Table of Contents

Tawny Coster

1 Introduction

The Tawny Coster, Acraea terpsicore belongs to the largest family of butterflies Nymphalidae [1] . Butterflies of family Nymphalidae are commonly known as four-footed butterflies as most species are known to stand on four legs with the another pair curled up[2] . This species is introduced to Singapore [3] . In September 2006, tawny coster was first discovered in Singapore at an open wasteland in the north-eastern part of Singapore. Since then, it has spread to many other parts of Singapore and is now a commonly seen butterfly all over Singapore, including the offshore island of Pulau Ubin [4] . The rapid spreading Tawny Coster is suspected to be a potential invasive species. Please visit Section 1.1 The Journey of the Tawny Coster and Section 2.7 Conservation Status for more information regarding its spread and potential invasive status.

1.1 The Journey of the Tawny Coster

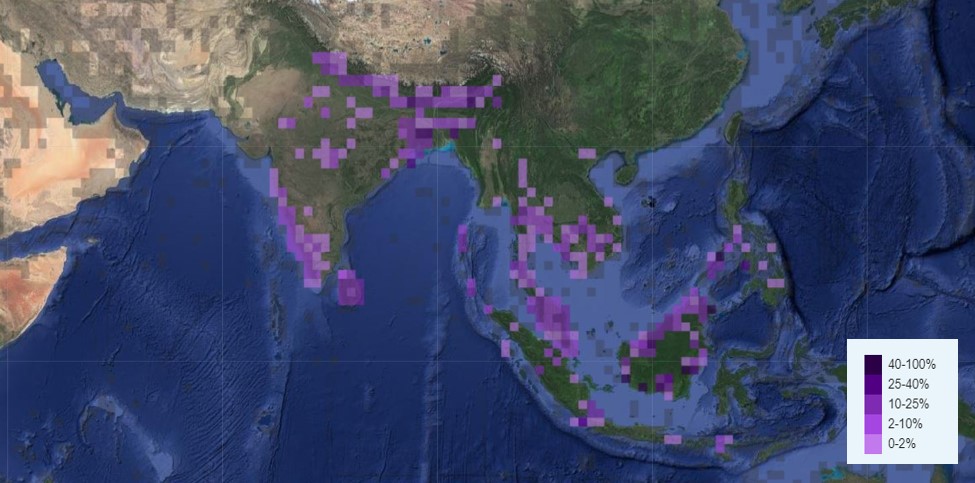

This species occurs naturally in grasslands and scrub jungles of peninsular India and Sri Lanka[5] . However, it has spread to South-East Asia during the past three decades. It has become widely established in the northern part of South-east Asia [6] . The first sighting of Tawny Coster was detected in Lombok Indonesia, Timor and Australia in 2012 [7] [8] . From the figure below, it can be observed that Tawny Coster has been travelling down South, from Sri Lanka and India to the further south South-East Asia and then Australia. Please visit Section 2.6 Global Distribution for its distribution worldwide.

While there have been competing hypotheses regarding the establishment of Tawny Coster in South-east Asia, Braby et al 2014 have postulated three hypotheses on its establishment[9] .

1. Tawny coster was accidentally and recently introduced to Indo-China from India/Sri Lanka

2. Tawny coster naturally expanded its range out of India and colonised Thailand via Myanmar

3. Tawny coster always existed in the region (Thailand and Vietnam), but has since become more abundant and widespread as a result of modification in the environment through agriculture, the butterfly favouring cultivated regions and degraded forests where the larval food plants grow.

A separate news article interviewing Dr Braby revealed a likely reason behind its establishment in South-East Asia. He revealed that tawny coster is not introduced by humans unlike many invasive species. Instead, it is speculated that human activity is the reason behind its rapid spread. Tawny coster breeds on plants that thrive in disturbed habitats[10] . With tropical forests in South-East Asia experiencing major deforestation, these host plants thrive [11] . Along with the chemical defense 'immunity' tawny coster has developed, these could have contributed to the range expansion of the tawny coster. Please visit Section 2.4 Defense for more information regarding its chemical defense.

1.1.1 Local Distribution

Local Distribution of tawny coster.

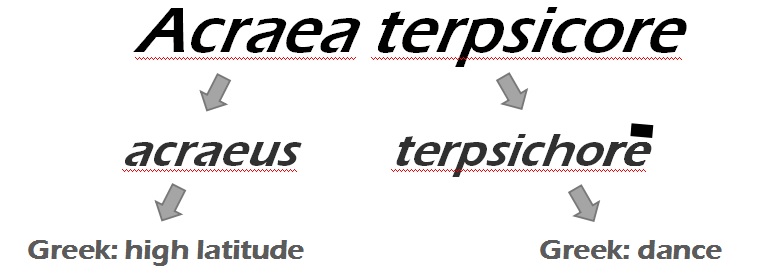

1.2 Etymology

The genus name Acraea is derived from the ancient Greek word acraeus which means at high latitude[12] . However, and strangely enough, tawny coster is in fact a lowland species[13] . The species name terpsicore is derived from the Greek word Terpsichorē, which refers to the Greek Muse of dancing and choral song, likely a reference to the lazy sailing dance-like fluttering of the tawny coster[14] . The common name Tawny refers to the tawny coloured wings of the tawny coster accompanied with black spots on them.

Dance-like fluttering of tawny coster. GIF adapted from Youtube video by Henrik Bloch.

2 Biology

Tawny coster is a medium-sized butterfly with the wingspan of an adult butterfly ranging from 48mm to 54mm [15] . The upperside is deep orange with narrow, black outer borders and black wing spots [16] . The black thorax and black hindwing border are spotted white. The underside is paler with markings more prominent.

2.1 Local Host Plants

The local caterpillar host plants are mainly from family Passifloraceae[17] . They include the following:| Scientific names |

Common names |

Family |

Local status |

Host plants for other butterflies found in Singapore |

| Passiflora foetida |

Stinking passionflower, love-in-a-mist |

Passifloraceae |

Non-native |

Cethosia cyane Leopard Lacewing (non-native) Dryas iulia Julia Heliconian (non-native) |

| Passiflora suberosa |

Corky-stemmed passion flower |

Passifloraceae |

Non-native |

Dryas iulia Julia Heliconian (non-native) |

| Passiflora edulis |

Passion fruit |

Passifloraceae |

Non-native |

|

| Turnera ulmifolia |

Yellow Alder |

Turneraceae |

Non-native |

Adults of tawny coster can usually be sighted visiting the flowers of stinking passionflower for the nectar while the caterpillars feed on the leaves, young shoots, tendrils and outer surface of the young stems.

Similar to the stinking passionflower, the other host plants are fast-growers that are able to smoother other plants, thus may also explain the spread of tawny coster across the island[22] .

2.2 Life Cycle

| Developmental stage |

Description [23] |

Photo by Horace Tan. Permission obtained. |

Oviposition (Depositing of eggs) Female tawny coster oviposits on the underside of stinking passionflower. |

Photo by Horace Tan. Permission obtained. |

Eggs The eggs are yellow in colour and olive-shaped. |

Photo by Horace Tan. Permission obtained. |

Mature eggs The infant caterpillar consumes the upper portion of the egg shell while hatching. |

Photo by Horace Tan. Permission obtained. |

1st instar The body segments develop a bright yellowish brown coloration. This instar lasts about 2 to 2.5 days. |

Photo by Horace Tan. Permission obtained. |

2nd instar Body turns orangy brown. This instar lasts 2 to 3 days. |

Photo by Horace Tan. Permission obtained. |

3rd instar Similar physical appearance as 2nd instar. This instar lasts 2 to 3 days. |

Photo by Horace Tan. Permission obtained. |

4th instar Similar physical appearance as 3rd instar, except for paler coloration in first two segments. This instar lasts 3 to 5 days. |

Photo by Horace Tan. Permission obtained. |

5th instar Little change to physical appearance except for the increase in size. This instar lasts 5 to 7 days. |

Photo by Horace Tan. Permission obtained. |

6th and final instar Head turning almost fully orange. This instar lasts between 9 to 13 days. |

Photo by Horace Tan. Permission obtained. |

Pupa Pupation takes place on the underside of the stem. White-based pupa has black narrow bands running lengthwise. This lasts for 5 days before the pupa matures and turns salmon orange. |

Photo by Horace Tan. Permission obtained. |

Eclosion Eclosion takes place one day after the pupa turns salmon orange. |

Tawny coster adult butterfly emerges from its pupal case. Original video from YouTube by Horace Tan

2.3 Sexual Dimorphism

Sexual dimorphism is the difference in morphology (physical appearance) between the male and female. It includes differences in size, coloration or body structures[24] .

The wings of the male are deep salmon orange (left) while the wings of the female are pale tawny yellow (right). Photo by paper from Braby et al. Permission pending.

2.4 Defense

2.4.1 Aposematism

Aposematism is a defense strategy adopted by species that warns potential predators of their unpalatability[25] . These species usually have conspicuous colour patterns, and potential predators will learn to associate these bright colouration to unpalatability of the species thus escaping predation. The predators thus learn from the experience and avoid any similar looking preys in the future.In the animal kingdom, the typical warning colours are black, yellow, red and orange [26] . Many butterflies that exhibit aposematic colouration come from the families Papilionidae and Pieridae, and subfamilies Danainae and Heliconiinae. Subfamily Heliconiinae, the subfamily which A. terpsicore belongs to, derive their unpalatability as caterpillars when they feed on Passifloraceae [27] . The caterpillars are able to sequester the toxins present in their Passifloraceae host plants which are then retained in the adult stage. The adults then secrete a foul smelling yellow oily fluid from their glands in leg joints when they are being attacked, making them unpalatable to the predators[28] . This mechanism thus protects butterflies from subfamily Heliconiinae from potential insectivorous predators such as birds.

2.4.2 Predators

Distasteful to predators, tawny coster is avoided by birds and most of the insects. Some mantises and lizards are noted to predate on the tawny coster.

2.5 Sphragis

In the animal kingdom, females are usually the higher investing sex and may have multiple mating partners[29] . Females are the higher parental investment mates as they support the weight of the many relatively heavy-weight eggs before fertilisation, and after fertilisation, dedicate to taking care of the offspring. Thus as the higher parental investment mates, the females can be choosy about their mates, as the quality of her offspring is dependent on the quality of her mate. This is commonly as known as female mate selection. One popular example is in frogs, where female frogs tend to be attracted to the males with the loudest and most distinctive acoustic display of their mating calls. Via the mating calls, the females would gain signals on the quality of the males, then select the male that would offer the highest in return for mating. In butterflies, female mate choice is dependent on both visual and olfactory cues[30] . Mate recognition is performed via visual cues, while olfactory scents are emitted by male butterflies to court the females in close range[31] .So... does it mean that the fate of the paternity solely depends on the female's choice? NO!!

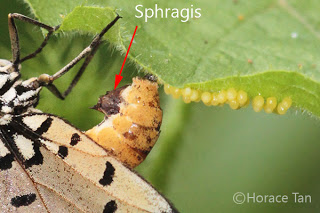

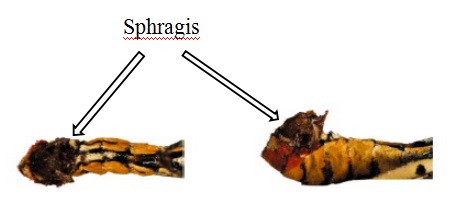

Sphragis on the female copulatory opening. Photo and annotation by Horace Tan. Permission obtained (left). Dorsal view of sphragis. Annotations by Sandy Tan. Photo from paper by Braby et al (middle) Permission pending. Lateral view of sphragis. Photo from paper by Braby et al (right). Permission pending.

With females being choosy with their mates, there exists high male-male competition as they compete for access to mating. Thus males have also evolved adaptations to increase males' chance of reproductive success [32] . Males can do so by post-copulatory sperm competition. One example of post-copulatory sperm compeition is the sphragis.

Male butterflies utilize a mechanical tactic known as the sphragis, mating plug or copulatory plug to reduce female re-mating tendencies to cope with sperm competition [33] . Sphragis is a glandular, waxy secretion which is passed along with the spermatophore (sperm packet). As female butterflies have two genital openings, the sphragis covers the female's copulatory opening without obstructing oviposition. This waxy secretion hardens within hours of copulation to prevent further mating of the females. The sphragis thus serves as a mechanical barrier to reinsemination of the female butterflies.

However, the effectiveness of sphragis in tawny coster is uncertain. In a study on the function of sphragis in the Chalcedon Checkerspot Butterfly Euphydryas chalcedona, belonging to Family Nymphalidae, it was discovered that sphragis does indeed prevent reinsemination [34] . The presence of sphragis did reduce the copulatory success of males courting the females by preventing intromission. In tawny coster, sphragis have been sighted on the mated females. However it remains unclear whether females do mate multiple times in the first place, or if the presence of sphragis do prevent reinsemination in tawny coster.

2.6 Global Distribution

Global Distribution of tawny coster. Blue markers indicate current distribution. Red markers indicate potential range expansion predicted by Braby et al 2014.

2.7 Conservation Status

Tawny coster has not yet been assessed for the IUCN Red List[35] . However, from its rapid spread, it seems unlikely that tawny coster would be facing any threat in the near future.The question better suited for tawny coster should be: Could tawny coster potentially be an invasive species since its host plant stinking passionflower is also spreading rapidly in Singapore?

The biological and economical impacts of tawny coster has yet to be studied, however, in Sri Lanka where this species is native in, tawny coster is infamous for being a pest for local market gardeners, destroying the harvest of various gourds of Family Cucurbitaceae[36] . Locally in Singapore, the relative abundance of P. foetida could be an explanation behind the rapid spread of tawny coster in Singapore. With an abundance of the host plant, the population of tawny coster is able to flourish as well.

A personal observation at Coney Island: There is an increase in spread of stinking passionflower (major host plant for tawny coster) in Coney Island to an extent that it seems to be growing at areas where Cynanchum ovalifolium Akar Bano was usually found to be present at. As a result, sightings of Danaus genutia genutia Common Tiger seemed to have lessened. Could it be that the spread of stinking passionflower could have indirectly resulted in the displacement of common tiger butterfly?

Common tiger (left). Photo by Sek Keung Lo from Flickr. Creative Commons. Akar bano (right) Photo by Horace Tan. Permission obtained.

3 Taxonomy and Systematics

3.1 Classification

Class: InsectaOrder: Lepidoptera

Superfamily: Papilionoidea

Family: Nymphalidae

Subfamily: Heliconiinae

Tribe: Acraeini

Genus: Acraea

There have been no subspecies listed under this species.

3.2 Original Linnaean Description

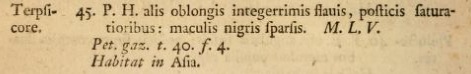

Original Linnaean description in Systema Naturae (1758).

Linnaeus described A. terpsicore as having oblong spotless yellow wings with its rear saturated with scattered black spots[37] .

3.3 Diagnosis

| Image |

Species |

Description |

Male tawny coster (bottom) and female tawny coster (top). Photo by Dallaprasad Sawant, permission pending. |

Acraea terpsicore Tawny Coster |

|

Female glasswing (left) and male glasswing (right). Photo by Michael Jefferies from Flickr. Creative Commons. |

Acraea andromacha Glasswing |

|

Photo by Katju Schulz from Flickr. Creative Commons. |

Danaus chrysippus chrysippus Plain Tiger |

|

Photo by Jonathan Leung from Flickr. Creative Commons. |

Danaus genutia genutia Common Tiger |

|

3.4 Nomenclature

Papilio terpsicore Linnaeus, 1758 is the oldest available name of this species [41] . The species was subsequently moved to a different genus Acraea and is named Acraea terpsicore (Linneaus, 1758).3.4.1 Synonyms

Papilio violae Fabricius, 1775Papilio cephea Cramer, 1780

Acraea violae (Fabricius, 1793)

There has been much confusion over the identity of this species as many authors pointed out that the Linnean type material used to describe this species has not been located[42] . It was then discovered that the type of tepsicore Linnaeus existed in the collections of the Linnean Society of London and identified as such[43] . The type of violae Fabricius is in the Zoological Museum, Copenhagen [44] .

As Papilio terpsicore Linnaeus, 1758 is the oldest available name, it is therefore a senior synonym of Papilio violae Fabricius, 1775.

Until now, there have been uncertainties regarding the scientific names of the Tawny Coster. Some online pages refer Tawny Coster to A. violae while others refer it as A. terpsicore.

Butterfly circle, a butterfly enthusiast group in Singapore have been using A. violae to describe Tawny Coster but since 2015, the scientific name of this species has been adopted as A. terpsicore.

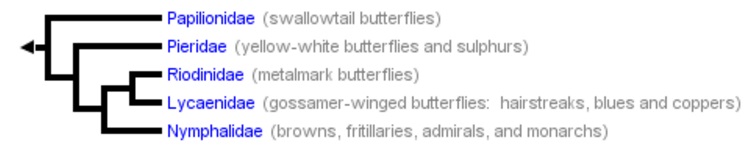

4 Phylogeny

The brush-footed butterflies (Nymphalidae) belongs to superfamily Papilionoidea. This superfamily consists of all the true butterflies of five families - Papilionidae, Pieridae, Nymphalidae, Riodinidae and Lycaenidae. An estimation of 13 700 species of true butterflies are extant in the world [47] .

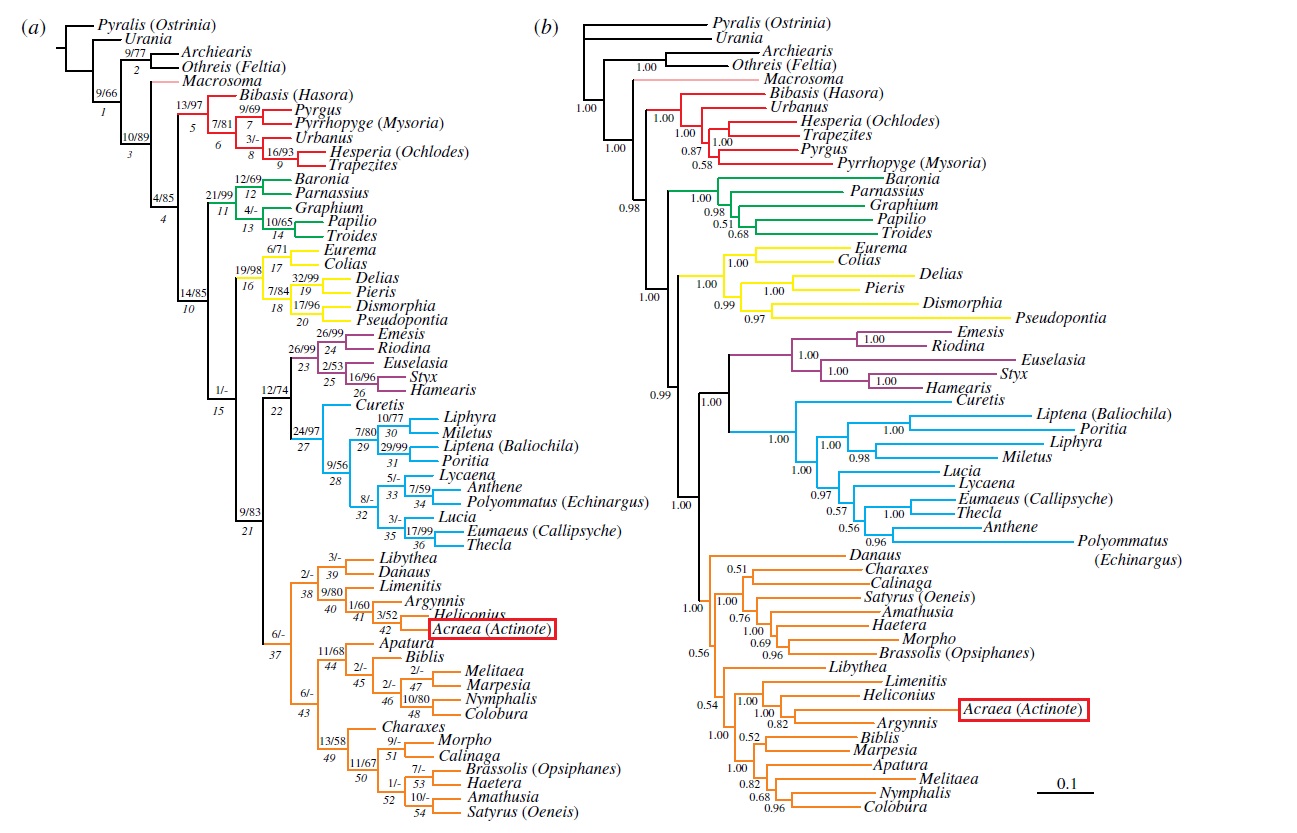

The subfamily Heliconiinae was recently divided into 4 tribes - Acraeini, Heliconiini, Vagrantini and Argynnini [48] . A. terpsicore belongs to the tribe Acraeini. Acraeini is thought to comprise between one and seven genera distributed in the Neotropics and Old World [49] .

Phylogenetic analyses were conducted based on both molecular and morphological data. The molecular sequence data were based on 2 nuclear gene region (EF-1a and Wingless) and 1 mitochondrial gene region (COI). The morphological data matrix involved a total of 99 characters, with 95 characters scored from adult butterflies, and 4 characters scored from immature stages[50] .

The analyses of the combined molecular and morphology dataset provide strong support for the monophyly of all traditionally recognised higher taxa. However Nymphalidae (family of the tawny coster) was an exception with moderate Bremer support (6), high posterior probability (100%) but no bootstrap support (less than 50%). Characters (morphology, COI and EF-1a) do support the monophyly of the family however Wingless conflicts moderately, which resulted in the above phylogenetic tree. A postulation regarding the unsupported monophyly of Nymphalidae is that the major lineages diverged very rapidly from one another. The uniquely derived features used to define the family is thus a challenge.

4.1 DNA Barcode

The DNA Barcode data for this species can be found here.- ^ Shields O (1989) World Numbers of Butterflies. Journal of the Lepidopterists’ Society, 43(3), 178-183.

- ^ "Brush-footed Butterflies (Family Nymphalidae)". iNaturalist, n.d.. URL:http://www.inaturalist.org/taxa/47922-Nymphalidae (Accessed on 12 Oct 2016)

- ^ Saji K, Gurjar Y, Kale P, Alaganantham TP, Jaikumar & Kunte K (2016) Acraea terpsicore Linnaeus, 1758 - Tawny Coster. Kunte K, Roy P, Kalesh S & Kodandaramaiah U (eds.) Butterflies of India, v. 2.24. Indian Foundation for Butterflies. URL: http://www.ifoundbutterflies.org/sp/573/Acraea-terpsicore

- ^ "Voyage of the Tawny Coster", Khew SK. Butterfly Circle, 06 Mar 2008. URL: http://butterflycircle.blogspot.sg/2008/03/voyage-of-tawny-coster.html (Accessed on 15 Oct 2016)

- ^ Braby MF, Bertelsmeier C, Sanderson C & Thistleton BM (2014) Spatial Distribution and range expansion of the Tawny Coster butterfly, Acraea terpsicore (Linnaeus, 1758) (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae), in South-East Asia and Australia. Insect Conservation and Diversity, 7, 132-143.

- ^ Braby MF, Bertelsmeier C, Sanderson C & Thistleton BM (2014) Spatial Distribution and range expansion of the Tawny Coster butterfly, Acraea terpsicore (Linnaeus, 1758) (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae), in South-East Asia and Australia. Insect Conservation and Diversity, 7, 132-143.

- ^ Matsumo K, Noerdjito WA & Cholik E (2012) Butterflies recently recorded from Lombok. Treubia, 39, 27-40.

- ^ Braby MF, Bertelsmeier C, Sanderson C & Thistleton BM (2014) Spatial Distribution and range expansion of the Tawny Coster butterfly, Acraea terpsicore (Linnaeus, 1758) (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae), in South-East Asia and Australia. Insect Conservation and Diversity, 7, 132-143.

- ^ Braby MF, Bertelsmeier C, Sanderson C & Thistleton BM (2014) Spatial Distribution and range expansion of the Tawny Coster butterfly, Acraea terpsicore (Linnaeus, 1758) (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae), in South-East Asia and Australia. Insect Conservation and Diversity, 7, 132-143.

- ^ "Indian butterfly crosses Asia and invades northern Australia", Ben C. ABC news, 16 Nov 15. URL: http://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-11-16/indian-butterfly-crosses-asia-and-invades-northern-australia/6916980 (Accessed on 22 Nov 2016)

- ^ "The forests of Southeast Asia". United Nations Environment Programme, n.d. URL: http://www.unep.org/vitalforest/Report/VFG-15-The-forests-of-southeast-asia.pdf (Accessed on 22 Nov 2016)

- ^

"acraeus (Latin)" WordSense.eu, n.d. URL: http://www.wordsense.eu/acraeus/ (Accessed on 21 Oct 2016)

"Terpsichore" Merriam webster, n.d. URL: http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/Terpsichore (Accessed on 18 Oct 2016)

Braby MF (2004) The Complete Field Guide to Butteflies of Australia.

Khew SK (2015) A Field Guide to the Butterflies of Singapore 2nd Edition.

"Life History of the Tawny Coster", Tan H. Butterfly Circle, 16 Feb 2013. URL: http://butterflycircle.blogspot.sg/2013/02/life-history-of-tawny-coster.html (Accessed on 17 Oct 2016)

"Weeds of Australia-Biosecurity Queensland Edition Fact Sheet". URL: http://keyserver.lucidcentral.org/weeds/data/media/Html/passiflora_foetida.pdf (Accessed on 18 Nov 2016)

"What is Sexual Dimorphism?", Klappenbach L. About, 04 Jun 2015. URL: http://animals.about.com/od/zoology12/f/sexualdimorphis.htm (Acessed on 19 Nov 2016)

Gideon VA, Rufus KC & Vivekraj P (2016) Record of New Larval Host Plant for Acraea terpiscore (Tawny coster). International Journal of Advances in Scientific Research, 2, 167-168.

Rojas B, Valkonen J & Nokelainen O (2015) Aposematism. Current Biology, 25(9), R350-R351.

Gideon VA, Rufus KC & Vivekraj P (2016) Record of New Larval Host Plant for Acraea terpiscore (Tawny coster). International Journal of Advances in Scientific Research, 2, 167-168.

Koskela E, Mappes T, Niskanen T & Rutkowska J (2009) Maternal Investment in Relation to Sex Ratio and Offspring Number in a Small Mammal - A Case for Trivers and Willard Theory? Journal of Animal Ecology, 78(5), 1007-1014.

Watanabe M (2016) Sperm Competition in Butterflies.

Leonard J & Cordoba-Aguilar A (2011) The Evolution of Primary Sexual Characters in Animals.

Dickinson JL & Rutowski RL (1989) The function of the mating plug in the chalcedon checkerspot butterfly. Animal Behaviour, 38, 154-162.

IUCN Red List. URL: http://www.iucnredlist.org/search (Accessed on 20 Oct 2016)

Braby MF, Bertelsmeier C, Sanderson C & Thistleton BM (2014) Spatial Distribution and range expansion of the Tawny Coster butterfly, Acraea terpsicore (Linnaeus, 1758) (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae), in South-East Asia and Australia. Insect Conservation and Diversity, 7, 132-143.

Linnaeus C (1760) Insecta Pelidoptera. Systema Naturae, Volume 1, Edition 10, Class 5, 466.

Honey MR & Scoble MJ (2001) Linnaeus's butterflies (Lepidoptera: Papilionidea and Hesperioidea). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 132, 277-399.

Saji K, Gurjar Y, Kale P, Alaganantham TP, Jaikumar & Kunte K (2016) Acraea terpsicore Linnaeus, 1758 - Tawny Coster. Kunte K, Roy P, Kalesh S & Kodandaramaiah U (eds.) Butterflies of India, v. 2.24. Indian Foundation for Butterflies. URL: http://www.ifoundbutterflies.org/sp/573/Acraea-violae

Honey MR & Scoble MJ (2001) Linnaeus's butterflies (Lepidoptera: Papilionidea and Hesperioidea). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 132, 277-399.

Robbins RK (1982) How many butterfly species? News of the Lepidopterist's Society.

"Nymphalidae" The Nymphalidae Systematics Group, n.d. URL:

http://www.nymphalidae.net/Nymphalidae.htm (Accessed on 08 Nov 2016)

Wahlberg N, Braby MF, Brower AVZ, Rienk de Jong, Lee M, Nylin S, Pierce NE, Sperling FAH, Vila R, Warren AD & Zakharov E (2005) Synergistic effects of combining morphological and molecular data in resolving the phylogeny of butterflies and skippers. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B, 272, 1577-1586.