|

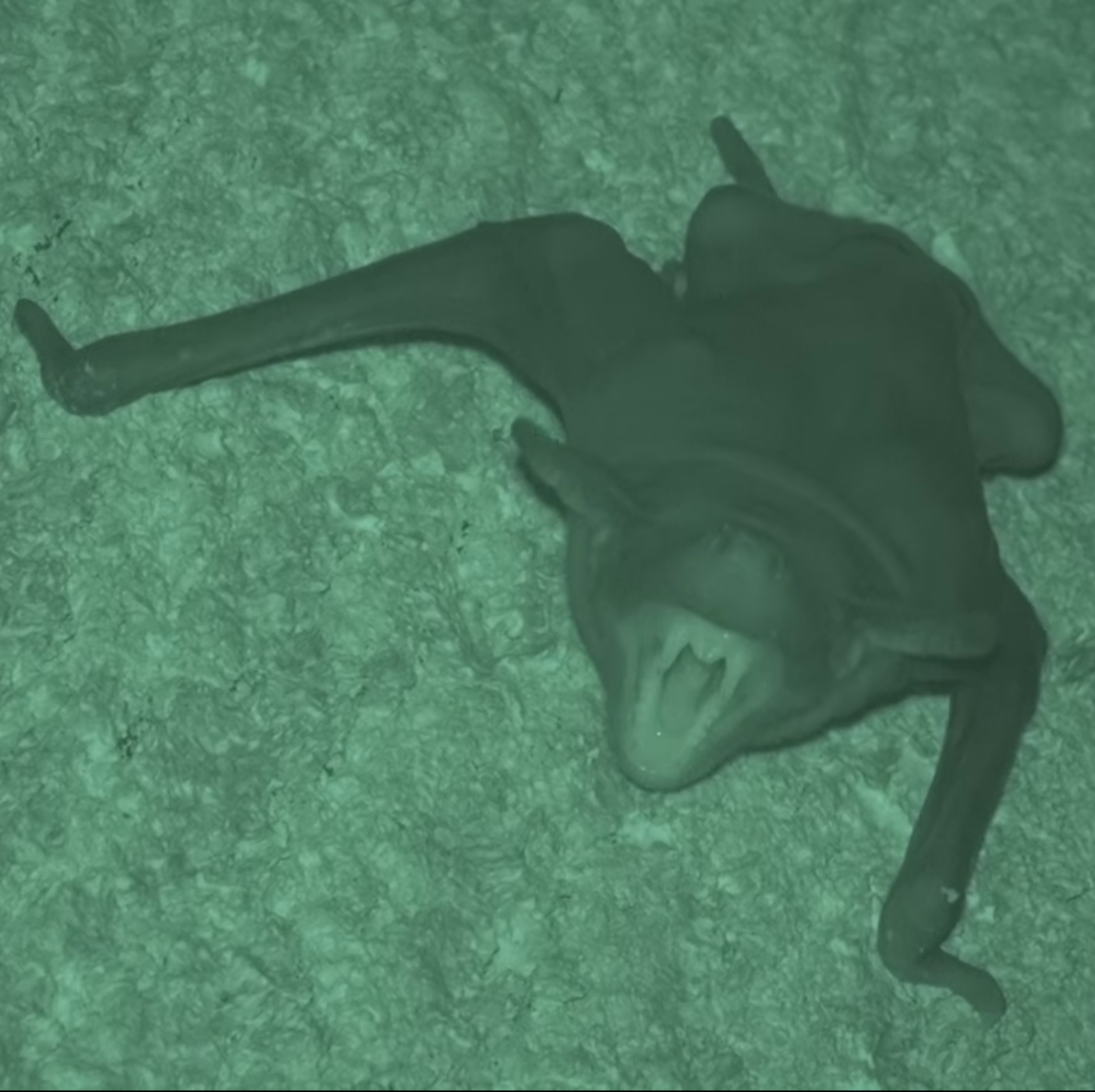

| Figure 1. A naked bulldog bat perched on a tree. Source: Leong et al., 2009. |

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

"It’s a bald bird, it’s a smelly rat - no, it’s the naked bulldog bat."Headline from an article in The Straits Times (Singapore), 19 January 1979[1]

The saying "beauty lies in the eye of the beholder" certainly holds true for the naked bulldog bat (Cheiromeles torquatus). While some may find its appearance unpleasant and strange, others (like myself) find it remarkable. Regardless of how one feels about its appearance, there is no denying it is truly a fascinating creature. Its "hairless" skin, large size and almost noxious smell make it is unlike any bat that people would usually encounter.

The naked bulldog bat is one of the only two species belonging to the genus Cheiromeles which consists of Cheiromeles torquatus and Cheiromeles parvidens. This genus is in the insectivorous bat family, Molossidae, also known as the free-tailed bats so named for their characteristic long tails. Found only in Southeast Asia, the naked bulldog bat is widespread in its range but its abundance differs from area to area[2] . Like all insectivorous microbats, the naked bulldog bat is nocturnal and able to echolocate.

What's in a name?

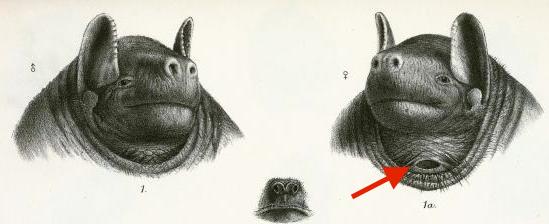

The genus name, "Cheiromeles", comes from the Greek word "cheir" which means "hand." This is in reference to the bat's unusual hindfoot which "has the character and properties of a hand" as described by Horsfield (1824)[3] . "torquatus" comes from the Latin word "torques" which means "collar". This is in reference to the collar of long hairs at the neck region of the naked bulldog bat[4] .

|

|

2. Description

|

General descriptionSize and weight

|

||||

|

Brief physical description[3]

|

||||

|

Cranial and dental features

|

||||

|

Interesting distinguishing features"Nakedness/hairless" skin

|

||||

|

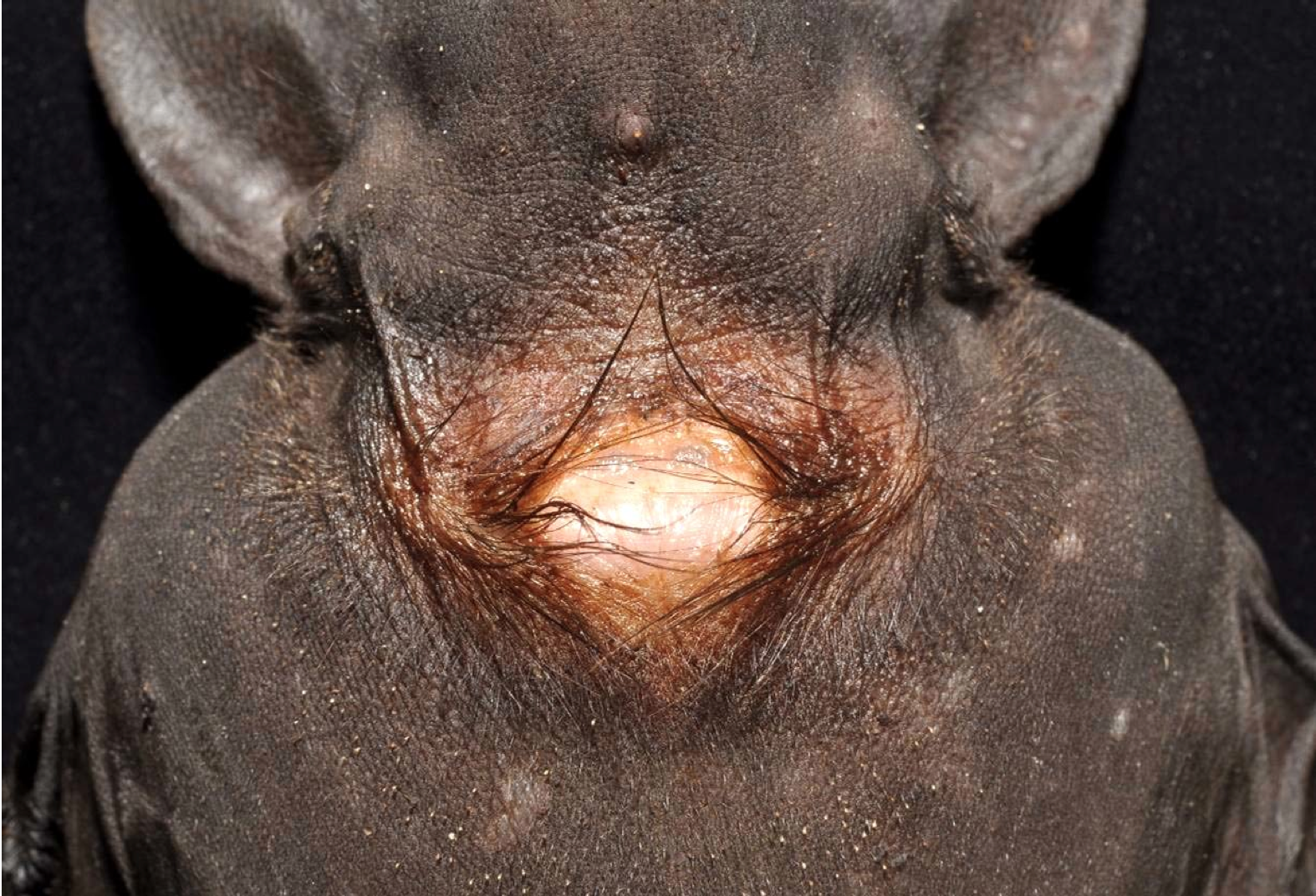

Gular pouch/sac

|

||||

|

Hindfoot

|

||||

|

Subaxillary pouch

|

||||

|

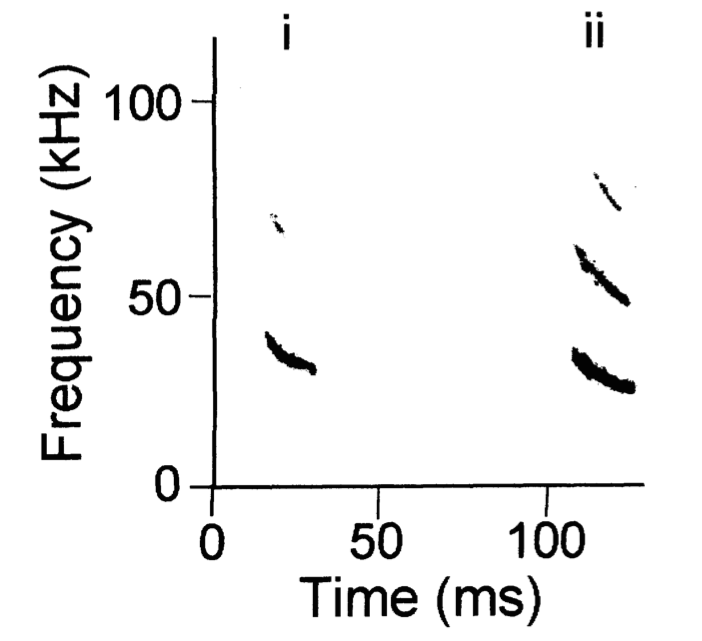

Sonogram of search phase call

|

||||

3. Distribution, status and threats

Southeast Asia

The naked bulldog bat is found only in Southeast Asia and in the following countries: Peninsular Malaysia, southern Thailand, in Indonesia, from Sumatra to Java, and across Borneo, in Philippines only on Palawan island and, in Singapore[16] [17] [18] . According to the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, the conservation status of the naked bulldog bat is listed as "Least Concern". This is because it has a widespread range, and although rare and facing some major threats in some parts of its range, its decline will not be fast enough to be placed in a more threatened category [2]. |

| Figure 14. Global distribution of the naked bulldog bat. Source: Screen capture from IUCN |

Singapore

The last known confirmed roost of the naked bulldog bat in Singapore was in the Bukit Timah Nature Reserve in 2009 [4]. It is hence considered to be in low abundance and highly endangered in Singapore [18]. Over the past 20 years, they have also been sighted at Chestnut drive forest[19] , Seletar reservoir forest, Rifle Range Drive forest and the Macritchie reservoir forest[4].Threats

In Peninsular Malaysia and Borneo, the naked bulldog bat is hunted and eaten by some indigenous tribes [2][29]. Its roosts are also destroyed in an effort to control the species as it is believed to be an agricultural pest of rice crops despite it being insectivorous[2]. The mining of cave habitats for minerals and for swiftlets' nests also disturb roosting bats[20] .Habitat loss is likely to be the largest threat the naked bulldog bat is facing in Southeast Asia and in Singapore.

4. Ecology and Biology

Locomotion

Different bat species have different flight styles. A bat's flight style in turn influences how it hunts for prey and the ecological niche it occupies. The flight style of a bat is determined by the aspect ratio and wing tip index[21] . To put it simply, aspect ratio is the ratio of the width of the wing to its height while a wing tip index measures how sharp the wing tip is. Bats that have a high aspect ratio (long and narrow wings) and wing tip index are fast rapid fliers while those with a low aspect ratio (short and broad wings) fly slower but have much higher maneuverability[22] . Bats with slow, manoeuvrable flight usually forage in more cluttered environments as compared to those fast flying species that forage over wide, open spaces.The naked bulldog bat is capable of exceptionally fast flight[23] . Of all insectivorous bats, it has the highest aspect ratio and wing tip index[24] .

The naked bulldog bat is also unique in that unlike most bats, it is very agile when moving on all fours[25] . For most bats, increased acrobatics in the air came at the cost of land maneuverability as muscles used for walking had little use in flight[26] . However as mentioned earlier unlike other insectivorous bats that have relatively slim hindlegs, the naked bulldog bat has rather broad hindlegs and its long flexible thumb which allow it to easily grip onto trips and climb backwards and upwards despite its body weight.

Watch how easily the naked bulldog bat reverse-climbs up a tree!

Habitat and Roosts

The naked bulldog bat is gregarious which means it lives in roosts with other bats of the same species[27] . Roosts as large as 20,000 individuals have been recorded[28] . They roost in a variety of sites: hollow trees, caves, buildings, rock crevices, and holes in the earth[2][29] [30] .Echolocation and Diet

|

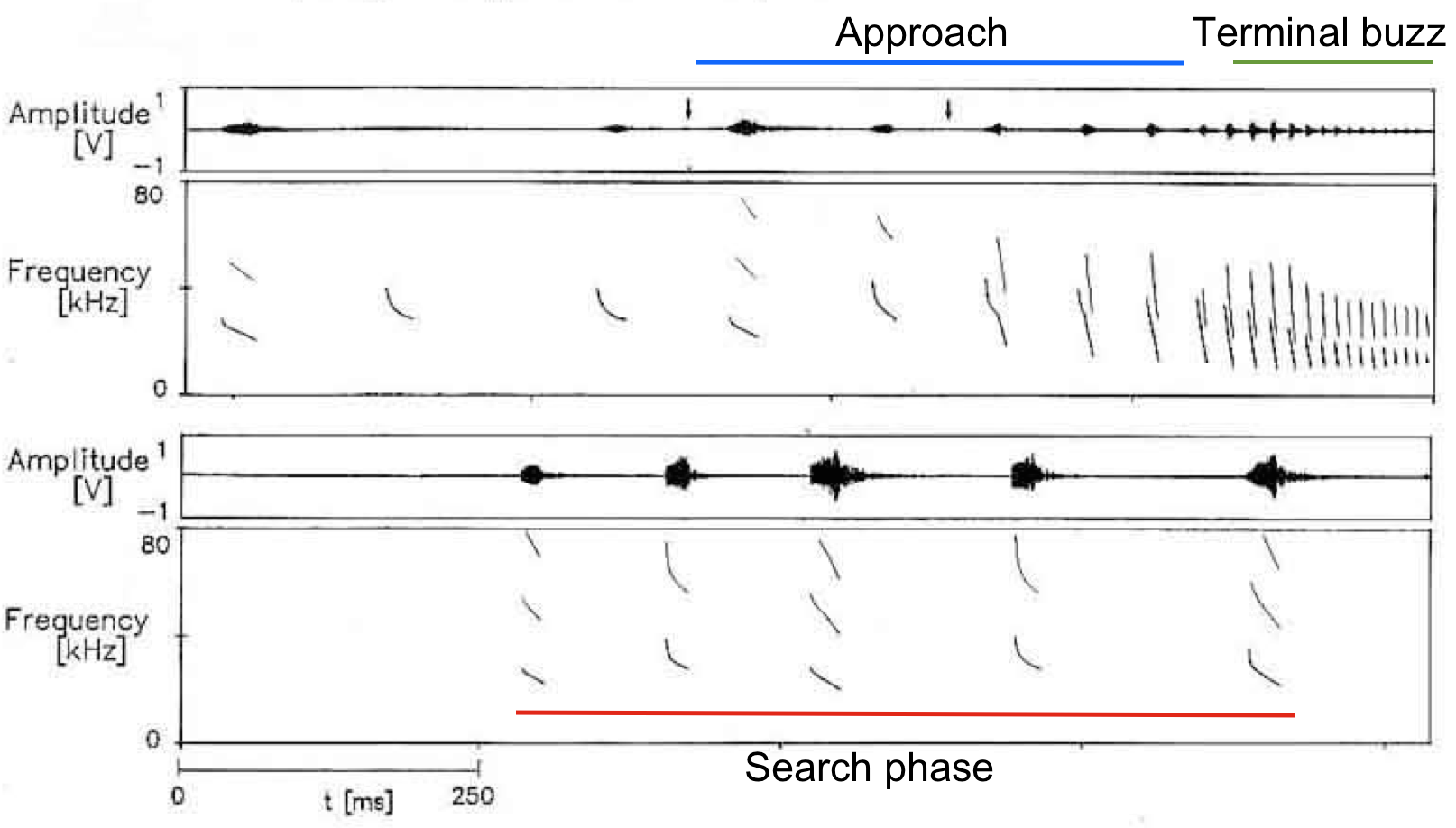

| Figure 15. Sonogram of the search, approach and terminal buzz echolocation call phases of the naked bulldog bat. Source: adapted from Heller, 1996. |

The naked bulldog bat is an aerial-hawking insectivore which means that it forages in open spaces above forests or in clearings, catching prey in flight. It uses echolocation to detect, locate and classify prey as all insectivorous bats do by producing ultrasonic pulses of sound[31] . There are three distinct types of calls bats use: search phase, approach and terminal/feeding buzz (Figure 15). Search phase calls are used for general navigation and searching in uncluttered areas. They have the most consistent call characteristics and hence are best used for species identification. When bats approach prey or are in a more clutter environment, they emit approach calls which are more regular. A feeding/terminal buzz occurs during prey capture or pursuit and consists of short calls that are very quickly emitted together.

When a bat call is visualised on a sonogram, it takes on a shape that can be used to identify the bat to species. Bat calls can be sorted into different frequency structures: Constant Frequency (CF) and Frequency Modulated (FM) or CF-FM which is a mix of both. As the name implies, CF calls look like a constant line that remains at a consistent frequency level while FM calls look like decreasing gradient varying through a range of frequencies[32] . A CF-FM call has elements of both calls. CF calls are usually emitted by bats that forage over open, wide spaces like over canopies or water while FM calls are emitted by those that forage in cluttered environments like a forest understory[33] . Some species, like the naked bulldog bat, are able to modulate their calls depending on the habitat they are in. Their calls become more FM like in cluttered environments as compared to an uncluttered one.

The naked bulldog bat feeds mostly on flying insects like termites, flying ants and moths[6][34] . Its large canines, sharp cusped molars and strong jaw muscles are also indicative that it is able to feed on larger hard-shelled insects like beetles[35] .

5. Taxonomy

Taxonavigation

The classification of the naked bulldog bat is as follows[2]| Kingdom |

Animalia |

| Phylum |

Chordata |

| Class |

Mammalia |

| Order |

Chiroptera |

| Suborder |

Yangochiroptera |

| Family |

Molossidae |

| Genus |

Cheiromeles |

| Species |

Cheiromeles torquatus |

Original description

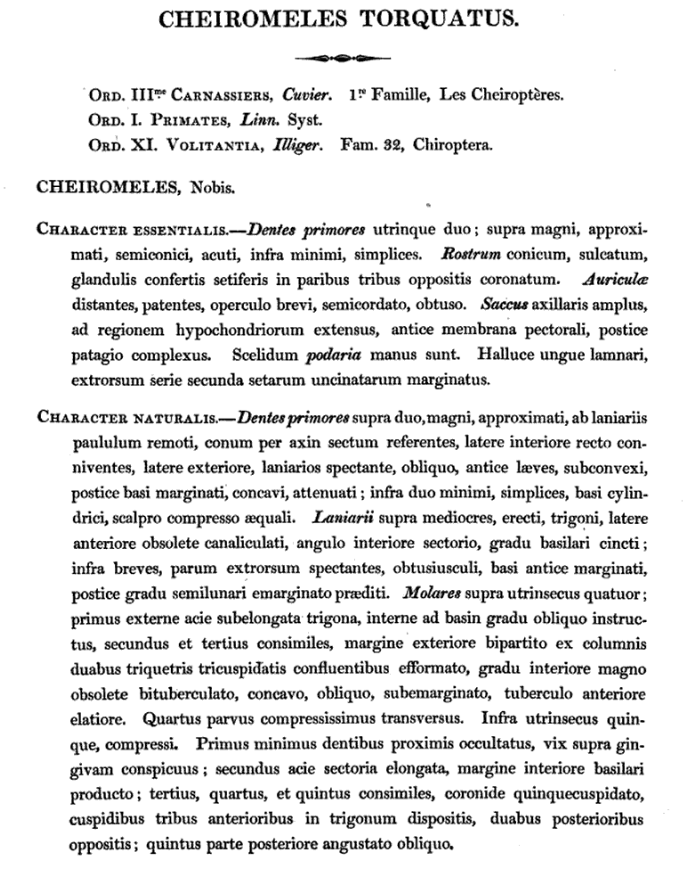

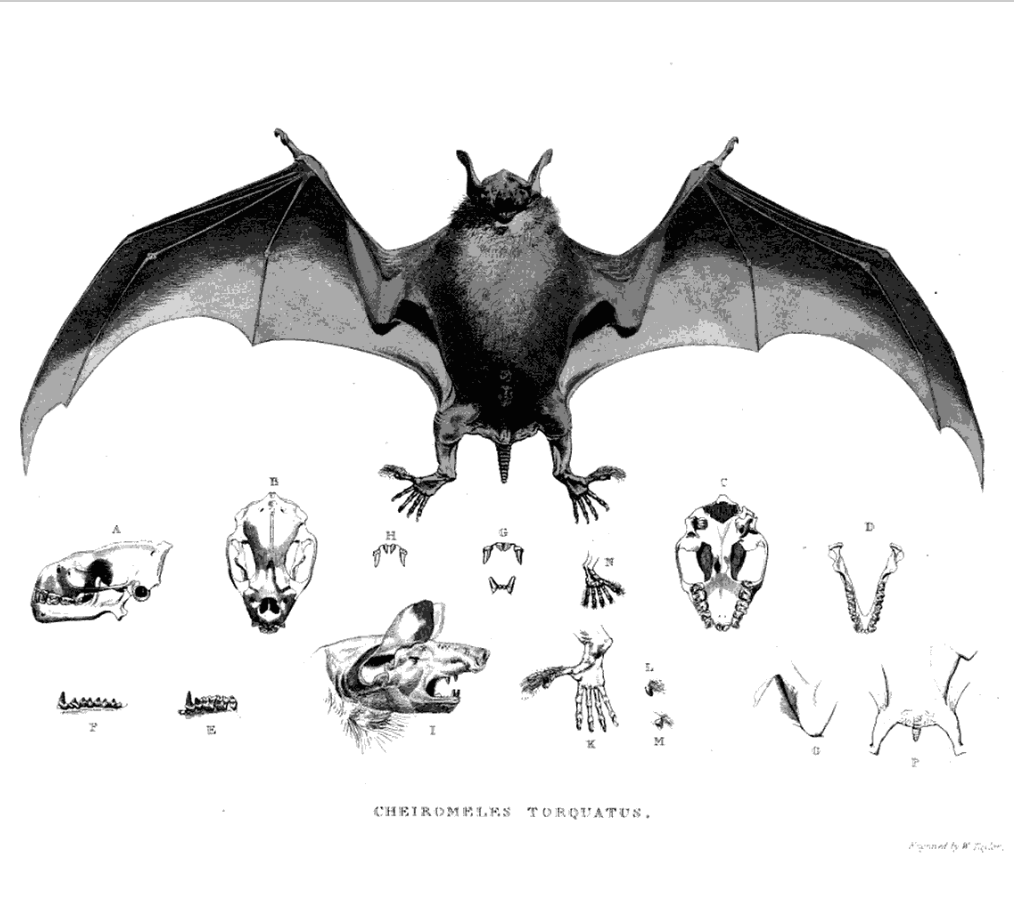

The naked bulldog bat and the genus it belongs, Cheriomeles, was originally described in 1824 by Thomas Horsfield, a physician and naturalist (Figure 11)[3]. The description was extremely detailed and was accompanied by illustrations (Figure 12). |

| Figure 16. Original description of the naked bulldog bat. Source: Biodiversity Heritage Library. Digitised by Smithsonian Libraries. |

|

| Figure 17. Illustration that accompanied the description. Source: Biodiversity Heritage Library. Digitised by Smithsonian Libraries. |

Type Specimen

The holotype for the naked bulldog bat is found in the Natural History Museum (London).The collecting data is as follows:

- Type locality: Indonesia

- Sex: Male

- Life stage: Adult

- Occurrence ID: 17adc2f5-18ee-484e-a268-e4a5b0316bbe

- Catalog Number: 1923.10.7.9

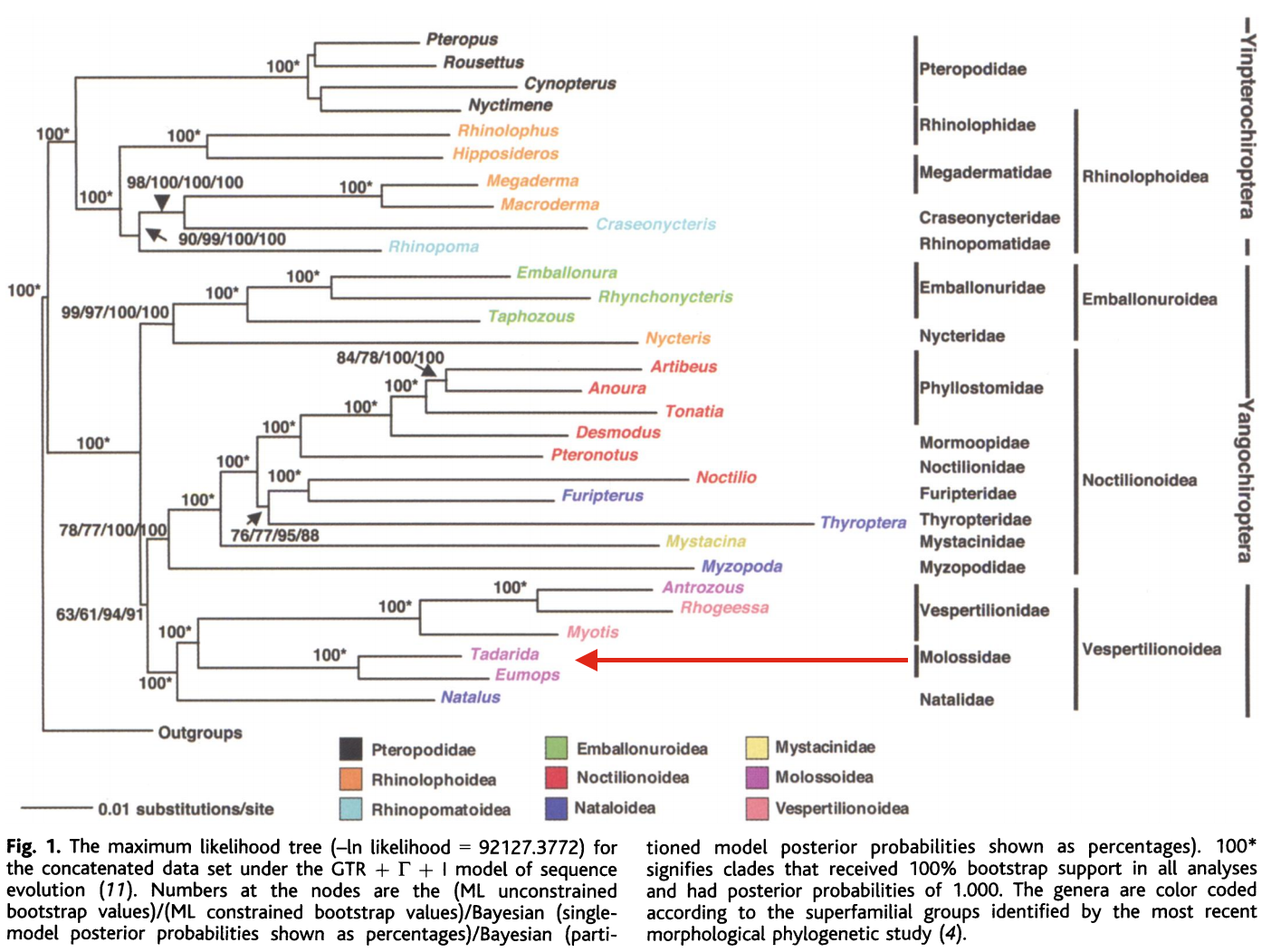

Phylogeny

Bats belong to the order Chiroptera. This order was traditionally divided into the suborders Megachiroptera which consisted of megabats and Microchiroptera consisting of microbats (echolocating bats). However recent molecular evidence has shown that microbats are paraphyletic with bats from the family Rhinolophidae being in the suborder Yinpterochiroptera with megabats and other microbat families being in Yangochiroptera[36] .In a study by Teeling et al. (2005), they analyzed 13.7 kb of nuclear sequence data from portions of 17 nuclear genes from representatives of all bat families and four outgroups. [37] The phylogenetic analysis used a variety of methods that included Maximum Likelihood (ML) unconstrained bootstrap values, ML constrained bootstrap values, Bayesian (single-model posterior) and, Bayesian (partitioned model posterior). Results showed a clear support for the order to be divided into two suborders, hence showing microbats to be paraphyletic and hence for the family Molossidae in the suborder Yangochiroptera (100% bootstrap support in ML analyses; Bayesian posterior probability of 1.000). The Bayesian posterior probability for the placement of Molossidae in the superfamily Vespertillionoidea was relatively high (0.94,0.91) although bootstrap support for ML analyses was rather low. Teeling et al. (2005) noted that morphological and molecular data did conflict in this area and that the use of different molecular data resulted in differing results.

|

| Figure 18. Analysis done for all bat families and four outgroups using 3.7 kb of nuclear sequence data from portions of 17 nuclear genes. Source: adapted from Teeling et al., 2005. |

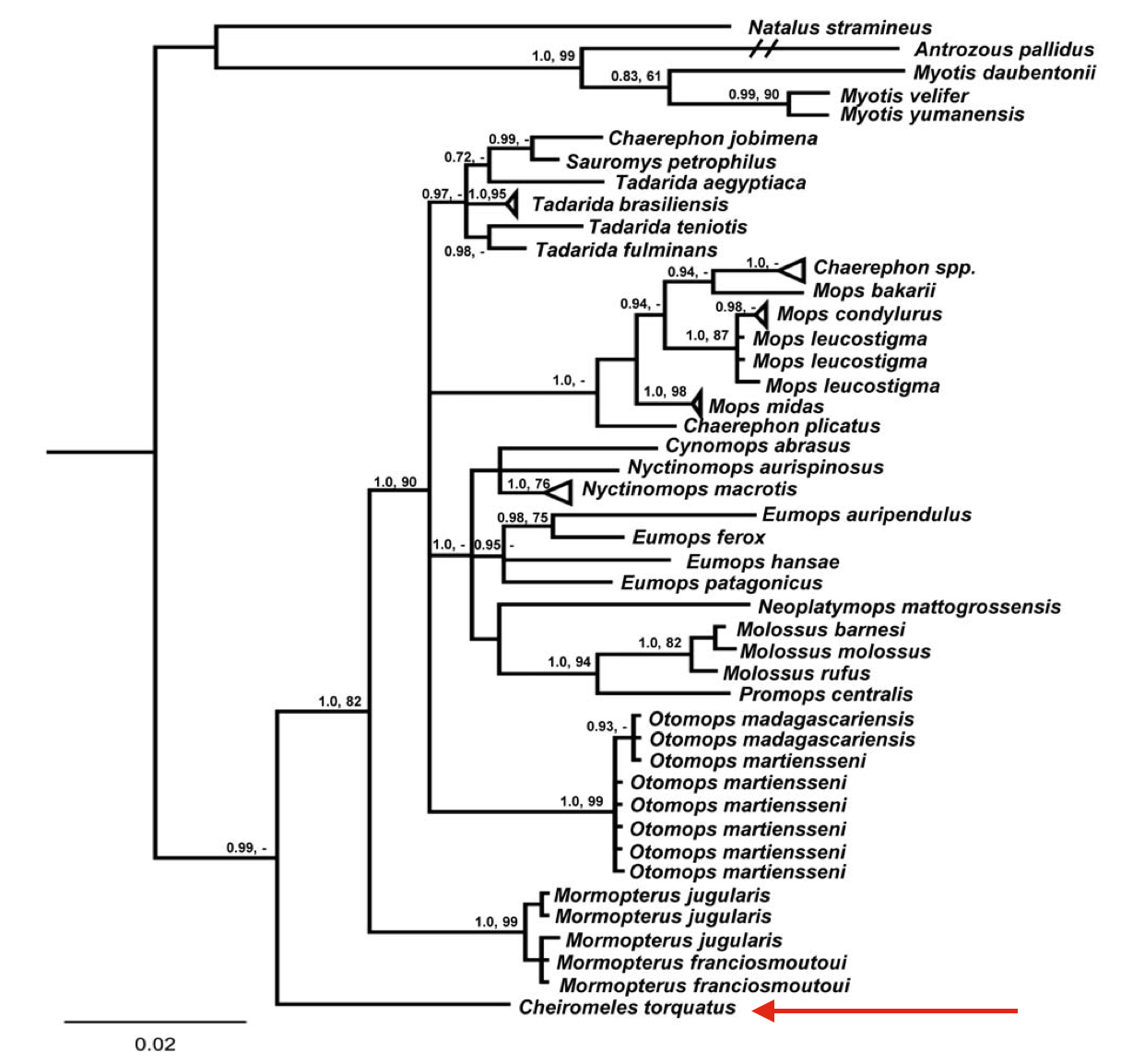

Previous relationships between genera in the family Molissidae were mostly only understood through analysis of morphological data[38] However a recent phylogenetic study has found that previous relationships proposed on morphological data were not supported[39] . A study by Ammerman et al (2013) conducted Bayesian and Maximum Likelihood analyses of Rag2 sequences from 64 molossid bats (from 13 genera, in total 31 species) and five outgroup taxa. Results support Cheriomeles as the most basal lineage in the subfamily Molissinae with a BPP of 0.99 (Figure 17)[39]. This result is particularly interesting as the genus has many unusual characteristics that is not found in other genera.

|

| Figure 19. Bayesian and Maximum Likelihood analysis done for 64 molossid species and five outgroup taxa using Rag2 sequences. Dashes indicate ML BS values less than 70 at locations supported by BPPs Source: adapted from Ammerman et al., 2013. |

DNA barcode

Nucleotide and protein sequences for the naked bulldog bat can be found at The National Center for Biotechnology Information.6. References

- ^ Anonymous, 1979. It’s a bald bird, it’s a smelly rat - no, it’s the naked bulldog bat. The Straits Times (Singapore), 19 Jan.1979.

- ^ Csorba, G., Bumrungsri, S., Francis, C., Bates, P., Gumal, M. & Kingston, T. 2008.Cheiromeles torquatus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2008: e.T4601A11028521. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T4601A11028521.en. Downloaded on 02 November 2016.

- ^ Horsfield, T., 1824. Zoological Researches in Java, and the Neighbouring Islands. Kingsbury, Parbury & Allen, London. 600 pp. + 79 pls.

- ^ Leong, T. M., Teo, S. C., & Lim, K. K. P., 2009. The naked bulldog bat, Cheiromeles torquatus in Singapore-past and present records, with highlights on its unique morphology (Microchiroptera: Molossidae). Nature in Singapore, 2, 215-230.

- ^ Harrison, J. L., 1964. An Introduction to the Mammals of Sabah. The Sabah Society, Kota Kinabalu. ix + 244 pp.

- ^ Heller, K. G., 1995. Echolocation and body size in insectivorous bats: the case of the giant naked bat Cheiromeles torquatus (Molossidae). Le Rhinolophe, 11: 27–38.

- ^ Kingston, T., B. L. Lim & Zubaid Akbar, 2006. Bats of Krau Wildlife Reserve. Penerbit Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. 145 pp.

- ^ Macdonald, D. W. 1995. The encyclopedia of mammals. Andromeda Oxford Ltd., New York, 895 pp.

- ^ Allen, H., 1886. Muscles of the hind-limb of Cheiromeles torquatus. Science, 7(174): 506.

- ^ Lekagul, B. & J. A. McNeely, 1988. Mammals of Thailand (2nd Edition). The Association for the Conservation of Wildlife, Bangkok. LI + 758 pp.

- ^ Freeman, P. W., 1999. Nudity in the Naked Bulldog Bat Cheiromeles. Bat Research News, 40(4): 170–171.

- ^ Hassanloo, Z., M. B. Fenton, J. D. Delaurier & J. L. Eger, 1995. Fur increases the parasite drag for flying bats. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 73(5): 837–842.

- ^ Hose, C., 1929. The Field-Book of a Jungle-Wallah: Being a Description of Shore, River and Forest Life in Sarawak. (Reprinted: 1985, 1986, Oxford University Press). H. F. & G. Witherby, London. vii + 216 pp.

- ^ Kitchener, H. J., 1954b. A further note on the naked bulldog bat. Malayan Nature Journal, 9(1): 26–28.

- ^ Schnitzler, H., & E. Kalko, 2001. Echolocation by Insect-Eating Bats. Bioscience, 51(7): 557-557.

- ^ Francis, C. M., 2008. A Field Guide to the Mammals of South-east Asia. New Holland Publishers (UK) Ltd, London. 392 pp.

- ^ Pottie, S. A., Lane, D. J., Kingston, T., & Lee, B. P. H., 2005. The microchiropteran bat fauna of Singapore. Acta Chiropterologica, 7(2), 237-247.

- ^ Heaney, L.R., Balete, D.S., Dollar, M.L., Alcala, A.C., Dans, A.T.L., Gonzales, P.C., Ingle, N.R., Lepiten, M.V., Oliver, W.L.R., Ong, P.S., Rickart, E.A., Tabaranza Jr., B.R. and Utzurrum, R.C.B. 1998. A synopsis of the mammalian fauna of the Philippine Islands. Fieldiana: Zoology (New Series) 88: 1–61.

- ^ Teo, R. C. H. & S. Rajathurai, 1997. Mammals, reptiles and amphibians in the Nature Reserves of Singapore –diversity, abundance and distribution. Gardens’ Bulletin Singapore, 49(2): 353–425.

- ^ Clements, R., Sodhi, N. S., Schilthuizen, M. and Ng, P. K. L. 2006. Limestone Karsts of Southeast Asia: Imperiled Arks of Biodiversity. BioScience 56(9): 733–742.

- ^ Simmons, J. A., Fenton, M. B., & O'Farrell, M. J. (1979). Echolocation and pursuit of prey by bats. Science, 203(4375), 16-21.

- ^ Norberg, U. M., & Rayner, J. M., 1987. Ecological morphology and flight in bats (Mammalia; Chiroptera): wing adaptations, flight performance, foraging strategy and echolocation. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 316(1179), 335-427.

- ^ Payne, J., C. M. Francis, and K. Phillipps. 1985. A Field Guide to the Mammals of Borneo. Sabah Society, Kota Kinabalu, 332 pp.

- ^ Freeman, P. W., 1981. A multivariate study of the family Molossidae (Mammalia: Chiroptera): Morphology, ecology, evolution. Fieldiana: Zoology, New Series (Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago), 7: 1–173.

- ^ Schutt, W. A. & N. B. Simmons, 2001. Morphological specializations of Cheiromeles (naked bulldog bats; Molossidae) and their possible role in quadrupedal locomotion. Acta Chiropterologica, 3(2): 225–235.

- ^ Riskin, D. K., Bertram, J. E., & Hermanson, J. W. (2005). Testing the hindlimb-strength hypothesis: non-aerial locomotion by Chiroptera is not constrained by the dimensions of the femur or tibia. Journal of Experimental Biology, 208(7), 1309-1319.

- ^ Nowak, R. 1991. Walker's Mammals of the World. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- ^ Medway, L., 1958. 300,000 bats. Sarawak Mus.J.,8:667-679.

- ^ Harrison, J. L., 1954. The wing pouches of the Naked Bulldog Bat. Malayan Nature Journal, 9(2): 66–67.

- ^ Walker, E., 1975. Mammals of the world (3rd edition).Baltimore and London,The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2 vols., xvii + 1500 pp.

- ^ Kingston, T., Jones, G., Akbar, Z., & Kunz, T. H., 2003. Alternation of echolocation calls in 5 species of aerial-feeding insectivorous bats from Malaysia. Journal of Mammalogy, 84(1), 205-215.

- ^ Denzinger, A., Kalko, E. K., & Jones, G. (2004). Ecological and evolutionary aspects of echolocation in bats. Echolocation in bats and dolphins, 311-326.

- ^ Schnitzler, H. U., & Kalko, E. K. (2001). Echolocation by Insect-Eating Bats We define four distinct functional groups of bats and find differences in signal structure that correlate with the typical echolocation tasks faced by each group. Bioscience, 51(7), 557-569.

- ^ Kitchener, H. J., 1954a. A naked bulldog bat. Malayan Nature Journal, 8(4): 165–166, Pl. 31(bottom figure).

- ^ Freeman, P. W., 1979. Specialized insectivory: beetle-eating and moth-eating molossid bats. Journal of Mammalogy, 60(3): 467–479.

- ^ Teeling, E. C., Scally, M., Kao, D. J., Romagnoli, M. L., Springer, M. S., & Stanhope, M. J. (2000). Molecular evidence regarding the origin of echolocation and flight in bats. Nature, 403(6766), 188-192.

- ^ Teeling, E. C., Springer, M. S., Madsen, O., Bates, P., O'brien, S. J., & Murphy, W. J. (2005). A molecular phylogeny for bats illuminates biogeography and the fossil record. Science, 307(5709), 580-584.

- ^ Ammerman, L. K., Lee, D. N., & Tipps, T. M., 2012. First molecular phylogenetic insights into the evolution of free-tailed bats in the subfamily Molossinae (Molossidae, Chiroptera). Journal of Mammalogy, 93(1), 12-28.

- ^ Ammerman, L. K., Brashear, W. A., & Bartlett, S. N. (2013). Further evidence for the basal divergence of Cheiromeles (Chiroptera: Molossidae). Acta Chiropterologica, 15(2), 307-312.

All images used in this web page are used in accordance to Fair Use guidelines. If you are a creator and have an issue with your work displayed on this web page, please contact me at a0115644@u.nus.edu

Figure 1, 5, 6, 7, 9, 11, 12: Leong, T. M., Teo, S. C., & Lim, K. K. P., 2009. The naked bulldog bat, Cheiromeles torquatus in Singapore-past and present records, with highlights on its unique morphology (Microchiroptera: Molossidae). Nature in Singapore, 2, 215-230.

Figure 2: Tigga Kingston. Personal image. Permission granted.

Figure 3: Adapted from Meristogenys69, obtained and accredited under fair use. Modifications: Screen capture of relevant section. URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-3A83XxuLXg

Figure 4: Nurul Ain Elias. Permission pending. URL: http://www.functionalecology.org/view/0/summaries/LaySummariesVol29Iss11.html

Figure 8: Merlin Tuttle Bat Conservation. Permission granted (bat fan). URL: https://merlintuttle.smugmug.com/Low-Resolution/Roosting/i-S4QHNcS

Figure 10: Dobson, G. E., 1878. Catalogue of the Chiroptera in the Collection of the British Museum. Taylor & Francis, London. xlii + 567 pp., Pls. I–XXX. Digitized by the The New York Public Library. URL: http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47da-68ae-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

Figure 13: Kingston, T., Jones, G., Akbar, Z., & Kunz, T. H., 2003. Alternation of echolocation calls in 5 species of aerial-feeding insectivorous bats from Malaysia. Journal of Mammalogy, 84(1), 205-215.

Figure 14: “IUCN Red List Map of Cheiromeles torquatus” by IUCN. URL: http://maps.iucnredlist.org/map.html?id=4601

Figure 15: Heller, K. G., 1995. Echolocation and body size in insectivorous bats: the case of the giant naked bat Cheiromeles torquatus (Molossidae). Le Rhinolophe, 11: 27–38.

Figure 16, 17: Horsfield, T., 1824. Zoological Researches in Java, and the Neighbouring Islands. Kingsbury, Parbury & Allen, London. 600 pp. + 79 pls. Digitised by Smithsonian Libraries URL: http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/ia/zoologicalresear00hors#page/14/mode/1up

Figure 18: Teeling, E. C., Springer, M. S., Madsen, O., Bates, P., O'brien, S. J., & Murphy, W. J. (2005). A molecular phylogeny for bats illuminates biogeography and the fossil record. Science, 307(5709), 580-584.

Figure 19: Ammerman, L. K., Brashear, W. A., & Bartlett, S. N. (2013). Further evidence for the basal divergence of Cheiromeles (Chiroptera: Molossidae). Acta Chiropterologica, 15(2), 307-312