Wagler's Pit Viper, Temple Pit Viper

|

| The typical colouration of an adult female T. wagleri. Note the small keeled head scales. Photo credit: Zestin Soh |

Table of Contents

Biological Information

Venom

| "Tubing" an individual for body measurements. Photo credit: Prarthini Selveindran |

The venom of T. wagleri is haemotoxic. While the bite is not regarded as fatal, it may cause severe pain and local swelling. A unique family of peptides called "Waglerins" (Schmidt et al., 1992) was isolated from T. wagleri venom. Unlike other peptides which have proteolytic and haemolytic activity, these family of Waglerin peptides apparent lack of neurotoxicity imply that the venom has a unique mechanism of action. One of the compounds in its venom, Waglerin-1, has been found to have the novel function of blocking nicotinic acetylcholine receptors at the neuromuscular junction, blocking uptake of Na+ and thus inhibiting muscular movements (McArdle et al., 1999).

The muscular-inhibiting action of Waglerin peptides has found a applied use in cosmetic products. Syn®-ake is a patented tripeptide marketed as "Botox in a Bottle" which has anti-wrinkle properties that mimics Waglerin-1. According to its manufacturers, Pentapham Ltd, Basel, Switzerland, the cosmetic product is "clinically proven to reduce wrinkles by up to 52 per cent in just 28 days" and is promoted as a "painless cosmetic alternative to controversially discussed muscle-relaxing anti-aging treatments like botulinum toxin". Strangely enough, most of the websites selling the product have images of snakes that are not pit vipers, let alone T. wagleri.

Conservation & Association with Humans

IUCN Conservation Status

This species is currently listed under Least Concern (LC) because it is widely distributed, is present in many protected areas, and the only current threat (illegal collection for the pet trade) does not seem to be heavily impacting its population.What do I do if I see a Tropidolaemus wagleri in the wild?

Leave it alone. They will probably not even appear perturbed by your presence if you have not had close contact. As T. wagleri are known to be relatively docile in nature, they will usually just stay still. If the snake moves away (it is quite unlikely it will move towards you), do not hinder it. Rather, get out of its way, admire the snake from a good distance (~2 meters), and perhaps take a photograph or two and continue on your journey.The Fear of Snakes

Ophidiophobia refers to the abnormal fear of snakes. The word is derived from ophis (Gk) = "snakes". Snakes are often perceived as being particularly vicious and terrifying creatures. Religious and cultural symbols and references allude to two extremes: being god-like as well as representing craftiness. Snakes are held in high regard in Hindu, Australian Aboriginal, Cambodian mythology as well as ancient Egyptian mythology. In Judeo-Christian tradition, the serpent, which was said to be the most crafty, tempted Eve in the Garden of Eden.Popular culture and Hollywood media also play a role in perpetrating the frightening and nightmarish monsters with films such as Anaconda and Snakes on a Plane. Indiana Jones, the intrepid explorer, is a character famous for being a victim of ophidiophobia. Most conveniently, he somehow encounters extremely large-sized snakes wherever he goes.

Colonial Perspectives

Colonial explorers in the Southeast Asian region often encountered pit vipers (Tropidolaemus or Trimeresurus species) in their jungle explorations. With descriptions of the snake like "he grew mad with rage", it is no wonder why colonial masters of the past described the Tropics as exotic regions full of danger and excitement:"On the stem of a tree a grass-green Lachesis snake was lying in an attitude of attack, his body wound round the trunk, his head stretched straight out. In the very nick of time I managed to get hold my Malay and drag him out of danger at the identical second when the snake struck out to bite. With a blow on the creature's head I felled him to the ground, where we held him down with canes not injure his skin. He opened his fearful mouth, armed with two mighty poisonous fangs, and when struck a stick between his jaws he grew mad with rage, and bit it so furiously that it was smashed and the bits flew out in all directions." -Eric Mjöberg "Forest Life and Adventures in the Malay Archipelago", 1930.

Tourist Attraction

A Buddhist temple in Penang, Chor Soo Kong Temple, is famous among tourists for keeping T. wagleri near its altars. According to urban legend, the snakes sought shelter at the temple after its construction in the mid-1800s. Instead of getting rid of them, the monks provided a refuge for them, thus providing the apparent basis for the peaceful coexistence between humans and reptilian wildlife.Many individuals, often separated according to sex, are put on wooden stands and appear relatively sluggish. Although this is not atypical behaviour of T. wagleri in the wild, their sluggishness could be also be due to the snakes being well-fed, thus eliminating the need to hunt for food. Visitors can even handle and take photographs with the snakes for a small sum of money. The snakes are supposedly milked for their venom on a regular basis though it is unclear whether venom is sold for commercial purposes or just to diminish the snakes' venom supply on a regular basis.

It is clear how large an impact this particular "snake temple" has on the anthropic point of view towards this particular species, extending the temple's snake-keeping practices to the vernacular naming of this species, the "temple pit viper". While a study has yet to be carried out, one cannot help but wonder how severely affected the island population of T. wagleri has been.

Effects on Local Populations

Tropidolaemus wagleri sightings on Penang Island, Malaysia (where the Snake Temple is located) appear to be getting less and less frequent. People used to describe the Chor Soo Kong Temple as swarming with Wagler's pit vipers back in the 1970s and 1980s, while today only a few individuals are out on display. The reasons for this decrease could unsustainable collections of the species for commercial trade, stocking the temple's displays or perhaps habitat loss as the development encroaches on the habitat of T. wagleri.

|

Pet Trade

Wagler's pit vipers are popular pet species and can be found for sale on major reptile pet online stores, with individuals costing up to 220 Euros (as of November 2012). Tropidolaemus wagleri are also commonly sold during reptile fairs in Europe and the USA. They are apparently easily bred in captivity and are reputedly docile and non-fussy nature. Living conditions with high humidity and a relatively stable temperature range of 24 - 30°C is optimal for the captive Wagler's pit vipers.However, as with all venomous species, these snakes should be handled with extreme caution despite their docile reputation. While no reports of T. wagleri envenomation bear fatal consequences so far, the person handling a Wagler's pit viper should not risk the chance of getting bit, for reasons both of the person's safety as well as for the snake's well-being.

Due to the intensive captive breeding of T. wagleri in the pet trade, some pet T. wagleri might no longer be classified as T. wagleri, depending on where the wild-caught parent came from, and might actual be T. subannulatus or T. philippensis.

Also, one should take note that it is illegal to own any species of snake as pets. If you know of someone keeping snakes as pets, do contact the authorities such as AVA (Agri-Food & Veterinary Authority) or ACRES (Animal Concerns Research & Education Society) to prevent any untoward accidents as well as to do your part for conservation of this species!

.

Geographical Distribution

View Tropidolaemus wagleri in a larger map

Southern Thailand (Phang Nga, Pattani, Surat Thani, Nakhon Si Tammarat, Narathiwat, Yala), West Malaysia, Sumatra, Nias, Mentawei Archipelago and Bangka Island (Vogel et al., 2007). There have also been reports of an isolated population of T. wagleri in south Vietnam Minh Hai and Song Be), though these reports have yet to verified (Orlov et al., 2003).

View Tropidolaemus wagleri complex in a larger map

Tropidolaemus wagleri appears to be part of a regional complex, with reports of its range across Southeast Asia. Vogel et al., 2007 have since split the T. wagleri complex into three species. The first cluster being the aforementioned distribution, while the second cluster with the binomen Tropidolaemus subannulatus (Gray, 1842) occurs in Borneo, Sulawesi, Sulu Archipelago and the Philippines. The third cluster, found on Mindanao Island in the Philippines is recognized as Tropidolaemus philippensis (Gray, 1842).

View Singapore - Tropidolaemus wagleri in a larger map

In Singapore, Tropidolaemus wagleri can be found in Bukit Nature Reserve, Central Catchment Reserve and Pulau Tekong.

Nomenclature and Taxonomy

Scientific name

Tropidolaemus wagleri(according to the Integrated Taxonomic Information System, Taxonomic Serial No.: 634939, retrieved 4 November 2012.)

Synonyms

Cophias wagleri Boie 1827 (nomen nudem)[Tropidolaemus] wagleri Wagler 1830

Trimeresurus maculatus Gray 1842

Vernacular names

English: Wagler’s Pit Viper, Temple Pit Viper, Wagler’s Palm ViperMalay / Indonesian: Ular Bangkai Laut, Ular Hijau Ekor Mira

Etymology

Viper: is derived from Latin vivo = "I live" and pario = "I give birth", as this species is ovoviparous and gives birth to live young.The species epithet was named after Johann Georg Wagler(1800-1832), a German zoologist who was the Director of the Zoological Museum at the University of Munich.

Taxonomic Information

Classification

- Animalia

- Chordata

- Vertebrata

- Reptilia Laurenti, 1768

- Squamata Oppel, 1811

- Serpentes Linnaeus, 1758

- Alethinophidia Nopsca, 1923

- Viperidae Opell, 1811

- Crotalinae Oppel, 1811

- TropidolaemusWagler, 1830

- Tropidolaemus wagleri (Boie, 1827)

- TropidolaemusWagler, 1830

- Crotalinae Oppel, 1811

- Viperidae Opell, 1811

- Alethinophidia Nopsca, 1923

- Serpentes Linnaeus, 1758

- Squamata Oppel, 1811

- Reptilia Laurenti, 1768

- Vertebrata

- Chordata

Type Specimen

Neotype MNHN1879.0708, adult female, deposited at the Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle, Paris, France.Type Locality

"Asien"; corrected by neotype designation to Bedagai River (3°30'N, 99°13'E), Sumatera Barat Province, Sumatra, Indonesia.Identification

Members of the Viperidae have the most complex of any venom delivery method. These group of snakes are known as the solenoglyphous snakes. Each maxilla is reduced to a single nub with one fang, a hollow tooth that acts like hypodermic needle to deliver venom. The fangs, which point toward the posterior direction, are folded against the roof of the snakes mouth and can measure as long as half of the head. |

| Visual description of the head shape and presence of fangs between a Viperidae member and a Colubridae member. Pending permission from Merck Manual. |

|

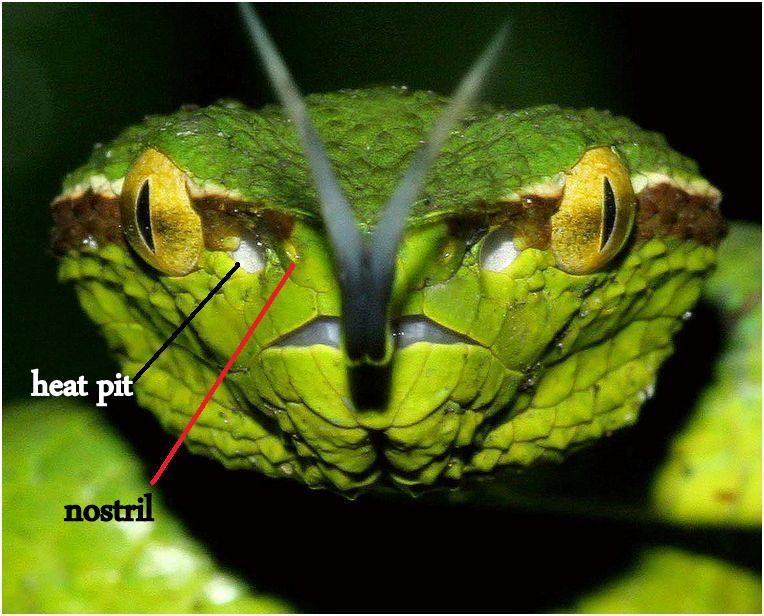

| The heat-sensing pits are located between the eye and the nostril. Photo permission pending: Daniel Rosenberg. |

The heat-sensing pits that so give pit-vipers their name convergently evolved in Viperidae as well as in the more primitive Boidae and Pythonidae. In Viperidae, the pits have evolved only once while the labial pits seen today in Boidae and Pythonidae have evolved multiple times. While the electrophysiology of the pits appear similar, the pits of the two lineages differ in gross structural anatomy.

These pits enable the animals to have what we would imagine to be infrared vision of heat wavelengths between 5 - 30 nanometers. Despite the fact of the long-standing belief that these pits evolved to function in detecting prey, recent studies suggest thermoregulation and predator detection may have also contributed to the evolution of this complex sensory organ.

The heat-sensing pits that so give pit-vipers their name convergently evolved in Viperidae as well as in the more primitive Boidae and Pythonidae. In Viperidae, the pits have evolved only once while the labial pits seen today in Boidae and Pythonidae have evolved multiple times (cite). While the electrophysiology of the pits appear similar, the pits of the two lineages differ in gross structural anatomy.

These pits enable the animals to have what we would imagine to be infrared vision of heat wavelengths between 5 - 30 nanometers. Despite the fact of the long-standing belief that these pits evolved to function in detecting prey, recent studies suggest thermoregulation and predator detection may have also contributed to the evolution of this complex sensory organ.

|

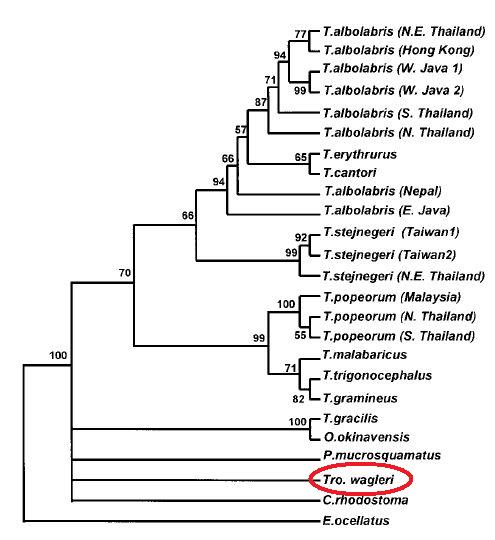

| A maximum-parsimony tree based on cyt b mtDNA sequences showing the relationship of Tropidolaemus wagleri with the rest of the Asian pit vipers (genus Trimeresurus). Bootstrap percentages (> 50%) are indicated below the nodes. Image permission pending: Giannasi et al., 2001. |

Although its common name is a "pit viper", the Tropidolaemus genus differs from all the other main group of Asian pit vipers under the genus Trimeresurus, which include pit vipers collectively known as "bamboo snakes".

| The distinctly keeled small head scales of an adult female T. wagleri. Note the width of each scale is approximately 5mm. Photo credit: Mary-Ruth Low |

The genus Tropidolaemus, which consists of six species, is characterized by absence of nasal pore, upper surfaces of the snout and head covered with distinctly keeled small scales, strongly keeled gular scales, second supralabial not bordering the anterior margin of the loreal pit and topped by a prefoveal and a green colouration in juveniles which may or may not change with growth.

Tropidolaemus wagleri have internasals that are always in contact. Adults exhibit distinct sexual dimorphism. Tropidolaemus wagleri have a distinct triangular head and a golden vertical pupil.

|

| Stark sexual dimorphism: a male rests on top of a female Wagler's pit viper. Photo permission pending: M. A. Muin. |

| Typical adult female colouration. Photo credit: Prarthini Selveindran |

- Adult females

- body black with yellow crossbands

- black postocular stripe

- banded belly

- 23-27 dorsal scale rows at midbody, distinctly keeled

- 134-147 ventral scales

- 45-54 subcaudal scales

- maximum length of up 100 cm

- Adult males

- body vividly green and white spots

- white & red postocular stripe

- uniform belly

- 23 dorsal scale rows at midbody, feebly keeled

- 143-152 ventral scales

- 50-55 subcaudal scales

- maximum length of 75 cm

- Juvenile females

- Body vividly green with white crossbars

Males (adults and juveniles) and juvenile females exhibit a red and white post-ocular stripe. Photo credit: Zestin Soh - White & red postocular stripe

- Uniform belly

- Body vividly green with white crossbars

- Juvenile males

- Body vividly green and white spots

- White & red postocular stripe

- Uniform belly

| Close-up of the golden vertical pupil of T. wagleri. Photo credit: Andrew Ang |

References

Cox, M. J., van Dijk, P. P., Nabhitabhata, J. & Thirakhupt, K., 1998. A photographic guide to snakes and other reptiles of Peninsula Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand. New Holland Publishers (UK) Ltd.

David, P. & Vogel, G. 1996. The snakes of Sumatra. An annotated checklist and key with natural history notes. Edition Chimaira, Frankfurt–am–Main.

Giannasi, N., Malhotra, M. & Thorpe, R. S. 2001. Nuclear and mtDNA phylogenies of the Trimeresurus complex: implications for the gene versus species tree debate. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 19(1):57-66.

McArdle, J. J., Lentz, T. L., Witzemann, V., Schwarz, H., Weinstein, S. A. & Schmidt, J. J. 1999. Waglerin-1 selectively blocks the epsilon form of the muscle nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 289(1):543-550. Available here.

Mjöberg, E. 1930. Forest Life and Adventures in the Malay Archipelago. Oxford University Press, United Kingdom.

Integrated Taxonomic Information System, 2012. Tropidolaemus wagleri. Available here

Lim, F. L. K. and Lee, M T. 1989. Fascinating Snakes of Southeast Asia - An Introduction. Tropical Press, Malaysia.

Orlov, N. L., Ryabov, S. A., Nguyen V. S. & Nguen, Q. T. 2003. New records and data on the poorly known snakes of Vietnam. Russian Journal of Herpetology 10:217-240.

Uetz, P. (editor), Tropidolaemus wagleri, The Reptile Database, accessed Oct 20, 2012. Available here

Schmidt, J. J., Weinstein, S. A. & Smith, L. A. 1992. Molecular properties and structure function relationships of lethal peptides from venom of Wagler's pit viper, Trimeresurus wagleri. Toxicon 30:1027-1036. Available here.

Vogel, G., David, P., Lutz, M., Van Rooijen, J. & Vidal, N. 2007. Revision of the Tropidolaemus wagleri-complex (Serpentes: Viperidae: Crotalinae). I. Definition of included taxa and redescription of Tropidolaemus wagleri (Boie, 1827). Zootaxa 1644:1-40. Abstract available here,

Useful Links

- Reptile Database

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Encyclopedia of Life

- Ecology Asia - Snakes of Southeast Asia

- Digital Nature Archive of Singapore

Recommended Readings

A list of books helpful in identification of local and regional snakes, as well as their general general ecology:

- Baker, N. & Lim, K. K. P. 2008. Wild Animals of Singapore: A photographic guide to mammals, reptiles, amphibians and freshwater fishes. Verterbate Study Group, Nature Society Singapore.

- Greene, H. 2000. Snakes: The Evolution of Mystery in Nature. University of California Press, Berkeley.

- Grismer, L. L. 2011. Amphibians and Reptiles of the Seribuat Archipelago (Peninsular Malaysia). Edition Chimaira, Germany.

- Lim, F. L. K. and Lee, M T. 1989. Fascinating Snakes of Southeast Asia - An Introduction. Tropical Press, Malaysia.

- Lim, K. K. P. & Lim, F. L. K. 1992. A guide to the amphibians and reptiles of Singapore. Singapore Science Centre.

Comments

Please feel free to contact the author of this species page here if you have any clarifications or updated information, over leave a comment below.