Corvus splendens Vieillot, 1817

Table of Contents

House Crows used to be abundant and found everywhere across Singapore between 1985 and 2003. But in recent years, the numbers have gone down [1]. Where are they now? Find out more in the case study featured on this webpage!

Common names include House Crow, Indian House Crow, Grey-necked Crow, Colombo Crow, Gagak Rumah (in Malay), kaa kaa (in Tamil) [2].

Easily recognised by its black plumage with greyish nape and breast [3], the House Crow has established its breeding populations in more than 25 countries beyond its native range [4] ! Its native range include parts of India, southern Iran, Myanmar and western Yunan (China) [3]. In many introduced areas, it considered to be a pest or an invasive species. An invasive species refers to an organism that is not native to a specific location, and it has the tendency to proliferate in high numbers which can potentially cause net harm (negative impacts) to the environment, human economy and health [5]. What makes it a successful invader?

- This webpage aims to provide a summary of the biology of House Crows for nature-lovers and students to gain some appreciation for these birds even though they have global invasive potential.

- A special feature of the House Crow situation in Singapore is included!

- The taxonomy and systematics section is written in technical language for those who may require species identification and other information.

1. The “shining raven” (Etymology)

The House Crow was first formally described by Vieillot in 1817 and named as Corvus splendens [6] (pronounced as KOR-vus SPLEN-denz).

The generic epithet Corvus is the Latin word for "raven", described by Linnaeus in 1766 [7]. The specific epithet, splendens, is a Latin word meaning "shining", "glittering" or "bright", described by Vieillot in 1817 [6]. The name is likely a reference to the bird’s plumage, described by Vieillot as ‘gray dark pearl’ and ‘very lustrous’ [6].

Click if you are interested to see the original species description in 1817!

Figure 1: Image shows the glossy black plumage of the House Crow with distinct grey areas. Photo by J.M.Garg is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

2. Biology

Diet & Habitat - Eats anything Man eats, lives everywhere Man lives?

The House Crow is often thought to be a bird species that is entirely dependent upon man for its existence [8]. However, this relationship between Man and House Crow is only partially true. Before the arrival of humans, House Crows evolved and survived in its native range (e.g. parts of India) [38] and they are well-suited in natural habitats such as forest edge and coastal mangroves [9]. House Crows typically have an omnivore diet consisting of berries, fruits, small mammals, insects and carrion [3].

Once humans came into the picture, these opportunistic animals were able to exploit the additional food resources provided by human development such as oil palm fruits and kitchen scraps [9]. They also scavenge amongst street debris or rubbish dumps for leftover food or feed on road kills [9]. Their gradual reliance on anthropogenic food sources have contributed to the population increase in many human settlements [10]. Human transport has indirectly facilitated the successful invasion of House Crows to coastal settlements, towns, cities and road plantations in more than 25 countries beyond its native range [18]. Therefore, in today's context, House Crows are reliant on mankind for its survival only to a certain extent. However, its spread and unprecedented success is undoubtedly due to humans.

Roosting behavior - A noisy bunch?

House Crows are known to travel fly considerable distances to form communal roost [9] for a variety of reasons such as easy availability and abundance to food and shelter.

Communal roosting refers to the phenomenon when flocks of thousands or millions of birds congregate in an area for a period of time based on an external signal such as nightfall [11]. It is suggested to bring benefits to young birds as they follow the experienced elders to food sources [11].

However, House Crows in communal roost near human habitation usually cause problems like loud noises and crow droppings [12].

Pre-roost gatherings commonly form at rooftops of tall buildings, sometimes with aerial displays to displace another House crow from its perch [8]. By dusk, the groups join other flocks of House Crows to form large roost gatherings in their favourite trees [8].

Figure 2: Pre-roost gatherings of House Crows on top of mall buildings along the Orchard Road shopping street in Singapore during evening. Photo by Melinda Koh (webpage author).

It was observed that House Crows in Singapore preferred roost trees that are typically above 18 m with large crowns and densities, such as the Angsana tree (Pterocarpus indicus) [13]. House Crow control operations in Singapore include tree pruning and the planting of shorter trees to prevent creation of new roost sites [13].

Reproduction - Overprotective parents?

House Crows are territorial, especially during breeding season. They are known to attack animals or humans who could potentially threaten their nestlings or eggs [12]. Breeding season varies depending on locality [12].

Although House Crows are social, they are monogamous (meaning they pair for life) and they remain in close contact even during non-breeding season [8]!

Figure 3: A breeding pair of House Crows grooming. Photo by J.M.Garg is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

The choice of nesting tree depends on easy availability and abundance to food and shelter. It has been observed that the preferred nesting tree species in Singapore is the Yellow Flame Tree (Peltophorum pterocarpum) which has a large crown volume and density, with upward pointing and V-shaped terminal branches [12]. Nesting areas are also common in trees with higher human traffic, nearer rubbish dumps and food centres [12].

In most cases, there is only one House Crow nest in a single tree [8]. Nest location is typically high up in trees above 4 m to keep it out of reach from predators. Clutch is four or five eggs that are pale blue-green, speckled and streaked with brown [8]. Both partners in a breeding share roles in nest construction, incubation and nest feeding [4].

Figure 4: Eggs of House Crows. Image shows the untidy structure of the nest made of twigs and threads. Photo by J.M.Garg is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Intelligence - A Clever bird?

Tool use in gathering food

Numerous studies have suggested that Corvids may be as intelligent as apes in some tasks, such as using tools to gather food [10]. Corvid refers to any member of the family Corvidae, which include crows, jays, magpies, and the raven. Scientists have been shown that Corvid brains have a total brain-to-body mass ratio equal to that of great apes and slightly lower than in humans [10]!

To study the impact of tool use and the evolution of intelligence, the model species is the New Caledonian crow (Corvus moneduloides) which is actually a related species to the House Crow (Corvus splendens) [14]. Find out more about the intelligence of the New Caledonian crow by clicking the video below!

Video 1: Tool use in New Caledonian crow, a species related to the House Crow. Video obtained from YouTube under fair use.

However, it is interesting to note that a particular genetic study has shown that the relative brain size within the family Corvidae may not be able to explain tool use, innovative feeding strategies nor dispersal success in crows [15].

Vocalisation

House Crows make a wide variety of vocalisations and responses to calls of other species [14]. Vocalisations can be a "caw" (typically flat and toneless, like 'aahh aahh') or a "eh-aw" sound [14]. These vocalisations can vary in number of discrete units or patterns depending on the surrounding events and regions of the subspecies [14]. Although it was speculated that these social birds use a variety of diagnostic calls as vocabulary for communication [8], it remains as a topic of debate whether the crows' communication system constitutes a language [14].

Here are some sample call recordings hosted on xeno-canto.org , click on the embedded players to explore the vocalisations of House Crows!

|

|

|

Host of brood parasites - Perhaps, not so clever after all?

House Crows may outsmart many bird species but it is parasitized by the Asian Koel (Eudynamys scolopaceus). The Asian koel is a brood parasite which lays in eggs in the nests of other bird species, resulting in their hosts taking over the burden of hatching and raising their chicks for them [16]. Watch how the young Koel chick is being taken care of by a pair of House Crows (its host parents) in this interesting video! Observe how the white barrings on the brown feathers of the Koel chick is different from the black feathers on the House Crow chicks shown in Figure 5 below.

Video 2: Koel chicks being fed by House Crows. Video obtained from YouTube under fair use.

Figure 5: House Crow chicks being fed by their parents. Photo by J.M.Garg is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

It was suggested that one of the technique that Koels use to gain access to House Crow nests involve a male Koel distracting the sitting house crow away from its nest, while the female Koel sneaks in to lay its egg [8]. How sneaky!

3. How does a House Crow look like?

A Scientific Description of an adult male Corvus splendens.

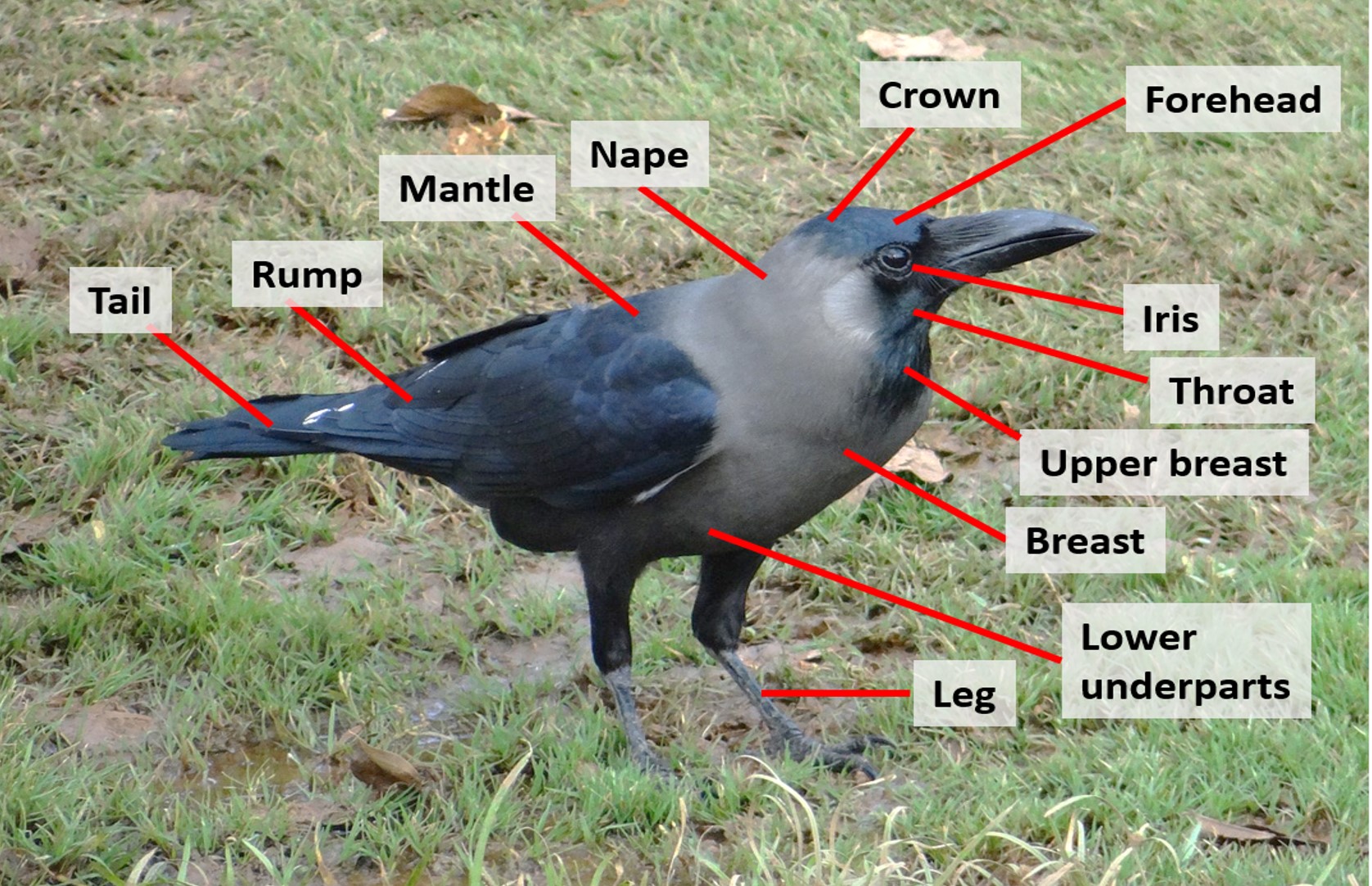

It is easy to identify the House Crow (Corvus splendens) by its colour [8]. Figure 6 is provided as a reference to the description given below. Description is adapted from Madge (2010) [8] unless otherwise stated.

- Nape: grey.

- Crown & Forehead: glossy black, almost flat.

- Irises: blackish brown.

- Bill: black, relatively long and slender with slightly arched culmen.

- Face: glossy black.

- Throat: glossy black.

- Upper breast: glossy black.

- Breast sides: grey, becoming dull blackish approaching to lower underparts.

- Lower underparts: dull blackish.

- Wings: glossy black, relatively broad, especially primaries.

- Mantle: greyish-black, becoming dark grey approaching to rump.

- Rump: dark grey, becoming blackish approaching to tail.

- Tail: Black.

- Legs and toes: black.

Figure 6: Adult House Crow. Body parts are labelled to complement the scientific description given in the text. Original photo is released under CC0 1.0 (Public Domain Dedication). Annotation by Melinda Koh (webpage author).

Female

Both sexes look similar, females are slightly smaller than males [8].

Juvenile

The greyish body parts of juveniles are darker, black plumage looks dull and less glossy compared to adult form [8]. Interior of the open mouth is reddish in juveniles and greyish black in older birds [8].

4. These are NOT House Crows!

House Crows are commonly mistaken as:

- Large-billed Crow (Corvus macrorhynchos) – because they have similar body shape and they may be found in overlapping ranges, including Singapore.

- Western Jackdaw (Coloeus monedula) – because they are similar in plumage, having greyish nape and breast.

- Ravens (several larger-bodied members of the genus Corvus) – there is a common confusion between ravens and crows.

- Adult males of Asian Koel (Eudynamys scolopaceus) – because they have similarities in size and morphology. They may be found in overlapping ranges, including Singapore. House Crows are parasitized by Asian Koels.

Differences between these birds:

1. House Crows are different from Large-billed Crows.

| Large-billed Crow |

House Crow |

|

|

Figure 7: Large-billed Crow (Corvus macrorhynchos) Photo by Alpsdake is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

2. House Crows are different from Western Jackdaws.

| Western Jackdaw |

House Crow |

|

|

Figure 8: Western Jackdaw (Coloeus monedula). Photo by Maxwell Hamilton is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

3. Crows are different from Ravens.

Ravens are generally larger in size compared to crows. Ravens have distinct shaggy throat feathers. Check out this 3-minute video that neatly compiles the differences between crows and ravens!

Video 3: Difference between Ravens and Crows. Video obtained from YouTube under fair use.

4. House Crows are different from the adult males of Asian Koels.

| Adult male of Asian Koel |

House Crow |

|

|

Figure 9: Adult male of Asian Koel (Eudynamys scolopaceus). Photo by Anton Croos is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

5. Where are they found and how do they spread?

Global Distribution

- Native range: Indian Subcontinent, southern Iran, Myanmar and western Yunnan (China) [3].

- Introduced to many areas including: Aden (Yemen), Suez (Egypt), Mombasa (Kenya), Brazil, Phuket (Thailand), Sumatra and Borneo, Vietnam, Malaysia, Singapore, Myanmar, Hong Kong, South Korea and Taiwan [18].

The range of House Crows have increased dramatically since the late 1800s [18]. As of 2015, breeding populations of House Crows were found in 28 countries outside of its native range, at ports and various coastal locations [18]. House Crows are typically found in lowland habitats at elevations <1600 metres, but they have been found to occur in Himalayan military bases that can go up to 4240 metres [19] !

Figure 10: Global distribution of Corvus splendens. Image is a screen capture from The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species global distribution map. Used in accordance with Terms and Conditions for non-commercial use only.

Means of dispersal

Human-facilitated introduction is their main means of dispersal, it can be deliberate or accidental.

Deliberate human-facilitated introduction of House Crows occurred in the form of introduction as a pest-agent or to reduce human refuse [20]. There are official records of three such attempts between the 1840s and 1890s [20, 21, 22]. This led to the species establishment in introduced areas and overland expansion of its population in some areas.

Human-facilitated introduction of House Crows can be accidental, in the form of crows hitch-hiking on ships then transported to various places [18]. It is likely the main factor that contributes to making the House Crow such a successful global invader [18]. As these birds that live in coastal settlements frequently scavenge around ports, the transport via ships could be unintentional [8].

A recent genetic diversity study have shown that the House Crow is generally a low disperser without these hitch-hiking events [23]. The increase in global trade has increased the rate and distance of spread of House Crows from their home range to busy port cities through ship-assisted introductions [18].

Are they threatened?

The House Crow is accorded the conservation status of Least Concern in the IUCN Red List [24]. The species has an extremely large range and it reaches pest status in many countries like Kenya, Yemen, Malaysia and Singapore [4].

House Crows seems to be highly resilient to human attempts in its removal (such as trapping, shooting, use of poisons and nest destruction) because of their ability to switch roost and nest sites quickly and high reproductive capacity [3].

However in their native range, e.g. parts of India, these birds are highly regarded in Hinduism beliefs [25] and they continue to proliferate in high numbers [4].

In Singapore, House Crows are considered as a nuisance and a comprehensive strategic approach is used to bring down crow numbers by limiting their resources coupled with substantial culling [4]. Find out more in the case study featured below!

6. Case Study: House Crows in Singapore

If you have been living in Singapore for the past 20 years, you probably would have some recollection of how House Crows were found in high numbers near residential HDB flats. Today, these birds are found in fewer locations in Singapore and more common in places like the Orchard Road shopping street. Crow culling agencies are not allowed to shoot the birds in tourist areas because it be mistaken as a terror attack and it is difficult to obtain permission to seal off a busy shopping zone for a shooting spree [41].

Figure 11: A House Crow perching on a street light pole along Orchard Road Singapore. Photos (left and right) by Melinda Koh (webpage author).

Originally introduced as a pest-agent from India to Peninsular Malaysia, the House Crow found its way to Singapore by hitch-hiking on ships and established itself in Singapore around 1946 [9]. Urban development and clearance of land in Singapore during 1980s provided additional resources for House Crow, contributing to an overpopulation of crows.

Between 1985 and 2003, Singapore faced the 'House Crow nuisance' problem. Crow population reached 130,000 in 2003 and the cost of culling 50,000 House Crows was almost SGD 1 million [26]! House Crows were known to establish large roost sites (consisting of almost 3000 individuals) near residential areas and they form huge nesting colonies along tall wayside trees [12]. Besides causing frustration among the residents with their loud noises and crow droppings, House Crows attacks were frequent as they may turn aggressive towards pedestrian who walk past their nests [12].

Figure 12: House Crow culling programme in Singapore is done by professional shooters and it is frequently conducted in residential areas. Photo by Choo Yut Shing is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

To bring down the crow numbers, shooting (direct culling technique) is undertaken by the Agri-Food and Veterinary Authority of Singapore (AVA) [12]. However, direct culling is usually done systematically along with other management strategies [4]. Local researchers focused on studying the bird's behavioural ecology in order to come up with management strategies. Crow carcasses from culling activities are collected every week by AVA and sent for blood and DNA testing [personal communication].

With the knowledge of House Crow population size in Singapore [27], the peak-breeding period [28], preferred tree species for roosting [13] and nesting [12], it became possible to estimate the number of crows that need to be culled and combine culling efforts with nest destruction and resource limitation strategies to keep House Crow population numbers at a manageable level [27]. Resource limitation strategies include such as tree pruning, planting of shorter trees near food centres and proper disposal of food waste [12].

This comprehensive strategic approach proved to be rather successful as there is a significant drop in House Crow population after its implementation. Some people attributed the drop in numbers to the crow control operations taken AVA, while others speculated that house crows are deprived of its resources by other competitive introduced species, such as the Javan mynahs (Acridotheres javanicus) [29]. However, biodiversity expert says there is no clear evidence as of now to say that population trends of House Crows and Javan mynahs are related [29].

Figure 13: Several tall trees along the Orchard Road are favourite roost trees of the House Crows (Corvus splendens), Javan mynahs (Acridotheres javanicus) and Asian glossy starlings (Aplonis panayensis) [30]. They can occur in large flocks of hundreds. Photo by Melinda Koh (webpage author).

Currently, House Crows are common at some places including: Orchard Road, Jurong industrial parks, Yishun and Hougang residential areas [personal communication]. Recent reports on House Crow attacks on pedestrians carrying plastic bags could have stemmed from people feeding the birds [31].

Till today, the House Crow is still considered as a pest and it is one of the six species not protected by the law in Singapore under the Wild Animals and Birds Act [1].

The following section on Taxonomy and Systematics is written in technical language and slightly heavy on jargons.

If you wish to skip this section, check out some interesting websites in Useful Links!

7. Taxonomy and Systematics

Taxonavigation

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Aves

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Corvidae

Genus: Corvus

Species: Corvus splendens Vieillot 1817

Original species description

Corvus splendens was first formally described by Louis Jean Pierre Vieillot in 1817 [6].

Figure 14: A screenshot of the original description of Corvus splendens by Vieillot in 1817, published in Nouveau dictionnaire d'histoire naturelle, appliquée aux arts, à l'agriculture, à l'économie rurale et domestique, à la médecine, etc. Vol. 15. Image source from the Biodiversity of Heritage Library, under public domain.

Below is a direct English translation of the original species description:

“The Jackdaw Grey Bengal, Corvus splendens, Vieillot. Size of jackdaws in Europe: forehead, top of head, throat, legs, wings, tail, beak and feet are black; rest of the plumage is like grey dark pearl; very lustrous plumage."

The holotype specimen originated from Bengal, in the eastern part of the Indian subcontinent [6].

Type information

Unfortunately, the holotype specimen for Corvus splendens is currently listed as one of the "types of unknown whereabouts" [33]. No neotype has been designated for Corvus splendens [33].

Subspecies

There are four recognised subspecies with distinct geographic distribution and they are distinguished by overall tones of grey in plumage [8].

The fifth subspecies, Corvus splendens maledivicus, which occurs on Maldives islands, is treated as invalid because its characters suggest mixed ancestry [32].

The following table summarises the information on the subspecies of Corvus splendens, adapted from Madge, 2010 [8].

Type information on subspecies

Below includes type information of subspecies, adapted from Dickson et al. (2004) [33]. It also includes information of the 5th subspecies although it is not formally recognised [33].

- The type specimen of C. s. insolens is currently stored in The Natural History Museum, Tring.

- The type specimen of C. s. protegatus is lost.

- The holotype of C. s. zugmayeri is currently stored at Zoologische Staatssammlung, Münich.

- The holotype of C. s. maledivicus is currently stored at Museum für Naturkunde, Berlin.

Genbank records

Genbank has barcode sequences available for several genes, including COI, ND2, Cytb, and a complete mitochondrial genome (Genbank ascension number KJ766304) of Corvus splendens [34]. It was proposed that the complete mitochondrial genome can be used for population genetic study of crows and addressing issues in taxonomy [34].

Phylogeny

There are several studies of family- and genus-level systematics related to Corvus splendens.

Family-level systematics (phylogenetic relationships within the family Corvidae)

Although the exact inter-relationships of the corvid family is still not well-understood, two findings seem to be well-supported by molecular data:

- The monophyly of the genus Corvus is well-supported [35]

- Corvids are derived from Australasian ancestors and then spread throughout the world [36].

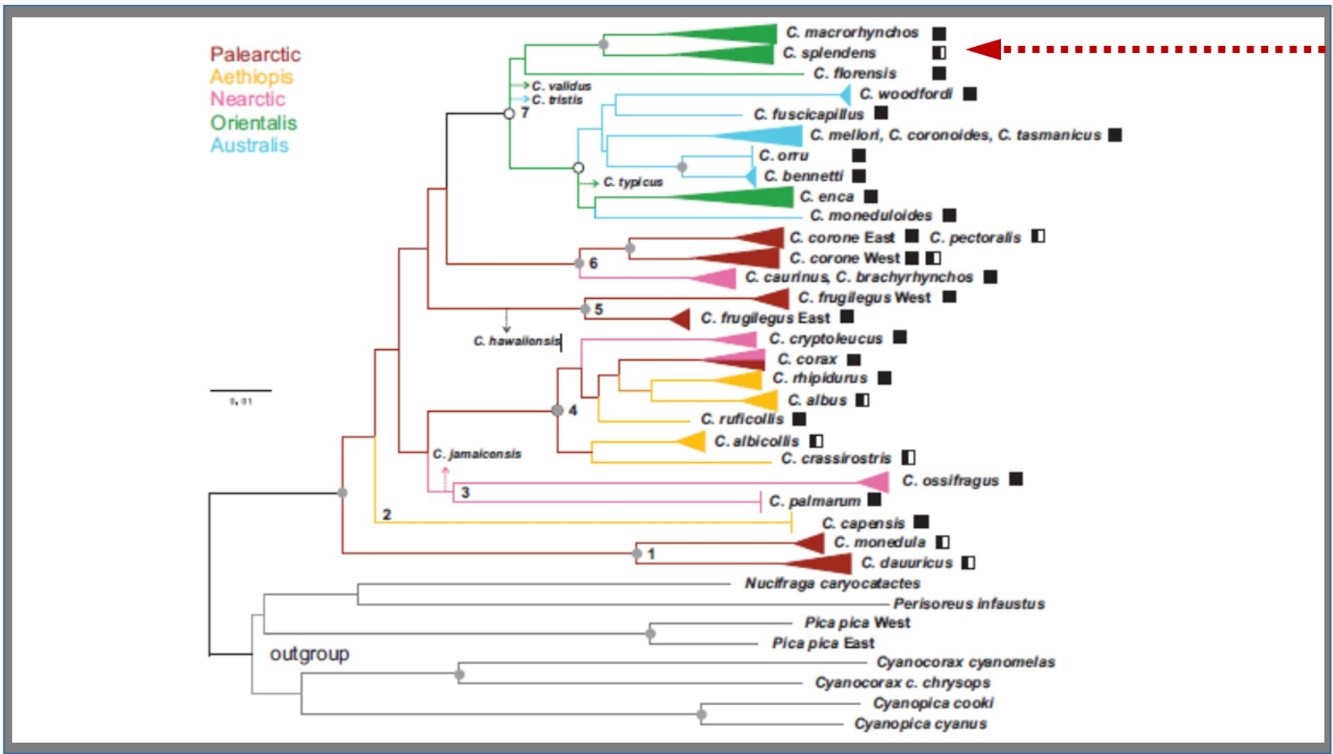

Ericson et al. (2005) [35] estimated the inter-generic phylogenetic relationships of family Corvidae using two nuclear genes (myoglobin and β-fibrinogen) and one mitochondrial gene (cytochrome b). The parsimony analysis of the combined dataset yielded a strict consensus tree that were topologically congruent with the best-fit tree (−ln likelihood=12413.62) in the maximum likelihood analysis. A Bayesian inference analysis was also used to estimate phylogenetic relationships [35]. Based on bootstrap support values for the parsimony analysis and posterior probabilities (>50%) from the Bayesian analysis, the genus Corvus forms a clade with well-supported nodes (MP: 97%, Bayesian: 100%) [35].

Jønsson et al. (2011) [36] investigated diversification of the family Corvidae and estimated the phylogenetic relationships using a chronogram of a combined data set of nuclear introns (ODC and Myo2), nuclear exons (RAG-1 and RAG-2), and mitochondrial (ND2) DNA sequences. Divergence dates were used as tree priors in the Bayesian inference analysis and they were estimated using the relaxed Bayesian molecular clock [36]. Bayesian is useful in dating nodes, and the divergence dates are good priors to come up with good posterior probabilities that leads to less biasness in phylogenetic reconstructions. Based on a 50% majority-rule consensus tree of a Bayesian analysis, there was strong support for an Australian origin for family Corvidae (P > 0.90 for the basal node) [36].

Genus-level systematics (phylogenetic relationships within the genus Corvus)

At present, there is no good systematic approach to the genus.

The concept of three phylogeographic groups in genus Corvus, suggested by Goodwin in 1986 [38], is widely accepted. The three phylogeographic groups refer to the American stock, the Palearctic-African stock and the Oriental-Australian stock [38]. The House Crow (Corvus splendens) is one of the Asian species in the Oriental-Australian stock [38]. Under this concept by Goodwin (1986) [38], species from a geographical area are assumed to be more closely related to each other than to other lineages [38]. However, this is not necessarily applicable to all situations especially with regards to the Australian/Melanesian species [14].

Scientists have also used molecular data, morphological data, and even vocal features as characters [39] to infer phylogenetic relationships within the genus Corvus. Molecular phylogeny with extensive taxon sampling have demonstrated the possibility of subclades within genus Corvus [15, 40].

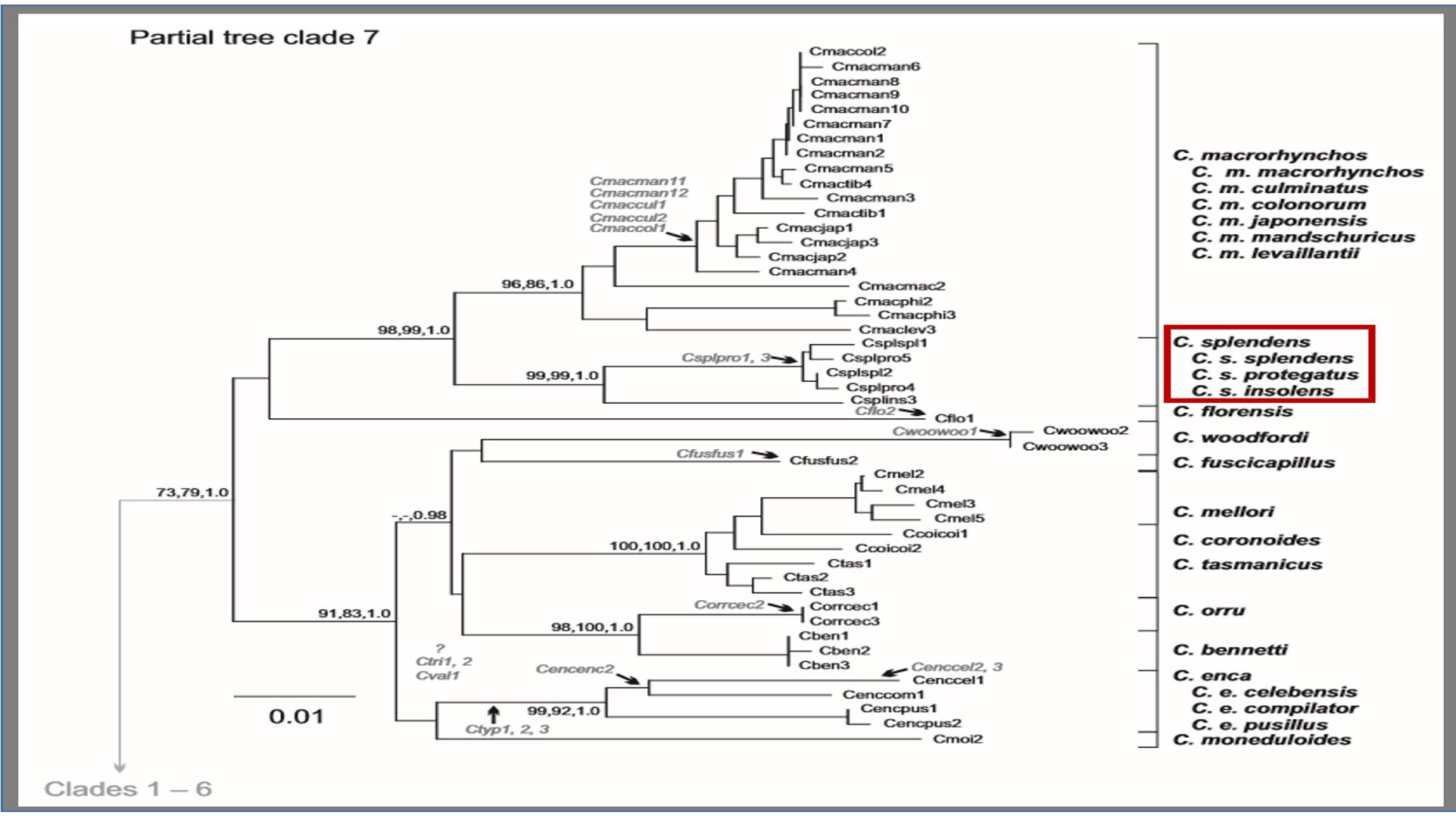

From Haring et al. (2012) [40] unless otherwise stated.

Haring et al. (2012) [40] estimated the inter- and intraspecific variation within the genus Corvus using DNA sequences of mitochondrial control region (mt CR). The mt CR sequences were obtained from 34 out of 40 described species (including subspecies: 56 taxa) in the genus Corvus and seven outgroup species [40]. Since the study by Haring et al (2012) [40] required extensive taxon sampling of museum materials, only a short marker sequence (~650 bp) of the mt CR could be analysed. The short mt marker sequence consists of a partial sequence of the mt CR (positions 693–1308 of the reference sequence of Cyanopica cyanus cyanus, Genbank accession number: AJ458536) and 21 bp of the adjacent tRNA-Phe gene [40]. The Genbank accession numbers for the sequences used in this study, as well as the geographical origins and types of tissue used, are listed in the Appendix of the article by Haring et al. (2012) [40].

The alignment of CR sequences has a length of 704 bp, with gaps treated as fifth character state [40]. Neighbour-Joining (NJ), maximum parsimony (MP), and Bayesian inference (BI) analyses were used to estimate the phylogenetic relationships within the genus Corvus [40]. Nodal support values for NJ and MP trees were calculated by 1000 bootstrap replicates [40].

Figure 15: Neighbour-Joining tree based on mt CR data showing the major lineages of the genus Corvus and geographical occurrences. Nodes obtained bootstrap values (1000 replications) with maximum support in all analyses. Grey circles indicate high node support, which refers to bootstrap value >90% and Bayesian inference (BI) value 1.0; while white circles indicate bootstrap value >70% and BI value of 1.0.

Corvus species that have bicoloured plumage coloration, such as Corvus splendens, is indicated with bicolored squares.

(Reproduced from Haring et al., 2012 [40]; emphasis on Corvus splendens using a red arrow; figure used with permission from corresponding author and publisher).

The study suggested that the genus Corvus is a highly supported monophyletic group with respect to five outgroup genera, as indicated by the grey circle representing high nodal support (NJ: >90%, BI: 1.0) [40] (Figure 15). However, one can say that the result is non-conclusive because the outgroup only consists of seven species from five genera.

The study suggested that within the genus Corvus are seven monophyletic clades, with six of them well-supported [40] (Figure 15). The NJ tree in Figure 15 shows clades 1-6 have grey circles representing high nodal support, but clade 7 is not well-supported (indicated by white circle representing NJ: >70%, BI: 1.0) [40]. Corvus splendens forms a monophyletic group in clade 7 that is the sister group of the monophyletic C. machrorhychos [40] (Figure 15). These two monopyletic groups form a well-supported subclade in clade 7 (as indicated by a grey circle) [40] (Figure 15).

Figure 16: Clade 7 in close-up view. Node support values from NJ, MP, BI analysis are represented at the major nodes (up to species level) in this format: bootstrap value from NJ, bootstrap value from MP, BI value. Bootstrap values (1000 replications) are shown as percentages only if they are greater than 50% and BI values greater than 0.9.

(Reproduced from Haring et al., 2012 [40]; emphasis on monophyletic Corvus splendens using a red box; figure used with permission from corresponding author and publisher).

The monophyly of the Corvus splendens is well-supported by all analyses as shown in Figure 16 (NJ: 99, MP: 99, BI: 1.0). Together with Corvus florensis, C. splendens and C. machrorhychos possibly diverged from another well-supported subclade containing: C. woodfordi, C. fuscicapillus, C. mellori, C. coronoides, C. tasmanicus, C. orru, C. bennetti, C. enca and C. moneduloides [40] (Figure 16). However, the exact relationship between C. florensis and the two subclades remains unresolved because of the poor support value on the phylogenetic tree (nodal support values not shown) [40] (Figure 16). It is suggested that a taxonomic evaluation of the subdivisions within the C. splendens group may require more data [40].

The phylogenetic relationships estimated using a relatively short mt CR marker (~680 bp) in this study by Haring et al. (2012) [40] can only be considered as preliminary and one needs to interpret the data with caution. The average length of mt CR is 1kb [37]. Short DNA barcodes may be able to delineate a large range of species to a certain degree but it may not be able to resolve species that diverged recently due to insufficient characters. In addition, one needs to examine the reasons for using mt CR as a molecular marker. Molecular phylogeny studies based on old museum samples are often limited to using mtDNA because it degrades slower than nuclear DNA [37]. It is widely believed that the variable sequences in mt CR, due to high mutation rates and relaxed selection pressure, can generate some signal about population history over short time [42]. However, it is important to note that the evolutionary rate of mt CR sequences is not entirely clockwise [42] due to the existence of undetected, short-lived mutation hotspots in the hypervariable sites of mt CR [43]. This suggests that mt CR may not be perfect in delimiting species [42]. Therefore, when considering the phylogenetic relationships within Corvus estimated by Haring et al. (2012) [40], it is recommended to perform checks with other datasets, e.g. morphological data.

9. Useful links

- House Crows in Encyclopedia of Life

- House Crows in Avibase (the World Bird Database)

- House Crows in BOLD Systems (Barcode of Life Data Systems)

- House Crows in GBIF (Global Biodiversity Information Facility)

- House Crows in CABI (Centre for Agriculture and Biosciences International)

- House Crows in AVA Public Advisories on Encounters with Wild Animals in Singapore

- House Crows in Singapore Bird Group

- Submit your sightings of House Crows outside their native range in House Crow Monitor

10. References

Text

- [1] Yong, D. L. & K. C. Lim, 2016. A Naturalist's guide to the birds of Singapore. John Beaufoy Publishing, Oxford. 176 pp.

- [2] "Corvus Splendens – Avibase," by Denis Lepage. Avibase – The World Bird Database, n.d. URL: http://avibase.bsc-eoc.org/species.jsp?lang=EN&avibaseid=3986890399CA4 (accessed on 1 Nov 2016).

- [3] Myers, S. & R. Allen, 2009. A field guide to the birds of Borneo. New Holland, New York. 272 pp.

- [4] “Global Invasive Species Database (2016) Species profile: Corvus splendens,“ by Guntram G. Meier. Global Invasive Database. 26 Sep 2007. URL: http://www.iucngisd.org/gisd/species.php?sc=1199 (accessed on 1 Nov 2016).

- [5] Lodge, D. M., S. Williams, H. J. MacIsaac, K. R. Hayes, B. Leung, S. Reichard, R. N. Mack, P. B. Moyle, M. Smith, D. A. Andow & J. T. Carlton, 2006. Biological invasions: recommendations for US policy and management. Ecological Applications, 16(6): 2035-2054.

- [6] de Sève, J. E., 1817. Coquilles. Nouveau dictionnaire d'histoire naturelle, appliquée aux arts, à l'agriculture, à l'économie rurale et domestique, à la médecine, etc (Vol. 15), chez Deterville. Pp 43 – 47.

- [7] Linnaeus, C., 1766. Classis II: Aves. Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio duodecima, reformata, Stockholm. Pp 109-346.

- [8] Madge, S., 2010. Crows and jays. A&C Black, London. 192 pp.

- [9] Davison, G. & Y. F. Chew, 2013. A photographic guide to birds of Peninsular Malaysia and Singapore. New Holland, New York. 144 pp.

- [10] “Corvidae - Meaning Definition Synonym Synopsis,” no author. Social Vocabulary, n.d. URL: http://socialvocabulary.com/defines/Corvidae (accessed on 2 Nov 2016).

- [11] "Communal Roosting," by Paul R. Ehrlich, David S. Dobkin, and Darryl Wheye. Stanford University. 1988. URL: https://web.stanford.edu/group/stanfordbirds/text/essays/Communal_Roosting.html (accessed on 3 Nov 2016).

- [12] Soh, M. C., N. S. Sodhi, R. K. Seoh & B. W. Brook, 2002. Nest site selection of the house crow (Corvus splendens), an urban invasive bird species in Singapore and implications for its management. Landscape and Urban Planning, 59(4): 217-226.

- [13] Peh, K. S. H. & N. S. Sodhi, 2002. Characteristics of nocturnal roosts of house crows in Singapore. The Journal of wildlife management, 1128-1133.

- [14] "Crow," no author. New World Encyclopedia, 2 Apr 2008. URL: http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Crow (accessed on 4 Nov 2016)

- [15] Jønsson, K. A., P. Fabre & M. Irestedt, 2012. Brains, tools, innovation and biogeography in crows and ravens. BMC Evol Biol BMC Evolutionary Biology, 12(1): 72. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-12-72

- [16] Jerdon, T. C. (1862). The Birds of India Being a Natural History of All the Birds Known to Inhabit Continental India: with Descriptions of the Species, Genera, Families, Tribes and Orders, and a Brief Notice of Such Families as are Not Found in India, Making it a Manual of Ornithology Specially Adapted for India, by Thomas Claverhill Jerdon: In Two Volumes. I. Military Orphan Press, Calcutta. 396 pp.

- [17] Begum, S., A. Moksnes, E. Røskaft & B. G. Stokke, 2011. Factors influencing host nest use by the brood parasitic Asian Koel (Eudynamys scolopacea). Journal of Ornithology, 152: 793–800.

- [18] Ryall, C., 2010. Further records and updates of range expansion in house crow Corvus splendens. Bulletin of the British Ornithologists’ Club, 130: 246-254.

- [19] Dos Anjos, L., S. J. S. Debus, S. C. Madge & J. M. Marzluff, 2009. Family corvidae (crows). Handbook of the Birds of the World Bush-shrikes to Old World Sparrows, 14: 494-641.

- [20] Willey, A., W. H. Treacher, E. V. Carey, C. W. H. Cochrane, A. D. Neubronner & O. Marks, 1903. Acclimatization of Ceylon crow Corvus splendens in the Malay Peninsula. Spolia Zeylandica, 1: 23-35.

- [21] Vaughan, J. H., 1930. The birds of Zanzibar and Pemba. Ibis, 72(1): 1-48.

- [22] Barnes, L., 1893. On the birds of Aden. Ibis, 35(1): 57-84.

- [23] Krzemińska, U., R. Wilson, B. K. Song, S. Seneviratne, S. Akhteruzzaman, J. Gruszczyńska, W. Świderek, T. S. Huy, C. M. Austin & S. Rahman, 2016. Genetic diversity of native and introduced populations of the invasive house crow (Corvus splendens) in Asia and Africa. Biological Invasions, 18(7): 1-15.

- [24] BirdLife International. 2012. Corvus splendens. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2012: e.T22705938A38367804. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.20121.RLTS.T22705938A38367804.en (accessed on 2 Nov 2016).

- [25] Savage, C., 2015. Crows: Encounters with the wise Guys of the Avian World. Greystone Books Ltd, Vancouver. Pp. 136.

- [26] Sodhi, N. S. & I. Sharp, 2006. Winged invaders: pest birds of the Asia Pacific with information on bird flu and other diseases. SNP Reference.

- [27] Brook, B. W., N. S. Sodhi, M. C. Soh, & H. C. Lim, 2003. Abundance and projected control of invasive house crows in Singapore. The Journal of wildlife management, 67(4): 808-817.

- [28] Siew, Y. C., F. W. Fong, S. M. Ng & S. K. Poon, 1980. Nest dispersion of the house crow, Corvus splendens Vieillot. Tropical Ecology and Development, 1980: 677-682.

- [29] “Jury's out on the crow issue,” by Lim Yi Han. My Paper. 18 Sep 2014. URL: http://mypaper.sg/top-stories/jurys-out-crow-issue-20140918 (accessed on 1 Nov 2016).

- [30] “Why are there so many freaking noisy pooping birds in Orchard Road?” by Belmont Lay. Mothership.SG, 11 July 2015. URL: http://mothership.sg/2015/07/why-are-there-so-many-freaking-noisy-pooping-birds-in-orchard-road/ (accessed on 8 Nov 2016)

- [31] “Crows swoop down on unsuspecting people in Hougang,” by Ronald Loh. AsiaOne, 18 Jan 2015. URL: https://www.google.com.sg/#q=Crows+swoop+down+on+unsuspecting+people+in+Hougang&tbm=nws (accessed on 1 Nov 2016).

- [32] Madge, S. (2016). House Crow (Corvus splendens). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. (retrieved from http://www.hbw.com/node/60770 on 9 November 2016).

- [33] Dickinson, E. C., R. W. R. J. Dekker, S. Eck & S. Somadikarta, 2004. Systematic notes on Asian birds. 45. Types of the Corvidae. Zool. Verh. Leiden, 350: 111-148.

- [34] Krzeminska, U., R. Wilson, S. Rahman, B. K. Song, H. M. Gan, M. H. Tan & C. M. Austin, 2016. The complete mitochondrial genome of the invasive house crow Corvus splendens (Passeriformes: Corvidae). Mitochondrial DNA Part A, 27(2), 974-975.

- [35] Ericson, P. G., A. L. Jansén, U. S. Johansson & J. Ekman, 2005. Inter‐generic relationships of the crows, jays, magpies and allied groups (Aves: Corvidae) based on nucleotide sequence data. Journal of Avian Biology, 36(3), 222-234.

- [36] Jønsson, K. A., P. H. Fabre, R. E. Ricklefs & J. Fjeldså, 2011. Major global radiation of corvoid birds originated in the proto-Papuan archipelago. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(6), 2328-2333.

- [37] Arif, I. A. & H. A. Khan, 2009. Molecular markers for biodiversity analysis of wildlife animals: a brief review. Animal Biodiversity and Conservation, 32 (1), 9-17.

- [38] Goodwin, D., 1986. Crows of the world. British Museum. London.

- [39] Laiolo, P. & A. Rolando, 2003. The evolution of vocalisations in the genus Corvus: effects of phylogeny, morphology and habitat. Evolutionary Ecology, 17(2), 111-123.

- [40] Haring, E., B. Däubl, W. Pinsker, A. Kryukov & A. Gamauf, 2012. Genetic divergences and intraspecific variation in corvids of the genus Corvus (Aves: Passeriformes: Corvidae)–a first survey based on museum specimens. Journal of Zoological Systematics and Evolutionary Research, 50(3), 230-246.

- [41] “Singapore Takes on Crows; One Down, 34,999 to Go,” by Seth Mydans. AsiaOne. 8 Nov 2006. URL: http://www.nytimes.com/2006/11/08/world/asia/08singapore.html (accessed on 22 Nov 2016).

- [42] Galtier, N., B. Nabholz, S. Glémin & G. D. D. Hurst, 2009. Mitochondrial DNA as a marker of molecular diversity: a reappraisal. Molecular ecology, 18(22), 4541-4550.

- [43] Stoneking, M., 2000. Hypervariable sites in the mtDNA control region are mutational hotspots. The American Journal of Human Genetics, 67(4), 1029-1032.

Images

- Cover photo: Photograph by webpage author, Melinda Koh, on 3 Nov 2016.

- Figure 1: “House Crow (Corvus splendens),” by Dhruvaraj S. Wikimedia Commons. URL: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Corvus_splendens_-_House_Crow.jpg (accessed on 7 Nov 2016).

- Figure 2: Photograph by webpage author, Melinda Koh, on 3 Nov 2016.

- Figure 3: “House Crows (Corvus splendens) grooming in Kolkata,” by J.M.Garg. Wikimedia Commons. URL: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Corvus_splendens_-_House_Crow.jpg (accessed on 7 Nov 2016).

- Figure 4: “House Crow eggs,” by J.M.Garg. Wikimedia Commons. URL: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:House_Crow_eggs_I_IMG_1890.jpg (accessed on 7 Nov 2016).

- Figure 5: “House Crow(Chicks)” by J.M.Garg. Wikimedia Commons. URL: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:House_Crow(Chicks)_I_IMG_0175.jpg (accessed on 7 Nov 2016).

- Figure 6: “Bird, Indian House Crow” by sarangib. Pixabay. URL: https://pixabay.com/en/bird-indian-house-crow-323956/(accessed on 7 Nov 2016).

- Figure 7: “Corvus macrorhynchos (Mount Ontake)” by Alpsdake. Wikimedia Commons. URL: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Corvus_macrorhynchos_(Mount_Ontake).JPG (accessed on 7 Nov 2016).

- Figure 8: “An adult Jackdaw on Ham Common, London Borough of Richmond upon Thames, England,” by Maxwell Hamilton. Wikimedia Commons. URL: https://sco.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Coloeus_monedula_-Ham_Common,_London_Borough_of_Richmond_upon_Thames,_England-8.jpg (accessed on 7 Nov 2016).

- Figure 9: “Asian Koel (Eudynamys scolopaceus) – Male” by Anton Croos. Wikimedia Commons. URL: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Asian_Koel_(Eudynamys_scolopaceus)_-_Male.JPG (accessed on 7 Nov 2016).

- Figure 10: “IUCN Red List Map of Corvus splendens,” by IUCN, IUCN. URL: http://maps.iucnredlist.org/map.html?id=22705938 (Accessed on 6 Nov 2016)

- Figure 11: Photograph by webpage author, Melinda Koh, on 3 Nov 2016.

- Figure 12: "Crow Culling" by Choo Yut Shing. Flickr. URL: https://www.flickr.com/photos/25802865@N08/14082732042 (accessed on 7 Nov 2016)

- Figure 13: Photograph by webpage author, Melinda Koh, on 3 Nov 2016.

- Figure 14: Screenshot of species description of Corvus splendens by Vieillot 1817 [6], available in the Biodiversity Heritage Library.

- Figure 15: Figure 1 by Haring et al. (2012) [40]

- Figure 16: Figure 4 by Haring et al. (2012) [40]

Videos

- Video 1: “How Smart Are Crows? | ScienceTake | The New York Times” by The New York Times. The New York Times Youtube Channel, 10 Apr 2014. URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s2IBayVsbz8(accessed on 7 Nov 2016).

- Video 2: “NCBS lab focus1: Koels and crows - brood parasitism” by TheNCBSnewsteam's channel. TheNCBSnewsteam's Youtube channel. URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GtCQAOStdFM (accessed on 7 Nov 2016).

- Video 3: “Ravens vs Crows, they’re different!” by theravendiaries. Theravendiaries Youtube channel. URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=guBwMUAWAJI (accessed on 7 Nov 2016).

Call Recordings

- Call Recording 1: “XC308330 · House Crow · Corvus splendens splendens,” by Yogesh Patel. Xeno-canto Foundation, 24 Mar 2016. URL: http://www.xeno-canto.org/308330 (accessed on 22 Nov 2016).

- Call Recording 2: "XC211561 · House Crow · Corvus splendens protegatus," by Hans Matheve. Xeno-canto Foundation, 23 Dec 2014. URL: http://www.xeno-canto.org/211561 (accessed on 22 Nov 2016).

- Call Recording 3: "XC207638 · House Crow · Corvus splendens protegatus," by Mike Nelson. Xeno-canto Foundation, 11 Dec 2014. URL: http://www.xeno-canto.org/207638 (accessed on 22 Nov 2016).

Last updated by Koh Zheng Min Melinda (koh.zheng.min94[at]u.nus.edu) on 23 Nov 2016.