Table of Contents

Watch this video on the conservation of baby fruit bats!

Back to top

1. Ecology

1A. Behaviour

Have you seen their large eyes?The lesser dog-faced fruit bat usually cluster in small groups and forage with their keen sense of smell and sight. Unlike Microchiroptera bats, Megachiroptera bats are not capable of laryngeal echolocation as such a mechanism is too energetically expensive to retain. So, the lesser dog-faced fruit bat has its distinctive large eyes for smooth navigation at night.

In addition, the combination of sound and sight is required for the navigation of the lesser dog-face fruit bat. In a study (Heffner et al. 2008), it was shown that hearing is used to direct eyes to source of sound for sound localization.

|

| Taken by Doug Wechsler, under Some Rights Reserved |

Back to top

Sleeping on beds is too boring.

All animals need to rest after a long day of feeding - bats are no different! As you may have seen on television or in movies, bats have very peculiar resting (roosting) behaviour. In the day, the lesser dog-faced fruit bat finds shelter in shaded trees, tree-ferns and near entrances of caves.

|

Roosting behaviour

|

Back to top

The Perfect Life: Make a home and find a mate

|

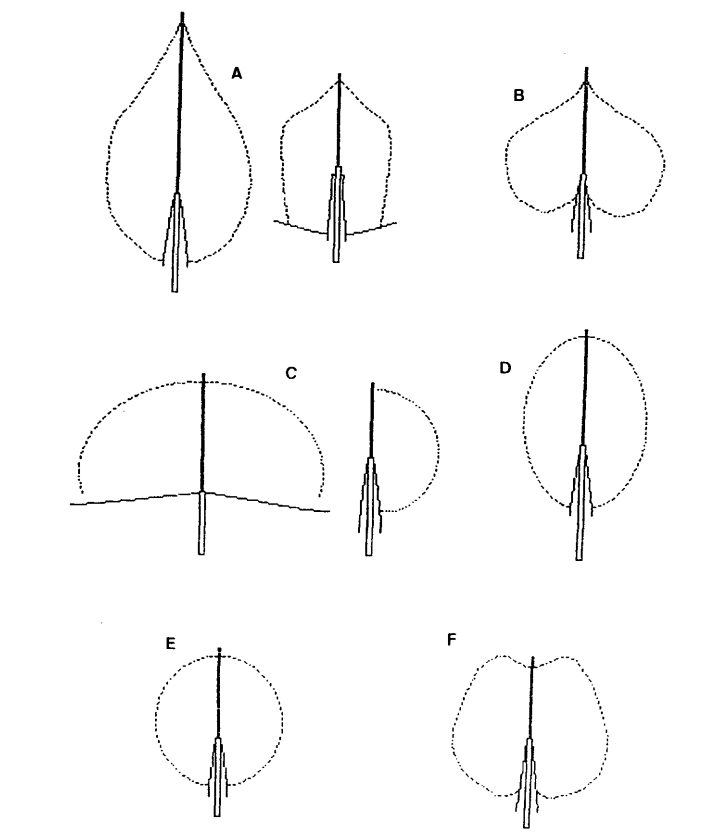

| [A] to [F] are variants of Palmate type tents. (Tan et al. 1997) |

Other than hanging upside-down in a tree, the lesser dog-faced fruit bat may make their own homes, known as roost tents, by chewing and collapsing leaves, stems and flower clusters. In Singapore and Malaysia, folded leaves of palms are used. To date, there are 4 known types of tents constructed by the furry lesser dog-faced fruit bat.

Types of tents

- Palmate

- Umbrella

- Conical

- Apical

- Apical and stem

These tents serve to keep the furry little bats from vicious predators and also shelters them from wind and rain. An interesting fact about roost tents: Males make tents and recruit females (Tan et al, 1997). Males are also observed to have high roost fidelity as a resource defence strategy (Chaverri and Kunz 2006). Females will then choose males based on roost quality. Thus, males have high productivity pay-off if they successfully recruit females and exclude other males from roosts.

Back to top

1. Ecology | 2. Description | 3. Distribution & Habitat | 4. Importance of bats around the world | 5. Conservation | 6. Taxonomy | 7. References |

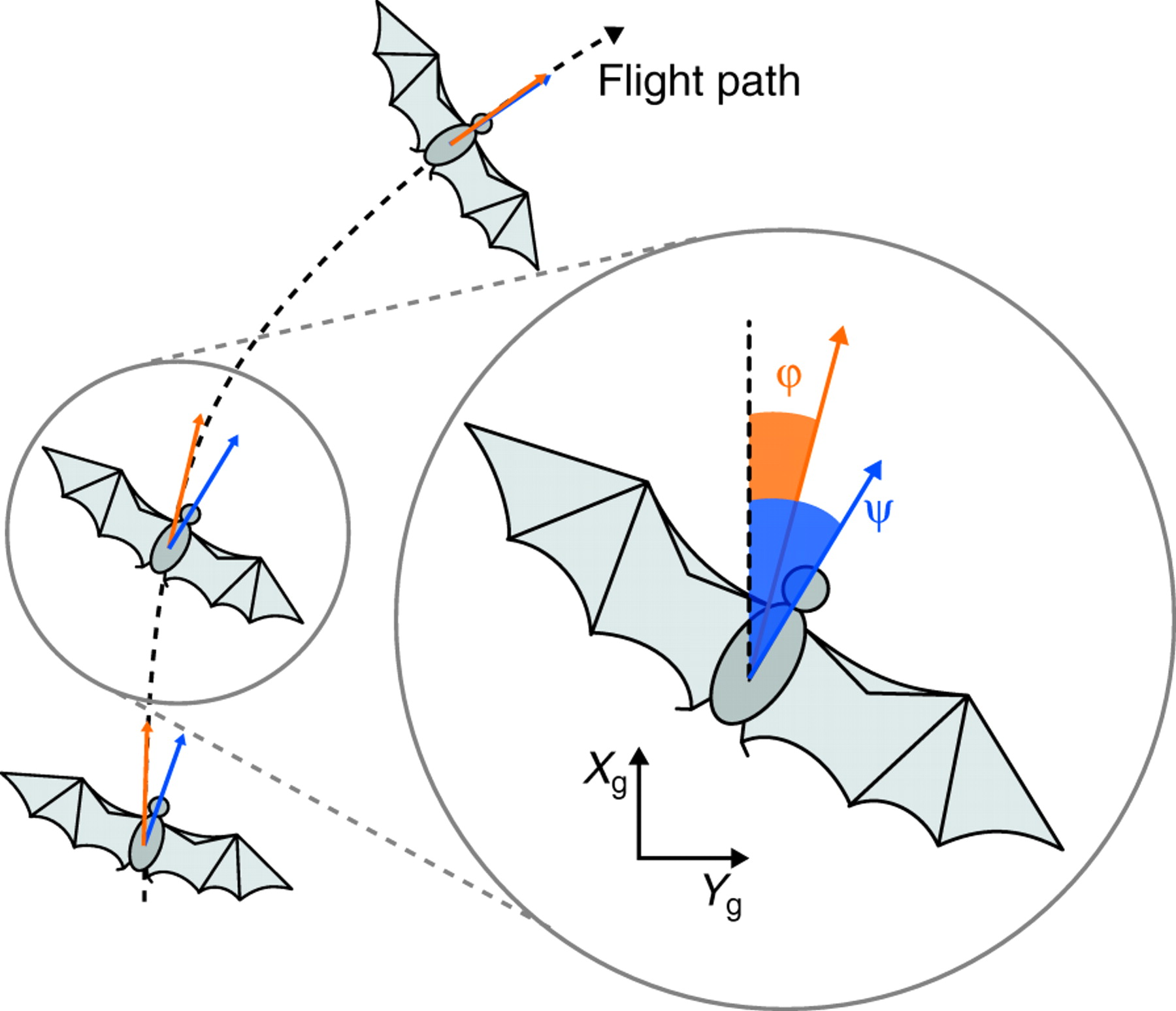

1B. Flight

Bats are mammals with powered flight!

The body structure of bats enable them to fly great distances. Bats have modified skeletons and use various muscles for flight. They do not have reinforced sternums, unlike birds which power their flights with their breast muscles. Also unlike feathers on bird, bats have highly articulated and flexible wings which enable them to fly with greater manoeuvrability, increased lift and lesser drag.

|

Back to top

1. Ecology | 2. Description | 3. Distribution & Habitat | 4. Importance of bats around the world | 5. Conservation | 6. Taxonomy | 7. References |

1C. Diet

Lesser dog-faced fruit bat are fruigivores!

Do you know what is a fruigivore?

|

As a frugivore, the lesser dog-faced fruit bat usually eats fruits, figs, nectar and pollen from flowers. Leaves are high in protein while fruits are high in energy content to allow it to fly through the air. As it has a tiny mouth, smaller fruits are swallowed while larger fruits are chewed. Sometimes it will just drink the juice after chewing and spit out the dehydrated pulp. |

|

|

||||

Matico (Piper aduncum)

|

Tiup tiup (Adinandra dumosa)

|

In Malaysia, the keystone resources to sustain the population of bats are Ficus spp, Piper aduncum and Pternandra echinata. Seasonal feeding is also present for the lesser dog-faced fruit bats in Malaysia. It feeds mainly on fruits in months of March to June, which coincides with local fruiting seasons. On the remaining parts of the year, it feeds on floral parts.

In Singapore, it usually feeds on tiup tiup (Adinandra dumosa) in the secondary forest.

Back to top

1. Ecology | 2. Description | 3. Distribution & Habitat | 4. Importance of bats around the world | 5. Conservation | 6. Taxonomy | 7. References |

1D. Reproduction

The lesser dog-faced fruit bat is polygynous, meaning that one male mates with more than one female partner. Similar to humans, both the male and female take care of their young. Females will reach sexual maturation at about 6 to 8 months, while males mature sexually later at about one-year old. The gestation period lasts approximately 14 to 16 weeks, after which nursing of young takes a surprisingly short 6 to 8 weeks. Mammals such as humans have gestation period of about 38 to 42 weeks, after which nursing of young takes years typically ranging from 16 to 21 years depending on culture.Usually there is only one offspring per litter, with average of two litters per year. However, the mating season is dependent on location.

Different species of bats have different baculum structures!

The bone of the reproductive organ of male bats, namely baculum, can be used to determine different species of bats. In this instance, the lesser dog-faced fruit bat has a triangular shaped baculum located in glans dorsal to urethra (Krutzsch 1959).

Back to top

1. Ecology | 2. Description | 3. Distribution & Habitat | 4. Importance of bats around the world | 5. Conservation | 6. Taxonomy | 7. References |

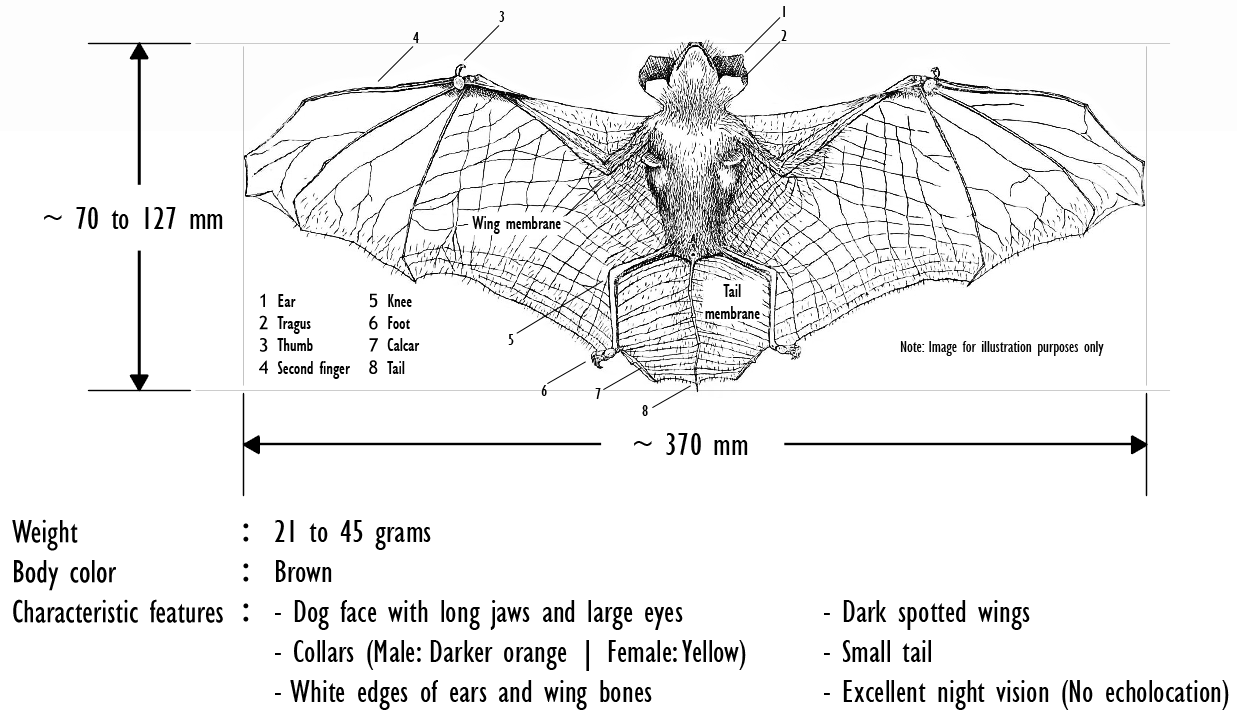

2. Description

The Cynopterus brachyotis is the most common fruit bat to be found in Singapore. It belongs to the Megachiroptera suborder which are frugivores with long heads, long jaws, and large eyes for excellent vision. As a result, they do not require to use echolocation for navigation in the twilight and in caves.

|

Although Megachiroptera refers to megabats, they are not necessarily huge in size and can range from as small as 6 cm to as large as having a wingspan of 1.7m and weighing up to 1.6kg. Of the Megachiroptera, the lesser dog-faced fruit bat is considered relatively small. |

Interestingly, it has a lifespan of 20 to 30 years albeit possessing high basal metabolism rates, similar to other frugivorous species (McNab, 1989).

Back to top

Can you guess which one is the lesser dog-faced fruit bat?

|

|

|

||||||

| BAT [A] |

BAT [B] |

BAT [C] |

||||||

|

|

|

That's right! Bat [A] is the lesser dog-faced fruit bat.

Bat [A] : Lesser Dog-faced Fruit Bat, Cynopterus brachyotis

Bat [B] : Black Flying Fox, Pteropus alecto

Bat [C] : Spectacled Flying Fox, Pteropis conspicillatus

Back to top

How to know which one is the lesser dog-faced fruit bat?

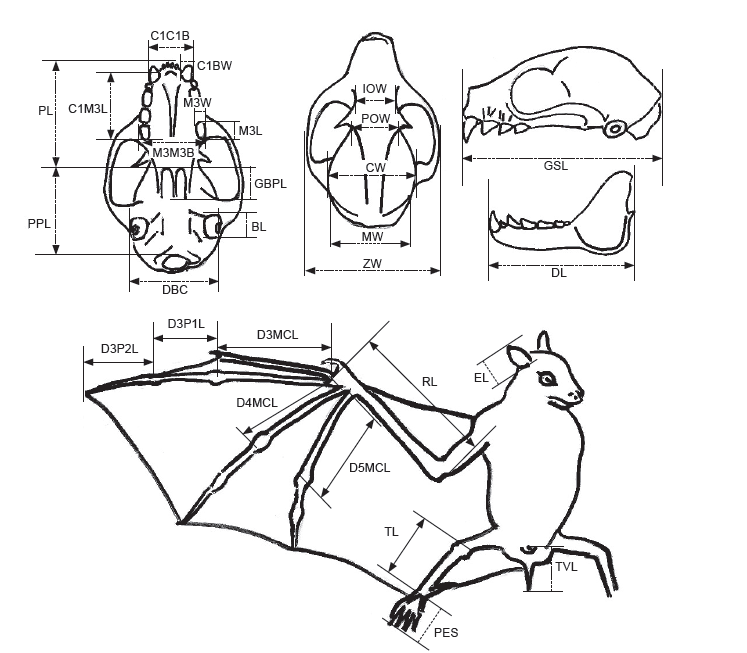

Lesser dog-faced fruit bats typically mature between 70 to 127 millimetres for head and body, with an average wingspan of about 370 millimetres and average wing area of 21 cm2 (Hodgkison et al, 2004). At such a small size, it weighs only about 21 to 45 grams. The greyish young will develop into brown adults with collars, where the males have darker orange collars and the females have yellow collars. You can see that it gets its name from the characteristic long dog face and jaw which is obvious in the pictures below! Other features include dark spotted wings, white edges of ears and wing bones, long forearms of 55 to 92 millimetres, a small tail of about 6 to 15 millimetres and of course, large eyes.

|

|

||||

| Juvenile Fur colour: Grey Collar: No distinct collar |

Adult Fur colour: Brown Collar: Females have yellow collars while males have dark orange collars |

Back to top

|

|

|

In the picture at the middle showing the underside of the skull, the long dog face is because of the elongated bony palate which forms the top of the mouth.

In the picture on the right, you can see the flat quadrate teeth adapted for biting through hard fruit skins and crushing fruits to bits.

Back to top

1. Ecology | 2. Description | 3. Distribution & Habitat | 4. Importance of bats around the world | 5. Conservation | 6. Taxonomy | 7. References |

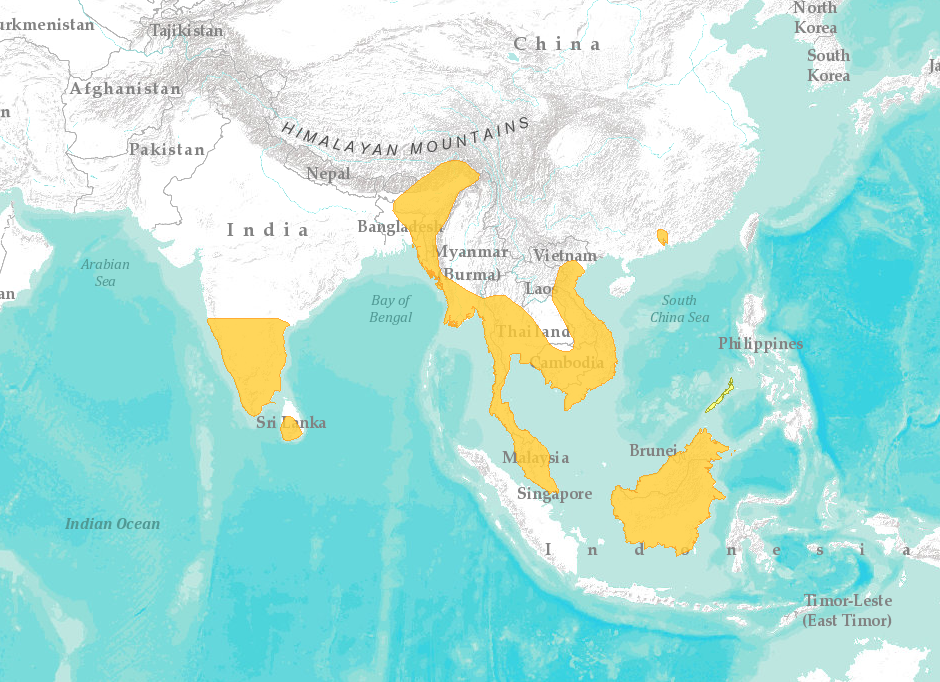

3. Distribution & Habitat

|

|

||||

|

|||||

- Southwest and Northeast India

- Bangladesh

- Andaman and Nicobar Islands

- Southern China

- Indochina

- Sourthern Burma

- Sri Lanka

- Thailand

- Malay Peninsula

- Sumatra

- Java

- Bali

- Sulawesi

- Philippines

- Lesser Sundal Islands

- Kangean islands

- Borneo

- Sulawesi

- Singapore

Back to top

|

|

In Singapore, they can be found in a diverse array of landscapes ranging from rural to urban areas.

This includes:

- Coastal areas

- Lowland primary and secondary forests

- Mangroves

- Riversides

- Cultivated areas

- Parks

- Gardens

- Built-up environments

- Residences

Back to top

3 Tips to Help You Spot Your First Lesser Dog-faced Fruit Bat

|

| Crescent moon. Image from Creative Commons. |

When is the best time?

- Lesser dog-faced fruit bats are more active in the early part of the night and so will be more easily spotted at that time

- In particular, it will be easier to spot it during the period when the moon is waxing from crescent to full moon. This is because there is sufficient moonlight for the bat’s vision and for your vision to spot the bat; the moon also rises above the horizon earlier during this period and this coincides with bat’s more active time.

How to know a lesser dog-faced fruit bat is nearby?

- Fruit cores, droppings, pellets around fruit trees or palm trees

Where to search for better chances of finding one?

- Nature reserves such as the Central Catchment Nature Reserve (CCNR) or the Sungei Buloh Nature Reserve (SGNR).

Back to top

1. Ecology | 2. Description | 3. Distribution & Habitat | 4. Importance of bats around the world | 5. Conservation | 6. Taxonomy | 7. References |

4. Importance of bats around the world

Fruit bats are important seed dispersers!

The lesser dog-faced fruit bat is an important seed disperser and also a plant pollinator. It is able to retain viable seeds in gut for more than 12 hours, allowing long-distance seed disperser (Shilton et al. 1999). The mode of seed dispersal includes defecating or dropping seeds in flight, dispersing seeds over large areas (Tan et al, 1998). One study showed that this species of bats were able to disperse half of tree's original seed within a range of approximately 20 to 30m (Reiter et al. 2006) .

In Malaysia, the Ficus fistulosa is a key component in the diet of the lesser dog-faced fruit bat. So, the seeds of the Ficus fistulosa are mainly dispersed by the lesser dog-faced fruit bat with high percentage of germination (96 to 100% depending on the condition of seed after feeding) (Hodgkison et al, 2003). Hence there is a mutualistic relationship between the lesser dog-faced fruit bat and the Ficus fistulosa. In Singapore, a similar mutualistic relationship is seen between the lesser dog-faced fruit bat and the tiup tiup (Adinandra dumosa) (Phua et al. 1989).

In general, bats can also serve as indicator species to monitor biodiversity. More information can be obtained here.

Back to top

1. Ecology | 2. Description | 3. Distribution & Habitat | 4. Importance of bats around the world | 5. Conservation | 6. Taxonomy | 7. References |

5. Conservation

The lesser dog-faced fruit bat is categorised as of "least concern" because of its extensive presence in Southeast Asia and India, its ability to thrive in a diverse range of habitats (even in people's houses!) and its presumed large population. Also, its population numbers are not declining rapidly enough to qualify as being threatened. The slow decline in population numbers is primarily due to habitat loss from deforestation for timber and oil palm plantations. Even worse, conservation efforts for the lesser dog-faced fruit bat is poor as it is often seen as crop pests due to damage to fruit crops.

However, there are conservation programmes present for fruit bats around the world. They include scientific and charitable groups which help for bat monitoring, and local educational programmes. One example is bat cloud.

Back to top

1. Ecology | 2. Description | 3. Distribution & Habitat | 4. Importance of bats around the world | 5. Conservation | 6. Taxonomy | 7. References |

6. Taxonomy

6A. Type Specimen

Definition of Type specimen: A type specimen is a physical specimen in which the scientific name of every taxon is based on.The type specimen for this species is collected in Dewei river in Borneo, and described by Muller in 1938. However, the current location of the type specimen is unknown.

Back to top

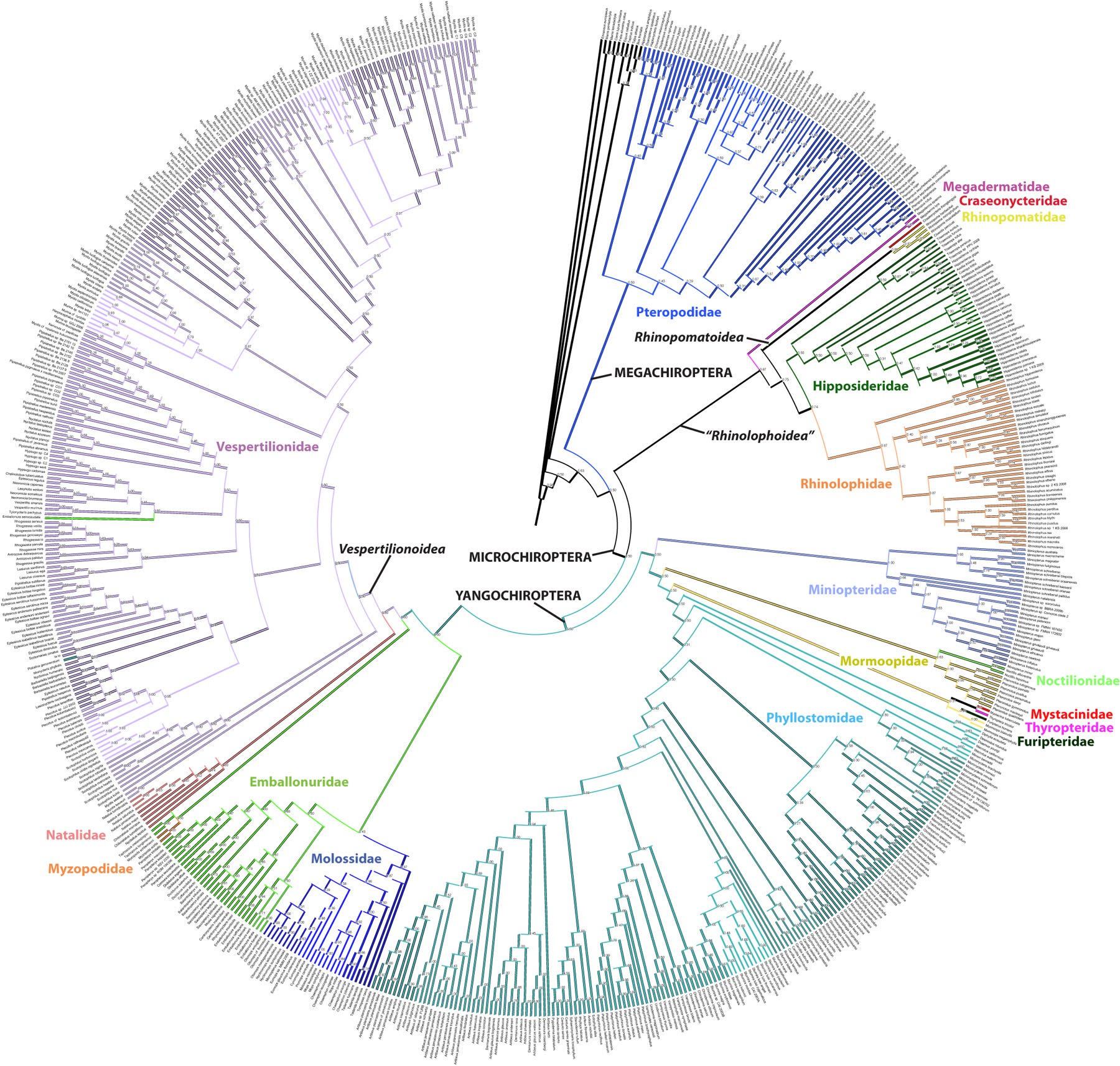

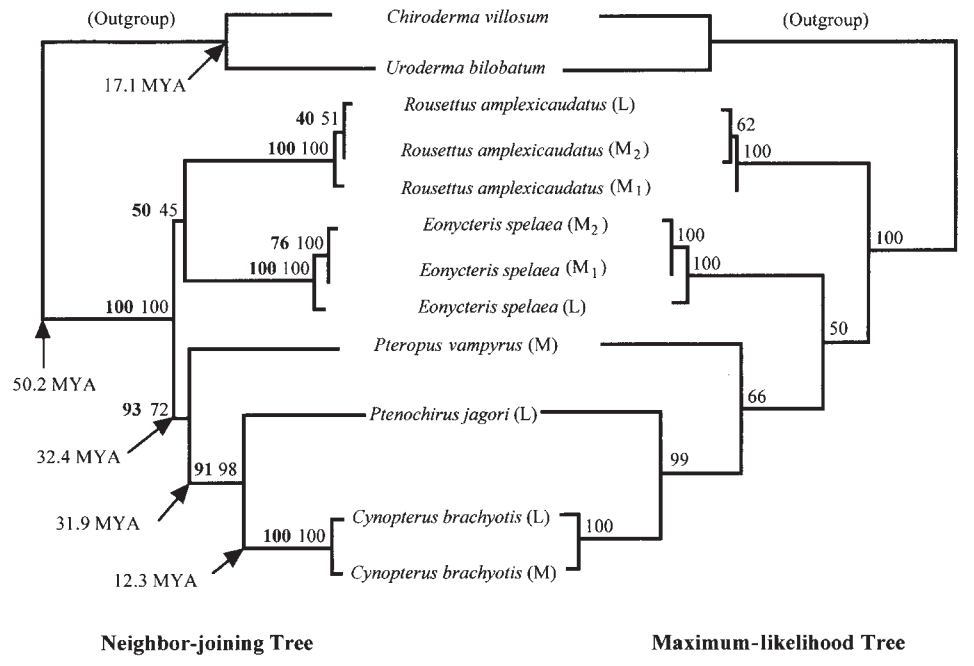

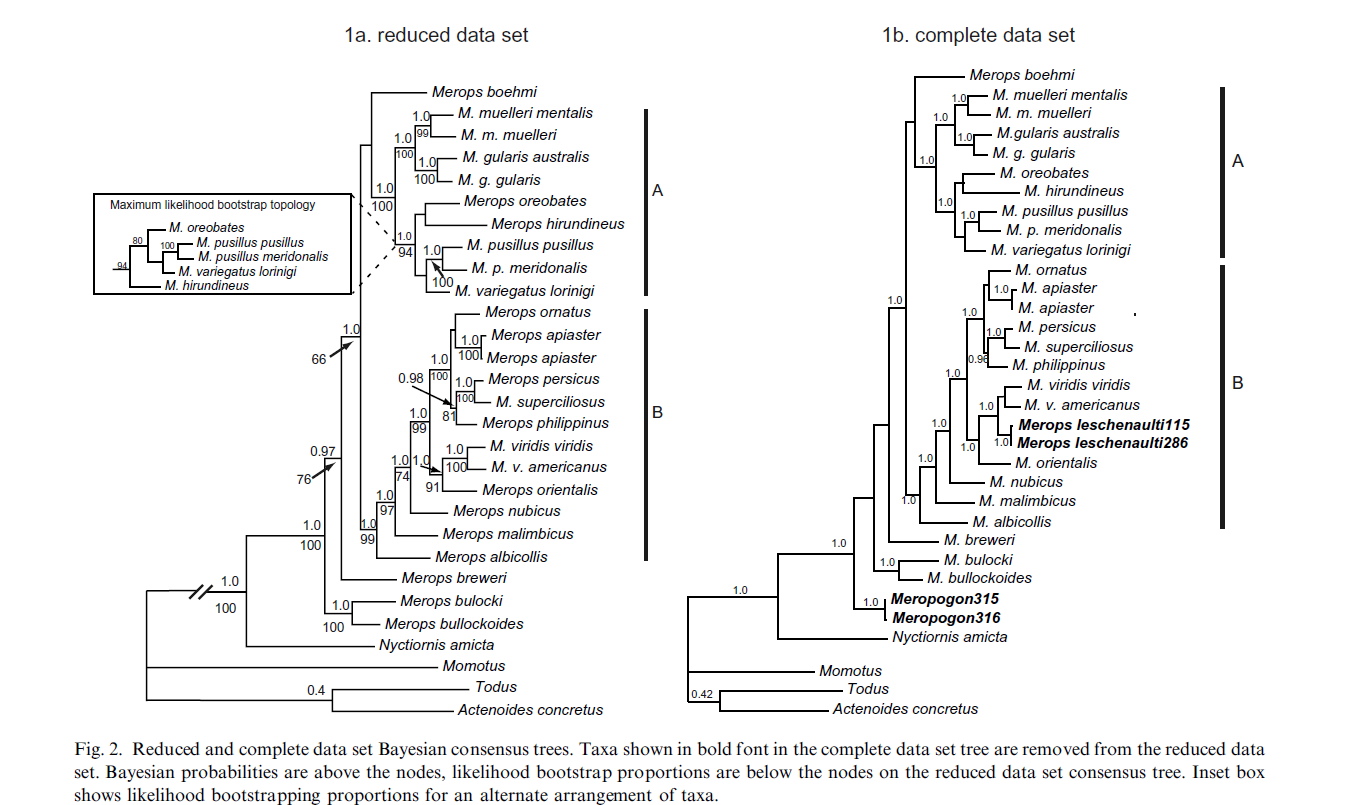

6B. Phylogenetics

Species level phylogeny of bats

Tree of life is constructed using Cytochome b sequences for 648 bats, including 550 named species. This data supports the division of bats into megachiroptera and micrchroptera during evolution. This tree serves to approximate the species level phylogeny of bat Chiroptera until other detailed species level phylogenies are available.

|

| (Bastian et al. 2003) |

Phylogenetic relationships between the species of Megachiroptera are investigated using complete cytochrome b genes sequences, with samples collected from islands of Luzon and Mindanao in Philippines. The phylogenetic tree, generated using both neighbor joining and maximum likelihood methods, shows close evolutionary relationship between Cynopterus brachyotis, Ptenochirus jagori and Pteropus vampyrus.

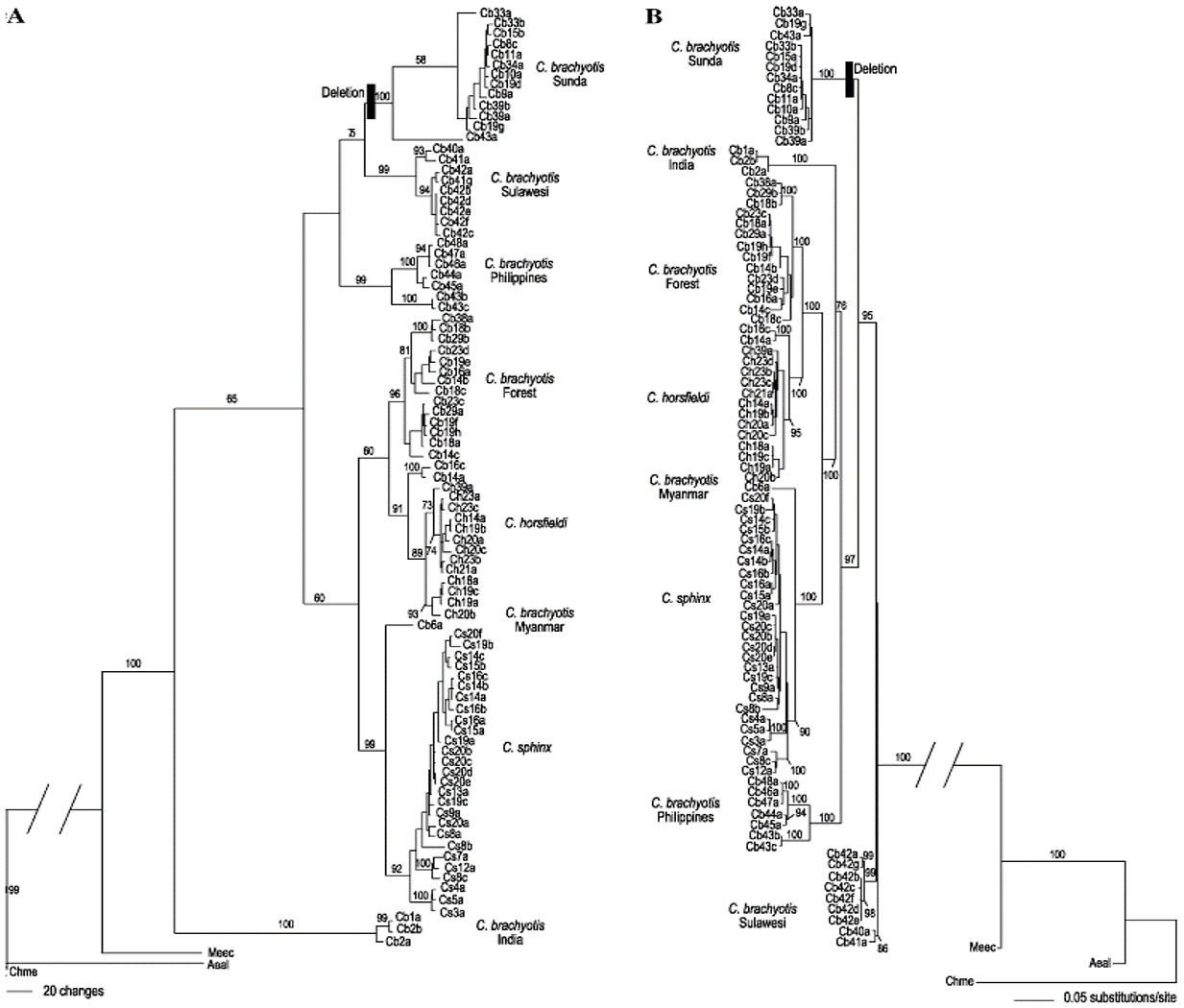

Status of Cynopterus brachyotis as a single species

The current state of Cynopterus brachyotis is uncertain due to variations of bats, namely in size and colour, that is present in the species.

|

| (Campbell et al. 2004) |

Research by (Campbell et al. 2004) has shown that Cynopterus brachyotis comprises of a complex of distinct lineages. In the figure above, two alternative phylogenetic hypothesis has been constructed using cytochome b. Although the position on the tree and the evolutionary relationships within the clades differ significantly, 6 distinct lineages within this species has been shown clearly and they are named according to their place of origin as follows: Forest, Sunda, India, Myanmar,Sulawesi and Philippines. In addition, C. sphinx and C. horsfieldi also formed monophyletic groups within C. brachyotis species complex.

Four lineages from India, Myanmar, Sulawesi and Philippines are well defined geographically. However, two lineages in Malaysia, Sunda and Forest are sympatric and ecologically distinct. Hence, these two lineages are thus further investigated.

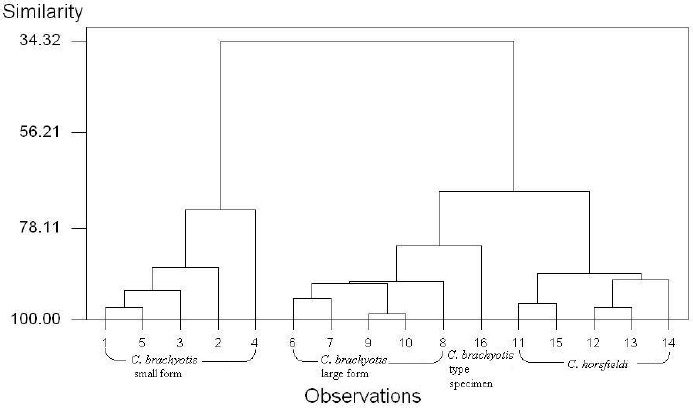

|

| (Abdullah et al. 2006) |

Another research has also shown that there are different morphological forms in Cynopterus brachyotis in Kubah National Park in Malaysia. The morphological measurements used as character states include ear length, tail length, body length and wing span. Using UPGMA cluster analysis on these morphological features, the figure above shows that the small form and large form of Cynopterus brachyotis lies in two distinct clades. Cynopterus brachyotis belonging to the large form clade in the Sunda lineage is found in open areas, orchards and argicultural areas while the smaller form in the Forest lineage is confined in closed habitat or primary forest.

In addition, the type specimen of Cynopterus brachyotis is clustered together with the large form of Cynopterus brachyotis.

In support of this findings, micro-satellite data also showed the presence of two lineages in Southern Thailand, Malaysia and Borneo (Fong PH. 2011).

|

| (Jayaraj et al. 2012) |

|

| Morphological measurements(Jayaraj et al. 2012) |

Another model was also done to differentiate the fruit bats of C. horsfieldii, Sunda and Forest lineages in Malaysia. As the forearm length is usually employed to distinguish these two lineages during field studies, it will not have high accuracy due to variations in forearm length measurements. Thus, this study (Jayaraj et al. 2012) tried to develop a list of features to attempt to classify the lineages for both field studies and museum specimens. These features include skull, dental and external measurements. UGPMA cluster analysis of 28 characters on morphological measurements showed separate clades of C. horsfieldii, C.cf.brachyotis Forest and Cynopterus brachyotis.

In conclusion, more research has to be done to further identify and correctly separate the lineages within Cynopterus brachyotis species. Conservation has to be planned to ensure that all six form do not go extinct. The two lineages Indian and Forest are restricted within the forest habitat, which is becoming increasingly fragmented due to forest loss, thus having higher risks of being endangered.

6C. Gene Sequence

There are 25 barcode sequences of Cynopterus brachyotis from BOLD and GenBank. Example of these sequences include COX1 and cytochrome B. More information can be obtained here.

Back to top

1. Ecology | 2. Description | 3. Distribution & Habitat | 4. Importance of bats around the world | 5. Conservation | 6. Taxonomy | 7. References |

Thank for reading my page! Have a nice day!

Are you still interested in learning more about bats?

Learn more about Bats and Biodiversity here!

Back to top

1. Ecology | 2. Description | 3. Distribution & Habitat | 4. Importance of bats around the world | 5. Conservation | 6. Taxonomy | 7. References |

7. References

Abdullah MT, Jayarajand VK and Abdullah M.T. Preliminary investigation on the validation of Small and Large Forms of Cynopterus brachyotis in Malaysia. Sarawak Museum Journal 62: 223-236.

Bastian T. Severo, Jr., Kazuaki Tanaka, Rea Victoria P. Anunciado, Nelson G. Natural, Augusto C. Sumalde, and Takao Namikawa. 2003. Phylogenetic relationships among megachiropteran species from the two major islands of the Philippines, deduced from DNA sequences of the cytochrome b gene. Can. J. Zool. 79: 1671 - 1677.

Brian K. McNab. 1989. Temperature Regulation and Rate of Metabolism in Three Bornean Bats. Journal of Mammalogy. Vol. 70, No. 1. pp. 153-161

Campbell P, Schneider CJ, Adnan AM, Zubaid A, Kunz TH. 2004. Phylogeny and phylogeography of Old World fruit bats in Cynopterus brachyotis complex. Mol Phylogenetic Evolution 33 (3): 764 - 781.

Gloriana Chaverri and Thomas H. Kunz. 2006. Roosting Ecology of the Tent-Roosting Bat Artibeus watsoni (Chiroptera: Phyllostomidae) in Southwestern Costa Rica. Biotropica. Vol. 38, No. 1. pp. 77-84

Heffner R. S, Koay G., Heffner H. E. 2008. Sound localization Acuity and its Relation to Vision in large and Small Fruit-eating bats: Non-ecolocating species, Eidolon helvum and Cynopterus brachyotis. Hear Res. 241 (1-2): 80 - 86.

Hodgkison Robert, Balding Sharon T. , Akbar Zubaid and Thomas H. Kunz. 2004. Habitat Structure, Wing Morphology, and the Vertical Stratification of Malaysian Fruit Bats (Megachiroptera: Pteropodidae). Journal of Tropical Ecology , Vol. 20, No. 6. pp. 667-673

J. Reiter, E. Curio, B. Tacud, H. Urbina and F. Geronimo. 2006. Tracking Bat-Dispersed Seeds Using Fluorescent Pigment. Biotropica , Vol. 38, No. 1. pp. 64-68

Jayaraj V.K., Charlie J. Laman and Mohd T. Abdullah. 2012. A Predictive Model to Differentiate the Fruit Bats Cynopterus brachyotis and C. cf. brachyotis Forests from Malaysia using Multivariate Analysis. Zoological Studies 51 (2): 259 - 271.

Philip H. Krutzsch. 1959. Variation in the Os Penis of Tropical Fruit Bats. Journal of Mammalogy , Vol. 40, No. 3 (Aug., 1959), pp. 387-392

Phua, P.B. & Corlett, R.T., 1989. Seed Dispersal by the Lesser Short-nosed Fruit Bat (Cynopterus brachyotis, Pteropodidae, Megachiroptera). Malayan Nature Journal, 42: 251-256.

Robert Hodgkison, Sharon T. Balding, Akbar Zubaid and Thomas H. Kunz. 2003. Fruit Bats (Chiroptera: Pteropodidae) as Seed Dispersers and Pollinators in a Lowland Malaysian Rain Forest. Biotropica , Vol. 35, No. 4. pp. 491-502

Shilton L. A, Altringham J. D, Compton S. G, Whittaker R. J. 1999. Old World fruit bats can be long-distance seed disperser through extended retention of viable seeds in the gut. Proc Biol Sci. 266 (1416): 219.

Tan K. H , A. Zubaid & T.H. Kunz. 1997. Tent construction and socialorganization in Cynopterus brachyotis (Muller) (Chiroptera: Pteropodidae) in Peninsular Malaysia,Journal of Natural History, 31:11, 1605-1621

Tan, K.H., Zubaid, A. and Kunz, T.H. 1998. Food habits of Cynopterus brachyotis in Peninsular Malaysia. Journal of Tropical Ecology, 14: 299 - 307.

Tan K. H, A. Zubaid, T. H. Kunz. 2000. Fruit dispersal by Lesser Dog-faced Fruit Bat. Malayan Natural Journal, 54:1, 57-62.