Mata putih (Bahasa Melayu)

|

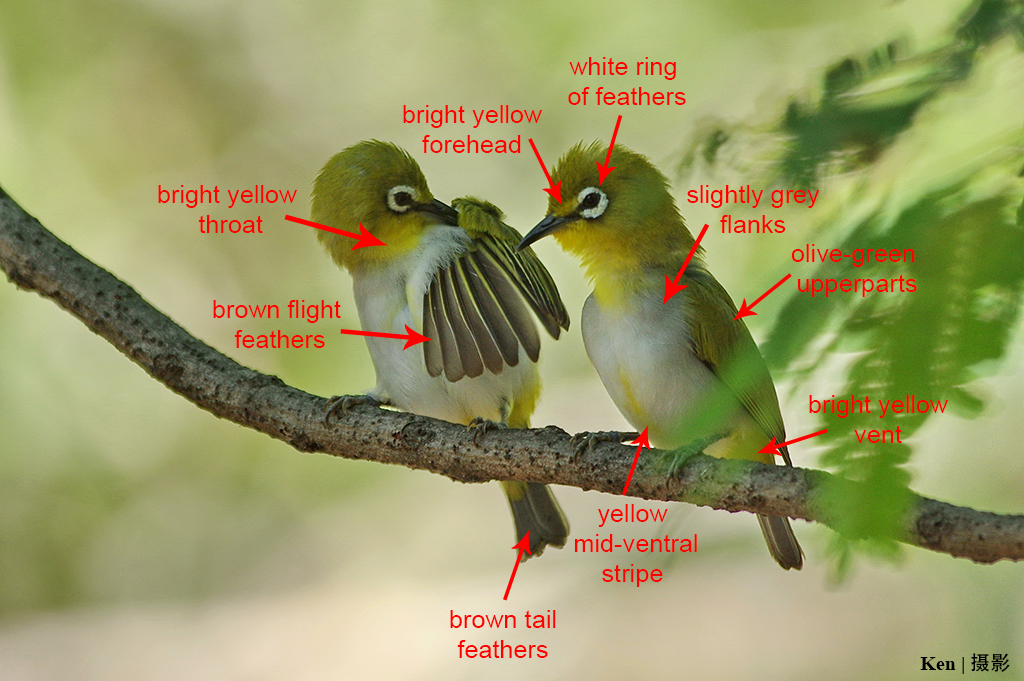

| Figure 1: A pair of adult Oriental White-eyes perched on a branch. (Photograph by © Ken Goh, 2012, permission pending) |

Table of Contents

Introduction

The Oriental White-eye (Zosterops palpebrosus) is a small passerine (aka songbird) that has a characteristic white ring of feathers around its eyes. This residential species occurs in a wide range of habitat, from forests, mangroves to urban parks and gardens[1] . It is also well-known for its melodious song, thereby making it highly sought after by the caged bird trade. In Singapore herself, the high levels of poaching in the 1970s played a role in a local extinction event[2] . However, the population of Oriental White-eyes rebounded to healthy levels but is suspected to be made up of both native and non-native individuals that were escaped or released from the cage bird trade.This page aims to provide you with a complete set of knowledge regarding the biology of the Oriental White-eye and the threats this species face today. Read on and share!

Name Explained

The scientific name of this species is Zosterops palpebrosus. The generic epithet Zosterops is a New Latin word derived from Greek which means girdle-eye. The species epithet palpebrosus is derived from the Latin word palpebra which represents eyelids.The common name, the Oriental White-eye, is derived from the bird's range in the Asiatic Old World (Oriental) and its prominent white ring of feathers around its eye (White-eye). The Old World region represents the land mass that includes Europe, Africa and Asia.

Description

Description based on A Field Guide to Birds of South-East Asia by Craig Robson (2008)[3] .The Oriental White-eye is a small sized bird growing up to 11 centimetres. This species is monomorphic (both sexes look alike).

|

| Figure 2: A pair of adult Oriental White-eyes perched on a branch. (Photograph by © Ken Goh, 2014, permission pending) |

| Description |

|

| Head |

|

| Body |

|

| Wing |

|

| Tail |

|

| Leg |

|

Young chicks lack the white eye-ring before growing them some time after they fledged. Similar to most passerines, the young chicks and juveniles possess a fleshy gap, a characteristic juvenile trait.

|

| Figure 3: A juvenile Oriental White-eye (Photograph by © Chong Lip Mun, 2013, permission granted). Annotations by Bryan Lim. |

Other Confusing Species

The Oriental White-eye can be commonly mistaken for the Everett's White-eye (Zosterops everetti) and the Japanese White-eye (Zosterops japonicus). The white-eye taxa is highly cryptic with almost similar morphology. Here we will look at a summarised table of these three taxa which occur in Singapore simultaneously. Use this table as a guide if you see one of the white-eyes in the wild. The Japanese white-eye is not a native species but instead feral ones from the songbird trade[4] . These are either escapees or released individuals. Amongst the three species described below, the Oriental White-eye is famed for having the best singing capibilities.| Oriental White-eye (Zosterops palpebrosus) |

Everett’s White-eye (Zosterops everetti) |

Japanese White-eye (Zosterops japonicus) |

|

| Size (cm) |

10.5 – 11 |

11 – 11.5 |

10 – 11.5 |

| Forehead |

Yellow |

Yellow |

Olive-green |

| Upper-parts |

Yellow-green |

Yellow-green |

Olive green |

| Ventral stripe |

Present, Yellow |

Present, Thicker yellow |

Absent |

| Flanks |

Slightly grey |

Deep grey |

Deep grey |

Distribution Range

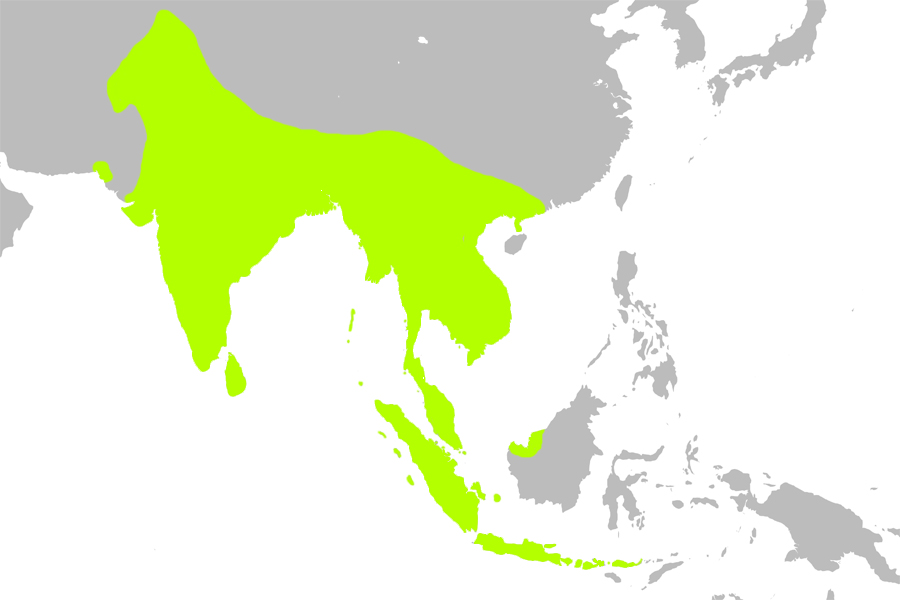

The Oriental White-eye has a wide Asiatic Range, extending from the Indian subcontinent including Sri Lanka, to Borneo and the lesser Sunda Islands (Nusa Tenggara)[5] [6] . Across these countries, there are a total of 11 subspecies[7] with variation in plumage morphology (including a full yellow-bellied morph)[8] [refer to section on Taxonomy and Systematics]. However, recent molecular studies on the white-eye taxa shows possible multiple species within the Oriental White-eye species complex[9] [refer to section on Phylogeny].

|

| Figure 4: Distribution of the Oriental White-eye. Annotated by Bryan Lim. |

Habitat

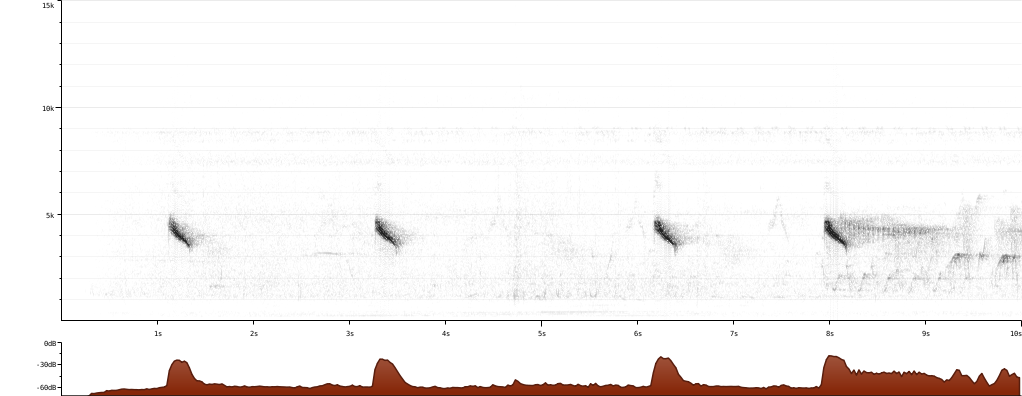

The Oriental White-eye resides in a wide spectrum of habitats that includes primary forests, secondary forests, forest edges, mangroves, urban parks and gardens[10] . This species usually stays high up in the canopy of vegetation in the above-mentioned habitats. As they camouflage well in the trees, spotting them can be quite tricky. It would be easier if you hear their unique song and calls first, and then look around for them [refer to Vocalisation section for more information].Vocalisation

This bird is famously known for its vocalisations, hence its popularity in the cage bird trade. Similar to most Passerines, the Oriental White-eye has two type of vocalisations - the song and the call[11] . Songs are mainly used for territorial ownership and attracting mates while calls are usually for alarm or signalling.The main sound the white-eye makes is a single 'cheuw', made in varying tunes and intervals[12] .

Here's a short video showcasing the excellent singing capability of the Oriental White-eye. This continuous burst of 'cheuws' are known in song bird competitions as 'buka' (open in Bahasa Melayu). This means that the white-eye has already reached maturity, with an 'opened' voice, signalling its readiness for competitions.

|

| Figure 5: Sonogram from http://www.xenocanto.com of the Oriental White-eye's call |

In the cage bird trade, male Oriental White-eyes are the more popular sex as they are better singers than their female counterparts. In cage bird competitions, male Oriental White-eyes are pitted against one another to determine the best singer. Through territorial ownership aggression, the stronger male will sing louder and longer, hence causing the other white-eyes to 'lose out' in the competition. The strongest male at the end of the competition will be crowned the champion.

Below is a short video clip of a Oriental White-eye singing competition in Serangoon, Singapore.

As mentioned in the Introduction, the Oriental White-eye's exceptional singing ability makes it a hot target for poachers. The trapping of Oriental White-eyes is extremely unsustainable and this has already led to a local extinction event in the 1970s. Instead of keeping the bird in cages, let this species be free into the wild and enjoy their beautiful songs in a natural environment [refer to Local Threats for more information].

Local Threats

The biggest threat this species face in Singapore today is poaching. Using a decoy bird, trained by a poacher to attract the highly social white-eyes, a three-chambered cage (including two spring traps) is set up high into the canopy layer. Together with a fruit bait, the decoy bird will start singing to lure the victims in. Once a white-eye perches on the spring trap, the cage will snap shut.Refer to this video to see how the poaching process works.

Because of heavy poaching activities in the 1970s, the local population of Oriental White-eye was declared Extinct in the Singapore Red Data Book[13] . However, after the extirpation event, the Oriental White-eyes population started increasing again steadily. Local populations now are made up of ferals and escapees, including other white-eye taxa like the Japanese White-eye (Zosterops japonicus)[14] . In the second edition of the Singapore Red Data Book (2008), the Oriental White-eye taxon was no longer listed, indicative of a healthy population size and little threats[15] .

Poaching of wildlife is a serious offence that is punishable by law. Despite so, there is still a slight degree of poaching still prevailing, even in the local nature reserves. The penalties of poaching in Singapore includes,

- A maximum of $1,000 fine for killing, taking, or keeping any wild animal or bird without a licence. (Under the Wild Animals and Birds Act - Chapter 351)

- A maximum fine of up to $50,000 or jail up to 6 months, or both, for capturing, collecting or removing any animal from the national parks and nature reserves. (Under the Parks and Trees Act - Chapter 216)

Asian Songbird Trade Crisis Summit

The Asia Songbird Trade Crisis Summit in 2015 has already identified the Oriental White-eye, Zosterops palpebrosus, as one of the key species in need of urgent conservation attention[16] . This summit was held by Wildlife Reserve Singapore (WRS), TRAFFIC and Cikananga Wildlife Center. The Zosterops palpebrosus species complex is incredibly cryptic, resulting in a taxonomic mess of the species [refer to section on Phylogeny]. There is an urgent need to provide phylogenetic resolution to the species to prevent more undetected extinctions in the years to come.Global Threats

In Malaysia and Indonesia, the Oriental White-eye is one of the more popular hobby bird and thus is constantly poached in its natural habitat, fueling its decline in their wild population.| Figure 6: An overcrowded cage of Oriental White-eyes left in unsanitary conditions in Kedah, Malaysia. Photograph by © Bryan Lim, 2016 |

In Indonesia, the species is threatened by the same songbird competition pressure and the threat is further fueled by a traditional, centuries-old Javan cultural practice.

A sister species to the Oriental White-eye, the Javan white-eye (Zosterops flavus) is heavily threatened by Indonesia's cage bird trade almost to a point of extinction[17] . Being one of the most affordable bird in Java, if the Javan white-eye were to go extinct by trade, it could be potentially possible that the subspecies in Java, Zosterops palpebrosus melanurus and Zosterops palpebrosus buxtoni, would be targeted next, driving population size down even further.

Diet and Feeding Habits

The Oriental White-eye is an omnivore that feeds on both small insects and fruits. For young chicks still in nest, they are fed with mainly insects. This supplements a diet with a higher protein content for growth and development.Social Organisation

The Oriental White-eye is a highly social species, often found in either pairs or flocks when foraging. Being very social birds, poaching of them is relatively easy using a decoy bird trained by a poacher. [refer to Global Threats for more information] |

| Figure 7: A flock of Oriental White-eye foraging together in a stream in Gujarat, India. (Photograph by © Viral Patel & Pankaj Maheria, 2015, permission granted) |

Reproduction

During nesting, the parental Oriental White-eye builds a small cup-shaped nest along a few branches, made of small twigs. The maternal white-eye lays a total of 2-3 eggs[18] at one breeding season, incubating up to weeks before the eggs hatch. Eggs are small and off-white in colour.| Figure 8: Oriental White-eye and its nest. (Photograph by © Nandita Amin, 2010, permission pending) |

|

| Figure 9: A nest of three eggs. (Photograph by © KS Bains, 2013, permission pending) |

|

| Figure 10: A photo montage of an adult Oriental White-eye feeding its chicks. (Photograph by © Chan Yoke Meng, 2007, permission pending) |

|

| Figure 11: An adult Oriental White-eye (yellow-bellied morph) feeding its fledged chicks. (Photograph by unknown) |

IUCN status and Conservation

The Oriental White-eye is listed in the IUCN Red List as Least Concern[20] . It is because of its large range, from the Indian subcontinent beginning at Pakistan, extending east-wards up to the Lesser Sundas [refer to section on Distribution Range], and its large global population size that does not hit Vulnerable threshold according to IUCN's range size criterion. However, the global population size is noted to be decreasing but not rapid enough to reach Vulnerable threshold as well.Red list assessments in the past shows the Oriental White-eye's conservation status to be listed as Least Concern in 2004, 2008 and 2009. Before 2004, the species was listed as Lower Risk/Least Concern in 1988, 1994 and 2000[21] .

In Singapore, the problem of escaped non-native white-eyes species can have ecological conservation implications. These non-native individuals can result in the following consequences:

* Competition for food in natural areas

* Interbreeding with native Oriental white-eyes

* Overall confusion for what we currently have in Singapore

* What are we conserving now? Are we protecting our natural heritage?

Taxonomy and Systematics

A hierarchical summary of the Oriental White-eye, Zosterops palpebrosus, is as stated below.Animalia

- Chordata

-- Aves

--- Passeriformes

---- Zosteropidae (Bonaparte, 1853)

----- Zosterops (Vigors & Horsefield, 1827)

------ Zosterops palpebrosus (Temminck, 1824) (revised)

Synonyms

Sylvia palpebrosus

Subspecies

There are currently 11 subspecies recognised with the native subspecies in Singapore to be //Z. p. auriventer[22] .

Subspecies represents members of the same species being able to interbreed with one another and produce fertile offspring but they are unable naturally due to geographical separation and sexual selection, they are taxonomically different from other populations of that species (Mayr, 1982). In the table below, we look at the various subspecies of the Oriental White-eye and their respective range.

| Subspecies name |

Authority |

Distribution |

| Z. p. palpebrosus |

Temminck, 1824 |

Arabia, Afghanistan, Pakistan, NE India – S China, Myanmmar |

| Z. p. nilgiriensis |

Ticehurst, 1927 |

Western Ghats, SW India |

| Z. p. salimalii |

Whistler, 1933 |

Eastern Ghats, SE India |

| Z. p. egregius |

Madarasz, 1911 |

Lowlands in India, Laccadive Island, Sri Lanka |

| Z. p. siamensis |

Blyth, 1867 |

South Myanmar, NE & SE Thailand, NW Indochina |

| Z. p. nicobaricus |

Blyth, 1845 |

Andaman Island, Nicobar Island |

| Z. p. williamsoni |

Robinson & Kloss, 1919 |

Gulf of Thailand (coastal), W Cambodia |

| Z. p. auriventer |

Hume, 1878 |

W Coast Thailand, Peninsular Malaysia, Singapore, E Coast Sumatra, Riau Islands, Borneo |

| Z. p. buxtoni |

Nicholson, 1879 |

Highlands of Sumatra, extreme W Java |

| Z. p. melanurus |

Hartlaub, 1865 |

Java, Bali |

| Z. p. unicus |

E. J. O. Hartert, 1897 |

Lesser Sundas |

|

| Figure 12: A yellow-bellied morph Oriental White-eye at Chiang Mai, Thailand. Photograph by © Ayuwat Jearwattanakanok, 2014, permission granted |

Phylogeny

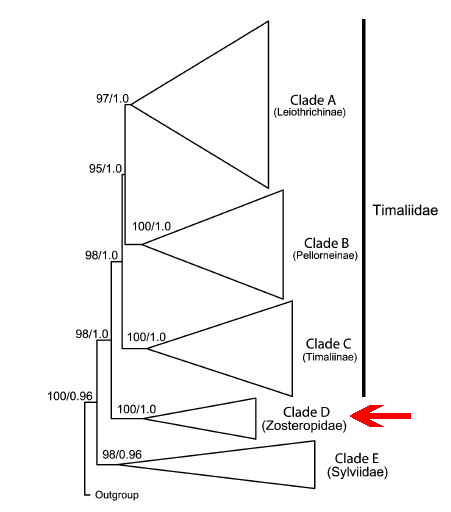

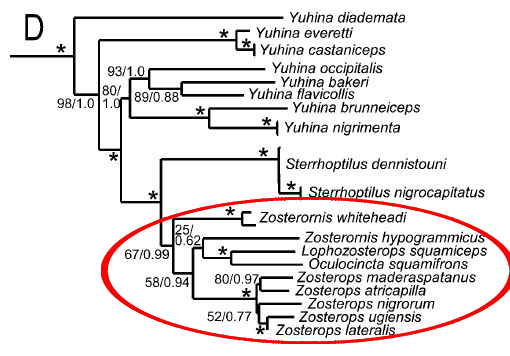

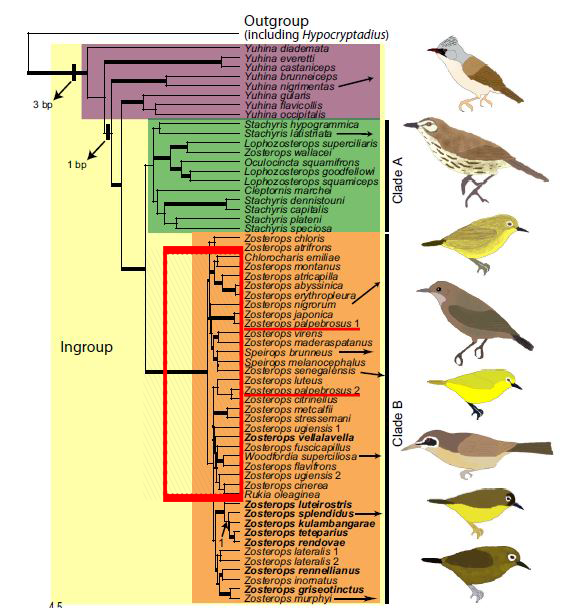

The Oriental White-eye is nested in the clade Passeri of the Passeriformes[24] . They are part of the Oscines group, more commonly known as Songbirds. The Oscines are the most recent divergence in the Aves evolutionary tree, radiating from Australia and New Zealand to the rest of the world[25] .Within the Oscines, the white-eye family was historically associated with the babblers and the laughingthrushes forming the Timaliidae family[26] . The Timaliidae was also known for its 'dumping ground' genera for genera that did not fit well in other families.With the advancement of molecular tools, phylogenetic resolution can be applied to this scrap basket genera, resolving the taxonomic mess of this clade. We see the Zosteropidae family being sister groups at (98 bootstrap value) to the rest of the Timaliidae - Old World Babblers (Timaliinae), Ground Babblers (Pellorneinae) and the Laughingthrushes (Leiothrichinae)[27] . Nested within the Zosteropidae family, we see the White-eyes and the Yuhinas[28] (Figure 13 and 14). This phylogenetic tree was constructed using a wide array of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) - Cytochrome b, ND2, ND3, TGFB2, Fib5 and MUSK. Using Maximum Likelihood analysis and Bayesian Posterior Probability (left and right respectively on the tree), we can see a very strong support for the phylogenetic tree where we can conclude that the family Zosteropidae is the sister family to the rest of the Timaliidae babblers and laughingthrushes.

|

| Figure 13: Phylogeny of Zosteropidae (Moyle et al., 2012) |

|

| Figure 14: Members of the Zosteropidae Family (Moyle et al., 2012) |

However, recent molecular data revealed surprising results. Mitochondrial DNA showed the two subspecies that are furthest apart geographically - Zosterops palpebrosus palpebrosus (from India) and Zosterops palpebrosus unicus (Flores Island, Nusa Tenggara) are not in the same clade/group and actually not closely related[33] . Mitochondrial ND2, ND3 and TGFB2 genes of many Zosterops species were sequenced and placed together on a phylogenetic tree. Using Maximum Likelihood and Bayesian Posterior Probabilty (thickened branch: >0.95 posterior probabilty and >70 bootstrap support), we see the Indian Oriental White-eye (Zosterops palpebrosus 1) being closely related to the Japanese White-eye (Zosterops japonicus) and the Nusa Tenggara Oriental White-eye (Zosterops palpebrosus 2) being closely related to the rest of the Indonesian white-eyes of different species (Figure 15).

|

| Figure 15. A phylogenetic tree of various species of Zosterops (Moyle et al., 2009). Annotated by Bryan Lim. |

Using the Phylogenetic Species Concept sensu Mishler and Theriot, there is no monophyly within the Zosterops palpebrosus species. Hence, we are currently unable to delimit Zosterops palpebrosus as a species. This poses a problem for the other Oriental White-eyes between the two geographic extremes. The Oriental White-eye now describes different taxa that are not related and forms a species complex that is entirely unknown and largely confusing. More phylogenetic and molecular work can be done on this species complex to provide resolution on the other potential errors that taxonomists might have had morphologically.

Potential Conservation Status

With the looming extinction threats facing the Oriental White-eyes in Indonesia and Malaysia by the song bird trade, phylogenetic resolution on the Zosterops palpebrosus species complex has to be done quickly in other to find the taxa which are genetically distinct from the rest. From there, we are able to elevate these taxa to species level (if deserving) and thus be able to direct conservation money to these threatened birds. If not, this 'newly elevated' species might go extinct undetected from the booming traded song bird industry.Online Resources

Genbank has barcode sequences of the Oriental White-eye, Zosterops palpebrosus, for several genes. They include the TRM2 gene, ND2 gene, ND3 gene, TGFB2 gene, cytochrome b gene.The full genome of the Oriental White-eye is yet to be sequenced, and the closest reference genome for the species will be the silvereye, Zosterops lateralis[34] .

- ^ Robson, C. (2008). A Field Guide to the Birds of southeast Asia. Á New Holland Publishers.

- ^ Ng, P. K., Wee, Y. C., & Breweries, A. P. (1994). The Singapore red data book: Threatened plants and animals of Singapore. Nature Society.

- ^ Robson, C. (2008). A Field Guide to the Birds of southeast Asia. Á New Holland Publishers.

- ^ Chisholm, R. A., Giam, X., Sadanandan, K. R., Fung, T., Rheindt, F. E. (2016). A robust nonparametric method for quantifying undetected extinctions. Conservation Biology, in press.

- ^ van Balen, B. (2016). Oriental White-eye (Zosterops palpebrosus). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. (retrieved from http://www.hbw.com/node/60163 on 8 November 2016).

- ^ BirdLife International. (2012). Zosterops palpebrosus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2012: e.T22714030A39625272. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2012-1.RLTS.T22714030A39625272.en. Downloaded on 08 November 2016.

- ^ van Balen, B. (2016). Oriental White-eye (Zosterops palpebrosus). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. (retrieved from http://www.hbw.com/node/60163 on 8 November 2016).

- ^ Robson, C. (2008). A Field Guide to the Birds of southeast Asia. Á New Holland Publishers.

- ^ Moyle, R. G., Filardi, C. E., Smith, C. E., & Diamond, J. (2009). Explosive Pleistocene diversification and hemispheric expansion of a “great speciator”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(6), 1863-1868.

- ^ Robson, C. (2008). A Field Guide to the Birds of southeast Asia. Á New Holland Publishers.

- ^ Catchpole, C. K., & Slater, P. J. (2003). Bird song: biological themes and variations. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Robson, C. (2008). A Field Guide to the Birds of southeast Asia. Á New Holland Publishers.

- ^

Ng, P. K., Wee, Y. C., & Breweries, A. P. (1994). The Singapore red data book: Threatened plants and animals of Singapore. Nature Society.

Eaton, J A, Shepherd, C R, Rheindt, F E, Harris, J B C, van Balen, S B, Wilcove, D S, and Collar, N J. 2015. Trade-driven extinctions and near-extinctions of avian taxa in Sundaic Indonesia. Forktail 31: 1-12.

Doyle, E. E. (1933). "Nesting of the White-eye (Zosterops palpebrosa Temm.)". J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 36 (2): 504–505.

Doyle, E. E. (1933). "Nesting of the White-eye (Zosterops palpebrosa Temm.)". J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 36 (2): 504–505.

BirdLife International. (2012). Zosterops palpebrosus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2012: e.T22714030A39625272. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2012-1.RLTS.T22714030A39625272.en. Downloaded on 08 November 2016.

BirdLife International. (2012). Zosterops palpebrosus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2012: e.T22714030A39625272. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2012-1.RLTS.T22714030A39625272.en. Downloaded on 08 November 2016.

van Balen, B. (2016). Oriental White-eye (Zosterops palpebrosus). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive//. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. (retrieved from http://www.hbw.com/node/60163 on 8 November 2016).

Robson, C. (2008). A Field Guide to the Birds of southeast Asia. Á New Holland Publishers.

Diamond, J. M., Gilpin, M. E., & Mayr, E. (1976). Species-distance relation for birds of the Solomon Archipelago, and the paradox of the great speciators. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 73(6), 2160-2164.

Moyle, R. G., Filardi, C. E., Smith, C. E., & Diamond, J. (2009). Explosive Pleistocene diversification and hemispheric expansion of a “great speciator”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(6), 1863-1868.

Cornetti, L., Valente, L. M., Dunning, L. T., Quan, X., Black, R. A., Hébert, O., & Savolainen, V. (2015). The genome of the “great speciator” provides insights into bird diversification. Genome biology and evolution, 7//(9), 2680-2691.