Xylocopa latipes (Drury, 1773)Tropical Carpenter Bee(Hymenoptera: Apidae: Xylcopini)

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

It is big. It is black. It is scary. These are just some phrases that a layperson will describe the largest bee in Singapore, the Tropical Carpenter Bee (Xylocopa latipes) [1]. Despite being one of the largest species of bee in the world, one should not be afraid of its loud, droning hum because they are relatively unaggressive and rarely sting [2].The layperson commonly mistakes the Xylocopa species as Bumblebees of the genus Bombus [1]. However, Xylocopa species have a shiny abdomen which differentiates them from the Bombus species with hairy abdomen.Xylocopa latipes shares many similarities with X. aestuans in terms of foraging, nesting and pollination behaviour—mostly covered by Ng Kai Yi in the species page 'Xylocopa aestuans'. Hence, this page would focus more on the other interaction that X. latipes has with the environment. The page targets insect enthusiasts as well as students in the field of environmental biology and ecology.

2. Diagnosis

Click here to link you to detailed labelling of the different body parts of a bee.Due to its large size (largest bee in Singapore), Xylocopa latipes can be easily distinguished from the other carpenter bees found in Singapore. X. latipes is about the size of a 9 volt battery (Figure 2).

|

| Figure 2: Size comparison between X. latipes and a 9V battery © 2016 G. W. Yong |

2.1. Female comparison

Although not taxonomically fair, but it is generally possible to distinguish the female carpenter bees of Singapore to 2 or 1 species based on thoracic hair colour alone (Table 3). But fair warning, this should only serves as a guide and has to be taken with a pinch of salt. For more detailed species delimitation based on morphology characters refer to section 2.2.| Table 3: All species of carpenter bees (female) in Singapore generally categorised by thoracic hair colour (Images: © 2016 S. X. Chui).Every scale bar length is 10mm. |

||

| Black |

X. latipes |

X. auripennis |

| Blue |

X. caerulea |

X. insularis |

| Yellow |

X. flavonigrescens |

X. aestuans |

| White |

X. dejeanii |

|

| Orange |

X. myops |

|

2.2. Female Diagnosis

The real problem lies when trying to distinguish between X. latipes and X. auripennis because both species look very similar. However, X.latipes is generally larger in size than X. auripennis. Figure 4 presents the key to distinguish the Xylocopa species in Singapore: |

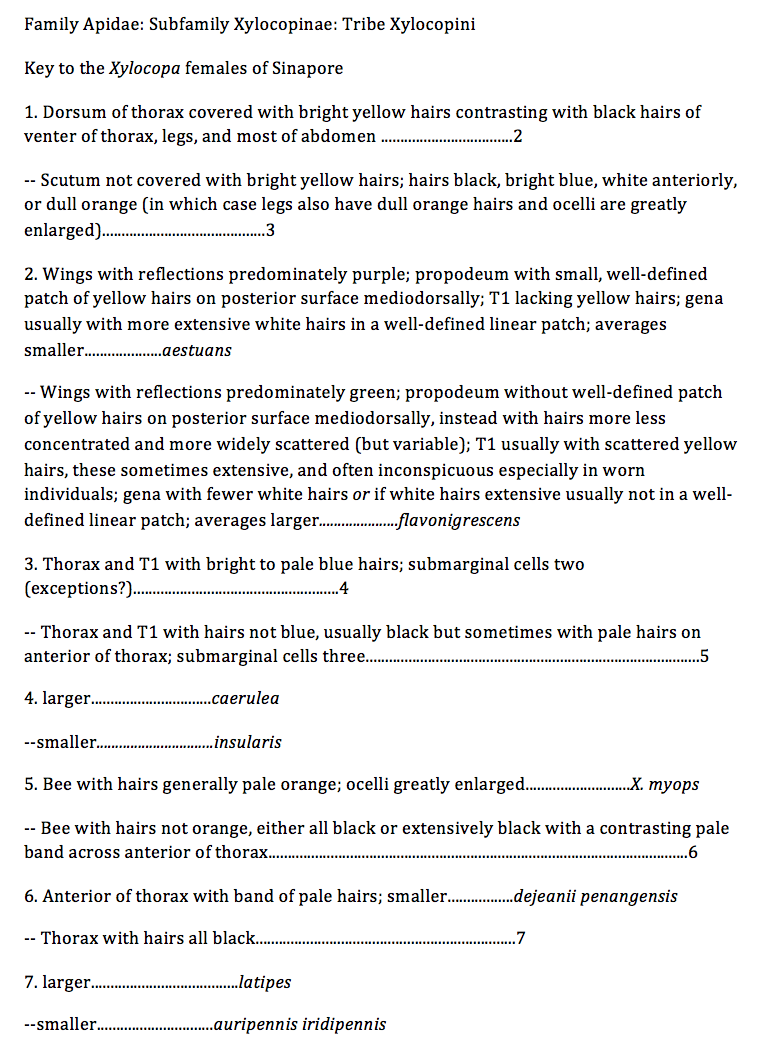

| Figure 4: Key to Xylocopa species in Singapore (contributed by J. S. Ascher) |

To confirm the delimitation of X. latipes and X. auripennis, compare the scutellar beginning of the female thoracic declivity. The thoracic declivity of X. latipes is acute and angular (Figure 5a) while the thoracic declivity of X. auripennis is relatively flat (Figure 5b) [3].

|

|

| Figure 5a: Thorax of X. latipes showing acute declivity © 2016 Y. G. Tan |

Figure 5b: Thorax of X. auripennis showing the relatively flat declivity © 2016 S. X. Chui |

2.3. Male comparison

Like the female Xylocopas of Sin| Table 6: All species of carpenter bees (female) in Singapore generally categorised by thoracic hair colour (Images: © 2016 S. X. Chui). Every scale bar length is 10mm. |

||

| Black |

X. latipes |

|

| Blue |

X. caerulea |

|

| Yellow |

X. flavonigrescens |

X. aestuans |

| White |

X. dejeanii |

|

| Orange |

X. myops |

|

The male X. latipes is easily distinguishable from all other male Xylocopa species in Singapore. The male X. latipes is the only Xylocopa in Singapore with a pair of S-shaped white front tarsi (Figure 7a) that is flattened [4] and is lined with elongated white hairs on the posterior margin (Figure 7b).

|

|

| Figure 7a: Male X. latipes showing front white tarsi © 2016 Y. G. Tan Scale bar length is 10mm |

Figure 7b: White tarsus of Male X. latipes © 2016 S. X. Chui Scale bar length is 1mm |

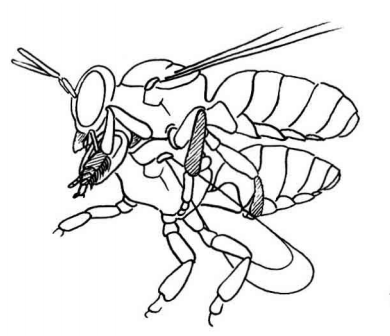

2.4. Male Diagnosis

Presented in Figure 8 are additional morphological characteristics that describe X. latipes. This is to ensure precise delimitation of male X. latipes from the other Xylocopa species from Singapore. |

| Figure 8: Diagnostic description of male X. latipes (contributed by J. S. Ascher) |

2.5. Male VS Female

The males have enlarged eyes which converges above the head (Figure 9b). This is unlike the female, whose eyes do not strongly converge towards the top of her head (Figure 9a). Additionally, the males also have the front white tarsus (Figure 7), which is absent in females. |

|

| Figure 9a: Head of female X. latipes © 2016 S. X. Chui Scale bar length is 1mm |

Figure 9b: Head of male X. latipes © 2016 S. X. Chui Scale bar length is 1mm |

3. Behaviour

3.1. Pollination

Xylocopa latipes diurnal species and is most active from about 8am to 11am in the morning (personal observation, 2016). It is also a generalist when it comes to floral resource use—and will frequent large flowers due to its large body size (Video 10). For more detailed description, click here to go to the 'X. aestuans' page.| Video 10: X. latipes pollinating |

3.2. Buzz pollination

Xylocopa latipes holds on to a flower, shivering its indirect flight muscles at specific frequencies [5], triggering the release of pollen from the anthers of the flowers (Video 11). This is the process of buzz pollination. For more detailed description, click here to go to the 'X. aestuans' page.| Video 11: Buzz pollination explained |

3.3. Nectar robbing

At times, Xylocopa latipes uses its proboscis to cut through the tubular bases of flowers to obtain nectar (Video 12). The plant is not pollinated in the process of nectar robbing, and this behaviour reduces the reward (nectar) for other legitimate pollinators who visits the flower [3].For more detailed description, click here to go to the 'X. aestuans' page.

| Video 12: Nectar robbing explained |

3.4. Mating

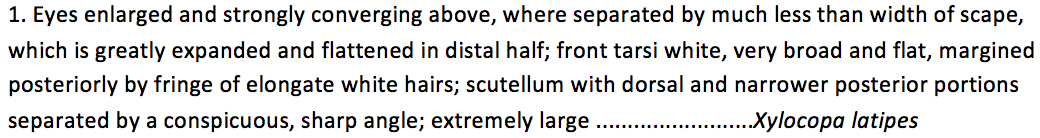

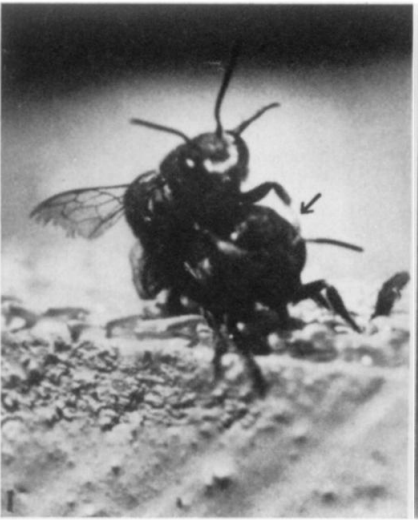

During mating the male X. latipes uses his mid legs to hold onto the female thorax, pressing her wings down in the process (J. S. Ascher, personal communication) (Figure 13). The male then uses its front tarsi with the elongated white hairs to cover the female compound eyes. If the female tries to move he would then stroke her eyes, calming her down. This is similar to other species of solitary bees, like leaf-cutter bees (family: Megachilidae) with similar structures on their front tarsi [6][7]. |

|

| Figure 13a: Male of a Megachile species brushing the compound eyes with his pale tarsus (arrow) during copulation (pending permission [6]) |

Figure 13b: Schematic drawing of the mating behaviour (pending permission [7]) |

3.5. Nesting

Xylocopa latipes utilises wooden beams, logs or hollow bamboo to make their nest [8]. In wooden beams or logs, X. latipes bores a tunnel with 2-6 branches which are half an inch in diameter [9]; in hollow bamboo they use the cut or broken end as the enterance. At one point in time there can be as much as 4 generations in one nest. However, such behaviour is damaging to wooden structures like houses [4], as they weaken the structure. The male does not play a role in constructing or providing for the nest. For more detailed description, click here to go to the 'X. aestuans' page.4. Ecology

4.1. Mites community

|

| Figure 14: Acarinarium of a bee (pending permission [8]) |

There are 7 species of mites associated with X. latipes [10]. However, these mites are

not specific to Xylocopa latipes and can be found on other paleotropical

Xylocopa species. These mites are found either living in the brood cells of the nest of the Xylocopa species or in the acarinarium (Figure 14) of the Xylocopa bees.

There are mites that act as negative selection pressure on the host as they either are kleptoparasites (Horstia virginica; steals food from host) or by killing off the host eggs or larvae possibly consuming it as a resource (Sennertia americana).

Not all the mites are considered to interfere with the development with the host, in fact it was postulated that there is a positive selection for one of the mite species Dinogamasus sp. This genus of mites, feeds on microorganisms that potentially harms the bee larvae and pupa.

There are other mites that have a commensal relationship with the host. One species (Tarsonemus platynopodae) is a fungivore which helps the host to rid fungi from the nest; other species (Cheletophyes sp.) preys on smaller mites.

5. Distribution

5.1. Global

Xylocopa latipes is typically found in the eastern tropical region of the world (Figure 15). The specimen in Germany, Guatemala and Mexico (red pins) is most likely to be erroneous as X. latipes is an eastern tropical species [9][3].| Figure 15: Global distribution of X. latipes (with permission, Discover Life) |

5.2. Local

Generally, X. latipes can be found throughout Singapore and on some islands around Singapore. Figure 16 below depicts the localities where X. latipes has been caught from. However, the map may not be complete as there might be unexplored places with X. latipes sightings.| Figure 16: Local distribution of X. latipes (Source: NUS Insect Diversity Lab) |

6. Taxonomy & Phylogeny

6.1. Taxonomic classification

| kingdom |

Animalia |

| Phylum |

Arthropoda |

| Class |

Insecta |

| Order |

Hymenoptera |

| Superfamily |

Apoidea |

| Family |

Apidae |

| Tribe |

Xylocopini |

| Genus |

Xylocopa |

| Subgenus |

Platynopoda |

| Species epithet |

latipes |

6.2. Validity of subgenus Platynopoda

Michener (2007) have synonymised the subgenus Platynopoda into the subgenus Mesotrichia Westwood, 1838. However, this is believed to be incorrect. Phylogenetic analysis has shown that the subgenus Mesotrichia is paraphyletic to the subgenus Platynopoda [4].It was further postulated that both subgenus were separate but closely related lineages [4]. This is evident from morphological evidence. Modifications to the first pair of legs were present in males from Platynopoda, while the modification were on the second pair of legs in Mesotrichia. The non-overlaping and apomorphic modification, within their own lineage, suggest the presence of 2 separate but closely related lineages.

Hence, this evidence suggest that Platynopoda is a subgenera on its own. However, further comprehensive phylogenetic analysis is required to fully understand the status of these lineages.

6.3. Phylogeny

Leys et al. (2002) investigated which phylogenetic analysis is the most robust to compare between different subspecies of carpenter bees. The 3 phylogenetic analysis used in the study were maximum parsimony, maximum likelihood and Bayesian analysis. The linearised Bayesian tree (Figure 17c) has been proposed to be the most reliable for phylogenetic analysis [11]. However, Suzuki et al. (2002) has proved that posterior probabilities used in Bayesian analysis is unusually high, hence the relationship values between the subspecies of carpenter bees might be inflated by the Bayesian approach [12]. |

| Figure 17: X. latipes is represented by the Platynopoda. Brevineura is used an out group for (a) and (b). (a) Maximum parsimony tree, node numbers are encircled, bootstrap values plotted above the branches. (b) Maximum likelihood tree. (c) Linearised Bayesian tree, posterior probabilities as branch support plotted above branches. (pending permission [11]) |

The high posterior probabilities seen in Figure 17 is due to the same relationship branches appearing in most of or all of the sampled trees used to construct the consensus Bayesian tree [12]. This is caused by the Markov chain Monte Carlo computation sampling the same set of trees multiple times, resulting in an over liberal posterior probabilities.

On the other hand, the use of bootstrap values in the maximum parsimony tree as support for phylogenetic analysis is more appropriate. This is because the bootstrap values treats the original sequences as single evolutionary event realised with errors that occur at random probabilities [12]. Hence, bootstrap values are more conservative and more appropriate as errors tat occur at random probability is always present in original sequences.

Presented in the same paper by Leys et al. (2002) is the maximum parsimony tree (Figure 17a) and maximum likelihood tree (Figure 17b) which might be a viable alternative to the linearised Bayesian tree. The common themes in all three trees are that the genus Xylocopa is further separated into 3 clades—Ethiopian (made up of African and Oriental clade), Xylocopa s. l. clade (geographically diverse group) and a American clade.

The 3 clade this is supported by all 3 trees just indicates that there were 3 common ancestors, 1 for each clade. These 3 common ancestors went through many speciation events to give the many subgenera seen in the trees. Additionally, based Figure 10c, the common ancestor for the Xylocopa S. I. clade begun to speciate first, followed by the common ancestor in the American clade and Ethiopian clade.

Perhaps, the common ancestor of all 3 clades was a global species very much like the Xylocopa S. I. clade. Then one of the individuals of the common ancestral species decided to nest and propagate within the new world (America) around 35 million years ago, and another decided to nest and propagate within the old world (Africa + Oriental) around 30 million years ago. This could possibly have given rise to reproductive isolation, and the common ancestral lineage began to split into 3 distinct lineages, producing the 3 clades that we see now.

On a side note, X. auripennis (other black Xylocopa species found in Singapore) is the representative for the subgenus Biluna, which was found to be basal to all the other subgenus with strong support from both the maximum parsimony and Bayesian analysis.

6.4. Type information

| Type material |

Male holotype |

| Type locality |

Anjouan island (Union of Cosmoros) |

| Type repository |

Drury collection (London Natural History Museum) |

| Collector |

Dru Drury |

| Year collected |

1773 |

| Type First mentioned |

D. Drury, 1773. Illustrations of natural history [13] |

| Original name |

Apis latipes Drury, 1773 |

| Synonyms |

Apis gigas DeGeer, 1773; Mesotrichia latipes (Drury, 1773); Xylocopa (Koptortosoma) latipes (Drury, 1773); Mesotrichia (Platynopoda) latipes (Drury, 1773); Xylocopa (Platynopoda) latipes (Drury, 1773); Mesotrichia (Platynopoda) latipes basiloptera (Cockrell, 1917) |

The type information is The locality is most likely to be erroneous. X. latipes is an "eastern species" [9], hence there is a high chance there might be a mistake in sorting or recording the locality.

7. Refrences

[1] Tan, K. H. (2012). Bees, Wasps and Ants. Sgwildanimals.blogspot.sg. Retrieved 4 November 2016, from http://sgwildanimals.blogspot.sg/2012/10/bees-wasps-and-ants.html[2] Seifert, D. (2013). Going Places Singapore - Creatures of the Little Red Dot. Going Places Singapore. Retrieved 6 November 2016, from https://www.goingplacessingapore.sg/more/Top5/2013/Top5Animals

[3] Michener, C. (2007). The bees of the world (1st ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

[4] Mawdsley, J. (2015). An annotated checklist of the large carpenter bees, genus Xylocopa Latreille (Hymenoptera: Apidae), from the Philippine Islands. Oriental Insects, 49(1-2), 47-67.

[5] Buchmann, S. L., & Hurley, J. P. (1978). A biophysical model for buzz pollination in angiosperms. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 72(4), 639-657.

[6] Batra, S. W. T. (1978). Aggression, Territoriality, Mating and Nest Aggregation of Some Solitary Bees (Hymenoptera: Halictidae, Megachilidae, Colletidae, Anthophoridae). Journal Of The Kansas Entomological Society, 51(4), 547-559.

[7] Wittmann, D. & Blochtein, B. (1995). Why males of leafcutter bees hold the females' antennae with their front legs during mating. Apidologie, 26(3), 181-196.

[8] Batra, S. W. T. (1977). Bees of India (Apoidea), their Behaviour, Management and a Key to the Genera. Oriental Insects, 11(3), 289-324.

[9] Jardine, W. (1833). The naturalist's library. Edinburgh: W.H. Lizars.

[10] OConnor, B. (1993). The mite community associated with Xylocopa latipes (Hymenoptera: Anthophoridae: Xylocopinae) with description of a new type of acarinarium. International Journal Of Acarology, 19(2), 159-166.

[11] Leys, R., Cooper, S., & Schwarz, M. (2002). Molecular phylogeny and historical biogeography of the large carpenter bees, genus Xylocopa (Hymenoptera: Apidae). Biological Journal Of The Linnean Society, 77(2), 249-266.

[12] Suzuki, Y., Glazko, G., & Nei, M. (2002). Overcredibility of molecular phylogenies obtained by Bayesian phylogenetics. Proceedings Of The National Academy Of Sciences, 99(25), 16138-16143.

[13] Drury, D. (1773). Illustrations of natural history. Wherein are exhibited upwards of two hundred and twenty figures of exotic insects, according to their different genera; very few of which have hitherto been figured by any author, being engraved and coloured from nature, with the greatest accuracy, and under the author's own inspection, on fifty copper-plates. With a particular description of each insect: interspersed with remarks and reflections on the nature and properties of many of them. By D. Drury. To which is added, a translation into french. Vol. II. London: Printed for the author, and sold by B. White, at Horace's Head in Fleet-street. 1773.