Table of Contents

Common Birdwing

Meet Singapore’s largest and only CITES-listed butterfly. Named after Zeus' daughter, Helen of Troy, this beauty is a sight to behold. In fact, the common birdwing was among the nominees to be our national butterfly.[1]

Want to know more and see one for yourself? Read on!

|

| Troides helena. Source: Pasha Kirillov on Flickr, Licensed under Creative Commons under terms of CC-BY-SA-2.0 |

1. Habitat and distribution

If the common birdwing is CITES-listed... it must be super rare, right?

Not exactly. In fact, NParks considers this butterfly as "moderately common", so there is a good chance that you will be able to encounter one.

==1.1 Singapore[2]

The common birdwing is a forest/jungle species, but you can also find it in our local parks and gardens, where it enhances the aesthetic pleasure of visitors.

Like many butterflies, the common birdwing is a specialist that is dependent on its host plant. For Troides species, these are Aristolochia vines. Finding the host plant will greatly increase your chances of spotting insects. You might also want to look above, since the butterflies are also known to flutter around treetops.

|

| Host plant, Aristolochia acuminata grown in a garden at Khoo Teck Puat Hospital . Source: Author's own |

1.2 Global

Of all birdwing species, the common birdwing has the widest geographical range and occurs mainly in Asia including in countries such as India, Nepal, Bangladesh, Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia, Laos, Myanmar and Southern China.[3] Hong Kong is the upper latitudinal limit of the range.[4]Troides helena can be found in forests with an elevation between 0m to 1000m.[5] Though forests are their most preferred habitats, they can occasionally be spotted in gardens and villages.

|

| Distribution of the common birdwing butterfly as per recorded sightings in the Global Biodiversity Information Facility. Source: GBIF under CC license |

2. Morphology and life history

How do I know what I'm looking at is a common birdwing?It is difficult to misidentify the common birdwing in Singapore due to its remarkable appearance - it is the only birdwing in Singapore, save for the highly elusive Malayan birdwing which has not been recorded in Singapore in recent years.

==2.1 Adult stage[6]

The common birdwing adult (also known as the imago) sometimes possesses a reddened pronotum (at the front of the thorax, when looked from the above).

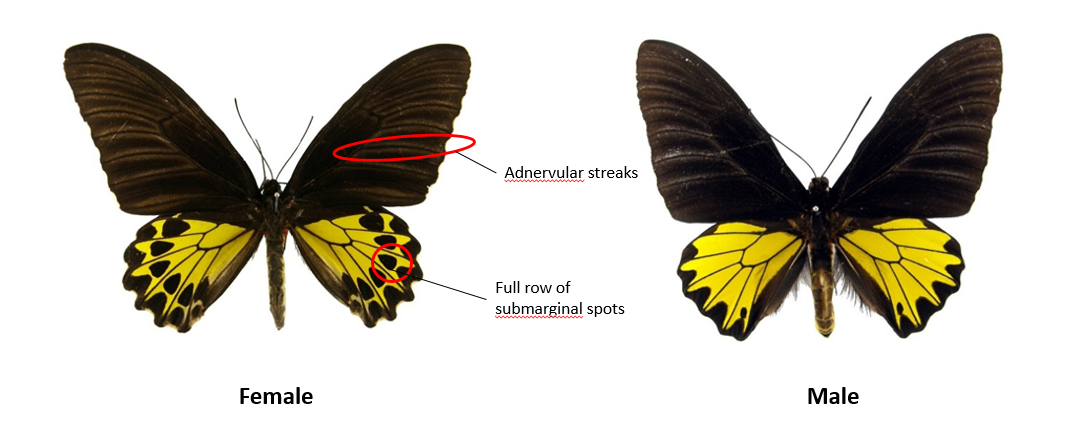

Boasting a wingspan of between 14cm to 19cm with the females generally larger, the common birdwing is a marvel to look at. The rich, black forewings are especially enlarged and resemble a stylised version of a bird’s wing, hence its name. The veins of the forewing are lined with greyish streaks. The hindwings, in contrast, are a striking yellow with black veins and are sexually dimorphic - females have a full row of submarginal spots, which are either reduced or absent in their male counterparts. They also have more obvious adnervular streaks.

|

| Comparison between the male and female Troides helena. Source: Photo © by Naturhistorisches Museum Wien; Photographer Thomas Neubauer, licensed under Creative Commons under terms of CC-BY-SA-3.0. Edited by S.T. Ng. |

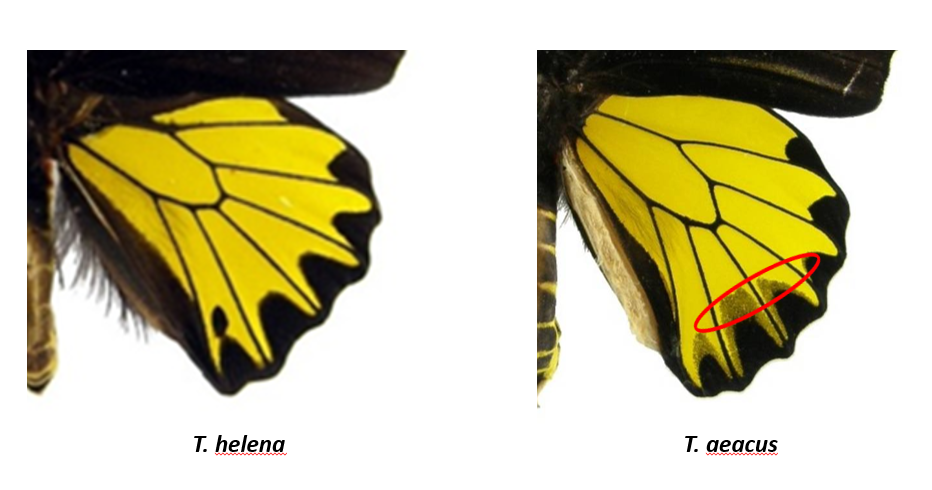

To distinguish the common birdwing from the similar looking golden birdwing (Troides aeacus) in particular, look out for the marginal spots in spaces 2 and 3 on the hindwing – they should not be black dusted.[7] See if you can spot the difference below.

|

| Upperside hindwings of T. helena and T. aeacus. Source: Photo © by Naturhistorisches Museum Wien; Photographer Thomas Neubauer, licensed under Creative Commons under terms of CC-BY-SA-3.0. Edited by S. T. Ng. (permission for T. aeacus image pending) |

2.2 Common characteristics of family Papilionidae (swallowtails)

The Troides genus including the common birdwing is a member of the swallowtail family, a group of colourful butterflies which include some of the largest in the world. Other butterflies in Singapore included in this group are the common rose (Pachliopta aristolochiae) and lime butterfly (Papilio demolus). They share some common characteristics. The head is black with small palpi appressed. The black legs have a simple pair of tarsal claws, and the fore tibia’s inner edge bear large, leaf-like medial spines. The abdomen is light brown with a yellow underside.[8]2.3 Growing stages

Just like other butterflies, the common birdwing was not born beautiful. It has to go through the phases of being a caterpillar and pupa first. The following is based on a description by Tan (2011):[9]Single, fairly large (1.9 – 2.0mm) eggs are usually laid on the stems or the leaves of the host plant (Aristolochia spp.). The eggs can be either orange-yellow in colour or have a whitish granulated surface. The larvae hatches after approximately six days by eating the egg shell.

Newly hatched larvae are approximately 4.5mm long. It is mostly reddish brown with a black head and orange colouration on the anterior, posterior and 4th abdominal segments. Along its body are rows of tubercules with setae (spines) at the terminal ends. During the first moult to the 2nd instar, the larva loses its setae and the tubercules are longer and fleshier. By the 3rd instar, the larvae develops the distinctive pink saddle which becomes more whitish-brown and prominent with subsequent moults. The 4th instar sees the development of white lateral patches on the thorax. The 5th and final larval instar can reach up to 60mm and lasts approximately 5 days before pupation. All the instars also have an orange osmeterium (defensive organ), which is typically hidden but can be everted when the larva senses a threat.[10]

Before moulting to the pupa, the larva rests on the lower surface of the steam and uses a silk pad and silk girdle stabilise itself. A leaf-like pupa forms. Initially, the pupa is either green or brown in colour. Over the course of development the pupa turns black and an adult butterfly emerges after 19-20 days.

|

| Life History of Troides helena. Source: Photo © by Soon Chye at sgbug.org. |

3. Ecology and behaviour

What are the explanations behind my observations of the common birdwing?3.1 Warning colouration

Troides larvae are known to feed exclusively on the leaves of Aristolochia spp., which produces a secondary metabolite known as aristolochic acid. Varying concentrations of this acid can be found in members of the Troidini tribe and is retained from larval stages to adulthood.[11] The larvae of Troides butterflies use aristolochic acid to deter predators such as sparrows.[12] The toxicity of these butterflies may be reflected in their aposematic colouration. This is rather similar to the common example of the monarch butterfly and milkweed plant.3.2 Courtship

Protandry, where males emerge before females, is common in insects. Male birdwing butterflies are known to circle the host plants in search of newly emerged females.[13] Mating with vigin females will increase the chances of reproductive success with respect to the number of eggs fertilised, in comparison with females which have already mated.[14]3.3 Flight pattern

The forewings beat relatively quickly whereas the hindwings remain stationary. The butterfly flies at a moderate speed in comparison to other butterflies.[15]3.4 Daily activity

The following observations were made by Krafiani (2010) in Insect Museum and Butterflies Park of Taman Mini Indonesia Indah. [16] Do note that the time is in WIB, but you may use it as a rough guide if you want to observe the common birdwing in the field.0800 – 0900 : Nectar feeding

0900 – 1000 : Flying

1000 – 1100 : Peak of activity and interaction

1300 – 1700 : Beginning to roost

Males are noted to be more active than females as they actively seek a mate.

4. Conservation

Why is this butterfly listed in CITES in the first place? Does that mean that it faces extinction?As mentioned, this butterfly is not particularly elusive and is thankfully not on the brink of extinction at the moment. However, the threats it faces from illegal trade and habitat destruction are very real.

4.1 Illegal butterfly trade

As this attractive butterfly is highly sought after by collectors, it is currently listed in Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna along with other species of the genus Troides.[17] This means that while trade of T. helenais not entirely banned, trade is restricted and controlled by the parties of the convention. As a party to the convention, Singapore enforces CITES regulations in local law through the Endangered Species (Import and Export) act. Nevertheless, the illegal butterfly trade is still pervasive, and is estimated to be worth a whopping $200 million a year.[18] Perfect specimens are prized and can fetch up to tens of thousands of dollars.Troides helena has yet to be assessed for the IUCN Red List.

The common birdwing has been artificially bred in farms. This is to help meet the demand of butterfly without decimating the wild populations while providing locals with an incentive to preserve the natural environment.[19]

4.2 Flagship species

In a survey by Barua and Gurdak, Troides helena emerged as the most popular butterfly among respondents and showed potential for use as a flagship species for invertebrate conservation, which is underfunded compared to other taxa due to the lack of public support.[20] This can be attributed to the very same striking appearance that made it so appealing to collectors.[21]4.3 Land use change

Troides helena has yet to be assessed for the IUCN Red List. Like many other plants and animals, the common birdwing is threatened by habitat loss due to clearance of land for agriculture and urbanisation.[22]In Singapore, the butterfly may be affected by habitat fragmentation, whereby forests are split into patches by roads and other factors of the man-made environment. As mentioned, the common birdwing's host plant are Aristolochia vines. The natural host plants have been extirpated, with introduced species like the indian birthwort (Aristolochia tagala) taking their places.[23] Other members of the same genus are sometimes deliberately planted in curated parks and gardens.

Ensuring connectivity in our green spaces may help in the local conservation of the species as it helps to increase the dispersal distance of butterflies.[24]

5. Taxonomy

5.1 Description

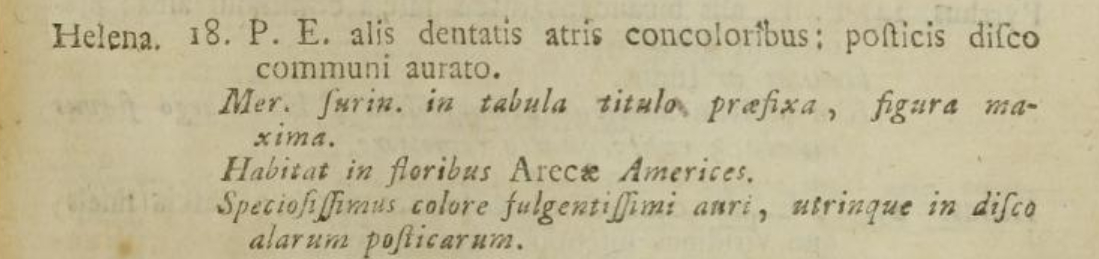

Troides helena was originally classified as Papillio (eques) helena by Carl Linneaus in Systema Naturale.[25] It was later classified under the genus Troides (Hübner, 1819) by Rothschild (1895) when he put all the "birdwing" butterflies under the same genus.[26] There was some debate on the splitting of the genera of birdwings and the butterflies have been put together and split multiple times.[27] Munroe (1961) keyed out the differences between Ornithoptera and Troides based on morphology.[28] Phylogenetic data supports the monophyly of these genera, as elaborated on in the next section. |

| Original species description by Carl Linneaus (1758) in Systema Naturale. Source: Biodiversity Heritage Library under Fair Use. |

5.2 Type information

The original description by Linnaeus (1758) was based on an illustration in Merian's "Surinamensium" in about 1717, which therefore is the type of "Papilio Eques Trojanus helena". The illustration depicted the imago in black and white.[29]5.3 Synonyms

Troides helena has 12 synonyms.[30]- Ornithoptera helena

- Ornithoptera helenaeuthycrates

- Ornithoptera helenamosychlus

- Ornithoptera helenasagittatus

- Papilio helena

- Papilio pompeus

- Troides ferrari

- Troides helenadempoensis

- Troides helenamannus

- Troides helenapropinquus

- Troides helenarayae

- Troides pompea

5.4 Classification

Class Animalia (animals)Phylum Arthropoda (arthropods)

Class insecta (insects)

Order lepidoptera (moths and butterflies)

Superfamily Papilionoidea

Family Papilionidae (swallowtails)

Genus Troides

Species helena

5.5 Subspecies

Troides helena has 17 subspecies. The species documented in Singapore is Troides helena cerberus. [31]- T. h. antileuca Rothschild, 1908

- T. h. bunguranensis Ohya, 1982

- T. h. cerberus (C. & R. Felder, 1865)

- T. h. demeter Rumbucher & Schäffler, 2005

- T. h. dempoensis Deslisle, 1993

- T. h. euthycrates Fruhstorfer, 1913

- T. h. ferrari Tytler, 1926

- T. h. hahneli Rumbucher & Schäffler, 2005

- T. h. heliconoides (Moore, 1877)

- T. h. hephaestus (Felder, 1865)

- T. h. hermes Hayami, 1991

- T. h. hypnos Rumbucher & Schäffler, 2005

- T. h. isara Rothschild, 1908

- T. h. mopa Rothschild, 1908

- T. h. mosychlus Fruhstorfer, 1913

- T. h. neoris Rothschild, 1908

- T. h. nereides Fruhstorfer, 1906

- T. h. nereis (Doherty, 1891)

- T. h. orientis Parrott, 1991

- T. h. propinquus Rothschild, 1895

- T. h. rayae Deslisle, 1991

- T. h. sagittatus Fruhstorfer, 1896

- T. h. spilotia Rothschild, 1908

- T. h. sugimotoi Hanafusa, 1992

- T. h. typhaon Rothschild, 1908

- T. h. venus Hayami, 1991

6. Phylogeny

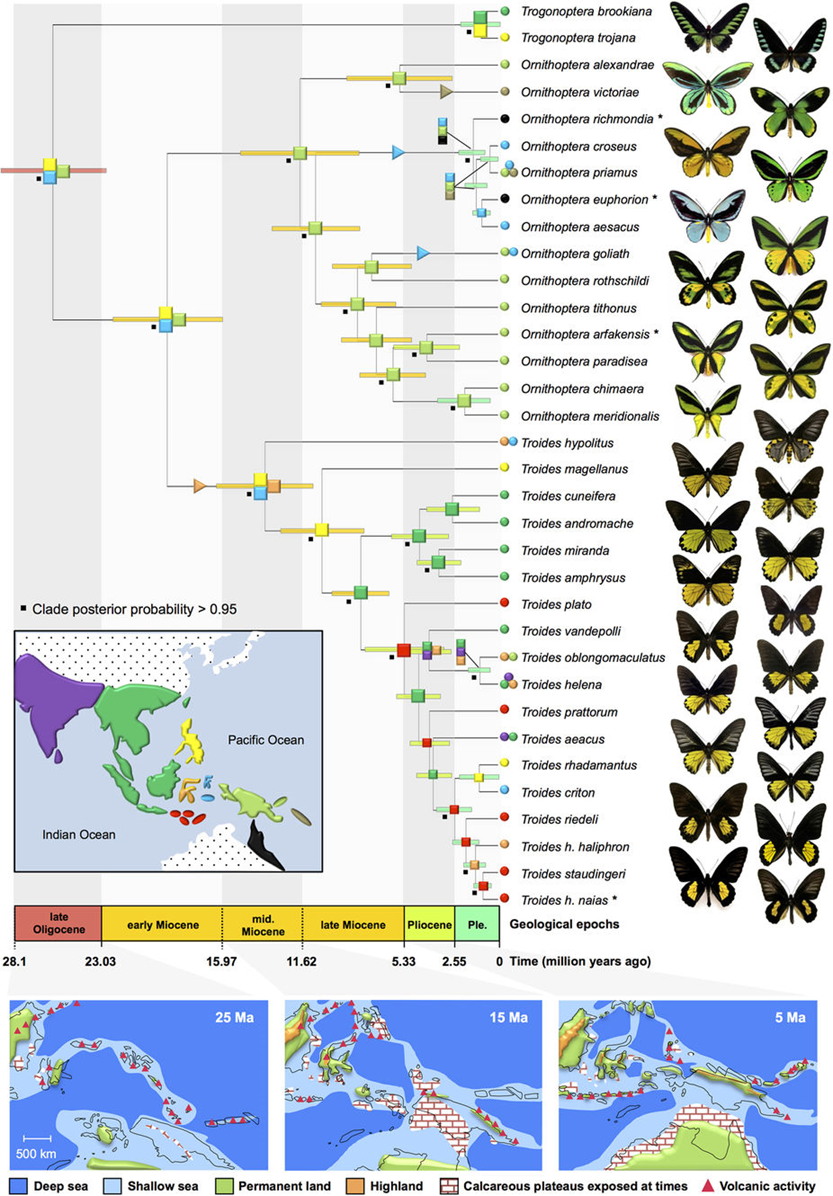

This section is mainly based on a recent study by Condamine et al. (2015).[32] Please note that some of the information cited is in the supplementary material provided by the authors in addition to the main publication.6.1 The birdwing genera

Bayesian analysis was conducted with a nucleotide set comprising five genes (3 mitochondrial genes and 2 nuclear protein-encoding genes) supported the results of preceding studies including that by Kondo and Shinkawa (2003)[33] regarding the monophyly of the birdwings. The nodes at the crown of the genera Ornithoptera, Trogonoptera, and Troides were well supported, with clade posterior probability values higher than 0.95. The outgroups used in the construction of the tree were Cressida and Pharmacophagus, two genera which were the closest to the birdwings.6.2 Relationships between Troides species

However, there is still room for contention when at the species level.Within the Troides genus it was found that all morphological species with the exception of Troides haliphron was monophyletic. Paraphyly was demonstrated in both analyses of mtDNA and nucDNA – the two groups of Troides haliphron were split by Troides staudingeri. Troides haliphron subspecies haliphron and parabu occur in West Sulawesi and the Seleyar Islands, whereas subspecies socrates and naias occur in the lesser Sunda Archipelago.

For Troides helena and Troides oblongomacalutus, detectable differences can only be found in the analysis of mtDNA – there was no variation in nuclear DNA (which has a slower mutation rate in comparison). This may, as the authors suggested, be due to the recent speciation event or that speciation was not complete in the first place.

6.3 Biogeographical history

Ancestral areas were estimated using the model BioGeoBEARS. Findings showed that Troides migrated across the Wallace line on multiple occasions.The authors also used the likelihood approach, GeoSSE in the R package diversitree to estimate speciation and extinction rates as well as range evolution based on region. They also tested the hypothesis that Wallacea was acting as a species pump. Results showed that while the area served as a biogeographical pathway for butterflies, diversification rates were not affected.

|

| Dated Bayesian phylogenetic tree of the birdwing butterflies in the Indomalayan-Australian archipelago. Source: Condamine et al. (2015) under fair use. |

=

=

7. References=

=

This page is for educational purposes. To a reasonable extent, an effort has been made to contact the owners of the images and media featured on this page. If you are the owner of any online content featured here, please contact e0008145@u.nus.edu if you wish for your content to be removed, or have any other comments and concerns. Thank you!

- ^ Nature Society Singapore (2015). Singapore's national butterfly. Retrieved from http://www.nationalbutterfly.org.sg/#page6

- ^

==

==

==

National Parks Board (2013). Troides helena cerberus (C & R Felder, 1865). https://florafaunaweb.nparks.gov.sg/special-pages/animal-detail.aspx?id=325

Collins, N. M. & Morris, M. G. (1985). Threatened Swallowtail Butterflies of the World: The IUCN Red Data Book. Gland & Cambridge: IUCN. ISBN 978-2-88032-603-6.

Van Lien, V., & Yuan, D. (2003). The differences of butterfly (Lepidoptera, Papilionoidea) communities in habitats with various degrees of disturbance and altitudes in tropical forests of Vietnam. Biodiversity & Conservation, 12(6), 1099-1111.

==

==

==

Blyth, W. M. A. (1957). Butterflies of the Indian Region. Bombay Natural History Society, Bombay. Pp. 372.

Corbet, A. S, Pendlebury, H. M., & Eliot, J. N. (1978). The Butterflies of the Malay Peninsula (4th ed). Kuala Lumpur, Selangor: Malayan Nature Society.

Corbet, A. S., Pendlebury, H. M., & Eliot, J. N. (1978). The Butterflies of the Malay Peninsula (4th ed). Kuala Lumpur, Selangor: Malayan Nature Society.

Tan, H. (2011). Life History of the Common Birdwing. Retrieved from http://butterflycircle.blogspot.sg/2011/08/life-history-of-common-birdwing.html

Blyth, W. MA (1957): Butterflies of the Indian Region. Bombay Natural History Society, Bombay. Pp. 370.

Tsukada, E. & Nishiyama, Y. (1982). Butterflies of the South East Asian Islands. Vol.1. Papilionidae. Plapac Co.Ltd., Tokyo, 457 pp.

Straatman, R., 1976. Hybridisation of birdwing butterflies (Lepidoptera: Papilionidae) in Papua New Guinea. Lepidoptera Science, 27(4), pp.156-162.

Khew, S. K. (2010). A field guide to the butterflies of Singapore.

Krafiani, S. S. (2010). Butterfly’s Daily Activities of Troideshelena (Linn.) in Insects Museum and Butterflies Park of Taman Mini Indonesia Indah. (Bachelor thesis). Retrieved from http://mobile.repository.ipb.ac.id/handle/123456789/59746

CITES (2017). Appendices I, II and III. Retrieved from https://cites.org/eng/app/appendices.php

Van der Heyden, T. (2011). Local and effective: Two projects of butterfly farming in Cambodia and Tanzania (Insecta: Lepidoptera). SHILAP Revista de Lepidopterología, 39(155), 267-270.

Cardoso, P., Erwin, T. L., Borges, P. A., & New, T. R. (2011). The seven impediments in invertebrate conservation and how to overcome them. Biological Conservation, 144(11), 2647-2655.

Young, J.J. and Reels, G.T. (1998) A brief note on the distribution and conservation of Birdwing butterflies in Hong Kong. Porcupine!, 17: 10

Jain, A., (2016). Ecology and conservation of butterflies in a transformed tropical landscape.(Doctoral dissertation).

Jain, A., Chong, K.Y., Chua, M.A.H. and Clements, G.R., 2014. Moving away from paper corridors in Southeast Asia. Conservation Biology, 28(4), pp.889-891.

Linnaeus, C. (1758). Systema naturale. Retrieved from https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/10277#page/483/mode/1up

Haugum, J., & Low, A. M. (1985). A monograph of the birdwing butterflies, the systematics of Ornithoptera, Troides and related genera: vol. 2, the genera Trogonoptera, Ripponia and Troides. Leiden, Copenhagen: Scandinavian Science Press Ltd. p242.

Insectoid info (n.d.) Troides helena. Retrieved from http://insectoid.info/insecta/lepidoptera/papilionidae/troides_helena/

Gan, C. W. & Chan, S. K. M. (2009). A field guide to the butterflies of Singapore. Singapore, Singapore: Nature Society (Singapore).

Condamine, F. L., Toussaint, E. F., Clamens, A. L., Genson, G., Sperling, F. A., & Kergoat, G. J. (2015). Deciphering the evolution of birdwing butterflies 150 years after Alfred Russel Wallace. Scientific reports, 5, 11860.

Kondo, K. & Shinkawa, T. (2003). Molecular systematics of birdwing butterflies (Papilionidae) inferred from mitochondrial ND5 gene. Journal of the Lepidopterists Society, 57(1), 17-24.