Common name: Jelutong

Table of Contents

Introduction

Jelutong (Dyera costulata) is a native huge forest tree in the Apocynaceae family that can grow up to 60m tall. Found in Southern Thailand, Peninsular Malaysia, Singapore, Sumatra, and Borneo, it was previously valued for its latex as an important ingredient for chewing gum and currently valued for its timber.[1] It is also the species which the Jelutong Tower of Macritchie is named after.Description

| Trunk The trunk is cylindrical and grows up to 60m tall. It is straight and has no buttress roots, but occasionally has a slight swelling at the base.[2] |

Figure 2: Tall and straight trunk of the tree (Photo by Low Xiang Hui)  Figure 3: Base of the trunk having no buttress but with a slight swelling (Photo by Low Xiang Hui) |

| Bark The bark’s colour ranges from reddish-grey or grey to almost black. The surface is smooth to slightly rough with fine, irregular fissures.[2] |

Figure 4: Bark of the tree (Photo by Low Xiang Hui) |

| Leaves The leaves grow in whorls (meaning: radiate from a single point) of 6 to 8, having a dark dull green colour above and glaucous beneath and turns dark brown or black when dried. They are fairly large, with the length of 7 to 18cm, and are oblong-shaped. The new leaves are orange or red in colour during the first few days.[2] |

Figure 5: Leaves growing in whorls (Photo by Wang Luan Keng, permission obtained) Figure 6: Red young leaves of the tree (Image © www.NatureLoveYou.sg) |

| Flowers The tree produces small, star-shaped white or off-white flowers that are about 2mm in size.[2] They usually open between 5-7pm and fall off the next morning between 5-7am.[1] The flowers look like snowflakes when they fall and they cover the ground under the tree like a white carpet. [2] (Click here for an image of the falling flowers) |

Figure 7: Small, white flowers of the tree (Photo by Lee Sui Kei Rachel, permission obtained) |

| Fruits The fruits are made up of woody, brown follicles that grow in pairs. They are usually 20 to 30cm long, up to 4.5cm wide, and are slightly narrowed at both ends. [2] [3] |

Figure 8: Fruit (Photo by Low Xiang Hui) Figure 9: A pair of fruits (Photo by Low Xiang Hui) |

| Seeds The seeds are small, thin, and flat. They are elliptic to oblong in shape and have thin membranous wings at both ends. The seed grain is about 2.5cm long and 1.5cm wide, and 5cm long and 2cm wide with wings included.[2] [3] |

Figure 10: Seed (Photo by Denice H, permission obtained) |

Ecology

The flowers are pollinated by insects.[4] The trees shed their leaves before flowering to increase the visibility of their flowers.[5] The fruits take 2 to 3 months to ripen.[6] Upon ripening, the fruits split open at one side to release the seeds. The seeds are very light and are wind-dispersed.[1]Figure 11: Fruit splitting open at one side (Photo by: Low Xiang Hui)

Human Uses

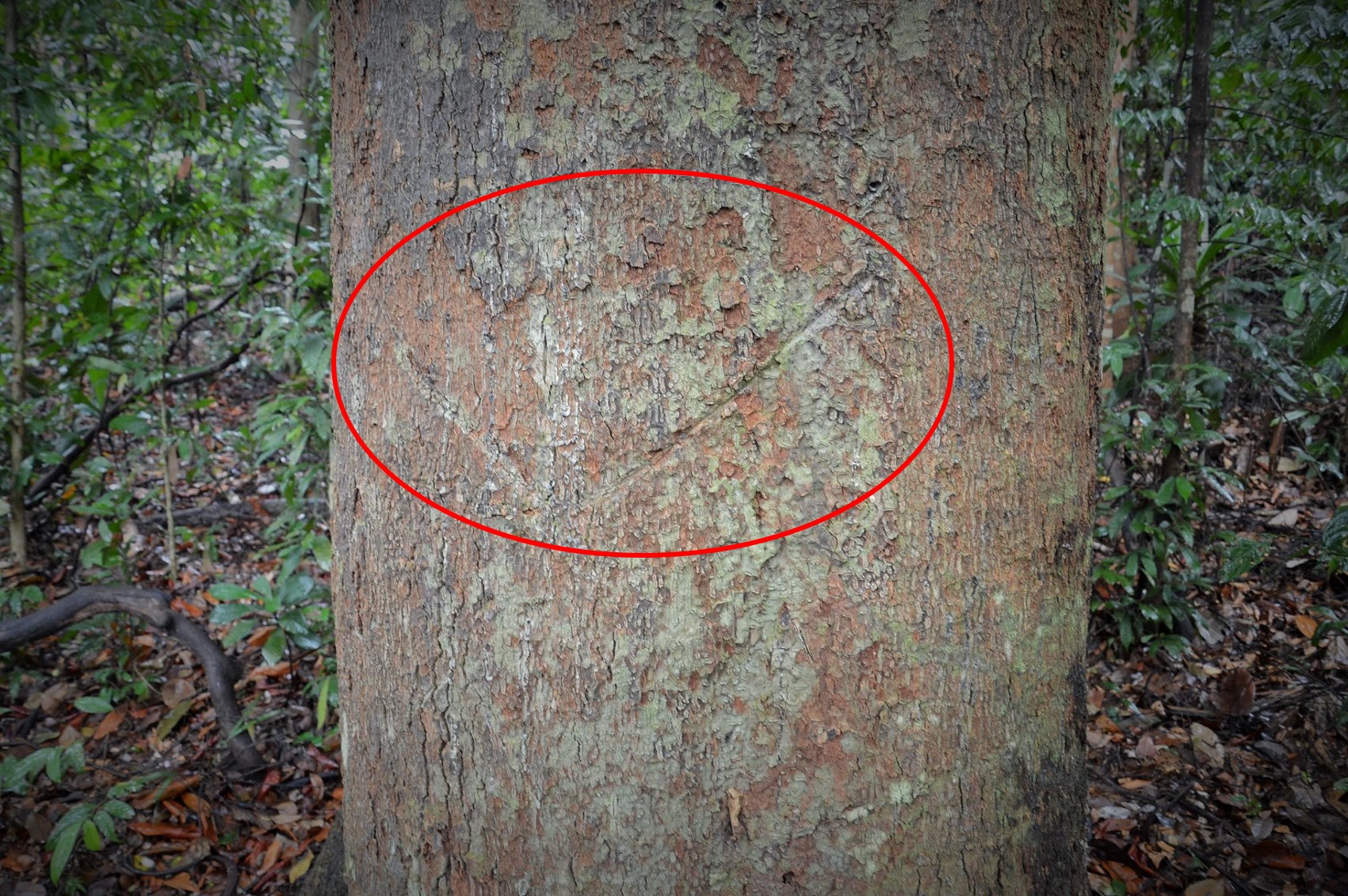

LatexThe tree secretes milky, white latex when cut. The latex was once an important source of rubber before Brazilian rubber trees (Hevea brasiliensis) were introduced and planted in Southeast Asia.[7] The jelutong latex was also formerly used as an important ingredient for chewing gum. Currently, synthetic ingredients are used as a substitute and so its use has greatly decreased. [8]

Figure 12: Slash marks on the tree, indicating that it has been previously tapped for latex (Photo by: Low Xiang Hui)

Figure 13: Latex exuding from the tree (Photo by: Denice H, permission obtained. Annotation by Low Xiang Hui)

Wood

The wood is light, soft, and relatively less durable. Due to its weakness and susceptibility to attacks by termites and beetles, it is not suitable for making products that require strong structures such as furnitures. However, its soft and light properties means it has higher workability. It is therefore used to make products such as pencils, matchsticks, matchboxes, wood carvings, and picture frames.[8]

Potential Uses

PhytoremediationSeveral studies have discovered that this species has the ability to absorb high amounts of heavy metals including zinc, cadmium, nickel, and chromium, in the soil. It is also able to tolerate high concentrations of these heavy metals in the soil. These properties make it a potential species to be planted in contaminated soils to remove heavy metals in the soils.[9] [10] [11]

Reforestation

Jelutong is found to have high photosynthesis and growth rates under high light conditions. Therefore, it can potentially be planted to rehabilitate or reforest a degraded forest, especially at sites where there are large canopy gaps.[12]

Distribution

GlobalThis species can be found in Southern Thailand, Peninsular Malaysia, Singapore, Sumatra, and Borneo. They can be found in both open areas and forests at altitude of up to 1220m.[13]

Figure 14: Distribution of Dyera costulata (Base map from d-maps.com. Annotation by Low Xiang Hui)

Local

They are native in Singapore and can be found in Bukit Timah Nature Reserve, MacRitchie, Nee Soon Swamp Forest, and Singapore Botanic Gardens.[4] [6] Also, there are currently two individuals, situated at Netheravon Road in Changi and Lawn S in Singapore Botanic Gardens respectively, that are listed as Heritage Trees in Singapore.[14]

The tall jelutong tree in Figure 1 and 2 is located at the Petai Trail of Macritchie. The BES Drongos conduct free guided walks on the Trail so those interested can join their walks to learn about the tree and other plants and animals in Macritchie.

Conservation Status

Global status: Lower risk / Least concern[15]Status in Singapore: Common [4]

Taxonomy

Taxonomic Classification

Below is the taxonomic hierarchy of Dyera costulata:[16]| Kingdom |

Plantae |

| Subkingdom |

Viridiplantae |

| Infrakingdom |

Streptophyta |

| Superdivision |

Embryophyta |

| Division |

Tracheophyta |

| Subdivision |

Spermatophytina |

| Class |

Magnoliopsida |

| Superorder |

Asteranae |

| Order |

Gentianales |

| Family |

Apocynaceae |

| Genus |

Dyera Hook f. |

| Species |

Dyera costulata (Miq.) Hook. f. |

Nomenclature

EtymologyThe genus name 'Dyera' is named after Thiselton Dyer, an English botanist and the then Assistant Director of Kew Botanic Gardens, (on Dyera) while 'costulata' is derived from the Latin word costulatus, which means ribbed and possibly refers to the ribbed twigs.(Sabah and Sarawak)

Synonyms

Alstonia grandifolia Miq.; Alstonia eximia Miq.; Dyera laxiflora Hook. f.[17]

Vernacular Names

The name jelutong is used to refer to both Dyera costulata and its closely related species, Dyera polyphylla. Sometimes the term jelutong bukit, or hill jelutong in English, is used to specifically refer to Dyera costulata. On the other hand, Dyera polyphylla is specifically referred to as jelutong paya or swamp jelutong.[8]History

The species was first described from leaves only and was originally known as Alstonia costulata Miq. When Joseph Dalton Hooker was studying the order Apocynaceae, he described a new genus, Dyera, based on the herbarium specimens of two Malayan rubber-producing plants. One of the plants that he based his description on was Alstonia costulata and since then this species has been renamed as Dyera costulata. The genus name Dyera was named after Thiselton Dyer, the then Assistant Director of Kew, who helped Hooker to differentiate rubber-yielding plants catalougued in the Kew Reports. [13]Identification Key

This identification key can be used as an aid for identifying the genera Dyera and the species Dyera costulata (adapted from Tree Flora of Sabah and Sarawak Volume 5 [8] by including only sections relevant to Dyera costulata). To use the key, start by observing the whole plant of interest. Then, choose one of the two descriptions from section 1 of the identification key that fits the plant of interest and look at the corresponding number at the end of that description. After that, follow the number to the subsequent section and repeat the procedure. (For easier reading, the descriptions that fit the genera Dyera and the species Dyera costulata are in bold.)Key to genera

1. Herbs, sometimes with a woody base.........Catharanthus G. Don

Woody plants which are trees, shrubs or climbers.........2

2. Trees or shrubs.........3

Climbers.........19

3. Leaves spirally arranged.........4

Leaves opposite or whorled.........7

7. Leaves whorled.........8

Leaves opposite.........13

8. Shrubs or small trees with little clear latex in cut leaves; anthers with a long appendage.........Nerium L.

Shrubs to large emergent trees with milky latex in the cut leaves; anthers without a long appendage.........9

9. Shrubs with arching stems; flowers trumpet-shaped, more than 5cm long.........Allamanda L.

Trees or shrubs, when young then with erect stems; flowers salver- or platter-shaped, less than 2cm long.........10

10. Intrapetiolar stipules more than 3mm long; large tree; trunk columnar, unbuttressed; leaf margin weakly crenulate or entire; corolla tube much shorter than lobes; fruit a follicle with winged seeds.........Dyera

Key to Dyera species

Tree without pneumatophore roots; leaf apex mostly obtuse to shortly acuminate, rarely rounded; leaf base subcordate to rounded, rarely cuneate, not decurrent onto petiole.........1. Dyera costulata

Tree with pneumatophore roots; leaf apex emarginate, rare rounded or apiculate; leaf base cuneate and decurrent into petiole.........2. Dyera polyphylla

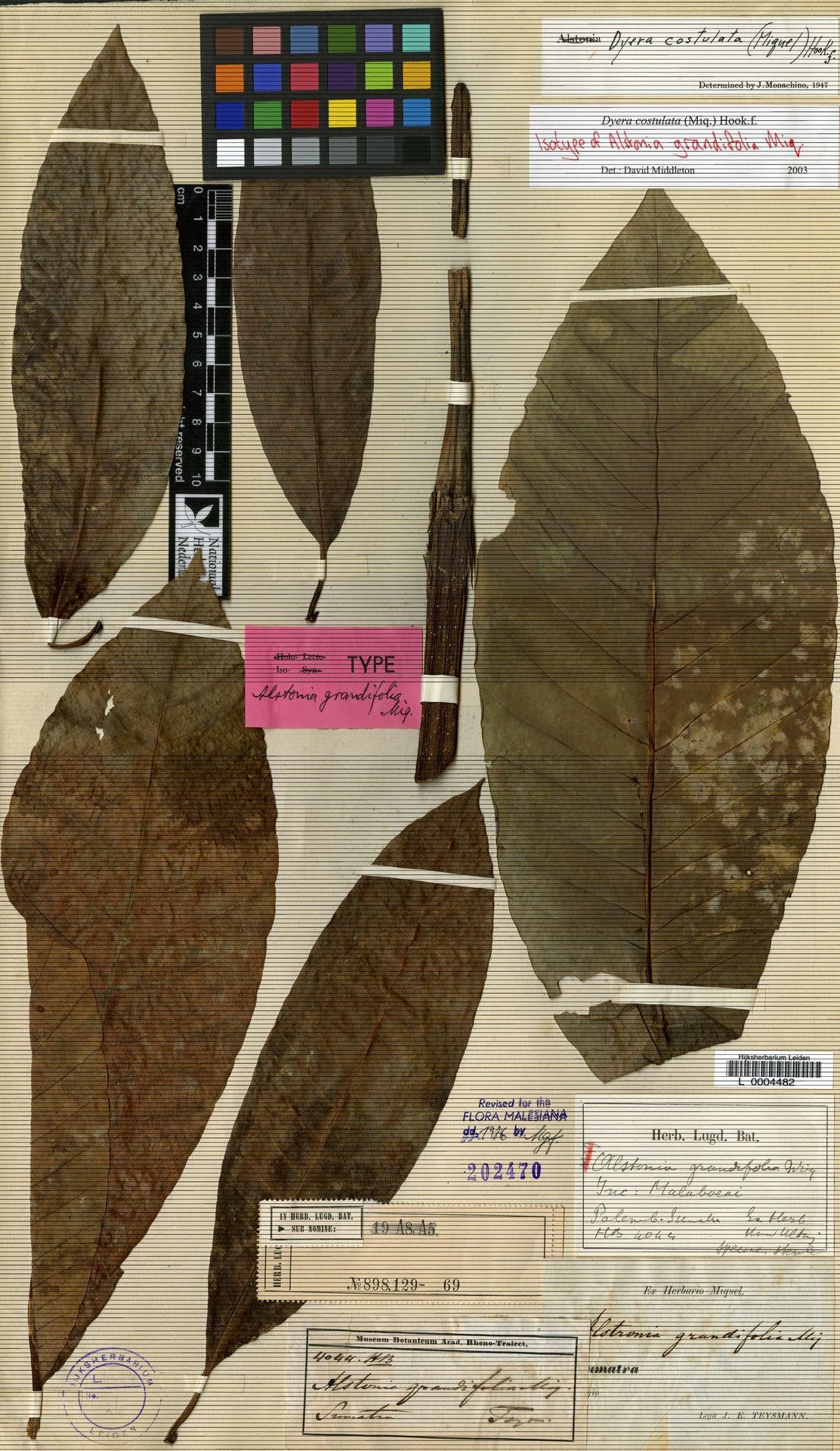

Type Specimen

Dyera costulata's isotype specimen (meaning: one of the multiple specimens from the same gathering as holotype) [18] can be found at the Naturalis Biodiversity Center in the Netherlands (registration number L 0004482). This specimen was collected by Johannes Elias Teijsmann in Sumatra.[19] Reference to this specimen may help to identify the species.

Figure 15: Isotype specimen of Dyera costulata (Image from BioPortal, Naturalis Biodiversity Center under Creative Commons CC0)

Phylogeny

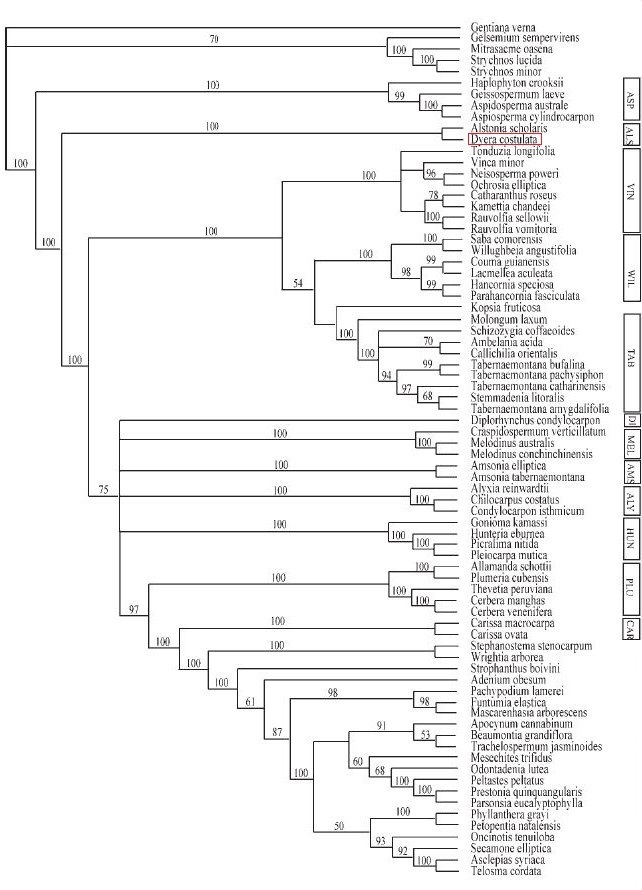

The genera Dyera was previously categorised under the Melodineae clade, being closely related to the genera Craspidospermum and Melodinus.[20] However, a phylogenetic analysis of the subfamily Rauvofioideae in the family Apocynaceae, conducted by Simões et al. (2007) using morphological data and sequences from five DNA regions of the chloroplast genome (matK, rbcL, rpl16 intron, rps16 intron, and 3' trnK intron), showed a different result. The strict consensus of the 28 most parsimonious trees is asfollows.[21]

Figure 16: The strict consensus of the 28 most parsimonious trees of the subfamily Rauvolfioideae generated by combined molecular data from five DNA regions of the chloroplast genome and morphological data, with Dyera costulata annotated with a red box (Image by Simões et al., 2007, permission pending. Annotation by Low Xiang Hui)

Abbreviation: OUT = Outgroup; ASP = Aspidospermeae clade; ALS = Alstonieae clade; VIN = Vinceae clade; WIL = Willughbeieae clade; TAB = Tabernaemontaneae clade; DI = Dyplorhynchus; MEL = Melodineae clade; AMS = Amsonia clade; ALY = Alyxieae clade; HUN = Hunterieae clade; PLU = Plumerieae clade; CAR = Carisseae clade; APSA = Apocynoideae, Periplocoideae, Secamonoideae, and Asclepiadoideae [21]

Based on the tree, Dyera costulata belongs to the Alstonieae clade. This result suggests that Dyera is more closely related to Alstonia compared to Craspidospermum and Melodinus. The Bootstrap value for this clade is 100, indicating that this clade is highly supported. It is suggested that the discrepancy between traditional classification and the phylogenic results in this subfamily is mainly due to morphological homoplasy, especially of the characters of fruit and seed, whereby non-differentiated style-heads, syncarpous ovaries, indehiscent fruits and winged seeds have evolved in parallel multiple times.[21]

Page by: Low Xiang Hui. Please contact me at a0112192@u.nus.edu for any enquiry or clarification.

Images Used

Figure 1, 2, 3, 4, 8, 9, 11, 12: Untitled by Low Xiang Hui. Personal image.Figure 5: "Dyera costulata" by Wang Luan Keng. Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum. URL: http://lkcnhm.nus.edu.sg/dna/organisms/details/339

Figure 6: "DSC05391 (16)" by Kwan. URL: http://www.natureloveyou.sg/Dyera%20costulata/Main.html

Figure 7: Untitled by Lee Sui Kei Rachel. Personal image.

Figure 10, 13: Untitled by Denice H. URL: http://colouredfantasy.blogspot.sg/2012/04/trees-one-day-trip-frim.html

Figure 14: "Southeast Asia: states, names" by d-maps.com. URL: http://www.d-maps.com/carte.php?num_car=5268&lang=en

Figure 15: Naturalis Bioportal. (n.d.). Specimen 0004482. URL: http://data.biodiversitydata.nl/naturalis/specimen/L%20%200004482

Figure 16: Simões, A. O., Livshultz, T., Conti E., & Endress, M. E. (2007). Phylogeny and systematics of the Rauvolfioidae (Apocynaceae) based on molecular and morphological evidence. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden, 94, 268-297

References

- ^ Ng, P., Corlett, R., & Tan, H. (2011). Singapore biodiversity: An encyclopedia of the natural environment and sustainable development. Singapore: Editions Didier Millet in association with Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research.

- ^ Williams, L. (1963). Laticiferous plants of economic importance IV jelutong (Dyera spp.). Economic Botany, 17(2), 110-126.

- ^ Keng, H. & Ling Keng, R. (1990). The concise flora of Singapore: Gymnosperms and dicotyledons (pp. 141-144). Singapore: Singapore University Press.

- ^ NParks. (n.d.). Plant detail - Dyera costulata (Miq.) Hook. f.. Retrieved 9 November 2016, from https://florafaunaweb.nparks.gov.sg/Special-Pages/plant-detail.aspx?id=2866

- ^ Appanah, S. (1990). Plant-pollinator interactions in Malaysian rain forests. In K. S. Bawa & M. Hadley (Eds.), Reproductive Ecology of Tropical Forest Plants (pp. 85-101). Paris: UNESCO.

- ^ Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum. (n.d.). Dyera costulata (Miq.) Hook. f.. Retrieved 9 November 2016, from http://lkcnhm.nus.edu.sg/dna/organisms/details/339

- ^ MacKinnon, K. (1996). The ecology of Kalimantan. Hong Kong: Periplus Editions.

- ^ Middleton, D. J. (2004). Apocynaceae. In E. Soepadmo, L. G. Saw, & R. C. K Chung (Eds.), Tree Flora of Sabah and Sarawak Volume 5 (pp. 1-30). Kuala Lumpur: Forest Research Institute Malaysia.

- ^ Majid, N. M., Islam, M. M., Abdul Rauf, R., Ahmadpour, P., & Abdu, A. (2012). Assessment of heavy metal uptake and translocation in Dyera costulata for phytoremediation of cadmium contaminated soil. Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica, Section B - Soil & Plant Science, 62(3), 245-250.

- ^ Ghafoori, M., Majid, N. M., Islam, M. M., & Luhat, S. (2011). Bioaccumulation of heavy metals by Dyera costulata cultivated in sewage sludge contaminated soil. African Journal Of Biotechnology, 10(52), 10674-10682.

- ^ Majid, N. M., Islam, M. M., & Abdul Rauf, R. (2012). Evaluation of Jelutong (Dyera costulata) as a phytoremediator to uptake copper (Cu) from contaminated soils. Australian Journal of Crop Science, 6(2), 369-374.

- ^ Kenzo, T., Yoneda, R., Matsumoto, Y., Azani, A. M., & Majid, N. M. (2011). Growth and photosynthetic response of four Malaysian indigenous tree species under different light conditions. Journal of Tropical Forest Science, 23(3), 271-281.

- ^ Hooker, J. D. (1882). On Dyera, a new Genus of Rubber-producing Plants belonging to the Natural Order Apocynaceae, from the Malayan Archipelago. Journal of the Linnean Society of London, Botany, 19(121), 291-293.

- ^ NParks. (2016). Heritage Trees. Retrieved 23 November 2016, from https://www.nparks.gov.sg/gardens-parks-and-nature/heritage-trees

- ^ Asian Regional Workshop (Conservation & Sustainable Management of Trees, Viet Nam, August 1996). (1998). Dyera costulata. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 1998: e.T33212A9766586. Retrieved 9 November 2016, from http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.1998.RLTS.T33212A9766586.en.

- ^ ITIS. (n.d.). Dyera costulata (Miq.) Hook. f. - Taxonomic Serial No.: 505986. Retrieved 9 November 2016, from https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=505986#null

- ^ Middleton, D. J. (2003). A revision of Dyera (Apocynaceae: Rauvolfioideae). Gardens' Bulletin Singapore, 55(2003), 209-218.

- ^ McNeill, J., Barrie, F. R., Buck, W. R., Demoulin, V., Greuter, W., Hawksworth, D. L., Herendeen, P.S., Knapp, S., Marhold, K., Prado, J., Prud'homme Van Reine, W. F., Smith, G. F., Wiersema, J. H., & Turland, N. J. (2012). International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (Melbourne Code) Chapter II, Section 2: Typification, Article 8. Retrieved 23 November 2016, from http://www.iapt-taxon.org/nomen/main.php?page=title

- ^ Naturalis Bioportal. (n.d.). Specimen - Dyera costulata (Miq.) Hook. f. - L 0004482. Retrieved 9 November 2016, from http://data.biodiversitydata.nl/naturalis/specimen/L%20%200004482

- ^ Endress, M. E. & Bruyns, P. V. (2000). A revised classification of the Apocynaceae s.l. The Botanical Review, 66(1), 1-56.

- ^ Simões, A. O., Livshultz, T., Conti E., & Endress, M. E. (2007). Phylogeny and systematics of the Rauvolfioidae (Apocynaceae) based on molecular and morphological evidence. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden, 94, 268-297.