Galeopterus variegatus Audebert, 1799

|

| Sunda colugo. Photo by: Alan Yeo |

One of a kind animal!

- Our distant relatives

- Special comb-shaped teeth

- Master gliders

- Unique marsupial-like reproduction

- Fastest digestive system

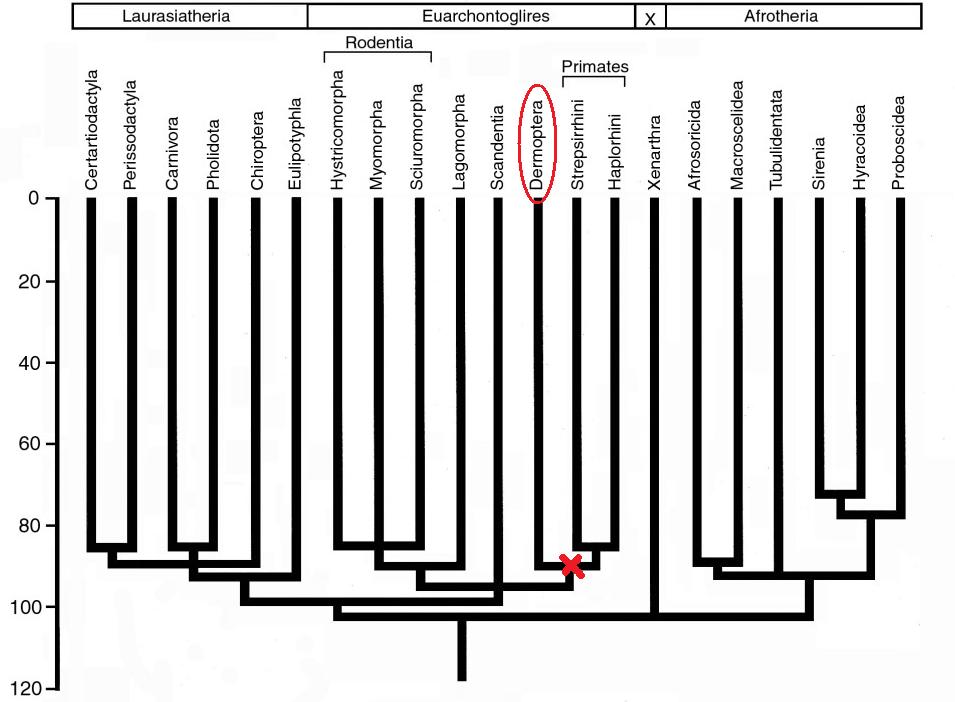

Colugos are also known as ‘flying lemurs’ however, they neither fly nor are they lemurs! Instead they are able to glide from tree to tree. There are currently only two species of Colugos, making the order Dermoptera the smallest of all the 26 mammalian orders. While the colugos cannot be kept in captivity, the Sunda colugos can be found Singapore and the only way to see it is to go on an adventure! Sadly, not a lot is known about these secretive animals.

Singapore? WHERE?

- Central Catchment Area

- Bukit Timah Nature Reserve

- Adjacent areas of mandai forest*

- South of the Pan-Island Expressway (PIE), near Swiss Club Road

Table of Contents

Watch a video!

Name

Colugo gliding. Photo by: Ria Tan

Binomial: Galeopterus variegatus Audebert, 1799*

*It has an older name: Cynocephalus variegatus

Vernacular: Malayan Flying Lemur*, Malayan Colugo, Sunda Flying Lemur, Sunda Colugo

In older literature, some names such as "flying cat", "cobego" or “Kubong” might still turn up.

*The name flying lemur is a misnomer as the Colugo neither flies nor is a lemur.

Etymology

Colugos are classified under the order Dermoptera which in Greek means "skin-wing" (derma refers to "skin" and ptera refers to "wing"). Currently, under this order, there is only one family that is Cynocephalidae which in Greek means "dog-head" (cyno refers to "dog" and cephalus refers to "head").Variegatus is from the Latin term variegare which means "various". This indicates that the Sunda Colugo has a varied fur colour. There are so many different variants that there are 20 subspecies described!

Classification

Order: Dermoptera Familia: Cynocephalidae Genus: GaleopterusKingdom: Animlia

Phylum: Chordata

Subphylum: Vertebrata

Class: Mammalia

Subclass: Theria

Infraclass: Eutheria

Order: Dermoptera

Family: Cynocephalidae

Genus: Cynocephalus

Species: Galeopterus variegatus (Audebert, 1799)

Subspecies

In 1929, Chasen and Kloss examined 125 skins and based on skull, size and colour, they created a classification key for 11 of the 20 known subspecies which are shown below in Table 1 as an abbreviated form (Lim, 2007).Table 1: Subspecies of Galeopterus variegatus

| Name |

Characteristics |

Location |

| Galeopterus variegatus. variegatus |

Largest and darkest form |

Java, Indonesia |

| G. v. termmincki |

Smaller and paler than G. v. variagatus |

Sumatra, Indonesia |

| G. v. peninsulae |

Size liker G. v. termmincki, sexes markedly different in colour |

Malay Peninsula/Penang/Singapore |

| G. v. taylori |

Same size or smaller than G. v. peninsulae, colour different (darker) |

Tioman Island, Malaysia |

| G. v. natunae |

Small |

Bunguran, Natuna, Anamba Island |

| G. v. borneanus |

Also small, colour highly variable |

Borneo and Banguey islands |

| G. v. chombolis |

Like G. v. natunae, but smaller |

Riau Archipelago, Indonesia |

| G. v. pumilus |

Small and pale |

Butang islands, Straits of Malacca |

| G. v. terutaus |

Smaller than G. v. peninsulae |

Terutau and Langkawi islands |

| G. v. perhentianus |

Small, narrow brain-case |

Perhentian islands, Malaysia |

| G. v. aoris |

Small, dark, little rufous |

Pulau Aur, Malaysia |

Diagnosis

How do I know it’s a colugo?

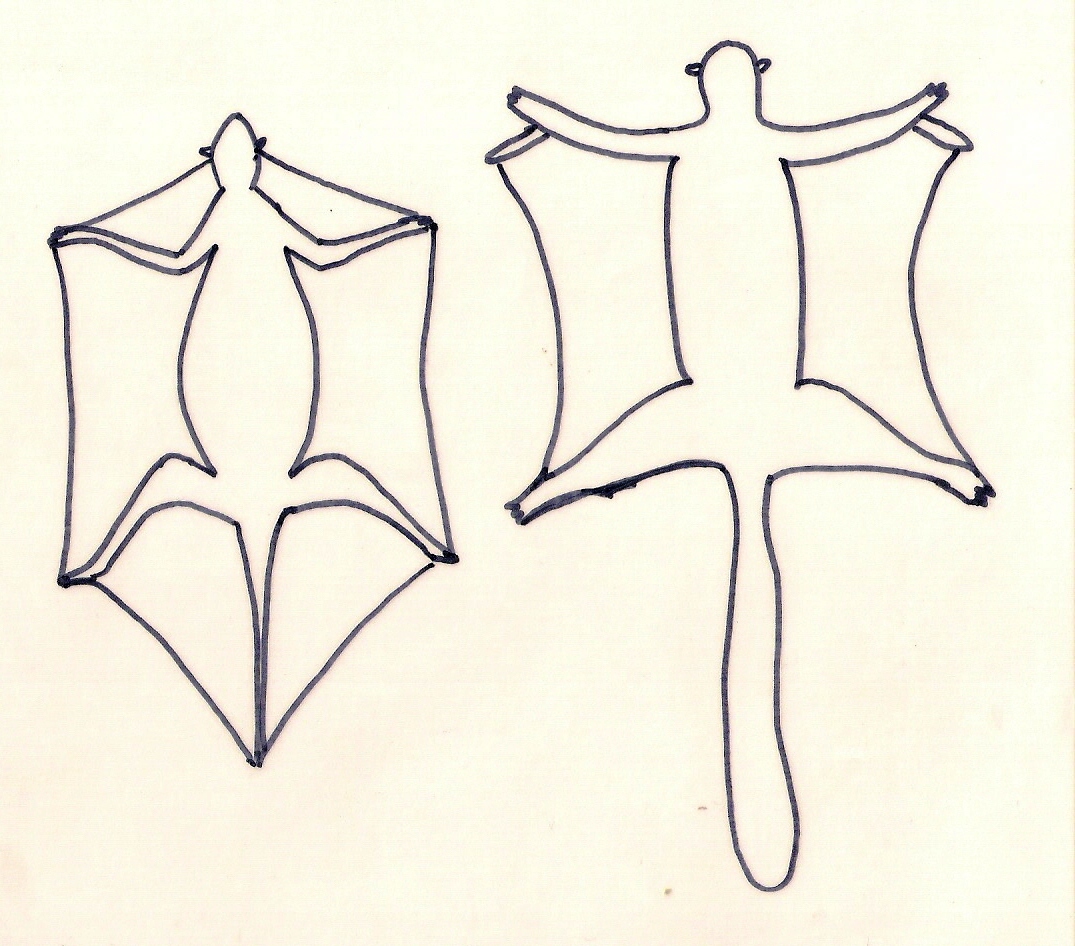

It has a gliding membrane (called the patagium) enclosing all four limbs and tail to its tip.

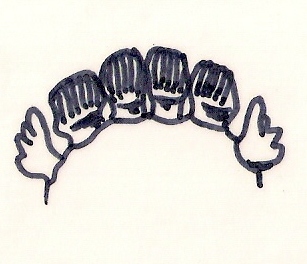

It has a unique tooth structure in which the incisors have two roots and the lower incisors are comb-shaped.

One of a kind comb-shaped lower incisors

|

It is sometimes confused with flying squirrels which differences are compared in Table 2 and the difference in the gliding membrane.

Table 2: The characteristic differences between flying squirrels and colugos

| Differences |

Colugo |

Flying Squirrel |

| Teeth |

Lower incisors are comb-shaped |

Rodent pattern |

| Gliding membrane |

Completely enclosing limbs to the toes and to the tip of the tail. |

Extended to ankle and wrist only. Supported by an extended bone of the wrist. Tail is completely free of an enclosing membrane. |

|

| Comparison of gliding membrane. L: Colugo, R: Flying Squirrel. Sketch by: Ou Yang Xiuling |

Note: While there are only two different species of colugos, Cynocephalus volans (Phillippine Colugo) can only be found in Philippine. It is much smaller compared to the Sunda Colugo and has differences in the craniodental region which might be due to differences in feeding ecology. The Philippine colugo has larger teeth with deeper mandibles and canine-like incisors (Stafford & Szalay, 2000).

Description

Top: Female, Bottom: Male. Male colugos tend to have a richer colour. Photo by: Alan Yeo

Adult

Size: Head and body: 380 mm, Tail: 280 mm, Hindfoot: 65 mm, Skull: 70 mm, Weight: 1 kg (Harrison, 1974)

Color: Body often brownish grey with dorsal irregular paler spots however, fur colour and pattern varies with geographic location.

Head: Small head which is broad and flattened with large forward-facing eyes, small, rounded, almost naked and pinkish in colour ears.

Dentition: Incisors have two roots. Lower incisors look like "finely-toothed combs" (Payne et al., 1985). Dental formula is: (Incisors 2/3, Canines 1/1, Pre-molars 2/2, Molars 3/3) x 2 = 34 (Walker, 1983)

Body: Underside of patagium is hairless and pink.

Feet: Broad; all digits end with sharp and curved claws

Note: Females have a single pair of mammae located near the armpits (Walker, 1983)

|

| Sunda colugo distribution in green. Illustration by: Ou Yang Xiuling |

Where to find them?

Current distribution

- Singapore- Malaysia

- Western Indonesia

- Southern Myanmar

- Southern Thailand

- Indochina*

*Populations are poorly documented and are significantly smaller (about 20%) than the Sunda Colugo. Hence they might be a different species.

Habitat

The Sunda Colugo belongs to the tropical rainforests where there is heavy rainfall year round. They can be found in both primary and secondary forest. Sometimes, they also spread out to nearby plantations (e.g. coconut plantations reported by Tweedie, 1978).Lim, 2007 discussed that while they are found in secondary forests, primary forests are more favourable as there are taller trees which provide a greater three-dimensional space for these arboreal animals. There is also a greater biodiversity of flora for generalist (i.e. it eats a variety) colugos. Moreover, there is a larger number of older trees which are the source of cavities that Colugos use as refuge and rest.

Biology

It is an arboreal animal. It is largely nocturnal but can sometimes be active in the morning and late afternoon (Payne et al., 1985). It is usually seen clinging to the side of a tree trunk, gliding between trees or hanging upside-down from a branch ("looking like a tattered old umbrella" - Harrison, 1974 or "sloth fashion" - Anderson & Jones, 1984). However, very little is known in particular to Sunda Colugos such as its diet, life history and its role in the rainforest (Lim, 2007).Vegetarians

Their natural diet consists of young leaves, leaf shoots and flower buds (Lim, 2007). |

| Colugo feeding on young leaves. Photo by: Alan Yeo |

In captivity, it has shown to eat soft fruits, lettuce and leaves of the wild passion fruit. However, there is no successful diet for the adults. The young can survive for some time on reconstitued powdered milk however, it eventually becomes distended with wind and die shortly after (Medway, 1983).

The diet may also contain sap from plants. In Poring, a colugo was seen licking fluid oozing from a cut on a coconut tree trunk during a heavy rain (Payne et al.,1985). However, why Sunda Colugos are usually seen licking tree trunks, is still unknown. They could be feeding on sap, or lichens for nutrients, or even licking for traces of mineral or salts (Lim, 2007). Others suggest that it could be drinking "by licking water or moisture from tree bark, leaves, mosses or any other part of the tree using its tongue" (Dzulhelmi & Abdullah, 2009).

|

| Unknown behavior of colugo licking the liana. Photo by: Norman Lim |

Fastest digestive system amongst arboreal folivores. It takes about 14 hours which is approximately only 2-10% retention time of other arboreal folivores. Hence, it is possible that Colugos have a reduce ability to digest fiber. This is supported by the observation of Colugos preferring young leaves instead of mature leaves (Lim, 2007). |

Family Life

Colugos are able to breed all year, producing a single young. There have been reports of twin births however, it is extremely rare.

Unique reproduction that is almost marsupial-like.

Despite colugos being placental mammals, their reproduction is unique and almost marsupial-like. The young is born naked and underdeveloped. It is cared for by the mother who holds it under the gliding membrane like a marsupial (Lim, 2007). When the mother glides, the baby is seen to hold on tight to the mother’s belly. |

Can you hear me?

The Sunda Colugos are usually quiet however, it has an alarm call which is described as a "loud ripping sound" (Parr, 2003). When two males are fighting and chasing, the sound is audible from a distance and is described as cracking or ripping sound. Lim, 2007 describes it as "ripping of a thick piece of cardboard". They also produce a wailing sound when caught and handled (Lim, 2007).

Locomotion

Master gliders with the most extensive gliding membrane amongst the gliders.

|

Colugos are able to glide by the use of its patagium (gliding membrane). This allows them to move through the canopy without needed to touch the ground. They are able to travel up to 145 m in a single glide and the total horizontal distance travelled by gliding per night by an individual was found to range from 130 to 1342 m (Brynes et al., 2011). However, evidence from Brynes et al. study in 2011 showed that gliding is not an economical mode of locomotion as they have a lower average angle of descent compared to other gliding mammals.

"Cute" eyes

Being a nocturnal animal, the Colugo's large forward-facing eyes are able to gather sufficient light for it to interpret its surrounding. The colugo possesses tapetum lucidum which is a reflecting tissue that acts as a "mirror" to reflect light back through the photosensitive layers hence aiding in vision in dim conditions. This creates the phenomenon known as "eye-shine". It has stereoscopic vision which allows depth perception which is important for the Colugo to judge distances accurately for safe gliding (Lim, 2007).

Sometimes, between sexes, the colugos can have eye contact for up to an hour which could be an introductory act before courtship takes place (Dzulhelmi & Abdullah, 2009).

|

| Colugo's stereoscopic vision is highly adapted for its gliding lifestyle. Photo by: Ria Tan |

Current Status

Based on the IUCN red list, the Sunda Colugo is currently classified as least concern in 2008. While it has been noted that the species is declining, the rate of decline is not fast enough for it to trigger listing in other categories of higher concern.

However, within Singapore, The Colugo is classified as "vulnerable to extinction" in the Singapore Red Data Book, 1994. This was based on a population estimate of 200. This has recently been proven somewhat too low as an Honours project conducted by Lim in 2003 gave a preliminary census that an estimate of as many as 1500 might inhabit 2000 ha of forested area in Singapore.

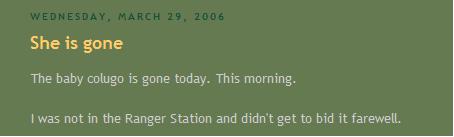

In the news

While all vertebrates in Singapore's rainforest is protected against killing and capture, it is still fairly unregulated. In 2006, a mother and baby Sunda Colugo were shot down by three men with slingshots in MacRitchie Nature Reserve. The mother colugo died while the baby was cared for by the rangers had to be put to sleep after a week as it could not survive captivity without its mother.

|

| Click to see the straits times articles |

|

| Click to read the blog involving the baby that was put to sleep eventually |

Rescue and Release

In March 2006, a colugo was rescued after it reportedly crashed into someone's house. It was then put under the care of the CNR (Central Nature Reserve) volunteers.

Read about it in their blog by clicking the pictures below for the various entries.

|

| Entry writes about trying to feed the colugo. Date: 27 Mar 2006 |

|

| Entry talks about the baby's surrogate 'mothers'. Date: 27 Mar 2006 |

Websites

ARKive

BBC Nature

Boscage

Colugos.com

Ecology Asia

EOLspecies

IUCN Red List

New World Encyclopedia

Project Noah

Tree of Life

University of Michigan Museun of Zoology

Contacts

Author of webpage: Ou Yang XiulingLast edited: 16 November 2011

Email: xiuling.ouyang@gmail.com

Literature and References

Anderson, S. & J. K. Jones (1984). Orders and Families of Recent Mammals of the World. John Wiley & Sons Inc., Canada

Arnason U., J. A. Adegoke, K. Bodin, E. W. Born, Y. B. Esa, A. Gullberg, M. Nilsson, R. V. Short, X. F. Xu & A. Janke (2002). Mammalian mitogenomic relationships and the root of the eutherian tree,Proceedings of National Academy of Science of the United States of America, 99 (12), pp. 8151-8156

Brynes, G., T. Libby & T.-L. N. Lim (2011). Gliding saves time but not energy in Malayan Colugos. The Journal of Experimental Biology 214, pp. 2690-2696

Chasen, F. N. & C. B. Kloss (1929). Notes on flying lemurs (Galeopterus). Bulletine of the Raffles Museum, Singapore, 2: 12-22

Dzulhelmi, M. N. & M. T. Abdullah (2009). An ethogram construction for the Malayan Flying Lemur (Galeopterus variegatus) in Bako National Park, Sarawak, Malaysia, Journal of Tropical Biology and Conservation, 5, pp. 31-42

Harrison, J. (1974). An Introduction to Mammals of Singapore and Malaya. Singapore Branch Malayan Nature Society, pp. 58-59

Schmitz, J., M. Ohme, B. Suryobroto & H. Zischler (2002). The Colugo (Cynocephalus variegatus, Dermoptera): The Primates' Gliding Sister?, Molecular Biology ad Evolution, 19 (2), pp. 2308-2312

Stafford, B. J. & F. S. Szalay (2000). Craniodental functional morphology and taxonomy of dermopterans. Journal of Mammalogy, 81. pp. 360-385

Lim, N. (2007). Colugo, The Flying Lemur of South-east Asia. Draco Publishing and Distribution Pte Ltd. Singapore

Martin, D. R. (2008) Colugos: obscure mammals glide into the evolutionary limelight. Journal of Biology, 7 (13)

Medway, L. (1978). The Wild Mammals of Malaya (Peninsular Malaysia) and Singapore. Oxford University Press, Kuala Lumpur

Payne, J., C. M. Francis & K. Phillipps (1985). A Field Guide to the Mammals of Borneo. The Sabah Society, Malaysia, pp. 166-167

Tweedie, M. W.F. (1978). Mammals of Malaysia. Longman, Kuala Lumpur

Walker, E. P. (1983). Mammals of the World Volume 1. John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, pp. 250-252