Table of Contents

|

| Fig. 1. A pair of adult Javan mynas (Acridotheres javanicus). (Creative Commons License: CC BY-ND 2.0 DE) |

Introduction

The Javan myna is a conspicuous, vocal, and highly social bird that occurs in a wide range of relatively open habitat, thriving in rural as well as urban settings.(1) Native to Java and Bali, it has been widely introduced across Southeast Asia likely via the cage bird trade, and can now be found in many Southeast Asian countries, with an invasion front moving north up Peninsular Malaysia towards Thailand. Its adaptability and success at exploiting ephemeral food sources has led to its proliferation in urban cities such as Singapore, and to its current position as a significant pest species.(2)Etymology

The generic epithet Acridotheres is derived from the Greek words akrida, meaning a locust, and theres, a hunter, while the specific epithet javanicus is in reference to its native Java.(3)Identification

From Wells (2009) (1) and Feare & Craig (1999) (4) unless otherwise stated.General Identification

Adult Javan myna can be generally identified by the features given in Table 1. Distinctive characteristics for field identification are depicted in the two figures below as well. |

|

| Fig. 2. Adult Javan myna, front view. (Photo by Gabriel Low) |

Fig. 3. Adult Javan myna, rear view. (Photo by Gabriel Low) |

Table 1. General descriptive features of adult Javan mynas

| Body Part |

Description |

|

| Head (including lores, sides, cap, neck) |

|

|

| Central crown, nape |

|

|

| Upperparts (mantle, back and rump) |

|

|

| Underparts (chin, flanks and belly) |

|

|

| Primaries |

|

|

| Secondaries and tertials |

|

|

| Lesser- to secondary coverts |

|

|

| Primary coverts |

|

|

| Beak |

|

|

| Legs and feet |

|

|

| Iris |

|

|

| Tail |

|

|

Juvenile Javan mynas tend to be browner, with a very short brown frontal crest. Their underparts appear to be paler and mousier, sometimes with pale feather margins producing a streaky appearance. However, juveniles retain sharply white undertail-coverts very similar to adults. Likewise, the white bases to primaries and tail tip are present in juveniles, but in a narrower band.

Diagnosis

The Javan myna has been readily confused with several species of mynas. Leaving the question of conspecificity with certain other members of genus Acridotheres aside, the Javan myna (A. javanicus) has the following diagnostic characters that best set it apart from other myna species found existing in overlapping or adjacent ranges. |

Fig. 4. Javan myna (Acridotheres javanicus) (Creative Commons License: CC BY-SA 2.0)

|

|

Fig. 5. Common myna (A. tristis) (Public domain)

|

Fig. 6. Jungle myna (A. fuscus) (Photograph courtesy of Ronnie Ooi)

|

|

|

Fig. 7. Great myna (A. grandis) (Photograph by Marco Valentini, permission pending but within Fair Use)

|

|

Fig. 8. Pale-bellied myna (A. cinereus) (Photograph courtesy of Wong Tsu Shi)

|

Vocalizations

Like other Acridotheres mynas, the Javan Myna (A. javanicus) has a varied and strident voice.(1) It is capable of incorporating imitation into its song, and is now heard almost ubiquitously in urban centers within its range, such as Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia and Singapore. Vocalizations are used for many purposes including courtship and maintenance rituals, communication during foraging, and danger alarms.Listen to some sample song and call recordings hosted on xenocanto.org (5) using the embedded players below.

| Song |

Call |

Biology

Habitat

The species has been recorded in a wide range of inland man-modified, non-forest habitats, from palm plantations and open agriculture, to parkland, small settlements and suburbia, through to inner-city spaces including fully built-up city centers.(1)Social Behaviour

Javan mynas are social throughout the year and frequently occur in pairs, which are in turn nested within larger groups, especially when food is abundant or ephemeral.(1) Joining such parties may help individuals better make use of ephemeral food sources, such as would be common in an urban setting.(4)Javan mynas roost in large communal flocks in trees (Fig. 9), which can involve hundreds or even thousands of individuals.(1) Roosts are generally made in either clumps or discrete rows of tall (>10m), dense-crowned trees. As tree species selected for roadside planting tend to be large-crowned and shady, three species dominate as urban roost site favorites for the Javan Myna at least in Singapore: Pterocarpus indicus (Angsana), Terminalia catappa (Sea Almond), and Syzygium grande (Sea Apple), with Pterocarpus being most important.(6)

However, unlike the co-occuring Common Myna (A. tristis), Javan Mynas do not remain faithful to a single communal roost, but shift between up to 4 different ones, effectively maintaining an activity space on average three times larger than their co-occuring cousins.(7)

| Fig. 10. Javan myna perched on dustbin lid in an open air food centre. Javan mynas commonly exploit ephemeral food sources such as food clearing centres in such establishments. (Photo by Gabriel Low) |

Foraging Habits

The Javan myna is an omnivorous bird and is adept at exploiting a wide range of food sources. Their diet is primarily made up of invertebrates, although this is likely dependent on their locality—mynas in a highly urbanized environment may primarily exploit human refuse as a food source (Fig. 10). Javan mynas hunt arthropods and earthworms by probing bare ground or short grass with open bills, even taking Oecophylla weaver ants. They have also been observed aerial foraging for swarming ants and termites, attending oxen for disturbed invertebrate prey, and hunting small crabs on low-tide sand-flats. Javan mynas will take carrion (and the fly maggots found within), as well as fruit and nectar from both cultivated and wild species of plants. Examples include wild figs (Ficus spp.), papaya (Carica papaya), and banana (Musa sp.).(7) Aided by its flexible use of multiple communal roosting sites, Javan mynas are able to make much more efficient use of ephemeral food sources, contributing up to 16% of the intake in the Singapore population.Breeding Cycle

The Javan myna breeding cycle can be split into three phases: (1) courtship and pair bonding, (2) nesting and incubation, and (3) post-fledging care phases.(2) While breeding occurs throughout the year and does not start with the beginning of a calendar year, peaks in each of the three phases occur over the course of the year.Courtship and Pair Bonding

Javan myna courtship activities include fighting and fencing, as well as bowing courtship displays with vocalizations.(2) However, these activities are not entirely distinct from their usual maintenance behaviours and displays. This phase of the breeding cycle usually starts in August and peaks in December.

Nesting and Incubation

Javan mynas nest sites include palm fruit clusters amid palm crowns and holes in tall trees, buildings, bridges, and other manmade structures.(4) A clutch of 2–5 plain pale blue eggs are usually laid and incubated for 13–14 days. This phase of the breeding cycle usually starts by January and peaks in March.(2)

Post-fledging Care

Juvenile Javan mynas will follow their parents and beg to be fed.(2) This phase of the breeding cycle usually starts by April and peaks around June.

Range

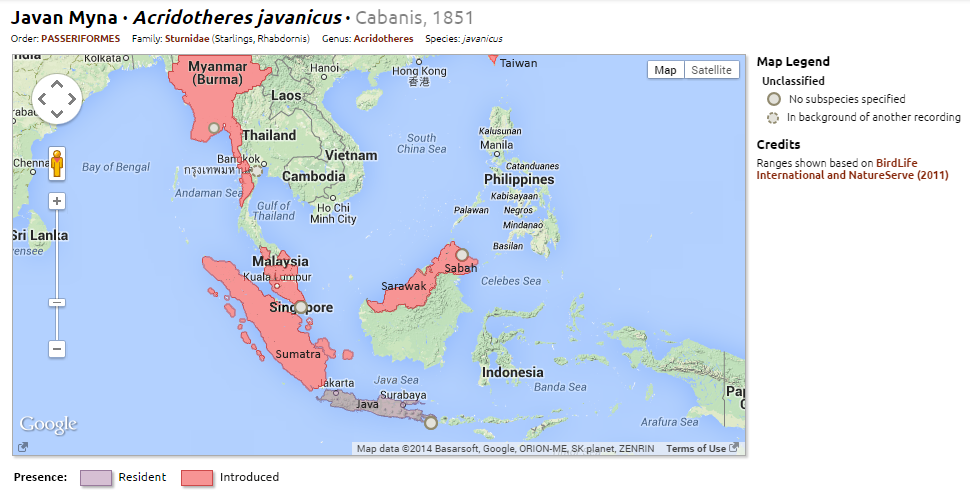

|

| Fig. 11. Distribution of the Javan myna (Acridotheres javanicus) across South-east Asia. Grey circles denote non-captive song recording locations (see section on Vocalizations). Range data originally sourced from BirdLife International and NatureServe (2011). (Adapted from xenocanto.org)(5) |

The Javan Myna’s range has not been assessed comprehensively, in part hampered by controversy regarding its taxonomy. However, it is generally agreed to be indigenous to Java and Bali, and subsequently introduced to Sarawak, Sumatra, Singapore, Peninsular Malaysia, the Lesser Sundas, and Myanmar within Southeast Asia (Fig. 11).(1)(4)(6) Elsewhere, it has also been introduced to Christmas Island, Taiwan, and Puerto Rico.(8)

Distribution and Movement in Singapore and Peninsular Malaysia

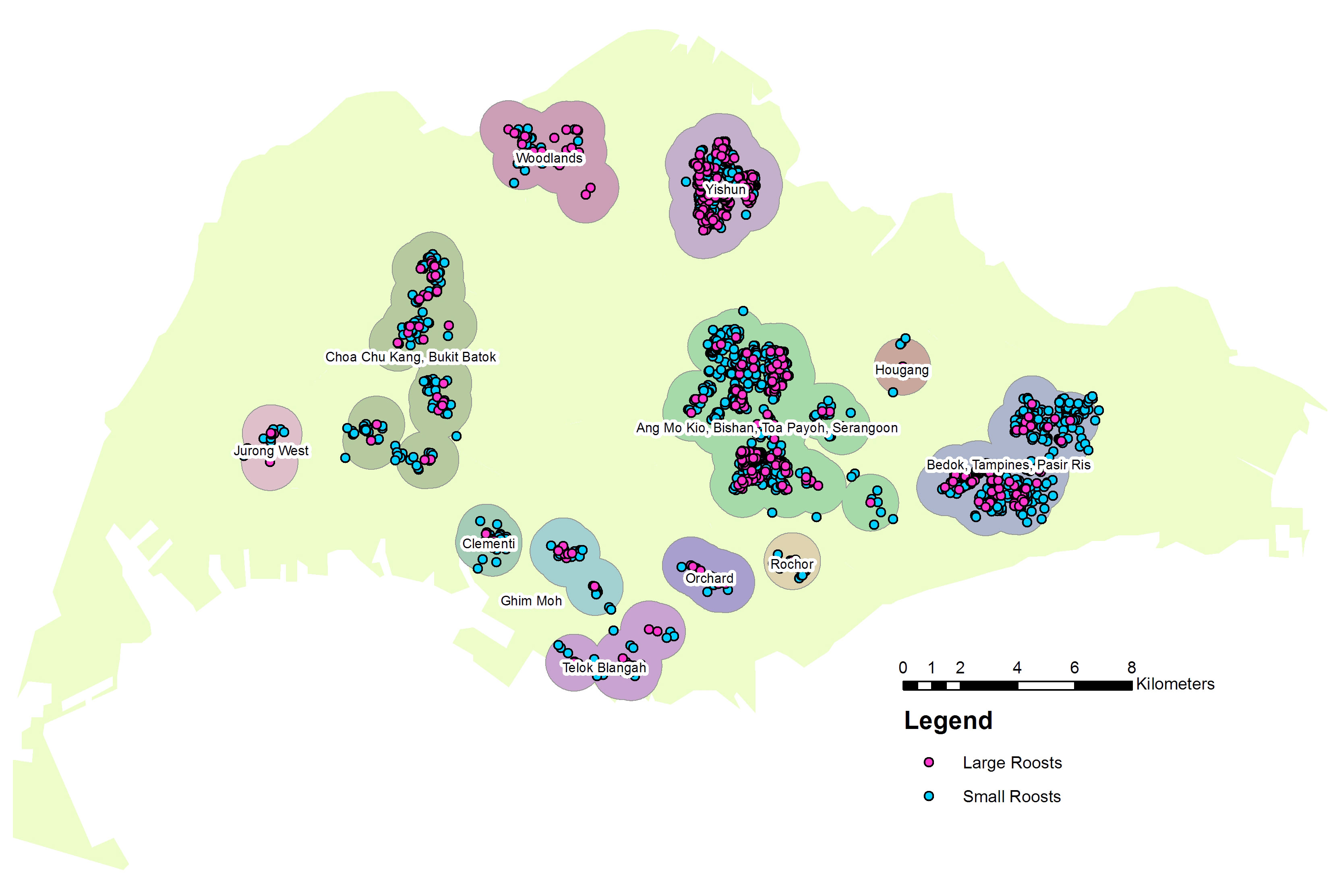

The Javan myna was introduced to Singapore in 1924, and its population has since burgeoned to an estimated 122,000 individuals in 2003.(9) In 2012, a study at the National University of Singapore utilized survey data by Wang Luan Keng to analyze the distribution of roosts in urban areas across the island using a GIS statistical package.(10) Their reconstructed Javan myna roost distribution can be seen in Figure 12 below. |

Fig. 12. Javan myna roost locations in Singapore in 2012, with total range buffer (radius=990.14m) superimposed and colored to show spatial clustering of mynas. Pink dots represent large roosts (>50 birds) while blue dots represent small roosts (<50 birds). Place names are labeled accordingly. (Adapted from Boo et al., 2013)(10) (Data used for map construction is copyrighted. Permission must be sought before reuse) |

| Fig. 13. Javan mynas perched on a rooftop. The Javan myna is now one of the most human-tolerant birds in South-east Asia, and increasingly posing more of a pest problem. (Photo by Gabriel Low) |

Relationships with Humans

Historically, the Javan myna has been kept in captivity in Malaysia and Indonesia, but thanks to its gregarious, bold nature and its penchant for exploiting human refuse as a food source, its range and abundance has grown dramatically. The Javan myna is now considered a pest by many people. The main cause for concern to most people is their tendency to roost in large communal flocks in close proximity to human-inhabited areas, where their noise and droppings are often complained about (Fig. 13).However, in Singapore at least, the Javan myna was not always so tolerant of human proximity. Numbers remained low and distribution largely rural prior to WWII, and as recently as the late 1960s, Ward (1968) described these birds as shy birds of the suburbs.(11) Indeed, it was the common myna (Acridotheres tristis) that was the dominant myna species in Singapore for a long time. However, with increasing urbanization, Hails found in 1985 that Javan mynas outnumbered common mynas by 2.7 times (12), and present-day common mynas are now mainly restricted to rural and beach habitats. It therefore appears that increasing urbanization and availability of human waste as a food source has favoured the Javan mynas’ shift towards a more human-tolerant population.(4)

Taxonomy & Systematics

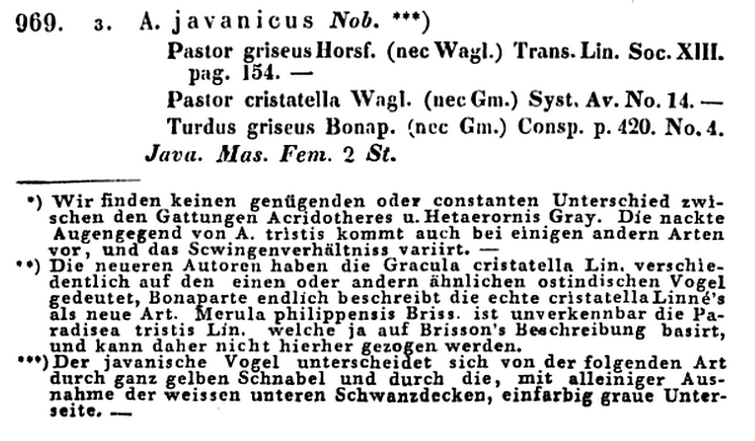

|

| Fig. 14. Screenshot of the original description of the Javan myna published in Museum Heineanum, vol. 1. (Source: Google Book Search) (Public Domain) |

Phylogeny

A hierarchical summary of the taxa within which the Javan myna is placed is provided below:Animalia

- Chordata

- Aves

- Passeriformes

- Muscicapoidea

- Sturnidae (Rafinesque, 1815)

- Acridotheres (Vieillot, 1816)

- A. javanicus (Cabanis, 1851)

- Acridotheres (Vieillot, 1816)

- Sturnidae (Rafinesque, 1815)

- Muscicapoidea

- Passeriformes

- Aves

Type

The Javan myna (A. javanicus) was originally described by Jean Cabanis in 1851 in Museum Heineanum: Verzeichniss der ornithologischen Sammlung des Oberamtmann Ferdinand Heine 1: 205 (Fig. 14).(13) The original description is in German and written in the final footnote of the page. It roughly translates as the following: ‘The Javanese bird differs from the following species by a completely yellow beak and by, with the sole exception of the white undertail coverts, a monochrome gray underside.’Two syntype specimens were collected and designated from Java, Indonesia and are currently deposited at the Museum Heineanum Halberstadt, Halberstadt, Germany.(14)

Taxonomic Confusion

The Javan myna (A. javanicus) and several other Acridotheres species have often been confused taxonomically, no thanks in part to the inconsistent usage of common names associated with this genus of 'crested' mynas.(4) For example, various authors have referred to A. grandis, A. javanicus, and A. cristatellus as Crested Mynas at different times. The commonly mentioned name White-Vented Myna has also been applied variously to A. javanicus and A. cinereus, and is perhaps most confusing as a name because most Acridotheres mynas possess white vents.While Cabanis presumably designated the Javan myna as a species of its own based on morphology, various authors have disagreed over time. Amadon (1956) regarded the pale-bellied myna (A. cinereus), the jungle myna (A. fuscus) and the Javan myna as conspecific under A. fuscus (15), while Sibley and Monroe (1990) awarded the Javan myna full species status on the basis of markedly different features from the jungle myna, especially regarding bill colouration. (16) However, Inskipp et al. (1996) considered the Javan myna, pale-bellied myna, and great myna (A. grandis) to be more similar morphologically to each other than to the jungle myna, and considered them conspecific. (17) Feare and Craig (1999) awarded full specific status to the Javan myna in agreement with Sibley and Monroe (1990), and additionally considered the pale-bellied myna as a full species as well.

Most recently, Wells (2009) considered the allopatric pale-bellied myna to be a distinct species from the Javan myna, but predicted that natural experiments created by the northbound invasion front of Javan mynas encroaching into jungle myna territory in peninsular Malaysia would eventually show jungle mynas and Javan mynas constitute one biological species.(1) Indeed, whereas jungle mynas had been living side by side in Kuala Lumpur with great mynas for almost 20 years without hybridizing, the subsequent introduction of Javan mynas caused a sharp decline in the jungle myna population leading to its local extinction by 2002, all without affecting the great myna population adversely. In the process, suspected jungle-Javan myna hybrids/intergrades were observed at hither-to well known sites for jungle mynas, likely symptoms of the jungle myna population being swamped out genetically by the invading Javan myna.

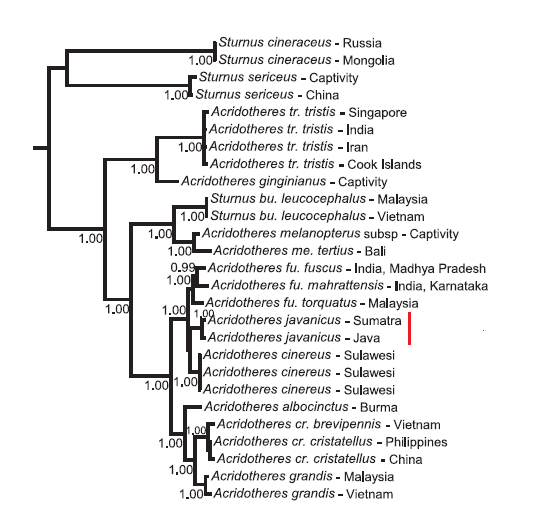

Phylogenetic Relationships

Genbank has barcode sequences available for several genes including COI, COII, ND2 and Fib5. Sequencing of the full Javan myna genome is underway and should be completed by first quarter 2015 (personal communication).Usage of molecular phylogenetic methods has led to some level of clarity regarding the Javan myna's relation to other Acridotheres species and it is now clearer that the pale-bellied myna (A. cinereus), the jungle myna (A. fuscus) and the Javan myna (A. javanicus) should all be considered distinct taxa, based on Bayesian inference analysis using mitochondrial ND2 and COII genes (Fig 15.).(18) However, the exact relationships between these three taxa remain unresolved.

|

| Fig 15. The Bayesian majority rule consensus tree obtained using ND2 and COII mitochondrial genes for the genus Acridotheres. Posterior probabilities equal or higher than 0.95 are indicated at the node. Specimen collection locality is noted next to each individual. The Javan myna's position is indicated by the red line. (Adapted from Zuccon et al., 2008)(18) |

References

- Wells, D. R., 2009. The birds of the Thai-Malay peninsula (Vol. 2). A&C Black. ISBN 978-0-7136-6534-5.

- Kang, N., 1989. Comparative behavioural ecology of the mynas, Acridotheres tristis (Linnaeus) and A. javanicus (Cabanis) in Singapore. Unpublished PhD thesis, National University of Singapore, Singapore.

- Pande, S., 2009. Latin names of Indian birds explained. Mumbai: Bombay Natural History Society and Oxford University Press. p. 506. ISBN 978-0-19-806625-5.

- Feare, C. & A. Craig, 1999. Starlings and Mynas. Princeton University Press, New Jersey. 143-145 pp.

- Xeno-canto Foundation, 2014. Javan myna, Acridotheres javanicus, Cabanis 1851. Hosted on Xeno-canto.org. URL: http://www.xeno-canto.org/species/Acridotheres-javanicus. Accessed on 11 November 2014.

- Yap, C.A.M. & N.S. Sodhi, 2002. Roost characteristics of invasive mynas in Singapore. Journal of Wildlife Management 66: 1118–1127.

- Kang, N., 1992. Radiotelemetry in an urban environment: a study of Mynas (Acridotheres spp.) in Singapore. Pp 633—641 in Priede, I.G. & S.M. Swift (eds.), Wildlife telemetry, Remote monitoring and tracking of animals. Ellis Horwood, Chichester.

- del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.), 2013. Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. URL: http://www.hbw.com/node/60869. Accessed on 2 November 2014.

- Lim, H.C., N.S. Sodhi, B.W. Brook & M.C.K. Soh, 2003. Undesirable aliens: Factors determining the distribution of three invasive bird species in Singapore. Journal of Tropical Ecology, 19(6): 685–695.

- Boo, J.T.C., K.E. Ong, X.R. Ong & E.J.Y. Soh, 2013. Spatial distribution of Javan mynas in Singapore. Unpublished GE3238: GIS Design and Practices project report. National University of Singapore. Singapore, 87pp.

- Ward, P., 1968. Origin of the avifauna of urban and suburban Singapore. Ibis 110: 239–254.

- Hails, C.J., 1985. Studies on problem bird species in Singapore: 1. Sturnidae (mynas and starlings). Unpublished report to the Ministry of National Development, Singapore, 97pp.

- Cabanis, J. L., 1851. Museum Heineanum: Verzeichniss der ornithologischen Sammlung des Oberamtmann Ferdinand Heine. R. Frantz. p205. URL:https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=M_sYAAAAYAAJ. Accessed on 2 November 2014.

- SysTax, 2013. Acridotheres javanicus Cabanis, 1851. Universität Ulm & Ruhr-Universität Bochum. URL: http://www.biologie.uni-ulm.de/cgi-bin/query_all/details.pl?id=116046&stufe=7&typ=ZOO&sid=T&lang=e&pr=nix#herb138591. Accessed on 2 November 2014.

- Amadon, D., 1956. Remarks on the starlings, family Sturnidae. Amer. Mus. Novit. 1247: 1-16

- Sibley, C.G. & B.L. Monroe Jr., 1990. Distribution and taxonomy of the birds of the world. Yale University Press, New Haven and London

- Inskipp, T., N. Lindsey & W. Duckworth, 1996. An annotated checklist of the birds of the Oriental region. Oriental Bird Club, Sandy.

- Zuccon, D., E. Pasquet & Per G.P. Ericson, 2008. Phylogenetic relationships among Palearctic–Oriental starlings and mynas (genera Sturnus and Acridotheres: Sturnidae). Zoologica Scripta, 37(5): 469–481.