Left: Xylotrupes gideon, adult male. Image by Bernard Dupont, used under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial License. Right: Male X. gideon fighting. Image by Uthen Kamsurin (permission pending)

Left: Xylotrupes gideon, adult male. Image by Bernard Dupont, used under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial License. Right: Male X. gideon fighting. Image by Uthen Kamsurin (permission pending)Overview

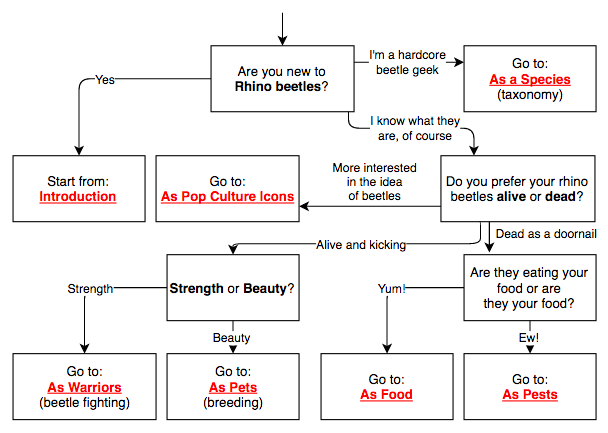

Below is a guide through my species page. If you're a hardcore beetle lover, or maybe just really bored, you are free to read this page from top to bottom. If not, you may use the flowchart below to help you find the section you're interested in, and click the link in the table of contents to arrive at your desired destination.Table of Contents

Introduction

What is a rhinoceros beetle?

The term rhinoceros beetle, or rhino beetle for short, is commonly used to refer to any kind of horned beetle, and most often refers to species from the subfamily Dynastinae (a majestic and fitting name indeed). The Dynastines are one of the most recognisable groups of beetles, due to their relatively large size and the massive facial horns present in many species (For more diagnostic characters, see As a Species). These signature horns are usually only present in adult males, and often used for macho man-to-man battles for honour and the hands of pretty beetle ladies[1] [2] [3] [4] . As to why they're called Rhinoceros beetles, it should be pretty obvious unless you have no idea what a Rhinoceros looks like.

Strength

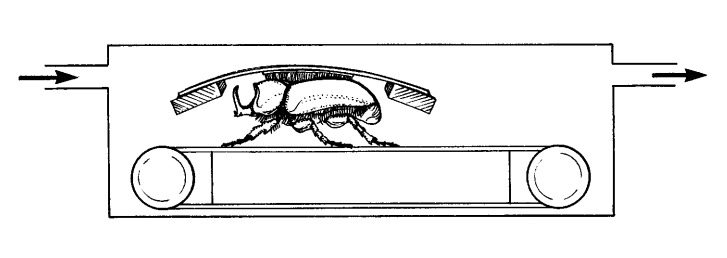

Rhinoceros beetles are famous for their purported power, with anecdotal accounts of ridiculously impressive feats strength. An entry in the Guinness Book of World Records claims that the strongest animal was a rhinoceros beetle that could support 850 times its body mass[5] . More credibly, scientific investigation that - in all seriousness, involves beetles carrying little dumbbells while walking on tiny treadmills - found that dynastine beetles could still move with a load 100 times its body mass, and could sustain regular walking speed with a load 30 times their body mass[6] . This means that the beetles are able to move heavy loads with great effeciency, such that investigating scientists are unsure about how it is possible with existing knowledge of biomechanics and metabolic costs[6]!

VS Stag beetles

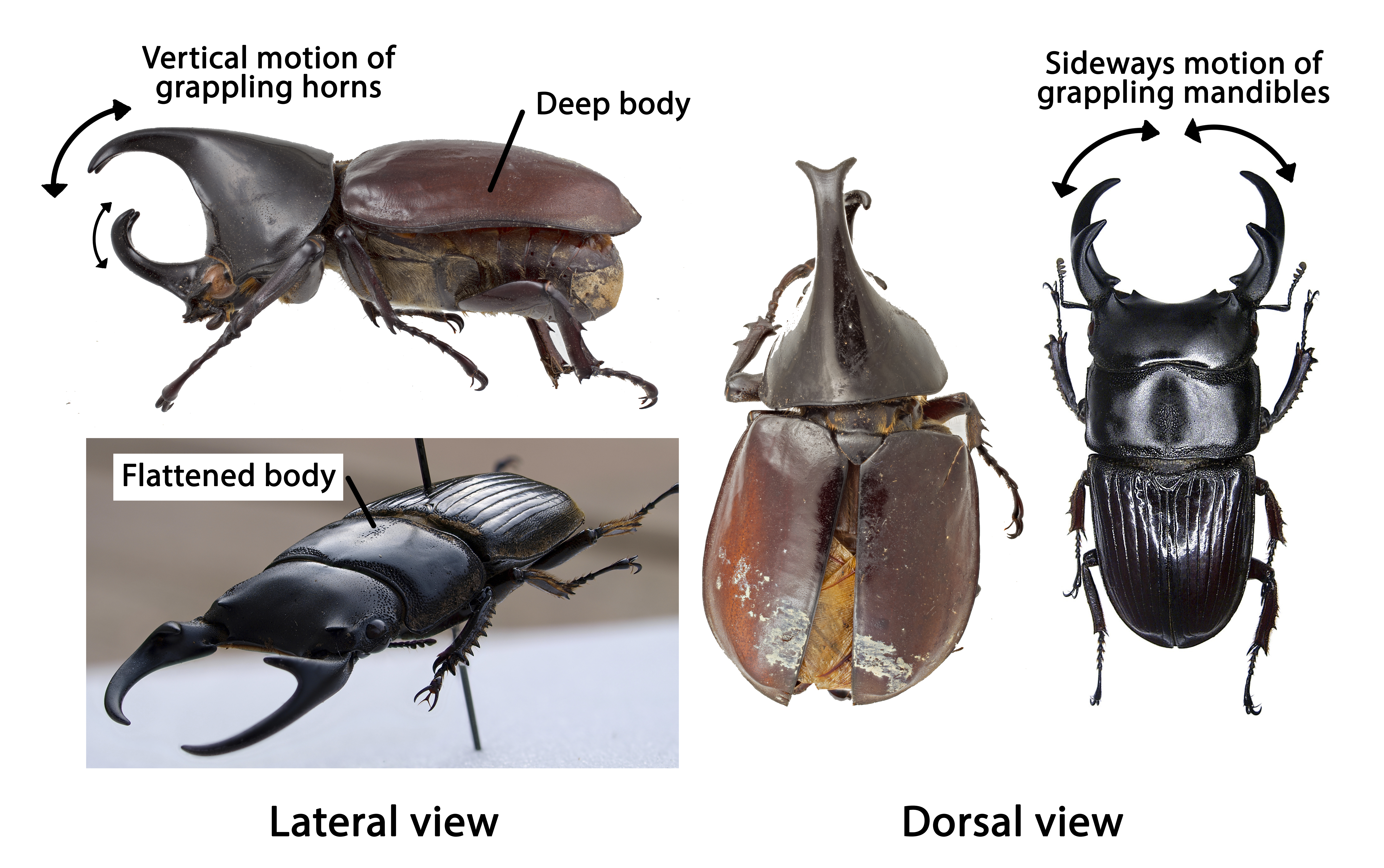

Quite often, rhinoceros beetles are confused with stag beetles (Family Lucanidae) by the layperson, as both are usually portrayed with large horn/antler-like head ornaments used for fighting. However, the grappling ornaments (antlers) of stag beetles are their enlarged mandibles (mouthparts), while the rhino beetles employ the use of their facial and thoracic horns in combat, and do not use their mouths to fight (which is admittedly a lot less gross). Because the rhino beetle horns and stag beetle antlers move along perpendicular planes, they happen to interlock nicely when facing off against each other, rhino and stag beetles are often pitted against each other in the popular japanese beetle fights. Another noticeable difference between the two - while rhino beetles have deeper, rounder bodies like sausages, stag beetles are dorsoventrally flattened like pancakes. These differences are denoted in the pictures below.

As Warriors

Rhinoceros beetles are also famous for their fighting ability. In Japan, rhino beetles are known as 'kabutomushi', which when translated means 'helmet bug', supposedly from the way the beetles' horns resemble the ornaments on samurai helmets (kabuto).

Mating

Female rhino beetles are sexy and they know it, and they usually just sit atop trees, wafting their pheromones to get the boys to come to them. More often than not, multiple guys will be attracted to a single female, and they land on a tree, ascending in search of her. This becomes a battle to the top, and males that encounter each other on the tree grapple each other and engage in wrestling matches, in which the loser is lifted off the tree and tossed to the bottom, having to start his climb from scratch.If beetle horns and size are so important in getting to reproduce, one would expect only the largest and strongest males to survive, but reality is never as we expect. The brown rhinoceros beetles have male morphs that vary a lot in size of both the body and the horns, where smaller males have correspondingly smaller horns. But how do these pretty boys get around the alpha males and get to pass on their genes such that small size remains in the gene pool?

While the benefits of smallness is still relatively understudied for dynastid beetles, studies with the horned, Onthophagus dung beetles[7] have proposed the possibility of sneak mating, where effeminate males fool the buff alpha males into thinking that they're female, thus getting around them without direct confrontation (in which they would most certainly lose) in order to mate with the actual females - with the large males none the wiser!

Beetle fighting

In Thailand, the brown rhino beetle is known as 'Kwang', and betting on beetle fights is a popular past time, especially among men. The sport has recently been outlawed in the state[8] , though there are still hidden beetle fighting rings. Head on to this site for great photos and descriptions of how the beetle fights work!Underground beetle fight club in Chiang Mai, Thailand. Obtained from YouTube under Fair Use guidelines.

Selecting the best fighters for battle. Video by Daniel Ambuehl, obtained from YouTube under Fair Use guidelines.

As Pets

Beetle breeding is big business, especially in Japan and Thailand, where beetles are not only used for fighting but also often kept as pets. Some individual beetles can even be sold for as much as a thousand USD!Beetle breeding at the Siam Insect Zoo. Video by Daniel Ambuehl, obtained from YouTube under Fair Use guidelines.

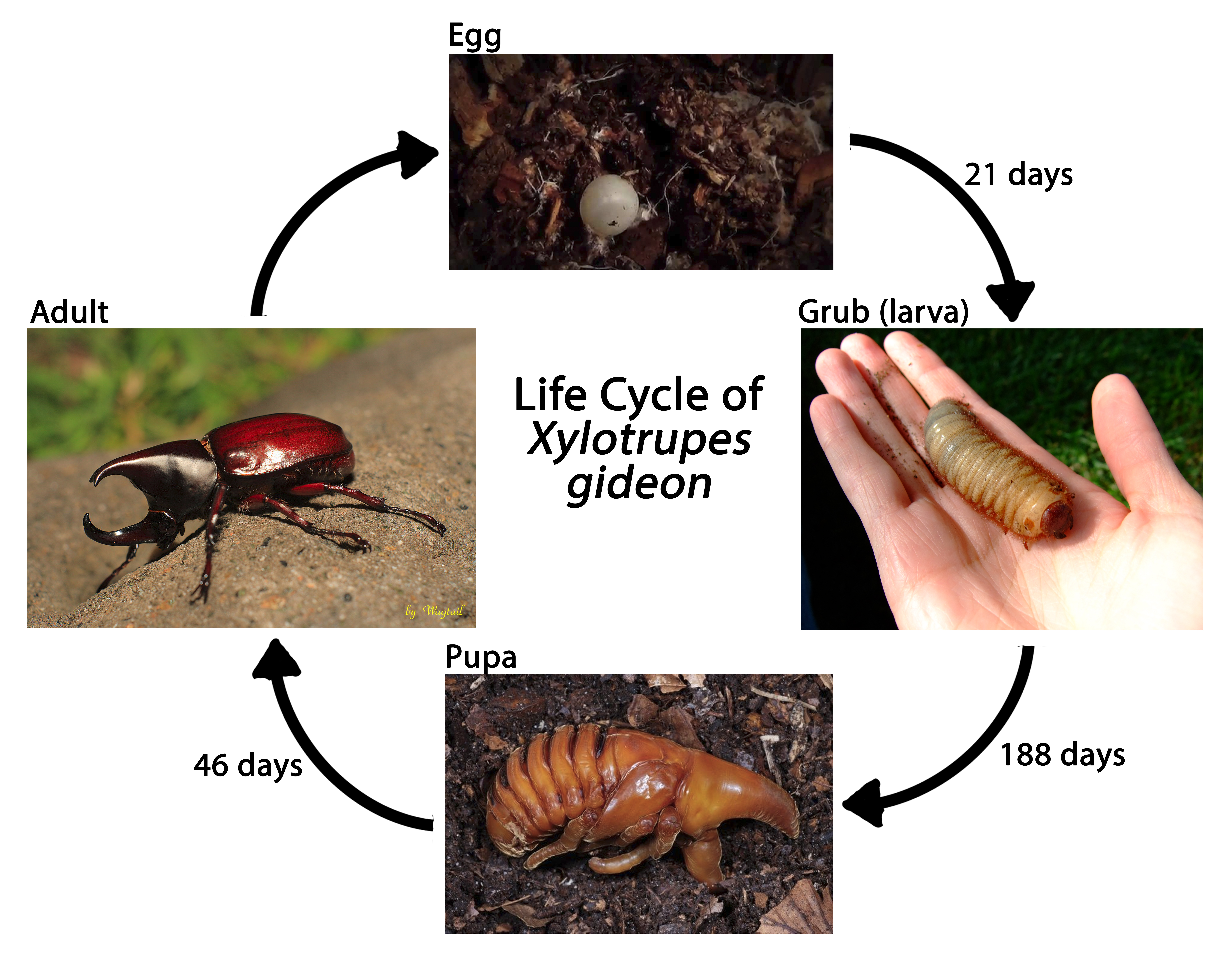

Before embarking on a journey with your pet beetle, one should first understand the life cycle of the beetle.

Life cycle

As a beetle, rhino beetles undergo complete metamorphosis[9] [10] . Female X. gideon lay an average of about 55 eggs [cite Bedford, 1975] in rotten leaves, sawdust or decaying wood[11] . As larvae, the beetles spend a lot of time in nutrient-rich soils and decaying wood, where they pupate for about 46 days before emerging as adults[12] . Adults live for about 90 - 102 days in captivity (Bedford, 1975).

As Food

Entomophagy is the sciencey word for eating bugs, and this new trend is taking the world by storm.In Laos and Thailand, Xylotrupes gideon is one of the species that is eaten by locals, both grubs and adults. It is known as 'Maeng kee noon' in Thai, and 'Mang kwang' in Lao . In Thailand, the beetles are usually wok-fried and seasoned with sauce and pepper powder, to be consumed as a snack food on its own or with beer.

The eating of insects has always been part of Southeast Asian culture (Bristowe, 1932). More recently, entomophagy has become recognised in the west as the future of food, being relatively sustainable and high in nutritional value. There is an exotic selling point as well, and the two factors have contributed much to the fried insect economy. Business is gaining so much traction that companies have started exporting edible insects from Thailand.

The beetles that are imported come boiled and dehydrated instead of fried, and are actually pretty difficult to eat. The exoskeleton is really tough, and the sharp spines on the legs threaten to make your gums bleed. Definitely not for the faint-of-heart!

Eating a female X. gideon. Video by Sean Yap, with permission from persons portrayed.

Interestingly, in areas such as plantations where X. gideon has become a pest species, local tribes have been encouraged to eat them as a possible way of controling the beetle population (Wongdao & Black, 1987).

As Pests

Throughout their range, X. gideon is a known pest species that targets palms such as coconut, but sometimes also goes for the bark of fruit trees (Wongdao & Black, 1987).It is known to feed on newly opened coconut inflorescences and the undersurface of frond midribs, causing the distal portion to break and hang down, affecting the survivability of coconut trees[13] . Apart from tree bark, X. gideon can also attack fruits such as guava[14] , apples and pears (Wongdao & Black, 1987). It is generally regarded as a minor pest though, and is not feared as strongly as its cousin, Oryctes rhinoceros.

As Pop Culture Icons

Japan is crazy about insects, particularly beetles, and a popular trope in television and gaming series and franchises is the 'Japanese Beetle Brothers' trope, where characters designed to resemble rhinoceros beetles and stag beetles are often portrayed as allies or rivals.- Type A: Allies. Usually introduced at the same time, constantly work together and are seldom seen apart. Often either partners or brothers.

- Type B: Rivals. They can't stand each others' guts, constantly butt heads and at times are on opposite sides.

- Type C: Coincidental. This is the rarest of the three types, and occurs when just by chance, a rhino beetle and a stag beetle exist in the same fictional universe, much like their real-life counterparts.

Heracross is rhino beetle Pokemon with the Bug/Fighting type category, a reference to real life beetle fighting. It does share a universe with the stag beetle Pokemon Pinsir, but they do not interact significantly and are thus a type C beetle brothers.

Kabuterimon (rhino beetle) and Kuwagamon (stag beetle) from the Digimon franchise are a classic case of Type B, where the two fight every time they meet.

Kabuterimon and Kuwagamon. Official artwork by Bandai, used in accordance with Fair Use guidelines.

Kabuterimon and Kuwagamon. Official artwork by Bandai, used in accordance with Fair Use guidelines.In the live action series Kamen Rider Kabuto, the red rider Kabuto (rhino beetle) and the blue rider Gatack (stag beetle) start out as rivals but soon become fast allies, exemplifying type A.

As a Species

The Brown rhinoceros beetle (Xylotrupes gideon)

Appearance

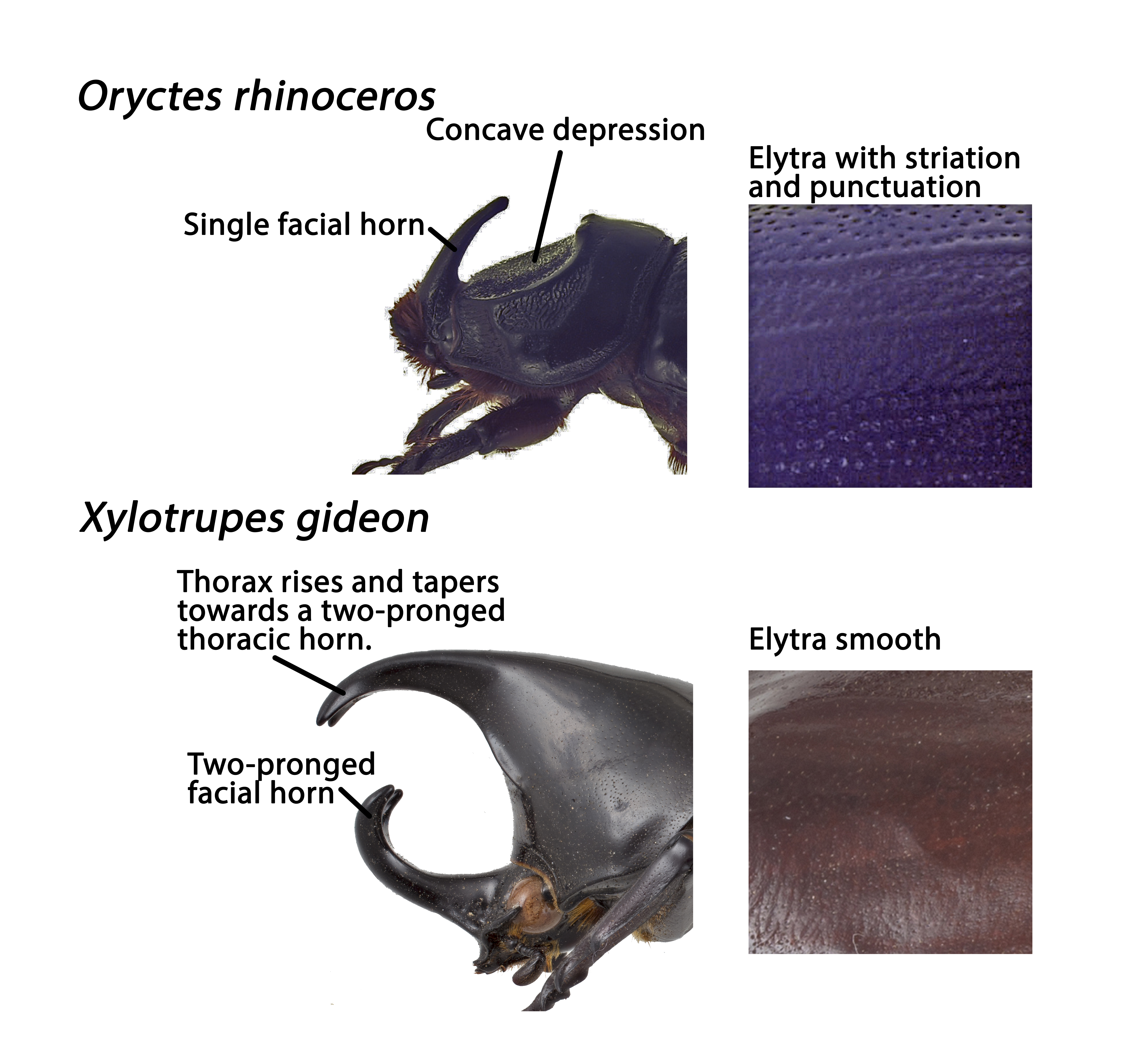

Like its common namesake, this species is largely brown colour, though variation exists between individuals, with some so dark they look almost black. The elytra (hardened forewings that protect the flight hindwings) are relatively smooth and without punctures. These are large beetles, with sizes ranging from about 35 - 70mm for most individuals[15] . Large, bifurcate (two-pronged) horns are present in adult males, but absent in females.

Adult male major and minor Xylotrupes gideon to scale. Major is 60mm in length, minor is 38mm. Image by Sean Yap, specimen collected by Max Khoo De Yuan.

Type Specimen

The type specimen for Xylotrupes gideon resides in the Linnaean Collections of the Linnaean Society of London. It is a male individual labelled with the basiosynonym name, Scarabaeus gideon. The label suffers from a real information deficit. Also, the poor specimen appears to have lost his head.

How to identify - diagnosis

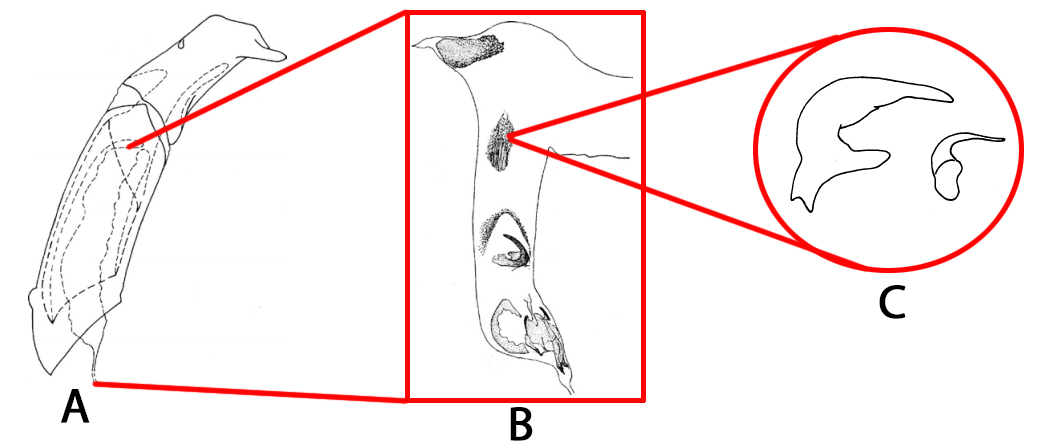

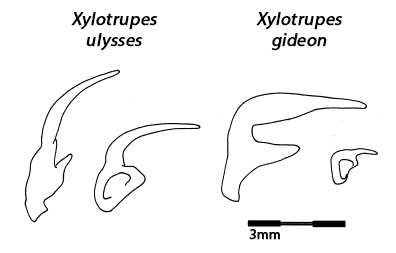

Xylotrupes species are pretty difficult to tell apart from external morphology, and often dissection of genetalia is required.The raspula is a sclerotized piece in the internal sac of the male genitalia of a beetle. The position of this part of the genatilia is shown in the diagram below.

The following are characters with which to diagnose Xylotrupes gideon: Raspular autapomorphs include a very strongly angled right raspula; a very large right raspular bulb; a very long right raspular process originating on the mesal aspect of the raspula and upon which the left raspula is articulated distally; downward reflection of the left raspular cup; the very small size of the left raspula; the median lobe of the aedeagus with lyriform distal invagination. The diagrams below show the difference in shape of the raspula from a closely related species with a small range overlap, Xylotrupes ulysses.

In Singapore

Xylotrupes gideon is found throughout Southeast Asia, including Singapore. In Singapore, this species is easily recognisable as one of our largest beetles, and the largest horned species. The only other horned dynastine beetle in Singapore is Oryctes rhinoceros, which is a basically a smaller, less impressive cousin of X. gideon.

Presented below are some recognisable differences between the two species.

Distribution

Xylotrupes gideon can be found throughout South and Southeast Asia, as well as northern Oceania.

Habitat

Xylotrupes gideon is usually found in forested areas, as well as in palm plantations where it is considered a pest[17] [18] [19] . (For more detail, jump to As a Pest)In Singapore, this species is now relatively uncommon, and sightings are sporadic and random. They sometimes end up in peoples' homes at night, attracted by artificial lighting.

Classification

Warning: Here onwards is where things get pretty technical.Xylotrupes gideon was first described by Linnaeus in 1767 as Scarabaeus gideon, before Hope established Xylotrupes as a genus in 1837 with Scarabaeus gideon as the type[20] . Xylotrupes was one of the 10 recognised genera from the Dynastini tribe in Endrodi (1985), but has since been determined to be inadequately diagnosed and has been re-diagnosed in 2003 by Rowland.

The genus Xylotrupes can be differentiated from other members of tribe Dynastini via its unique apomorph of the constitution of the right raspula as a single large spine [cite Rowland]. Also, only Xylotrupes has the following character combination in this tribe: Apically bifurcate pronotal and cephalic horns, with the pronotal horn the same size or longer than the cephalic horn in major males.

The higher classifications, synonyms and subspecies of Xylotrupes gideon according to the latest revision by Rowland are listed below.

Higher Classification

- Kingdom Animalia (Animals)- Phylum Arthropoda (Arthropods)

- Subphylum Hexapoda (Hexapods)

- Class Insecta (Insects)

- Order Coleoptera (Beetles)

- Suborder Polyphaga (Water, Rove, Scarab, Long-horned, Leaf and Snout Beetles)

- Superfamily Scarabaeoidea (Scarab, Stag and Bess Beetles)

- Family Scarabaeidae (Scarab Beetles)

- Subfamily Dynastinae (Rhinoceros Beetles)

- Tribe Dynastini

- Genus Xylotrupes

- Species gideon

Synonyms

Sometimes, different names are assigned to the same species. This usually happens when a scientist describes a species that has already been described earlier, perhaps unaware of the existing name, or mistaking a morphological variant within the species as a new species. In such a case, the earlier name is treated as the accepted senior synonym, while all names that come after it are considered junior synonyms and generally should not be used. Synonyms can also be the original name of the species when it was first described, that may no longer be correct to use if the species has been transferred to another genus afterwards. This is that case with the name Scarabaeus gideon, the name that Linnaeus first gave the species when it was described in 1767. Since the species has been transferred to the genus Xylotrupes, the name Scarabaeus gideon should no longer be used.Xylotrupes gideon is a species with a relatively large number of synonyms. This is partly due to the fact that it was also known by the genus Scarabaeus for about 70 years, a time span that allowed for the creation of numerous synonyms under that genus name. This list of Scarabaeus synonyms add on to the list of synonyms under the genus Xylotrupes. Xylotrupes gideon is also a relatively charismatic species with many interactions with humans as pests or as a part of local culture, and is likely to get much attention from beetle workers. This, coupled with the fact that some subspecies of X. gideon show significant intraspecific morphological variation[21] , especially between males, could have lead to higher frequency of workers wrongly describing X. gideon individuals as new species. A list of synonyms for this species is listed below.

Scarabaeus gideon Linnaeus 1767

S. oromedon Drury 1770

S. phorbanta Olivier 1789

Geotrupes dentatus Wever 1801

S. Scorticum Voets 1806

S. simson Voets 1806

S. nimrod Voets 1806

S. furciger Voets 1806

S. alcibiades Dejean 1833

Xylotrupes beckeri Schaufuss 1885

X. beckeri var. metzeneri Schaufus 1887

X. inarmatus Sternberg 1906

X. gideon gideon Minck 1920

X. sumatrensis Minck 1920

X. borneensis Minck 1920

X. bourgini Paulian 1945

X. gideon beckeri Endrodi 1951

X. gideon sumatrensis Endrodi 1951

X. gideon borneensis Endrodi 1951

Subspecies

While different websites have different lists of X. gideon subspecies, Rowland asserts that material of this widespread species has not yet been sufficiently examined to support a comprehensive subspecific classification. In Singapore, the local subspecies is likely to be Xylotrupes gideon beckeri (Rowland, 2003).Phylogeny

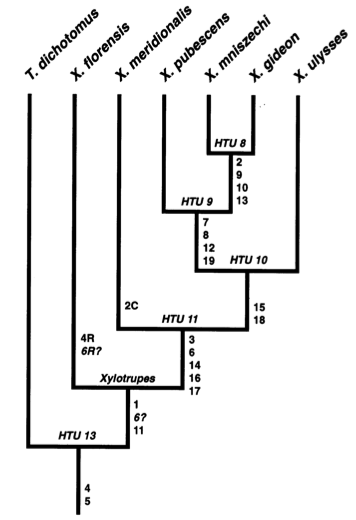

Phylogeny within Xylotrupes

A phylogenetic study of the genus Xylotrupes exists, taking into account only morphological characters (Rowland, 2003). Characters used in the construction of this phylogeny include the length of pronotal (thoracic) horn relative to the cephalic (face) horn, the position of the cephalic horn tooth, number of mandibular teeth, and raspula shape. The tree below was obtained, showing the proposed relationship between X. gideon and other species from the genus Xylotrupes, with a Trypoxylus species as the outgroup as Trypoxylus has been found to be the sister group to Xylotrupes.

Rowland's phylogenetic analysis shows that only two apomorphs (derived characters), both in the raspula, distinguish Xylotrupes from other dynastine genera. The assumed monophyly of the genus however, is supported by the combination of other characters.

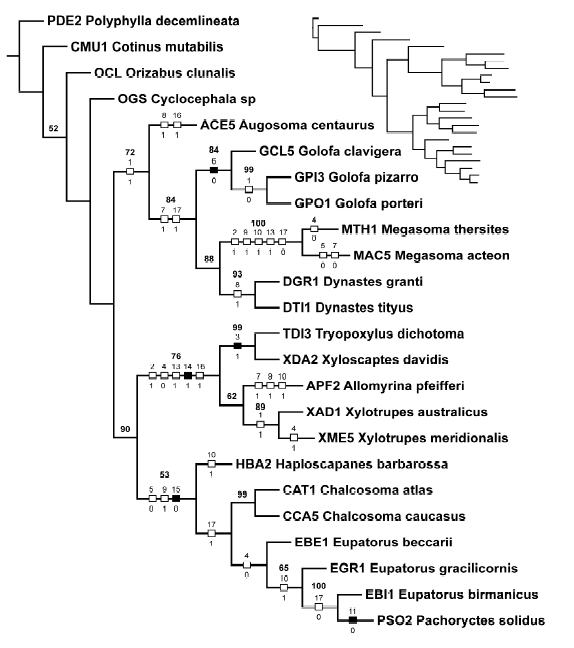

Phylogeny within tribe Dynastini

Rowland and Miller have more recently presented the first inclusive phylogenetic analysis of the Dynastini tribe of giant rhinoceros beetles, which contains the genus Xylotrupes[22] . Twenty species representing each genus within the tribe were included as ingroup taxa for the analysis, which includes morphological, biogeographical and molecular data.Morphological characters used in this analysis include mandible incisor denticulation (how toothy the mandibles are), the presence of cephalic and pronotal horns in different arrangements, presence of sexual dimorphism in the legs, shape of raspulae, and colour of dorsal integument.

For the molecular analysis, four genes were sequenced - Cytochrome c oxidase II (COII), 16S rRNA (16S), histone III (H3) and arginine kinase (ArgKin).

The phylogeny was estimated using a combined equal-weights parsimony analysis using the program NONA (Goloboff 1995[23] ) as implemented by WinClada (Nixon 2002 [24] ) using the heuristic command settings “hold 10000”, “mult*100”, “hold/40” and “multiple TBR + TBR”. Bootstrap values were used to measure branch support. These were calculated with NONA and WinClada using 1000 replications, 10 search reps, 1 starting tree per rep, “don’t do max*(TBR)”, and save the consensus of each replication. The resulting fully resolved cladogram from the parsimony analysis is shown below.

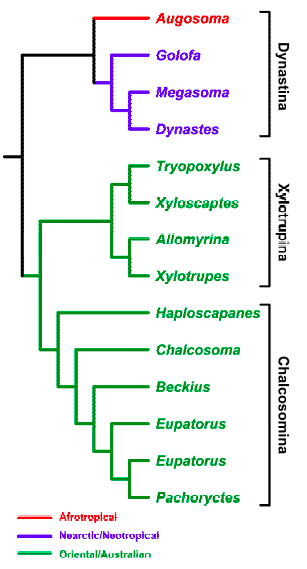

On the left is the single most parsimonious cladogram resulting from analysis of morphological and molecular data, while a summary tree is shown on the right.

Numbers immediately above hashmarks are morphological character numbers. Numbers below hashmarks are character state numbers derived on that branch. Numbers in bold above branches are bootstrap support values. Inset branching diagram is single most parsimonious cladogram from analysis of all data with branch lengths proportionate to number of character state transformations mapped using “fast” optimization. From Rowland and Miller, pending permission from the authors.

The trees show that the genus Xylotrupes is sister to Allomyrina, a genus of japanese rhinoceros beetles. This group, is in turn sister to a group containing Trypoxylus (also a japanese rhinoceros beetle) and Xyloscaptes. This is an interesting result, as in terms of horn morphology, Xylotrupes is more similar to Xyloscaptes while Allomyrina and Trypoxylus// look almost identical, but the groupings show a relationship differing from expectations. In any case, the four genera are well-supported as monophyletic, with Rowland and Miller proposing recognition of Xylotrupina as a valid subtribe.

References

- ^ Eberhard, W. G. (1977). Fighting behavior of male Golofa porteri beetles (Scarabeidae: Dynastinae). Psyche 83(3-4):292-298.

- ^ Eberhard, W. G. (1979). The function of horns in Podischnus agenor (Dynastinae) and other beetles. Pages 231-258 in M. Blum and N. Blum, eds. Sexual selection and reproductive competition in insects. Academic Press, New York.

- ^ Eberhard, W. G. (1980). Horned beetles. Sci. Am. 242(3):166-182.

- ^ Eberhard, W. G. (1982). Beetle horn dimorphism: making the best of a bad lot. The American Naturalist, 119(3), 420-426.

- ^ Matthews, P. (1992). The Guinness Book of World Records. Enfield, UK: Guinness Publishing Ltd.

- ^ Kram, R. (1996). Inexpensive load carrying by rhinoceros beetles. Journal of Experimental Biology, 199(3), 609-612.

- ^ Emlen, D. J. (1997). Alternative reproductive tactics and male-dimorphism in the horned beetle Onthophagus acuminatus (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae). Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 41(5), 335-341.

- ^ Bristowe, W. S. (1932). Insects and other invertebrates for human consumption in Siam. Transactions of the Royal Entomological Society of London, 80(2), 387-404.

- ^ Gillott, C. (2005). The Remaining Endopterygote Orders. Entomology, 297-351.

- ^ Truman, J. W., & Riddiford, L. M. (1999). The origins of insect metamorphosis. Nature, 401(6752), 447-452.

- ^ Leefmans, S. (1931). Xylotrupes gideon. TVdschr. Ent. 64: 11-13.

- ^ Kalshoven, L. G. E. (1951). The Pests of Cultivated Plants in Indonesia. Part II. De plagen van de eultaurgewassen in Indonesië. Deel II., 513-1065.

- ^ Bedford, G. O. (1980). Biology, ecology, and control of palm rhinoceros beetles. Annual Review of Entomology, 25(1), 309-339.

- ^ Firake, D. M., Deshmukh, N. A., Behere, G. T., Thakur, N. A., Ngachan, S. V., & Rowland, J. M. (2013). First report of elephant beetles in the genus Xylotrupes Hope (Coleóptera: Scarabaeidae) attacking guava. The Coleopterists Bulletin, 67(4), 608-610.

- ^ Endrodi, S. (1985). The Dynastinae of the world. Dr. W. Junk.

- ^ Zunino, M. (2014). About dung beetles (Coleoptera: Scarabaeoidea) genitalia: Some remarks to a recent paper. Acta Zoológica Mexicana (nueva serie), 30(2), 439-443.

- ^ Wongdao, S., & Black, R. (1987). Xylotrupes gideon eating bark of apple and pear trees in Northern Thailand.

- ^ Bedford, G. O. (1980). Biology, ecology, and control of palm rhinoceros beetles. Annual Review of Entomology, 25(1), 309-339.

- ^ Bedford, G. O. (1975). Observations on the biology of Xylotrupes gideon (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae: Dynastinae) in Melanesia. Australian Journal of Entomology, 14(3), 213-216.

- ^ Rowland, J. M. (2003). Male horn dimorphism, phylogeny and systematics of rhinoceros beetles of the genus Xylotrupes (Scarabaeidae: Coleoptera). Australian Journal of Zoology, 51(3), 213-258.

- ^ Allsopp, P. G. (1991). Morphological variation in adult Xylotrupes gideon australicus (Scarabaeidae, Coleoptera, Insecta). Journal of Morphology, 207(1), 53-58.

- ^ //

Rowland, J. M., & Miller, K. B. (2012). Phylogeny and systematics of the giant rhinoceros Beetles (Scarabaeidae: Dynastini). - ^ Goloboff, P. (1995). NONA. Published by the author; Tucumán, Argentina.

- ^ Nixon, K. C. (2002). WinClada ver. 1.0000 Published by the author, Ithaca, NY, USA.