Dugong dugon (Müller, 1776)

Figure 1: A dugong feeding on seagrass

(Photo by Julien Willem, 2008. Source: Wikimedia Commons. Posted under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported)

Table of Contents

1. Overview

The dugong, Dugong dugon, is a herbivorous marine mammal that lives in the shallow water of well-protected coastal areas. They are the only species of the genus Dugong, as well as the only living member of the family Dugongidae. Like other large aquatic animals, dugongs are threatened directly and indirectly by human activities. Their population appears to have shrunk by at least one fifth over the past few centuries, and they have disappeared in some parts of their historic range, mainly due indigenous hunting and the loss of their habitats[1].This page aims to increase public knowledge and interest in dugongs, through the provision of useful and interesting information to anyone who wishes to learn about them. Read on to find out about the general description, habitat, interesting behaviors and many other fascinating facts about these lovely sirens of the sea!

Reading tips:

|

Back to top

2. What’s in a name?

2.1 Common names

The name “dugong” originated from “duyung”, which means “lady of the sea” in Malay[2]. Additionally, the dugong belongs to Order Sirenia, which has its name derived from sirens – the beautiful but dangerous creatures of Greek mythology. How do these animals get such femme-fatale names? Well, it seemed they were actually the source of the mermaid myth! Ancient sailors mistook dugongs and their close relatives manatees for swimming gracefully and suckling their young as beautiful and mysterious women of the sea[3]. Watch a short clip of a dugong swimming and judge for yourself!Video 1: A dugong swimming and emerging on the surface to breathe(Video by National Geographic Television and Film. (Source: Arkive.org. Posted under Terms and Conditions of Use of Materials)

Dugongs are also often called sea cows, as they exclusively feed on seagrass meadows of shallow and sheltered coastal water.

2.2 Scientific name

Dugong was first given the scientific name Trichechus dugon[4] as it was first considered part of the manatees genus Trichechus. It was later renamed to its current scientific name, Dugong dugon, after being assigned into a separate genus by Lacépède in 1799[5].For more information on the taxonomy of dugongs, please visit Taxonomy section.

Back to top

3. How do dugongs look like?

Dugongs have fusiform body shape. An adult usually has a body length between two and four meters, and weighs between 250 to 500 kg[6] [7]. Its thick and smooth skin is pale cream in color at birth, and darkens dorsally and laterally to dark grey with maturity. Sometimes the color might change due to the growth of algae on the dorsal side of the animal[8] .

Dugongs are highly adapted to swimming. They lack hind limbs, but have powerful fluked tails and paddle-shaped flippers to propel and maneuver under water. Additionally, they have short, coarse and sparse hairs on their body, with highest concentration around their mouths (see Figure 3). These hairs are believed to be analogous to the lateral line in fish, and help convey information on water currents and presence of approaching animals and large immobile features of the surrounding[9].

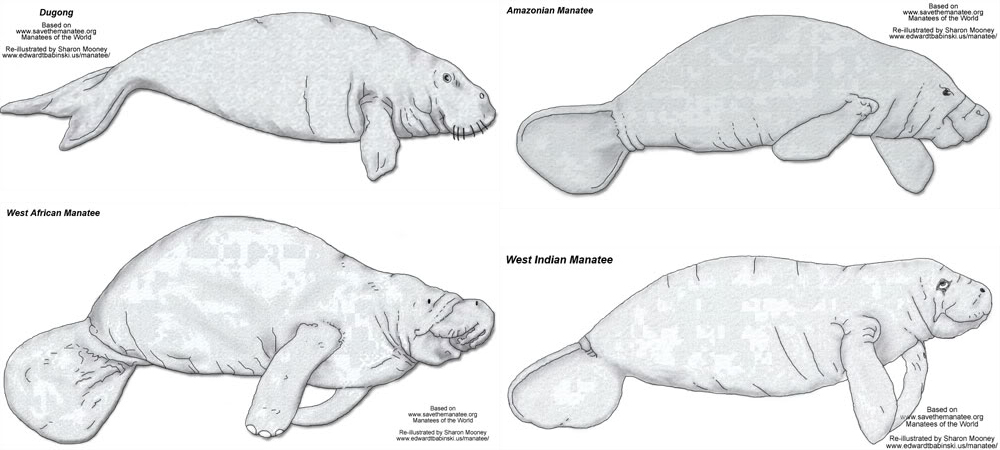

3.1 Dugongs vs. manatees

Figure 4: The four extant species of Order Sirenia (from top left, clockwise): dugong, Amazonian manatee, West African manatee and West Indian manatee(Illustration by Sharon Mooney. Source: etb-whales.blogspot.com. Posted under the website's Terms and Conditions for Use of Public Access Images)

Dugongs and manatees are closely related and thus appear similar to one another. However, they do differ in their morphology and ecology. The most obvious difference that we can observe from Figure 4 is their tail shape: dugong's tail is fork-like while the manatees' are paddle-like. Some other differences are also summed up in Table 1, which could help you determine if that animal you encounter is really a dugong or a manatee.

Table 1: Some morphological and ecological differences between dugongs and manatees[10] [11]

| Features |

Dugongs |

Manatees |

Details |

| Tusk |

Presence in mature male |

Absence |

Order Sirenia (dugong and manatees) is closely related to Order Proboscidea (elephants), but only mature male dugongs have tusks developed from incisors like elephants do. |

| Tail |

Fluke-shaped tail |

Paddle-shaped tail |

This is the best way to differentiate dugongs and manatees. A dugong’s tail has two lobes, called flukes, like those of a whale. |

| Food |

Mainly seagrasses |

A variety of aquatic plants |

If you see a large aquatic mammal feeding on floating hyacinth, mangrove leaves, or other aquatic vegetation that is not seagrasses, chances are it is a manatee! |

| Habitat |

Strictly marine |

Marine or freshwater habitats |

You can never find dugongs in freshwater environment! In contrast, the West Indian and West African manatees can migrate between saltwater and freshwater, and the Amazonian manatee is found exclusively in freshwater habitats. |

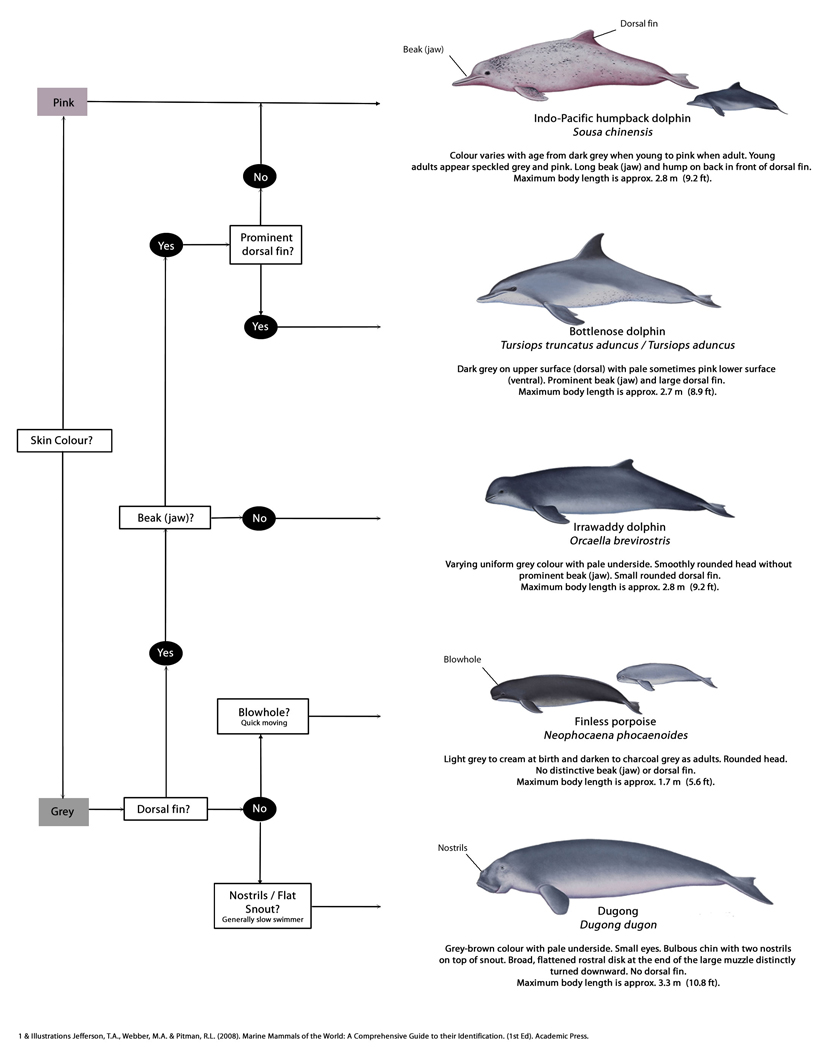

3.2 Dugongs vs. other marine mammals

What if you detect a marine mammal from a great distance and are unable to determine if it is a sirenian in the first place? Figure 5 below shows the Singapore Marine Mammal Identification Chart, which offers you guidance to determine marine mammals that are often found in the coastal areas of Singapore.

Back to top

4. How are dugongs related to other mammals?

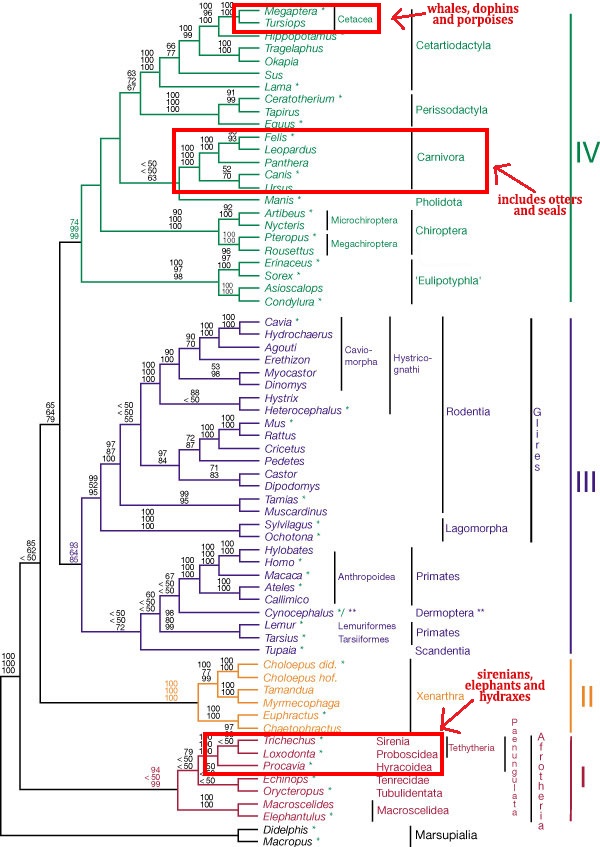

Dugongs belongs to the Mammalia taxon; thus like other mammals, they breathe through their lungs. They cannot breathe underwater and would have to surface for air[12]! As mentioned previously, dugong is the only species of the genus Dugong. Following the extinction of the Stellar’s Sea Cow (Hydrodamalis gigas) in the 18th century, it is now the only extant species of the family Dugongidae.The phylogenetic tree of mammals (Figure 6) shows that dugongs and manatees are not closely related to other aquatic mammals such as whales, dolphins, otters or seals. In fact, their closest extant taxa are Order Proboscidea (the elephants) and Order Hyracoidea (the hydraxes)[13].

Back to top

5. Where can we find dugongs?

5.1 Habitat

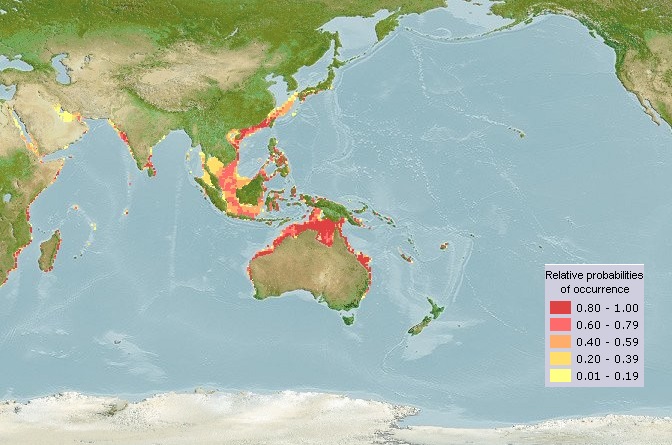

Dugongs strictly live in marine habitats. They are most commonly found in shallow and sheltered coastal waters with large seagrass meadows, such as in bay areas, in lagoons, near mangrove channels and within the waterways between inshore island and the coastline[14]. Furthermore, dugongs could venture into deeper waters in places with wide, shallow and well-protected continental shelf[15].5.2 Geographic range

Dugongs have a wide geographic range which spans at least 48 countries[16]. It includes areas of the Pacific and Indian oceans between 27° north and south of the Equator[17] [18]. Figure 7 shows the native range of dugongs, and the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) also displays the current known range of dugongs in an interactive map, which could be found here.

(Source: AquaMaps. Posted under Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 Unported License)

If you notice carefully, these maps indicate that dugongs are present in Singapore too! For more information regarding dugongs in Singapore, please visit the Dugongs in Singapore section.

Back to top

6. How do dugongs live?

6.1 Feeding

Dugongs are herbivorous and feed predominantly on seagrasses. They seem to prefer species which are high in nitrogen and digestibility, and low in fiber content such as Halophila spp. and Halodule spp.[19] [20] [21].They usually uproot the whole plant; but when it is not possible to do so, they will eat only the leaves. Due to this uprooting behavior, dugongs create distinctive feeding trails[22] as seen in Figure 8.

When seagrass availability is limited, dugongs will feed on marine algae[23] [24]. In subtropical areas, such as Moreton Bay (Brisbane, Australia), shorter days in winter and spring limit the total available nitrogen in seagrasses. Thus, dugongs in these areas increase their nitrogen intake by selectively feeding on some invertebrates such as jellyfish or sea squirts[25].

It also seems that dugongs tend to aggregate in larger and tighter groups when feeding than during any other activities. It is hypothesized that this herding behavior would stimulate the growth of the seagrass species preferred by dugongs, and at the same time, improve the nutritional quality of the seagrasses[26] [27] [28]. Check out a large herd of dugongs feeding by watching Video 2 below!

Video 2: A large herd of dugongs swimming and feeding on seagrasses(Video by BBB Natural History Unit. Source: Arkive.org. Posted under Terms and Conditions of Use of Materials)

6.2 Mating behaviors

Sexual maturity occurs when a dugong is between eight and 18 years old, which is much later than most mammals[29]. Their mating behaviors seem to vary between different populations. In some areas, such as Queensland in the East Coast of Australia, several males were seen to compete for a female through violent fighting. On the other hand, mature male dugongs in Western Australia displayed lekking behaviors as they defended exclusive territories and perform unique actions to attract females[30].6.3 Reproduction

Dugongs have high parental investment during during both gestation and parental care. A female gives birth after a 13 to 15 month gestation, and the litter size is usually one. The calf can start eating seagrasses soon after birth, but will suckle for at least 14 months. Even after this period, the mother will continue to nurse its offspring until it is fully mature[31].Due to their late sexual maturity, low reproductive rate, high parental investment and long generation period, dugongs have very low population growth. In fact, population simulations have shown that the rate of increase most likely would not exceed 5% annually even with low mortality rate[32] [33].

Back to top

7. Why must we protect dugongs?

Dugongs have significant ecological roles in seagrass ecosystems, which in turn are important due to their high rate of primary production and their provision of food, shelter and nursery areas for many aquatic organisms[34]. Seagrass ecosystems’ food webs are largely detritus-based[35]. By eating seagrasses and excreting faecal products, dugongs speed up the conversion of plant materials into nutrients, thus accelerating the nutrient recycling process and increasing efficiency of the entire ecosystem[36].Moreover, dugongs’ intensive and selective grazing on seagrasses encourage the growth of seagrass species that they feed on. Hence, they can influence seagrasses species abundance and distribution in their habitats. This also means that the loss of dugongs in an area can lead to a change in community structure, which in turn might trigger a reduction in the number of commercially valuable fish that uses seagrass meadows as their shelter and nursing ground.

Back to top

8. What are the threats to dugongs?

Currently there is no reliable estimate of the worldwide dugong populations[37]. Existing estimates are likely to be underestimates as they are based on information from either accidental drowning, incidental sightings and spatially and temporally limited survey. Likewise, the population trend for dugong is unknown. However, data from Queensland, Australia has shown that dugong catch rate, which is a major indicator of population size, has decreased by 97% between 1962 and 1999[38]. This suggests that dugong population is on the decline.Currently, dugong is considered as Vulnerable by the IUCN [39], and put under Appendix 1 to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES)[40] .

8.1 Population vulnerability

Dugong population is vulnerable due to their life history. As mentioned in the Reproduction section, dugongs have very low population growth even with the most optimistic birth and mortality rates. Therefore, any slight reduction in adult survivorship due to disease, hunting or habitat loss can cause their population to dwindle.Dugong’s vulnerability is further enhanced by their dependence on seagrasses. Seagrass ecosystems are restricted to coastal areas, which are usually near to human’s settlements. Thus, these ecosystems and their members, including the dugongs, are under high pressure from urbanization, development and economic activities at the coasts[41].

8.2 Current threats

Habitual predation upon adult dugongs by marine animals is not observed[42]. Therefore, the threats to dugong populations are often anthropogenic.8.2.1. Habitat loss and degradation

Seagrasses are very susceptible to damages due to human activities. They can be removed directly by destructive fishing methods like mining and trawling or by vessel movements, as seen in Figure 9. In addition, other coastal activities such as land reclamation or dredging result in an increase in sedimentation, which in turn cause a reduction in light availability. Consequently, seagrasses are smothered or shows a decline in photosynthesis[43]. The species Halophila ovalis, which is one of dugongs' favorite foods, is especially sensitive to light deprivation[44].

Other sources of damage include sewage, heavy metal, desalination brine and other anthropogenic waste products released into the sea. Therefore, the increasing level of agricultural and industrial activities and urbanization processes at coastal areas result in the loss or degradation of seagrass ecosystems, thus putting dugong populations under high pressure.

8.2.2. Indigenous hunting and use

Across their geographic range, dugongs are significant to the indigenous community due to the associated legends and the usage of their meat, oil and other body parts for food, medical treatments, decoration and amulets[45]. Additionally, dugong hunting is considered an expression of identity to the indigenous people of Australia. In some locations, the rate of dugong hunting exceeded 1000 annually in the 1990s[46].

Currently, hunting of dugong is restricted in many countries. Additionally, being put in CITES Appendix 1 mean that any trade of the species across national borders is completely banned. However, dugong products are still highly valued, and thus still seen in the market and in seizure of illegal transactions[47], suggesting that the hunting threat has yet to diminish for dugongs.

8.2.3 Accidental catch and death

Every year, a large number of dugongs are entangled in fish nets or traps and die. However, this number is unquantified[48] [49]. Additionally, vessel strike, which is a major cause of death for manatees in Floria[50], is likely to be a threat to dugong populations in locations with heavy boat traffic.8.2.4. Other threats

Dugongs are potentially threatened by noise and chemical pollutions, but there is a lack of evidence for direct links between these and dugong’s mortality[51].Back to top

9. Dugongs in Singapore

9.1 Locations

Singapore is a well-shetered tropical island, where seagrasses were still common until the mid-20th century[52] . Thus, it could be considered a suitable habitat for the dugongs. Indeed, they have been observed in Singapore water as early as the 1820s, but their occurrence became less frequent as seagrass ecosystems were lost or damaged by coastal activities. They were thought to be nearly extinct in the region by the 1970s until more recent evidence of a viable population emerged[53] [54].Figure 11 shows that recent records of dugong are concentrated around the north-eastern shore of Singapore coast, around Changi, East Coast Park, Pulau Ubin and Pulau Tekong, where seagrass could still be found in small patches or extensive meadows.

9.2 Population size

Unfortunately, quantitative data on dugong distribution and abundance in Peninsular Malaysia and Singapore is unavailable. It is highly possible that dugongs are resident to Johor-Singapore areas, since there exist the largest known seagrass ecosystems in Peninsular Malaysia. However, the increasing pressure from habitat loss and degradation, vessel strikes and indigenous hunting suggest that the local population might be threatened[55].9.3 What can I do?

9.3.1 If you see a dugong in Singapore water

The Singapore Wild Marine Mammal Survey (SWiMMS) is a project ran by the Marine Mammal Research Laboratory (MMRL) in NUS, and funded by the Wildlife Reserves Singapore Conservation Fund (WRSCF). It aims to monitor dugongs, dolphins and porpoises in Singapore waters through a volunteer network and public reporting system.If you spot a dugong, or any marine mammals, you can report your sighting via SMS to 8100 8022 or filling their online sightings form. For more detailed information on the project and reporting methods, please visit their webpage.

9.3.2 If you want to go one step further to protect dugongs

- Join TeamSeagrass to help collecting data for the vast seagrass meadows of Singapore and increasing public interest and awareness in the local seagrass ecosystems!

- Join other volunteer groups to make a difference, not only for the dugongs of Singapore but for our natural environment as well! WildSingapore has a good collection of on-going volunteer activities here, so it is a good place to start!

- Or just share this Dugong species page and other pages in our LSM4254 Wikispaces to spread the word!

Back to top

10. Glossary

Terms are arranged in alphabetical order.| Community |

An assemblage of populations of at least two species living at the same place and time and interacting with one another. Back. |

| Detritus |

The non-living organic debris, usually formed from fecal matter and the bodies, or fragments of bodies, of dead organisms. In a detritus-based food web or ecosystem, the primary source of energy is detritus, which is consumed by detritivores such as earthworms, dung flies or millipedes in terrestrial environment or some crabs, sea stars or sea cucumbers in aquatic ecosystems. Back. |

| Dorsally |

Towards the back of an animal. Back. |

| Ecology |

(the study of) The interaction between organisms, and between them and the physical environment. Back. |

| Geographic range |

The geographical limit within which a species can be found. It can include both the native range, which is where the species historically lived, and the range where it recently established itself at. Also known as distribution. See also: Habitat. Back. |

| Gestation |

The period of time between conception and birth. Back. |

| Habitat |

The environment where a species, or groups of organisms, live naturally. A habitat consists of both the abiotic (i.e. physical, non-living) factors such as water availability, light availability, soil type, temperature, etc., and the biotic (i.e. living) factors such as the presence of food, predators and competitors. See also: Geographic range. Back. |

| Lateral line |

The system of sensory organs that allows fish to detect movement, vibration and changes in pressure in surrounding water. Back. |

| Laterally |

Towards the sides of an animal. Back. |

| Lek |

A group of male individuals of a species that assembles before or during breeding seasons and engage in competitive displays in order to attract females. Back. |

| Morphology |

(the study of) The form and structure of organisms and their body parts. Back. |

| Nutrient recycling |

The flow of elements, such as carbon, and compounds, such as water, between the physical environment and the living organisms. Also known as nutrient cycling, ecological recycling or biogeochemical recycling. Back. |

| Phylogenetics |

(the study of) The evolutionary relationship between organisms (or groups of organisms), based on their morphological features and molecular information. See also: Phylogenetic tree. Back. |

| Phylogenetic tree |

A branching diagram showing the evolutionary relationships between organisms (or groups of organisms). Each internal node, which is a where a branch splits, indicates the most recent common ancestor of the descendants. The closer two groups of organisms are on the tree, compared to other groups, the more closely related these two groups are in term of evolutionary history. See also: Phylogenetics. Back. |

| Primary production |

The synthesis of organic compounds from simple inorganic compounds by living organisms. The most common form of primary production on Earth is photosynthesis, which uses light energy to power the conversion of water and carbon dioxide into sugars and oxygen. Back. |

| Seagrasses |

Unlike what their names and physical appearance might suggest, seagrasses are not grass at all. They are actually flowering plants that are adapted to life in the sea. Back. |

| Sirenia |

A taxonomic group which has a taxonomic rank of Order, and includes aquatic, herbivorous mammals. Currently it includes four extant species: one species of dugong and three species of manatees. See also: Taxon and Taxonomy. Back. |

| Taxon (plural: taxa) |

A taxonomic group consists of species which are closely related based on their evolutionary history. Some taxa are given taxonomic ranks. The most commonly use ranks are superkingdom (or domain), kingdom, phylum (plural: phyla), class, order, family, genus (plural: genera) and species. See also: Taxonomy. Back. |

| Taxonomy |

The science of describing, naming, classifying and identifying all organisms on Earth. Back. |

Back to top

11. Contact me

If you would like to report a corrupted image/video, give a feedback or just want to ask questions related to anything posted on this page, please send an email to meoshikamaru@yahoo.com with the subject "Regarding taxo4254 Wikispaces - Dugong species page".Back to top

12. References

- ^ Lawler, I., Marsh, H., McDonald, B., & Stoks, T. (2002). Dugongs in the Great Barrier Reef. Accessed on 4 November 2014, from http://crcreef.jcu.edu.au/publications/brochures/dugong_2002.pdf

- ^ Kellogg, M. E., 2008. Sirenian conservation genetics and Florida manatee (Trichechus manatus latirostris) cytogenetics. Doctoral dissertation, University of Florida. 160 pp.

- ^ Storer, D. 1984. Mermaid myth stems from dumpy dugong. The Evening Independent, 30 March 1984, pp. 11B.

- ^ Muller, P. L. S., 1776. Des Ritters Carl von Linné Königlich Schwedischen Leibarztes &c. &c. vollständigen Natursystems Supplements- und Register-Band über alle sechs Theile oder Classen des Thierreichs. Mit einer ausführlichen Erklärung. Nebst drey Kupfertafeln.Nürnberg. (Raspe)

- ^ Lacépède, B. D., 1799. Mémoire sur une nouvelle table méthodique des animaux à mamelles. Mémoires de l'Institut National des Sciences et des Arts. Sciences Mathématiques et Physiques, 3: 469-502.

- ^ Heinsohn, G. E., 1972. A study of Dugongs (Dugong dugong) in Northern Queensland, Australia. Biological Conservation, 4(3): 205-213.

- ^ Silas, E. G., 1961. Occurrence of the sea cow, Halicore dugong (erxl.), off the Saurashtra coast. Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society, 58(1): 263-265.

- ^ Jones, S., 1959. On a pair of captive dugongs (Dugong dugon)(Erxleben). Journal of the Marine Biology Association India, 2: 198-202.

- ^ Reep, R. L., C. D. Marshall & M. L. Stoll, 2002. Tactile hairs on the postcranial body in Florida manatees: A mammalian lateral line?. Brain, behavior and evolution, 59(3): 141-154.

- ^ See above [8].

- ^ Husar, S. L., 1978. Dugong dugon. Mammalian Species, 1-7.

- ^ Chilvers, B. L., S. Delean, N. J. Gales, D. K. Holley, I. R. Lawler, H. Marsh & A. R. Preen, 2004. Diving behaviour of dugongs, Dugong dugon. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 304(2): 203-224.

- ^ Murphy, W. J., E. Eizirik, W. E. Johnson, Y. P. Zhang, O. A. Ryder & A. J. O'Brien, 2001. Molecular phylogenetics and the origins of placental mammals. Nature, 409(6820): 614-618.

- ^ Heinsohn, G. E., H. Marsh & P. K. Anderson, 1979. Australian dugong. Oceans, 12(3): 48-52.

- ^ Marsh, H., H. Penrose, C. Eros & J. Hugues, 2002. Dugong Status Report and Action Plans for Countries and Territories. Early Warning and Assessment , United Nations Environment Program UNEP/DEWA/RS.02-1

- ^ Marsh, H., 2008. Dugong dugon. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Accessed on 6 November 2014, from http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/6909/0

- ^ See above [11].

- ^ See above [15].

- ^ Lanyon, J., 1991. The nutritional ecology of the dugong (Dugong dugon) in tropical north Queensland. Doctoral dissertation, Monash University.

- ^ Preen, A., 1995. Impacts of dugong foraging on seagrass habitats: observational and experimental evidence for cultivation grazing. Marine ecology progress series, Oldendorf, 124(1): 201-213.

- ^ Aragones, L. V., 1996. Dugongs and green turtles: grazers in the tropical seagrass ecosystem. Doctoral dissertation, James Cook University of North Queensland.

- ^ See above [20].

- ^ Heinsohn, G. E. & A. V. Spain, 1974. Effects of a tropical cyclone on littoral and sub-littoral biotic communities and on a population of Dugongs (Dugong dugon (Müller)). Biological Conservation, 6(2): 143-152.

- ^ Lipkin, Y., 1975. Food of the Red Sea Dugong (Mammalia: Sirenia) from Sinai.Israel Journal of Zoology, 24(3-4): 81-98.

- ^ Preen, A., 1995. Diet of dugongs: are they omnivores?. Journal of Mammalogy, 163-171.

- ^ See above [19].

- ^ Hodgson, A. J., 2004. Dugong behaviour and responses to human influences. Doctoral dissertation, James Cook University.

- ^ O'Shea, T. J. & J. A. Powell, 2010. Sirenians. In: Steele, J. H., S. A. Thorpe & K. K. Turekian (eds.), Elements of physical oceanography: a derivative of the encyclopedia of ocean sciences. Elsevier, London. Pp. 431-441.

- ^ Anderson, P. K., 1984. Dugong and Manatees. In: Macdonald, D. (ed.), The Encyclopedia of Mammals. New York: Facts on File. Pp. 298–299.

- ^ See above [15].

- ^ See above [15].

- ^ Marsh, H., 1995. The life history, pattern of breeding, and population dynamics of the dugong. Population biology of the Florida manatee, 1: 75-83.

- ^ Marsh, H., 1999. Reproduction in sirenians. Boyd, IL, C. Lockyer and HD Marsh, 243-256.

- ^ Costanza, R., 1992. Ecological economics: the science and management of sustainability. Columbia University Press. 380 pp.

- ^ Peduzzi, P. & G. J. Herndl, 1991. Decomposition and significance of seagrass leaf litter(Cymodocea nodosa) for the microbial food web in coastal waters (Gulf of Trieste, northern Adriatic Sea). Marine ecology progress series, 71(2): 163-174.

- ^ Heinsohn, G. E., J. Wake, H. Marsh, & A. V. Spain,1997. The dugong (Dugong dugon (Müller)) in the seagrass system. Aquaculture, 12(3): 235-248.

- ^ See above [16].

- ^ Marsh, H., G. De'Ath, N. Gribble & B. Lane, 2005. Historical marine population estimates: triggers or targets for conservation? The dugong case study. Ecological Applications, 15(2): 481-492.

- ^ See above [16].

- ^ CITES. (n.d.). Appendices | CITES. Accessed on 3 October 2014, from http://www.cites.org/eng/app/appendices.php

- ^ See above [16].

- ^ See above [11].

- ^ Marsh, H., H. Penrose, & C. Eros, 2003. A future for the dugong? In: Gales, N., M. Hindell & R. Kirkwood (eds.), Marine mammals and humans: fisheries, tourism and management. Melbourne, Australia: CSIRO Publishing. Pp. 383-399.

- ^ Longstaff, B. J., & W. C. Dennison, 1999. Seagrass survival during pulsed turbidity events: the effects of light deprivation on the seagrasses Halodule pinifolia and Halophila ovalis. Aquatic Botany, 65(1): 105-121.

- ^ See above [15].

- ^ See above [39].

- ^ See above [39].

- ^ Perrin, W. F., M. L .L. Dolar & M. N. R. Alava, 1996. Report of the workshop on the biology and conservation of small cetaceans and dugongs of Southeast Asia, Dumaguete, 27-30 June 1995. United Nations Environment Programme, Bangkok.

- ^ See above [15].

- ^ Wright, S. D., B. B. Ackerman,R. K. Bonde, C. A. Beck& D. J. Banowetz, 1995. Analysis of watercraft-related mortality of manatees in Florida, 1979-1991. Population biology of the Florida manatee, 259-268.

- ^ See above [15].

- ^ Chuang, S. H., 1961. On Malayan Shores. Muwu Shosa, Singapore.

- ^ Chew, H. H., 1988. The dugong in Singapore waters. Malayan Naturalist, 22-25.

- ^ Sigurdsson, J. B. & C. M. Yang, 1990. Marine mammals of Singapore.In: Chou, L. M. & P. K. L. Ng (eds.), Essays in zoology. Department of Zoology, National University of Singapore. Pp. 25-37.

- ^ See above [15].