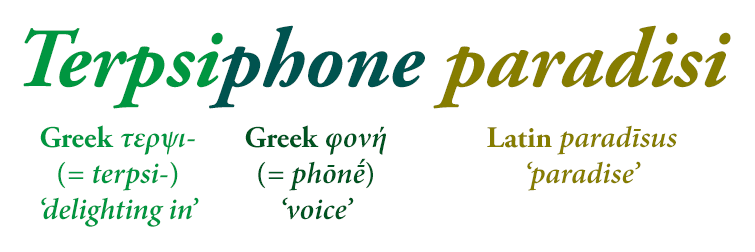

Etymology

The generic epithet Terpsiphone is derived from Greek τερψι-, terpsi-, 'delighting in', and φωνή, phōnē, 'voice'; the specific epithet paradisi is derived from Late Latin paradīsus, 'paradise'[1] .

Diagnosis

|

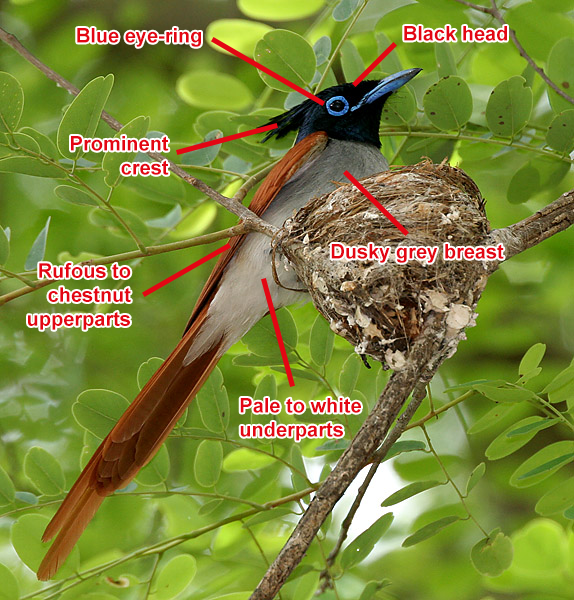

| Photograph by J. M. Garg (2009), licensed under Creative Commons. Annotations by Dominic Ng. |

The Asian Paradise-flycatcher, having an average body length of 20 cm, is unmistakable, with its rufous to chestnut upperparts, pale to white underparts, grey breast, black head with a prominent crest, and blue eye-ring. It cannot be confused with anything else in the region except the much rarer, migratory Japanese Paradise-flycatcher (T. atrocaudata) - the male of the latter has purple to black upperparts, while the female is extremely difficult to discern in the field. The males of both species have long tail streamers that are often longer than the body itself[2] .

|

| Photograph by Francis Yap (2016), permission granted. Annotations by Dominic Ng. |

Description

The Asian Paradise-flycatcher exhibits sexual dimorphism, with the male's distinctive tail streamers a prominent feature. The male additionally exhibits dichromatism, with a rufous morph and a white morph; the female only exists in the rufous morph. The spotting present in the juvenile plumage is lost upon maturity. |

| Left to right: Photographs by Som Bhattacharya (2009), Dr Raju Kasambe (2013), Lip Kee Yap (2011), licensed under Creative Commons. Annotations by Dominic Ng. |

Two subspecies are recorded in Singapore - the Oriental (=Blyth's) Paradise-flycatcher an uncommon non-breeding visitor, and the Amur Paradise-flycatcher a common winter visitor and passage migrant. The easiest way to tell both subspecies apart is by the plumage on the head and the chest - the black head sharply contrasts the pale grey chest of the Amur Paradise-flycatcher, whereas the Oriental Paradise-flycatcher shows no such contrast, appearing instead to blend together. The former also tends to have upperparts with a purple tinge, while the latter tends to have an orange tinge, but this may be difficult to ascertain in the field.

Habitat and Distribution

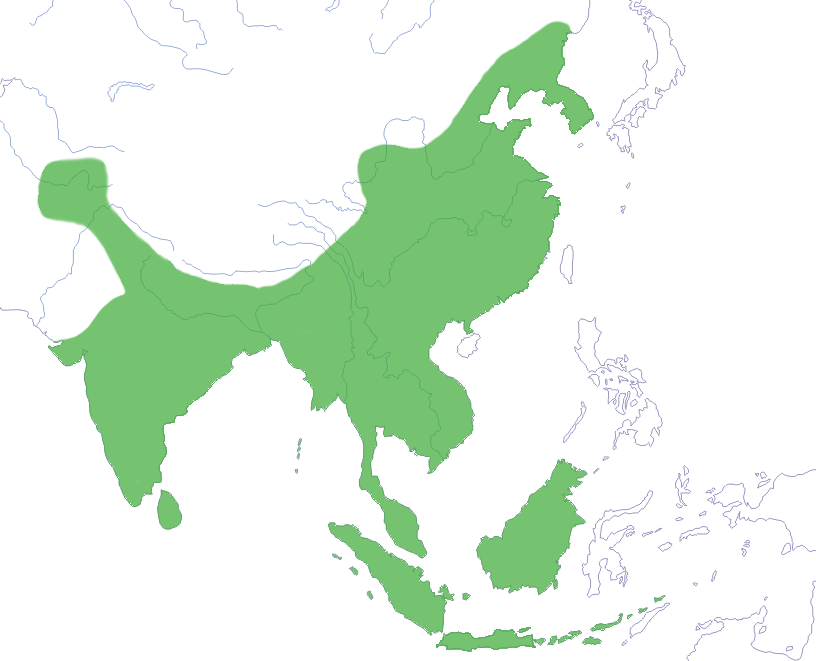

|

| Approximate distribution of the Asian Paradise-flycatcher. Figure adapted from Moeliker (2016). |

In Southeast Asia and indeed, throughout Singapore, the Asian Paradise-flycatcher is present in broadleaf evergreen forest, secondary growth, mangrove, and even parks and garden for birds on migration.

Biology

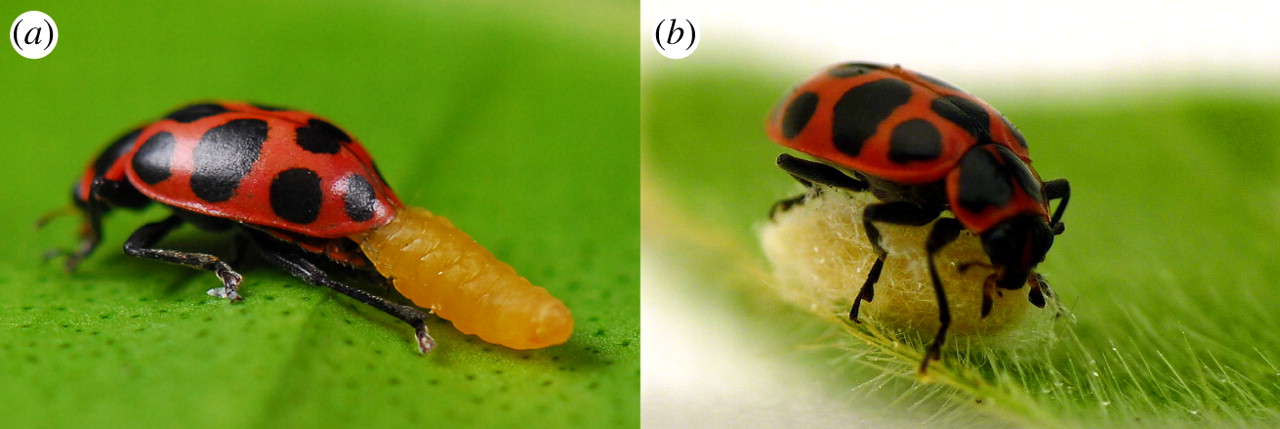

Diet and Feeding

The Asian Paradise-flycatcher primarily consumes small winged insects such as flies, bugs and beetles, but is known to occasionally feed on spiders as well as larger insects, such as praying mantises, moths, and butterflies, by battering them to death and consuming the thorax and abdomen. It usually perches high on a shade-covered branch,sallying out to catch insects on the wing and returning to the perch to consume them - often singly or in pairs[3] .

Breeding

The breeding season for the non-migratory subspecies affinis is March to July, while for the migratory species incei it is May to July. Males are highly territorial and do not tolerate intruders. Breeding pairs are monogamous and build the nest together but mainly by the female, who lays 3 to 4 eggs in the cup-shaped nest constructed with twigs and web[4] .Brooding duties are shared, with each parent taking turns. Incubation lasts 14 to 16 days and the nestling period 9 to 12 days, with chicks hatching in 21 to 23 days[5] .

|

| A female with her chicks. Photograph by Awais Ali Sheikh (2014), licensed under Creative Commons. |

Voice

The song (i.e. longer, more complex vocalisations used for courtship) of subspecies affinis is a monotonous, ringing, whistled 'wu-wu-wu…'; while the song of subspecies incei comprises short bouts of monotonously repeated, ringing 'ti-wu-wu-ti-wu-wu…', and is unlikely to be heard in Southeast Asia[6] . Calls (i.e. shorter, simpler vocalisations used to alert and contact flock members) tend to be harsh, rasping, or nasal.| The song of subspecies affinis, licensed under Creative Commons. |

The song of subspecies incei, licensed under Creative Commons. |

Status

The Asian Paradise-flycatcher, in spite of its beauty, is not commonly trapped, nor is it hunted, despite being common in much of its range. It is relatively robust to habitat loss, evident from its appearance in forest edges and urban green spaces. Combined with its extraordinarily widespread distribution, it is not locally nor globally threatened, and currently rated Least Concern (LC) by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN)[7] .Taxonomy and Systematics

Taxonavigation

- Animalia

- Chordata

- Aves

- Passeriformes

- Oscines

- Corvoidea

- Monarchidae

- Terpsiphone (Gloger, 1827)

- Terpsiphone paradisi (Linnaeus, 1758)

- Terpsiphone (Gloger, 1827)

- Monarchidae

- Corvoidea

- Oscines

- Passeriformes

- Aves

- Chordata

Gene sequences for ND2, COI, GAPDH, cmos, cytb, TGFb2, myoglobin, Fib5, ND3 of T. paradisi are available on GenBank. No barcode or complete genome sequence is yet available.

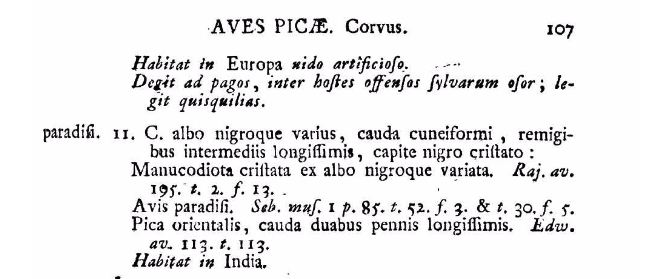

Description

The Asian Paradise-flycatcher was first described under the protonym Corvus paradisi by Linnaeus in the tenth edition of his Systema Naturæ in 1758[8] . |

| The original species description for the Asian paradise-flycatcher (Linnaeus, 1758). |

Type information

The holotype for T. paradisi is either unknown or was never designated; there exists a syntype from Flores, Bari, Indonesia; currently in the Naturalis Biodiversity Centre in Leiden, the Netherlands, dated to 1888[9] .Phylogeny

The Asian Paradise-flycatcher belongs to the suborder Oscines, placed within the most diverse avian order Passeriformes (passerines), sometimes known as 'perching birds'. The location of the oscines or 'songbirds' within the passerines is the uppermost branch of the avian tree of life (presented below), according to Jarvis et. al (2015)[10] : |

| Genome-scale phylogeny of birds, adapted from Jarvis et. al (2014). |

The monarch-flycatchers, a.k.a. monarchs (Monarchidae), is the family to which the paradise-flycatchers belong. They are now known to be closely related to crows, birds-of-paradise, and allies. Many of the hundred or so species that currently make up Monarchidae were previously assigned to other groups based on traditional systematic methods mainly favouring skeletal structure; body, leg and bill shape; and lifestyle, habits and habitat.

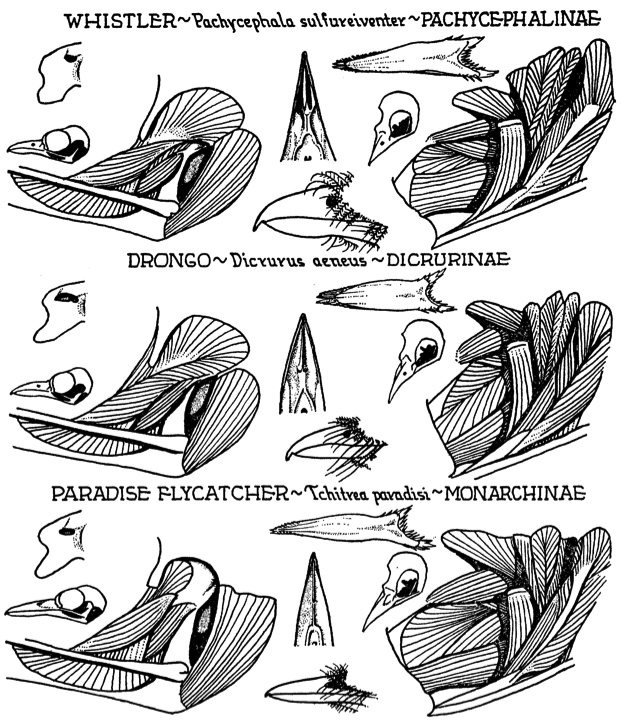

The monarchs had long been grouped with all other Old World flycatchers in the large, diverse family Muscicapidae. This classification scheme persisted throughout the early and mid-20th century[11] [12] , and only in the 1950s did a more modern picture begin to arise, with scientists noting the unique syrinx morphology (the 'turdine thumb') and spotting of juvenile plumage. Delacour (1947) also notes the behavioural difference between monarchs and the muscicapines, with the former 'behaving less like flycatchers and more like arboreal insect-gleaners'[13] .

The contemporary understanding of monarch systematics has its roots in the morphological analyses undertaken by W. J. Beecher (1953), in which the monarchs were split out from the other Old World flycatchers into the newly minted Monarchidae, including whistlers, drongos, and vireos, each of which are now placed in their separate families. He characterised the new family based on morphological differences in their skulls, associated muscles, tongues, and bills[14] .

|

| Characters between the subfamilies of Beecher's Monarchidae (1953), figure adapted from Beecher (1953). |

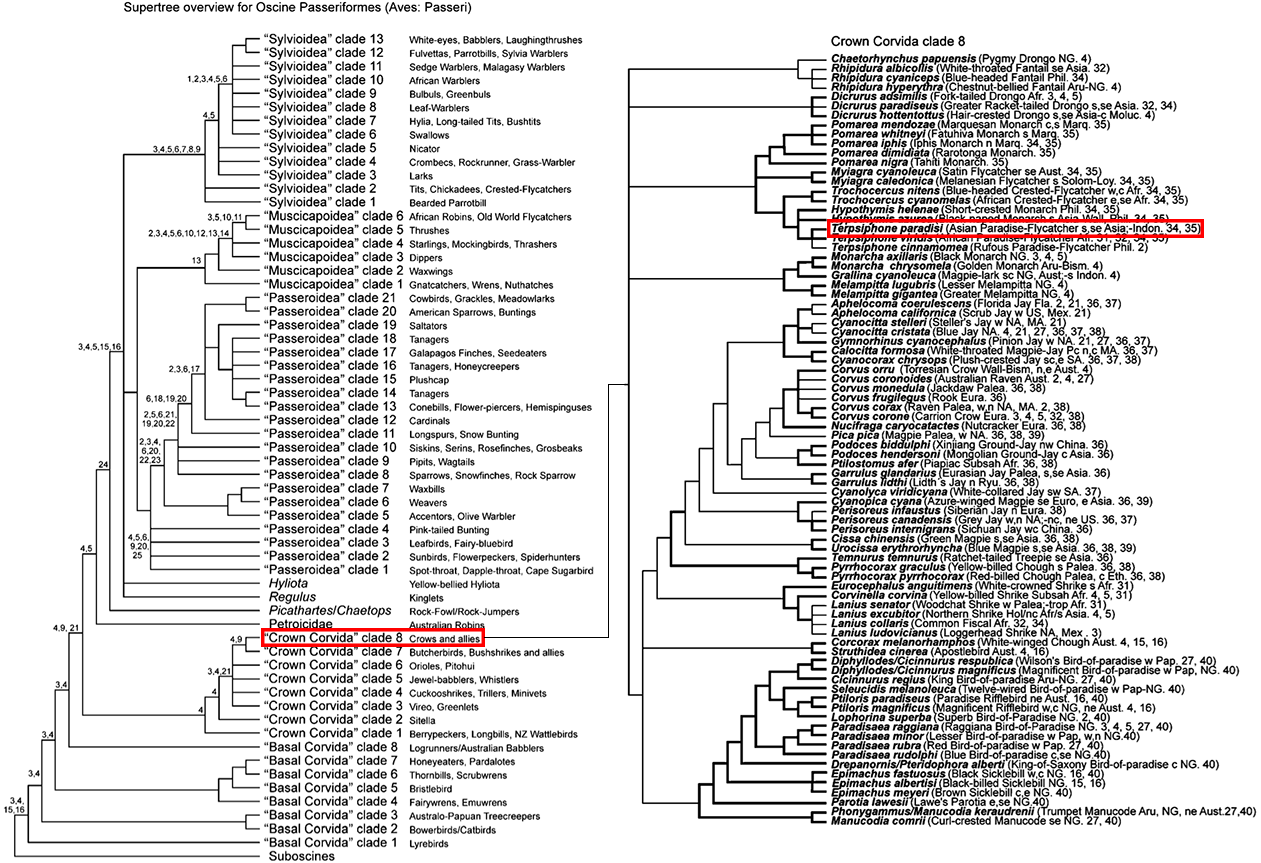

Sibley & Ahlquist's seminal 1990 paper employing DNA-DNA hybridisation techniques placed the monarch-flycatchers with its contemporary allies, suggesting a crow-like common ancestorunaffiliated with the true muscicapines. The drongos were ranked as a subfamily of the crows (Corvidae), and the monarchs one of three tribes within the drongo subfamily[15] . The validity of the three groupings was supported by Christidis & Schodde's 1991 protein-based phylogeny[16] , and importantly were in agreement with earlier morphological and behavioural analyses. This three-group scheme has remained largely unchanged[17] - contemporary treatments often closely mirror this understanding. Numerous papers employing nucleotide data have lent further credence to the result, with Jønsson & Fjeldså's 2006 oscine phylogenetic supertree (presented below) incorporating such findings[18] .

|

| Placement of the Asian Paradise-flycatcher within the oscine phylogenetic supertree with only tree topology shown and not branch lengths; numbers in the left section indicate references that support a node by >95 Bayesian posterior probability or by a bootstrap value >75 (Figure adapted from Jønsson & Fjeldså, 2005). |

Subspecies

There are currently fourteen recognised subspecies, with the two native subspecies marked in bold[19] :| Subspecies |

Distribution |

| T. p. leucogaster (Swainson, 1838) |

breeds W Tien Shan S to N Afghanistan, N Pakistan, NW & NC India and W & C Nepal; non-breeding E Pakistan and peninsular India |

| T. p. paradisi (Linnaeus, 1758) |

C & S India, C Bangladesh and SW Myanmar; non-breeding also Sri Lanka |

| T. p. ceylonensis (Zarudny & Härms, 1912) |

Sri Lanka |

| T. p. affinis (Blyth, 1846) |

Peninsular Malaysia and Sumatra |

| T. p. saturatior (Salomonsen, 1933) |

breeds E Nepal E to NE India, E Bangladesh and N Myanmar; non-breeding also Malay Peninsula |

| T. p. nicobarica Oates, 1890 |

C Nicobar Is |

| T. p. burmae (Salomonsen, 1933) |

C Myanmar |

| T. p. indochinensis (Salomonsen, 1933) |

E Myanmar, S China (S Yunnan) and Thailand E to Indochina |

| T. p. procera (Richmond, 1903) |

Simeulue I (off NW Sumatra) |

| T. p. insularis Salvadori, 1887 |

Nias I (off NW Sumatra) |

| T. p. borneensis (E. J. O. Hartert, 1916) |

Borneo |

| T. p. floris Büttikofer, 1894 |

Sumbawa, Flores, Lembata, Alor (Lesser Sundas) |

| T. p. sumbaensis A. B. Meyer, 1894 |

Sumba I (Lesser Sundas) |

| T. p. incei (Gould, 1852) |

breeds C, E & NE China, Russian Far East (S Ussuriland) and N Korea; non-breeding mainly SE Asia |

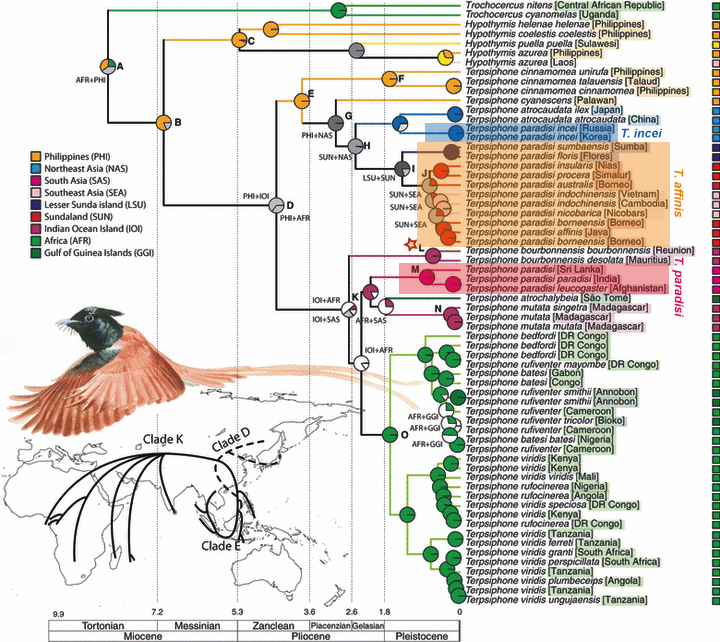

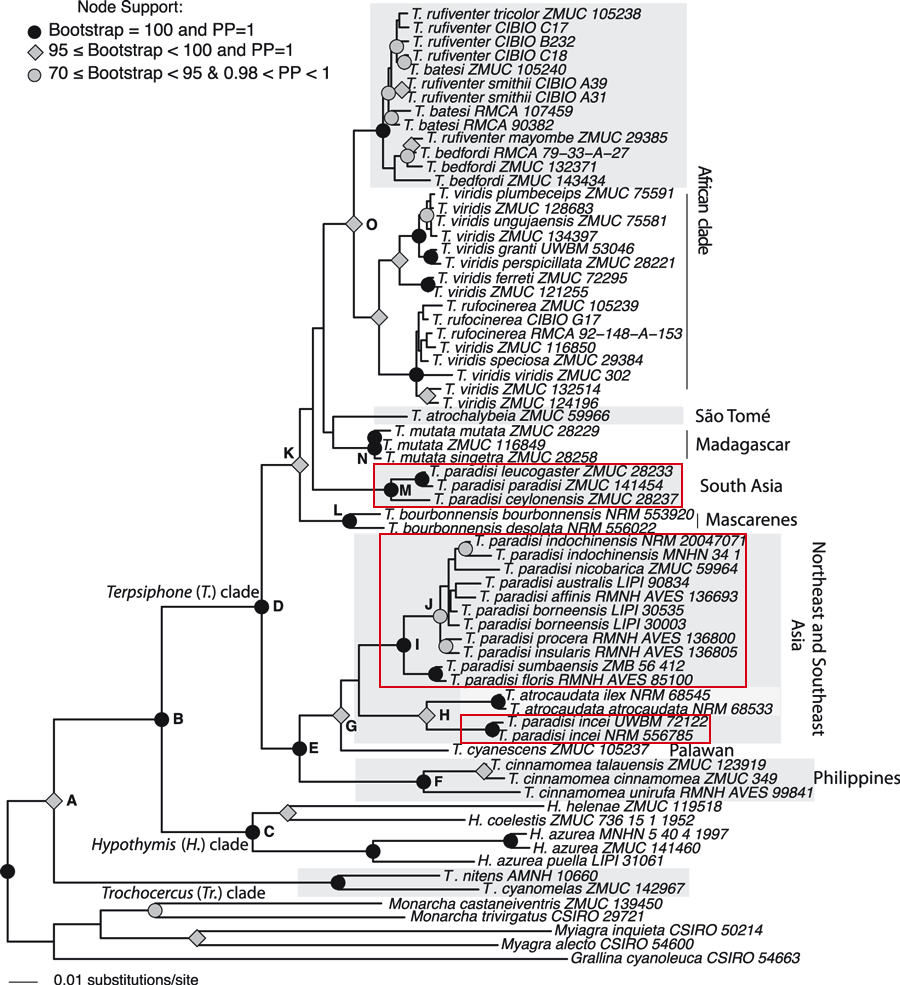

In spite of the work done on the placement of the monarchs within the passerines, the internal phylogeny within the monarchs remained poorly resolved, with scarce molecular data available until recent years. Fabre et al. (2012) was the first comprehensive phylogenetic reconstruction of Monarchidae, suggesting an eastern Asian origin for Terpsiphone, with multiple simultaneous colonisations of southwest Asia, the Indian Ocean, and Africa.

|

| Ancestral area reconstructions of Old World Monarchidae. The tree is a chronogram (strict molecular clock) based on a beast Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) analysis of the combined dataset. Maximum likelihood ancestral area reconstructions were conducted on 1000 randomly sampled trees (allowing for alternative topologies to be included) from the posterior distribution of the beast analysis. The result from the Model 1 (M1) is presented here. The distribution for each taxon is presented to the right of the taxon name. Coloured pies indicate the origin of a given node. White- and grey-shaded pies indicate mixed origin, as indicated next to the pie in abbreviated form. The map indicates the inferred dispersal and colonization routes of members of the Terpsiphone. The star indicates the island calibration points used for the absolute dating. Water colour by Jon Fjeldså. Figure adapted from Fabre et al. (2012). |

The most interesting finding was the apparent polyphyly of the species. They proposed that the Asian Paradise-flycatcher was composed of populations that had retained the ancestral plumage of the genus, and should instead be three species: the Indian Paradise-flycatcher T. paradisi (3 subspecies), the Oriental (or Blyth's) Paradise-flycatcher T. affinis (9 subspecies), and the Amur Paradise-flycatcher T. incei (monotypic)[20] .

|

| Maximum likelihood topology of Old World Monarchidae produced from the combined analysis. Circles and diamonds at nodes represent maximum likelihood (ML) bootstrap support values and Bayesian posterior probabilities (PP). Black circle: ML bootstrap = 100 and posterior probability = 1; grey diamond: bootstrap ‡ 95 and PP = 1; grey circle: bootstrap ‡ 70 and PP ‡ 0.98. Figure adapted from Fabre et al. (2012). |

The subspecies would be reallocated as follows:

| Terpsiphone paradisi |

Terpsiphone affinis |

Terpsiphone incei |

| T. p. leucogaster (Swainson, 1838) |

T. a. affinis (Blyth, 1846) |

T. incei (Gould, 1852) |

| T. p. paradisi (Linnaeus, 1758) |

T. a. saturatior (Salomonsen, 1933) |

|

| T. p. ceylonensis (Zarudny & Härms, 1912) |

T. a. nicobarica Oates, 1890 |

|

| T. a. burmae (Salomonsen, 1933) |

||

| T. a. indochinensis (Salomonsen, 1933) |

||

| T. a. procera (Richmond, 1903) |

||

| T. a. insularis Salvadori, 1887 |

||

| T. a. borneensis (E. J. O. Hartert, 1916) |

||

| T. a. floris Büttikofer, 1894 |

||

| T. a. sumbaensis A. B. Meyer, 1894 |

- ^ Jobling, J. A. (2010). The Helm dictionary of scientific bird names: From aalge to zusii (p. 382). Christopher Helm, London.

- ^ del Hoyo, C., Elliott, A., & Christie, D. (2006). Handbook of the birds of the world (Vol. 11). Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

- ^ del Hoyo, C., Elliott, A., & Christie, D. (2006). Handbook of the birds of the world (Vol. 11). Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

- ^ Mizuta, T. & Yamagishi S. (1998). 'Breeding biology of monogamous Asian Paradise Flycatcher Terpsiphone paradisi (Aves: Monarchinae): a special reference to colour dimorphism and exaggerated long tails in male'. Raffles Bulletin of Zoology, 46(1), 101–112.

- ^ Rasmussen, P. C. & Anderton, J. C. (2005). Birds of South Asia: The Ripley Guide (Vol. 2) (pp. 332–333). Smithsonian Institution and Lynx Edicions.

- ^ Eaton, J. S., van Balen, B., Brickle, N., Rheindt, F. E. (2016). Birds of the Indonesian Archipelago. 496 pp. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

- ^ BirdLife International (2012). Terpsiphone paradisi. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2012: e.T22707146A39429840. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2012-1.RLTS.T22707146A39429840.en. Retrieved on 05 September 2016.

- ^ Linné, Carl von (1758). Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classses, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (p. 107). Göttingen.

- ^

Naturalis Biodiversity Center: Naturalis Biodiversity Center (NL) - Aves, 2016-02-23. Retrieved from http://www.gbif.org/occurrence/1227388767 on 20 October 2016.

Jarvis, E.D., et al. (2014). Whole-genome analyses resolve early branches in the tree of life of modern birds. Science, 346(6215), 1320-1331. doi:10.1126/science.1253451. PMC 4405904. PMID 25504713.

Stresemann, E. (1930). Eine zweite Vögelsammlung aus Kwangsi. Journal für Ornithologie, 78(1), 76-86. doi:10.1007/bf01950902

Beecher, W. J. (1953). A phylogeny of the oscines. The Auk, 70(3), 270-333. doi:10.2307/4081321

Sibley, C. G. & Ahlquist, J. E. (1990). Phylogeny and classification of birds. Yale University Press, New Haven, Conn.

Schodde, R., & Mason, I. J. (1999). The directory of Australian birds: A taxonomic and zoogeographic atlas of the biodiversity of birds in Australia and its territories. CSIRO Pub.,

Collingwood, VIC.

Moeliker, K. (2016). Asian Paradise-flycatcher (Terpsiphone paradisi). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. Retrieved from http://www.hbw.com/node/59195 on 05 September 2016.

Fabre, P., Irestedt, M., Fjeldså, J., Bristol, R., Groombridge, J. J., Irham, M., & Jønsson, K. A. (2012). Dynamic colonization exchanges between continents and islands drive diversification in paradise-flycatchers (Terpsiphone, Monarchidae). Journal of Biogeography, 39(10), 1900-1918. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2012.02744.x

'Terpsiphone [paradisi, affinis, or incei] - AviBase'. (n.d.). Avibase. Retrieved from http://avibase.bsc-eoc.org/species.jsp?lang=EN&avibaseid=12E18743 on 05 September 2016.