Copsychus malabaricus (Scopoli, 1788)

|

| Figure 1. White-Rumped Shama (Photo: Chuck Babbitt) |

Table of Contents

Overview

When thinking about birds in Singapore, one will normally think of the commonly seen Javan Myna or the Eurasian Tree Sparrow, which are both ranked relatively high on the 2010 Mid-Year Bird census (1st and 13th respectively) [1] . One will not normally think, or even know of the White-Rumped Shama (Copsychus malabaricus) (Figure 1), considered to be a rare bird in mainland Singapore [2] . The White-Rumped Shama is a predominantly black bird living in forested areas. Their most renowned feature is their beautiful song, directly resulting in their status as one of the most popular caged birds in Singapore [3] . Do you know that one of the first recordings of bird song ever made was from the White-Rumped Shama? It was recorded by Ludwig Koch from Germany in 1889 [4] .Another interesting fact was them having been featured on both Singapore's stamps and currency notes. They were featured on the S$50 notes of the "Bird Series" currency notes released by the Monetary Authority of Singapore between 1976 and 1984 (Figure 2). In addition, they have been depicted twice in Singapore's postage stamps (50-cent stamp) in both 1962 and 1978 (Figure 2)[5] .

|

| Figure 2. Currency notes and postage stamps of White-Rumped Shama (Photo: Stamps-for-sale.com and SebanaHornbills blog) |

Nomenclature

Binomial (Scientific): Copsychus malabaricus (Scopoli, 1788) [6]Vernacular (Common): English:White-Rumped Shama, Malay: Murai Hutan/Murai Batu [7]

For other languages: see http://eol.org/pages/1177973/names/common_names

Etymology:

"Shama" was derived from a Hindi term meaning "song bird", which was formerly used to describe members of the Thrush family. In Malay, it is called Murai Hutan/Murai Batu or Forest Magpie, as it is usually found in forested areas and has close association with the Magpie Robin in Singapore, despite both species not being true magpies[8] . In addition, the species was called “White-Rumped Shama” due to the obvious and distinctive white rump, in contrast with the black of its body. The rump, a popular term in bird descriptions, refers to the part of the bird's body just before the start of the tail[9] .

Synonyms: None [10]

Original description:

Original description was by J.A. Scopoli from a publication of an account of new descriptions of birds and mammals collected by Pierre Sonnerat on his voyages, between 1786 to 1788.[11] The publication can be assessed here. However, some parts of it are in a foreign language. It is of note that the exact year is uncertain and as a result, some websites state the original description as 1786[12], while some sites state it as 1788 [13] [14] . For the purposes of this species page, the year of the original description will be taken as 1788.

Distribution

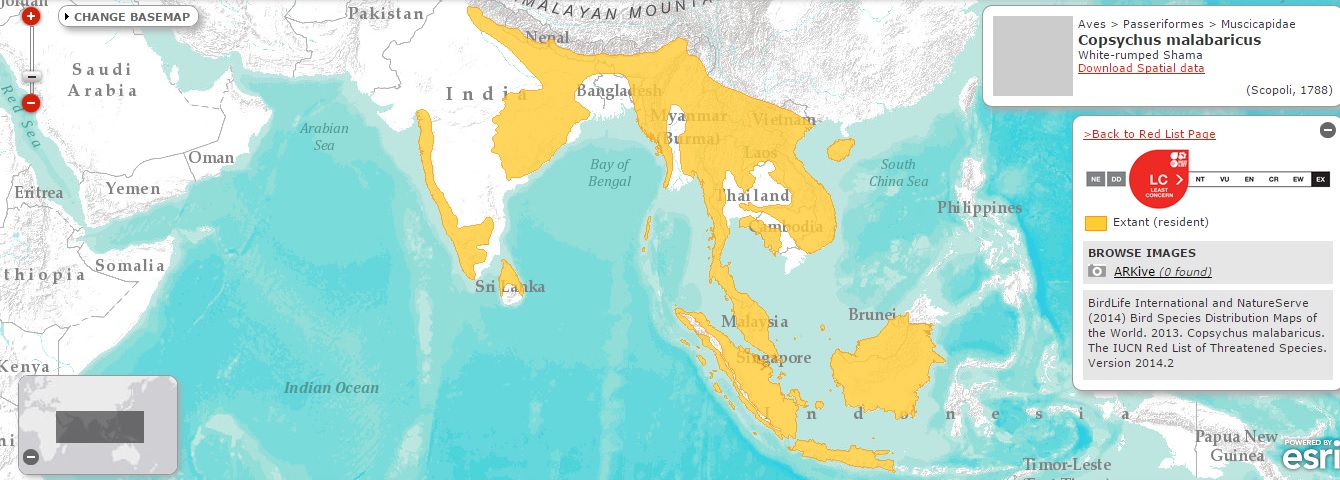

Worldwide

The White-Rumped Shama have an extremely large range[15] , from South-East Asia and the Greater Sunda Islands, to South China and India; where they are native. As a result of deliberate introduction to supplement native fauna, their range was extended even further to the Hawaiian Islands, where they were introduced starting from the 1930s (Kauai in 1931, Oahu in 1940 and Maui in late 1900s)[16]. Their introduction was apparently rather successful[17] .A more specific, non-exhaustive list of areas worldwide is shown below and highlighted in orange in Figure 3[18] :

Bangladesh, Bhutan, Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, Lao People's Democratic Republic, Malaysia, Myanmar, Nepal, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Vietnam, Hawaii (introduced)

|

| Figure 3. Worldwide distribution of the White-Rumped Shama (Hawaii not reflected) (Photo: IUCN) |

Singapore

In Singapore, the White-Rumped Shama are rather rare in the Mainland, but more numerous on the offshore islands, such as Pulau Tekong, Pulau Ubin and Sentosa. The subspecies found in Singapore is C. m. tricolor (For more details, see later section on Taxonomy and Systematics).A more specific, non-exhaustive list of areas in Singapore is given below[19] and reflected in Figure 4:

Bukit Batok Nature Park (Light blue tag), Central Catchment Nature Reserve (Purple tag), Kent Ridge Park (Orange tag), Pulau Ubin (Green tag), Pulau Tekong (Dark brown tag), Sentosa (Red tag), Singapore Botanic Gardens (Yellow tag)

|

| Figure 4. Distribution of the White-Rumped Shama in Singapore (Photo: Lim Pei Wei) |

Description

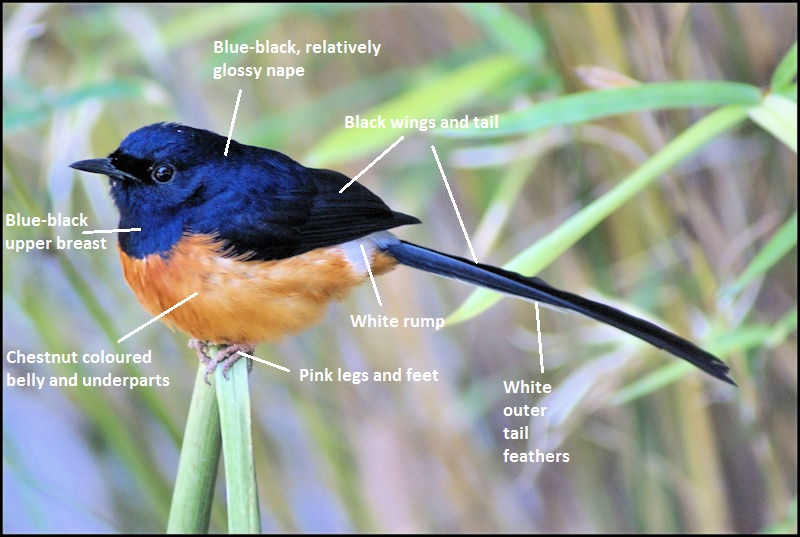

Morphology

Adults:In general, White-Rumped Shama adults have a distinctive and attractive morphological appearance (Figure 5). They have a dark-coloured (blue-black), relatively glossy nape and upper breast. Their bill, wings and tail are black, and they have pink legs and feet. In addition, they have a rufous, or chestnut coloured belly and underparts. Their black tail is extremely long, with white outer feathers, which allow them to change directions quickly [20] [21] . Their most distinctive morphological character, as well as their namesake, is their white rump, referring to the part of the bird's body just before the start of the tail. Significant sexual dimorphism has been observed, and will be elaborated in further detail below.

|

| Figure 5. Overall morphology of White-Rumped Shama adult (Photo: Everton De Melo) |

Males:

Males are more striking, with glossy blue-black head, breast and upperparts. Their underparts is a deep rufous orange[22] . In addition, they are larger, averaging 27cm in length, with a tail of around 18cm long[23] . They resemble that of Figure 5.

Females:

Compared to males, females are duller, with a more greyish-brown colouration. They have a less glossy and more greyish head, breast and upperparts, more-brownish chest and duller rufous-orange underparts [24] [25] . In addition, they are smaller, averaging 22cm in length, with a tail of around 14.5cm (Figure 6)[26] .

|

| Figure 6. Morphology of White-Rumped Shama female (Photo: Tom Grey) |

A summary table of comparison between males and females is given below:

| Gender |

Males |

Females |

| Colouration |

Striking |

Duller |

| Head, breast and upperparts |

Blue-black (Glossy) |

Greyish (Less glossy) |

| Chest and underparts |

Deep rufous-orange |

Brownish, duller rufous-orange |

| Size |

Larger (average 27cm) |

Smaller (average 22cm) |

| Tail length |

Around 18cm |

Around 14.5cm |

Juveniles:

Juveniles have shorter tails and have the greyish- brown colouration of the females, with a more blotchy chest (Figure 7)[27] .

|

| Figure 7. Morphology of White-Rumped Shama juvenile (Photo: Tom Grey) |

Diagnosis

The White-Rumped Shama can be distinguished from the closely-related Oriental Magpie Robin (Copsychus saularis). Both species are two of the most widespread species of the genus Copsychus. Moreover, both species share many similarities, namely, being rare on mainland Singapore, having similar colouration (generally black body, bill, wing and tail), and having similar morphology (long black tail and white outer feathers). The method of differentiating the White-Rumped Shama from the Oriental Magpie Robin is shown in the table below:| Species |

White-Rumped Shama (C. malabaricus)[28][29] |

Oriental Magpie Robin (C. saularis)[30][31] |

||

|

||||

| Legs |

Pink |

Grey |

||

| White Rump |

Present |

Absent |

||

| Bold White Wingbars |

Absent |

Present |

||

| Underparts |

Chestnut-coloured or rufous for both males and females |

White for males and dull grey for females |

||

| Habitat |

Old and thick forests |

Coastal areas and open woodlands |

||

Vocalisation

Song

The most valuable asset of the White-Rumped Shama is their beautiful song, as their songs are not only loud and melodious, but rich in notes and tonal quality as well. It was found that each individual has song elements that are almost exclusively their own private utterances, as such, their songs can be rather varied. They also have elements that are reserved for their partner, serving as a distinct indication to secure the return of the partner as quickly as possible[32] . Their beautiful song is the main contributor to their popularity in the caged bird trade, with their owners entering them into songbird competitions[33] . The White-Rumped Shama are also good imitators of the songs of other birds and sounds, and are widely believed to acquire at least part of their songs by imitation. Apparently, the males are the more consistent and beautiful singers (with a complex, beautiful song), with the females singing short songs only during the breeding season or when in the presence of their male partners. This is because in males, song primarily functions both as a territorial signal and mate-attracting signal[34] . The sound clips provided below showcase the White-Rumped Shama's beautiful yet varied songs.

The video below shows a male White-Rumped Shama singing:

===

===

Call

Male and females often vocalise within their territories. They often call with a harsh 'tschak' or 'tck' while foraging or alarmed by disturbance within their territory. They also use their call to indicate their presence to others [35] . Their call can be listened from the sound clip below:

To listen to more songs and calls of the White-Rumped Shama, click HERE .

Biology

Habitat

The White-Rumped Shama are found in forested areas, in secondary jungle or where there is dense underbrush or thick wood cover[36] . They bathe in pools and streams in the forest in order to maintain their feathers as the feathers undergo wear and tear[37] . Overall, they depend moderately on the forest and they do not avoid human habitats[38] .

Behaviour

The White-Rumped Shama are very shy birds and are more often heard (through their melodious songs and loud, clear calls) than seen. They are mainly active in the morning and evening when they may be rarely spotted in flight or perching on tree branches[39] . In addition, they are extremely territorial, and sing to drive away potential competition. The feeding, nesting, and care of young occur almost entirely within the territory[40] . Within their territory, their gait consists of a mixture of hops and dashes, with an occasional pause and tilting of the head to one side[41] . This is seen in the video below where one can observe the series of hops and the head tilting of the White-Rumped Shama.

Diet

The diet of the White-Rumped Shama consist of invertebrates, specifically insects. They feed on insects including cockroaches, grasshoppers, caterpillars, centipedes and earthworms (Figure 9). They usually pick up their prey from the ground or among bushes using a short, jerky run[42] . They feed on the forest floor during twilight hours[43] .

|

| Figure 9. A White-Rumped Shama holding on to its insect prey (Photo: Joe Yao) |

Reproductive Cycle

White-Rumped Shama are both sexually dichromatic and dimorphic. They generally breed from March to June[44] . Their breeding cycle consists of courtship, nesting and incubation and juvenile care.Courtship:

Males usually pursue the female by positioning themselves above the female, give a shrill call, then flick and fan out their tail feathers. This is followed by a rising and falling flight pattern for both the male and female, and more frequent fanning displays by the male with the tail. Females that do not wish to mate will threaten the male and gesture with their mouth open[45] . This is shown in the video below:

Nesting and incubation:

The nest is usually only built by the female, located within a cavity in a low tree or in the undergrowth, and padded with rootlets and leaves. One egg is usually laid per day, yet all eggs (often in three or four egg clutches) will tend to hatch on the same day during the morning hours. The eggs are white to light green with many reddish-brown spots, and measure approximately 17 by 22 millimeters (Figure 10). Incubation will last between 12-15 days and may be conducted by the female or by both parents[46] . Nest building and egg laying were first recorded in March. Nesting activity then peaked in April and decreased through May, June and July[47] .

|

| Figure 10. Eggs of the White-Rumped Shama, which are light green with many reddish brown spots (Photo: Shama Splash Blog) |

Juvenile care and development:

Both parents participate in feeding the young when they are hatched. Hatchlings are blind and featherless, only opening their eyes after around six days and developing complete feathers after 11 days[48] .

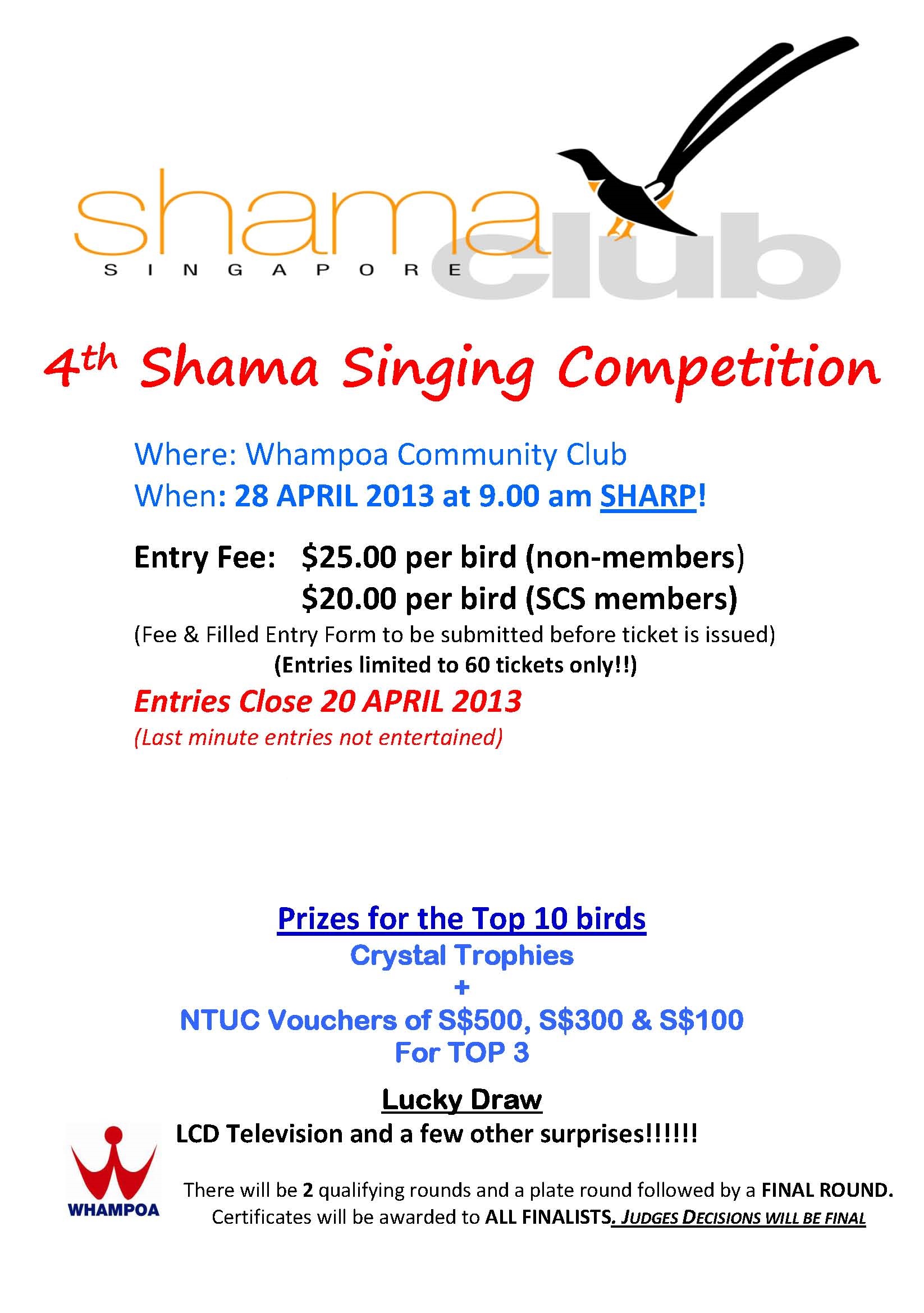

Singapore's caged bird trade

The caged bird trade in Singapore is primarily an import and re-export trade involving several important importers or exporters, together with a domestic retail trade involving a number of small shops. Singapore plays an important role as the main transshipment point for the South East Asian bird trade, in which the largest share of trade passes. The White-Rumped Shama are mainly imported from Malaysia and Indonesia[49] .

In Singapore's caged bird trade, the value of the bird is normally judged by two aspects: physical appearance and the song of the bird. This has resulted in the involvement of songbirds in 90% or more of the bird trade in Singapore. Being deemed as the best songbird in the Malay Peninsula by several ornithologists, longer-tailed White-Rumped Shama will usually fetch a higher price and used for breeding as well. An individual's song quality is also judged on variety and tonal quality. White-Rumped Shama are usually entered into songbird competitions by their owners (such as that shown in Figure 11), with a heavy demand bias towards the male as they are typically the more beautiful singers[50] .

|

| Figure 11. Poster of a Shama singing competition hosted by Singapore Shama Club (Photo: Singapore Shama Club) |

(Poacher fined $500 for trapping wild birds )

http://www.wildsingapore.com/news/20070708/070807-2.htm

(NParks gets tough as poaching is on the rise here)

http://www.wildsingapore.com/news/20070910/071001-1.htm

(Poachers swoop in on feathered wildlife in Singapore )

http://www.wildsingapore.com/news/20070506/070526-4.htm

According to Agri-Food and Veterinary Authority of Singapore's (AVA) regulations, under the Wild Animals and Birds Act, it is an offence for any person to kill, take or keep any wild animal or bird, other than those specified in the Schedule such as mynas, pigeons and crows, without a license. Any person found doing so shall be guilty of an offence and shall be liable on conviction to a fine not exceeding S$1,000 and to the forfeiture of the animal. There is also a hotline for the public to inform AVA at 63257625 if any suspected poaching activities are spotted[52] .

Unfortunately for the White-Rumped Shama, their territorial nature result in their tendency to stay in the same area, thus allowing poachers to locate them easily. This has contributed to their near extinction and rarity on the Singapore mainland[53] .

Conservation status

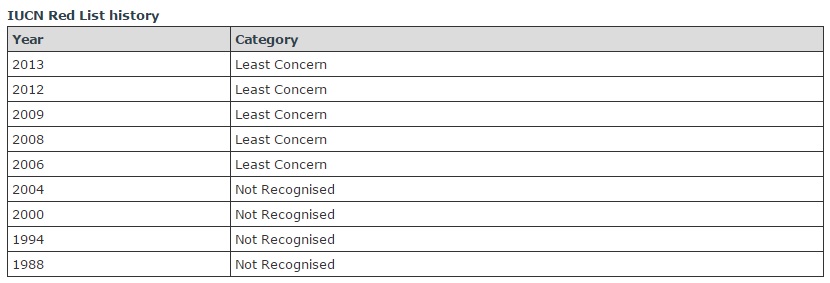

IUCN status

The White-Rumped Shama were classified as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List in 2013, mainly due to their extremely large range. For a more detailed explanation, please refer to http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/22734262/0.

Throughout the years since the White-Rumped Shama has been recognised by IUCN, its IUCN status has always been listed as Least Concern, as shown in Figure 12[54] .

|

| Figure 12. IUCN Red List History of the White-Rumped Shama (Source: BirdLife) |

Threats (Global)

The exact global population size has not been quantified. It is believed that the population is large as the species is described as common in some countries within its global range[55] . However, it is very likely that the global population is currently in decline due to ongoing habitat destruction and over exploitation[56] .

Habitat destruction is mostly caused by selective logging of forests, such as that in biodiversity hotspots like Borneo. This can result in many negative impacts, such as a reduction in the availability of food resources, especially insects. It was found in a study that insects were less abundant overall in logged areas compared to primary forest[57] . This especially impacts species like the White-Rumped Shama whose diet mainly consist of insects. In addition, other significant negative impacts include the loss of breeding sites, loss of suitable nest materials, increase in nest predation and changes in micro-climate[58] .

On the other hand, overexploitation is likely caused by the popularity of the White-Rumped Shama in the caged bird trade and resulted in their population decline to near-extinction in some countries within its global range[59] .

Threats (Singapore)

The White-Rumped Shama is a popular caged bird in Singapore and constantly trapped by poachers, resulting in their rarity on Mainland Singapore. It is believed that they are threatened by illegal trapping[60] . They are still relatively present, however, on the offshore islands such as Pulau Ubin. As this fact is becoming more widely known to the general public, it is worrying whether poachers will change theirpoaching locations to these offshore islands and cause a further decrease in their population in Singapore.

Taxonomy and systematics

Taxonavigation

| Animalia |

| Chordata |

| Aves |

| Passeriformes |

| Muscicapidae |

| Copsychus |

| C.malabaricus |

Subspecies

Due to the broad geographic distribution of the White-Rumped Shama, they exhibit intraspecific plumage variation, resulting in numerous subspecies recognized to account for this variability[61] . According to the Clements Checklist of Birds of the World in 2014, there currently exists 19 subspecies, each with a different native geographic range. Detailed descriptions for each of the subspecies and how they can be differentiated from each other are currently unavailable. The complete list of the subspecies (of native White Rumped Shama) and their respective geographic ranges are listed in Table 1 below[62] :

In Singapore, the subspecies identified was C. m. tricolor[63] . In addition, introduced White-Rumped Shama to Hawaii (Kauai and Oahu) were identified as the subspecies C. m. indicus in 1973[64] .

Table 1. List of C. malabaricus subspecies and their respective geographic range

| Subspecies |

Range |

| C. m. malabaricus |

South peninsular India |

| C. m. leggei |

Sri Lanka |

| C. m. indicus |

Nepal to Assam and North-East India |

| C. m. interpositus |

South-West China to Myanmar, Thailand, Indochina and Mergui Arch |

| C. m. minor |

Hainan (Southern China) |

| C. m. mallopercnus |

Malay Peninsula, Riau Archipelago and Lingga Archipelago |

| C. m. tricolor |

Sumatra, including Java, Banka, Belitung and Karimata Islands |

| C. m. mirabilis |

Prinsen I. (Sunda Strait) |

| C. m. melanurus |

Islands off North-West Sumatra |

| C. m. opisthopelus |

Islands off South-West Sumatra |

| C. m. javanus |

Central Java |

| C. m. omissus |

East Java |

| C. m. ochroptilus |

Anambas Islands (South China Sea) |

| C. m. abbotti |

Bangka and Belitung islands (off Borneo) |

| C. m. eumesus |

Natuna Islands (off Borneo) |

| C. m. suavis |

Borneo (except northern part) |

| C. m. nigricauda |

Kangean Islands and Matasiri I. (Java Sea) |

| C. m. stricklandii |

Lowlands of North Borneo, Labuan, Balembangan and Banggi islands |

| C. m. barbouri |

Maratua Islands (off North Borneo) |

There have been uncertainty throughout the years over whether the subspecies C. m. suavis and C. m. stricklandii hybridize. This has led to taxonomists either lumping the two subspecies together, or recognizing them as distinct subspecies. Through extensive literature review and specimen examination, it has been recognised that C. m. stricklandii should be maintained as a subspecies of C. malabricus, one of the main reasons being that their ND2 (A mitochondria gene) divergence of 2.7% is within the commonly detected range of conspecific passerine taxa[65] .

Type Information

The species was originally described by J.A. Scopoli between 1786-1788 (exact year unknown) in Deliciae Flora et Fauna Insubricae Ticini. (See Nomenclature Section above for more details)[66] .

The type information of The White-Rumped Shama was provided by Museum of Vertebrate Zoology (MVZ) Bird Collection (Arctos) and summarized below[67] :

Location: Museum of Vertebrate Zoology (MVZ), University of California, Berkeley

Catalogue Number: 23517

Sex: Likely to be male

Preparation: Skin

Collector: Harold C. Bryant (Collector Number: 561)

Date collected: 24th July 1913

Location collected: San Francisco

Phylogeny

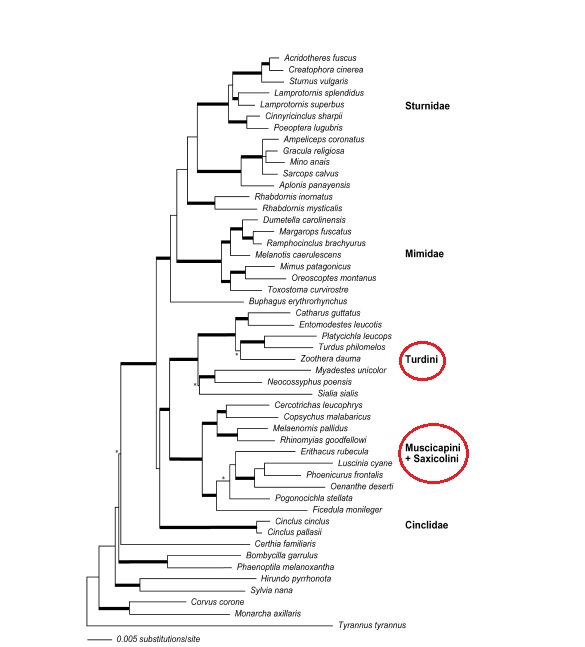

The White-Rumped Shama have been previously classified as being part of the Thrush family (Turdidae), because of its similar gait (a mixture of hops and dashes, with an occasional pause and tilting of the head to one side) with several local species of thrushes[68] . This resulted in its previous naming as Shama Thrush or White-Rumped Shama Thrush[69] .

However, DNA studies have now put them under the Flycatcher family (Muscicapidae)[70] . From Figure 13, we can see that the Turdidae and Muscicapidae Family (circled in the Figure), are separate sister clades. This finding has received strong support, whereby a “thrush-flycatcher” lineage with Turdidae as a sister clade to Saxicolini-Muscicapini (highlighted in Figure 13), has received support through different methods of phylogenetic analysis[71] .

|

| Figure 13. Maximum Likelihood Tree depicting Family Turdini (Turdidae) and Family Muscicapini (Muscicapidae) as separate sister clades (Source: Cibois and Cracraft, 2004) |

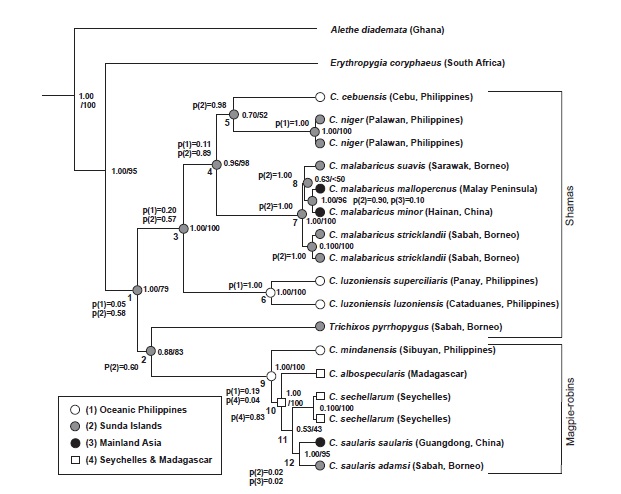

Exploring deeper into the phylogeny of Copsychus shamas, the genus Trichixos appears to be the sister clade of magpie robins (C. saularis), and together they are the sister clade of Copsychus shamas. Within Copsychus shamas, C. luzoniensis is sister to a clade consisting of C.malabaricus, C. niger and C.cebuensis. Within the White-Rumped Shama, C.malabaricus, subspecies C. m. stricklandii is sister to a clade consisting of Western Bornean suavis, Malayan mallopercnus and Hainanese minor (Figure 14)[72] . The tree in Figure 14 reflects the combined gene trees of ND2, Myo2 and TGFβ 2-5.

|

| Figure 14. Phylogenetic tree of some of the subspecies of C.malabaricus (Source: Lim et al., 2010) |

Barcode data

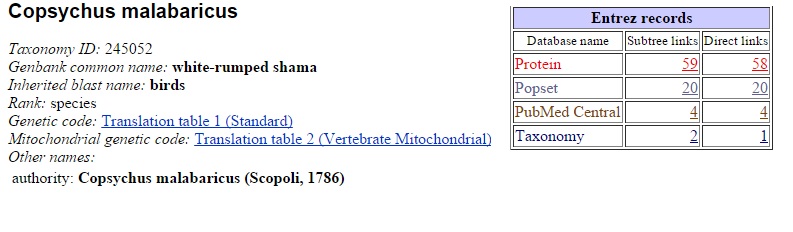

The DNA barcode data summary for the White-Rumped Shama can be found at

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Taxonomy/Browser/wwwtax.cgi?mode=Info&id=245052&lvl=3&lin=f&keep=1&srchmode=1&unlock

A screenshot summarizing the main details (Figure 15) is shown below:

|

| Figure 15. Screenshot of DNA barcode data summary for the White-Rumped Shama (Source: National Center for Biotechnology Information) |

Future possibilities

There seem to be hardly any research conducted on the population distribution and population genetics of the White-Rumped Shama in Singapore. Thus, possible future research can likely investigate whether White-Rumped Shama spotted in the wild are indeed wild birds, or if they are released or escaped caged birds[73] . This is because unfavored or unsold caged birds are often deliberately released into the wild, thus possibly impacting the ecosystem[74] . However, it is uncertain how widespread of a problem it is and this can likely be investigated through such future research.

In addition, the detailed description of each of the subspecies of the White-Rumped Shama and the method of differentiating each subspecies can be investigated through future research, as such information is currently unavailable at the moment and will prove to be very useful.

==

==

Useful Links

White-Rumped Shama on BirdLife International

White-Rumped Shama on Singapore Infopedia

White-Rumped Shama on The DNA of Singapore

References

Lim, K.S., 2010. Report on the 11th Mid-Year Bird Census. Singapore Avifauna 24(5):47-51.

Low, E., 2006. White-rumped shama. National Library Board. URL: http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/infopedia/articles/SIP_1510_2009-04-21.html. Accessed on 3 November 2014.

Encyclopedia of Life, 2012. Copsychus malabaricus, White-rumped shama. URL: http://eol.org/pages/1177973/overview Accessed on 3 November 2014.

Encyclopedia of Life, 2012. Copsychus malabaricus, White-rumped shama. URL: http://eol.org/pages/1177973/overview Accessed on 3 November 2014.

Scopoli. J.A., 1786-1788. Deliciae Flora et Fauna Insubricae Ticini.

BirdLife International, 2013. Copsychus malabaricus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2014.2. <www.iucnredlist.org> Downloaded on 3 November 2014.

Yap, F., 2014. White-rumped Shama in Singapore. URL: http://fryap.wordpress.com/2014/08/08/white-rumped-shama-in-singapore/Accessed on 4 November 2014.

Aguon, C. F., S. Conant, 1994. Breeding Biology of the White-Rumped Shama on Oahu, Hawaii. The Wilson Bulletin 106(2): 311-328.

Low, E., 2006. White-rumped shama. National Library Board. URL: http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/infopedia/articles/SIP_1510_2009-04-21.html. Accessed on 3 November 2014.

ZipCodeZoo.com, 2001. Copsychus malabaricus. URL: http://zipcodezoo.com/animals/c/copsychus_malabaricus/ Accessed on 8 November 2014.

The DNA Of Singapore, 2014. Copsychus malabaricus. Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research. URL: http://lkcnhm.nus.edu.sg/dna/organisms/details/499. Accessed on 3 November 2014.

BirdLife International, 2013. Copsychus malabaricus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2014.2. <www.iucnredlist.org> Downloaded on 3 November 2014.

Nash, S.V., 1993. Sold For A Song: The Trade in Southeast Asian Non-CITES Birds. TRAFFIC International. Cambridge. United Kingdom. 85 pp.