Tiger tail seahorse

Table of Contents

|

| Photograph courtesy of Ron Yeo @ tidechaser.blogspot.com. |

“It’s the only fish that holds your hand,” says Dr Amanda Vincent, seahorse expert and co-founder of Project Seahorse. A member of these extremely charismatic and intriguing creatures, Hippocampus comes, more commonly known as the Tiger tail seahorse by virtue of its alternately-striped tail, is the most ideal mate and dad an individual (seahorse) could ever wish for, and could be found close to home on Singapore’s shores. Read on to find out more!

ETYMOLOGY

The genus epithet 'Hippocampus' stems from greek mythology referring to a mythical creature with the head and forequarters of a horse and the tail of dolphin or a fish, on which sea gods rode [1]. In greek, 'hippos' means horse while 'campus' means sea-monster [2].

[Return to top]

INTERESTING FACTS

|

|

|

||||||

|

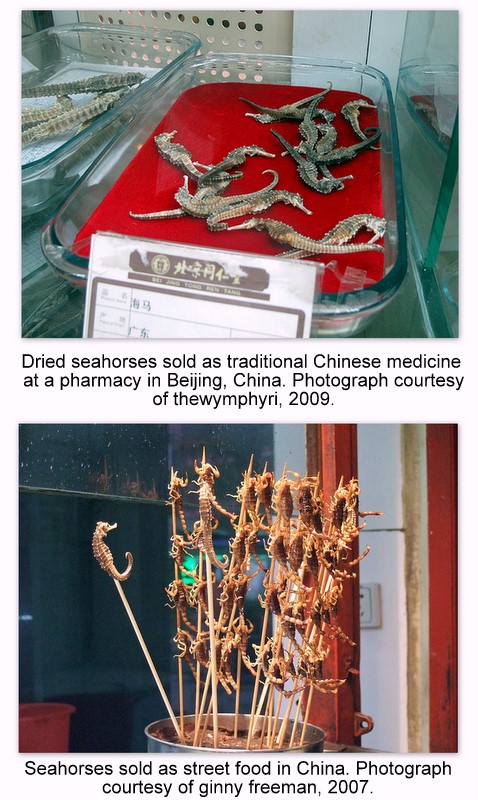

#1: The male seahorse carries the eggs during pregnancy and gives birth to live young [3]! #2: It has no stomach or teeth, and feeds on prey through suction-feeding [3]. #3: It is traded in both live and dried forms, and commonly used in traditional Chinese medicine [4]. In Singapore... according to the Singapore Red Data Book, the Tiger tail seahorse is usually found in coral reefs, mainly around the Southern Islands [5]. H. comes is listed among the threatened animals of Singapore.*Pictures displayed show H.comes found in its natural habitat on Singapore's shores. |

|

||||||

|

|

|

[Return to top]

BIOLOGY

Diet and feeding habits

The fry feed on zooplankton, mainly copepods, while adults prefer to catch benthic organisms (Amphipoda, Palaemonidae) [6]. H. comes ambushes prey by suction-feeding [7].*Video above by torvaanser, showing the Tigertail seahorse at Singapore's southern islands. At 0:17, suction-feeding by the seahorse can be observed.

Reproduction

Pregnant male H.comes. Location: Pulau Semakau. Photograph courtesy of Ron Yeo @ tidechaser.blogspot.com

Mating behaviour includes promenading and partnered revolution around holdfast structure [7]. The male seahorse exhibits specialized paternal care of young after the female seahorse deposits her eggs into the male’s brood pouch to be fertilized [8]. The male protects and nourishes the young in the pouch, provides oxygen through a capillary network and osmoregulates the developing embryos [8]. After about 2 to 3 weeks,the male actively forces the young out of its pouch, that are thereafter entirely independent of the adults [8], [9]. The male seahorse goes through more than one pregnancy in a breeding season.

In its natural environment, H. comes spawns throughout the year but the peak spawning season varies according to their distribution - in Viet Nam, peak spawning lasts from August to November, but in Philippines it is later - from September to December [6].

Life History

The gestation duration spans a period of 2 to 3 weeks, producing a brood size of approximately 200 to 300 eggs with diameter averaging 1.4mm [6], [10]. The length of H. comes at birth averages 9 mm and it is planktonic immediately after birth [10]. The first maturing size of H. comes is 119 mm in Viet Nam and 102 mm in Philippines [6]. Its breeding season has been observed to be year round in central Philippines but the peak spawning season varies according to their distribution. The life expectancy of H. comes is approximately 2.6 - 3.7 years [7].[Return to top]

ECOLOGY

Habitat

|

|

|

Behaviour

H. comes form partnerships that are sexually monogamous, accepting eggs only from one female [8]. Female H. comes may have remained faithful to the same partner because finding a new mate would be time-consuming in a population with widespread pairing, and would also be energetically costly and dangerous in terms of predation and physical damage [8]. Male and female partners perform an early morning dance together which may help in maintaining their monogamous relationship [13]. Pairs apparently come together at dusk and separate at dawn [7].This species also exhibits fidelity to a small home range, which could probably be associated with their limited swimming speed or attributed to advantages provided such as increased feeding success and survival as a result of familiarity with their surroundings, easier relocation of their mate, and facilitating crypsis [8]. It has also been proposed that finding a mate may be a precursor to site fidelity as seahorses have been observed to relocate when single and become site-faithful when in a pair [8].

In the Philippines, H. comes has been observed to be nocturnal in activity – staying within or under structure by day and rising up to grasp holdfasts at night, which could be the result of direct fishing pressure in the day selecting for a nocturnal behavioural shift in H. comes, [8].

Like other seahorses, H. comes is better suited to maneuverability than speed, with only the dorsal fin on its back providing the propulsion for its movement while its pectoral fins below the gill opening are used for stability and steering [1].

*Video above by PhuketPRN, showing the Tigertail seahorse swimming at Richlieu Rock, Thailand.

Ecological roles

- Preyed upon by crabs, large pelagic fish and humans [1].

- Important predators on bottom-dwelling organisms; therefore removing them may disrupt ecosystems.

[Return to top]

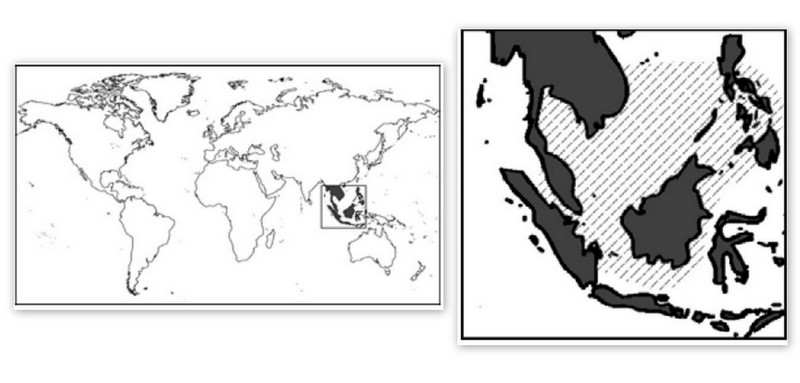

DISTRIBUTION

Wild H. comes have been confirmed in Indonesia (south Sumatra, south Kalimantan), Malaysia (Johor, Penang), Singapore, Thailand (west coast) and Viet Nam (Khan Hoa) and the Philippines [7].

|

| Distribution map of H. comes (Lourie et al., 2004) - Approval pending |

[Return to top]

THREATS |

CONSERVATION |

|

Current status H. comes is listed as Vulnerable [VU A2cd (2001)] in IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, a precautionary listing inferring overall numerical declines of 30 - 50% [7]. It has also been listed on CITES Appendix II in May 2004 [7]. Conservation action H. comes has been listed with all seahorse species(genus Hippocampus on CITES Appendix II, implemented on 15 May 2004.The 167 signatory Parties (countries) must certify, at the national level, that seahorse exports are not detrimental to wild populations and were legally acquired [7]. In the Philippines, the domestic Fisheries Code has been interpreted as banning collection of species listed on all CITES Appendices, despite the intended sustainable use provisions of Appendix II. In Malaysia, the Philippines and Thailand, no policy identifies species-level protection for H. comes although de facto security may be offered through fisheries and marine park legislation [7]. Project Seahorse This is a marine conservation group dedicated to ensuring the long-term persistence of wild seahorses and their habitats, while still respecting human rights and aspirations. Conservation-related activities thus far include managing fisheries and adjusting supplies, monitoring and adjusting consumption, policy development, biological research, education and dissemination of information [1]. In this video, produced by Invasive Films, the leaders of Project Seahorse - Dr. Heather Koldewey and Dr. Amanda Vincent, talk about seahorses, the threats they face, and how Project Seahorse's work to protect them advances the broader cause of marine conservation. To learn more about Project Seahorse, visit their main website at: Project Seahorse |

[Return to top]

TAXONAVIGATION

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Subphylum: Vertebrata

Superclass: Osteichthyes

Class: Actinopteygii

Subclass: Neopterygii

Infraclass: Teleostei

Superorder: Acanthopterygii

Order: Gasterosteiformes

Suborder: Syngnathoidei

Family: Syngnathidae

Subfamily: Hippocampinae

Genus: Hippocampus (Rafinesque, 1810)

Species: Hippocampus comes (Cantor, 1849)

[Retrieved 9 November 2011, from: Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS),]

The original name of H. comes is the same as its current name.

H. comes has commonly been synonymised with H. kuda but this is not supported by genetic and morphometric data [10].

[Return to top]

DESCRIPTION

AdultCommonly black or brown with yellow saddle shapes on their dorsal surface and yellow stripes on the tail.The snout length is about equal to the length of the rest of the head. The coronet is low with 5 rounded knob-like points, and all junctions of body ridges are surmounted by knob-like tubercles of approximately equal size. Double cheek spines border the throat at the base of the cleithral ring and double spines are usually present above the eye.*The specific details below have been extracted from Lourie et al., 2004.Maximum recorded adult height: 18.7 cm Trunk rings: 11 Tail rings: 35–36 (34–37) Height Length/Snout Length: 2.2 (1.9–2.5) Rings supporting dorsal fin: 2 trunk rings and 1 tail ring Dorsal fin rays: 18 (17–19) Pectoral fin rays: 17 (16–19) Coronet: Small and low, with five distinct rounded knobs or spines Spines: Range from knob-like and blunt to well-developed and sharp; often with dark band near tip Colour/pattern: Commonly hues of yellow and black, sometimes alternating; striped tail (may not be visible in dark specimens); mottled or blotched pattern on body; may have fine white lines radiating from eye JuvenileResembles a miniature version of the adult seahorse [10], but possesses a reduced caudal fin that is subsequently lost in adults [9]. |

|

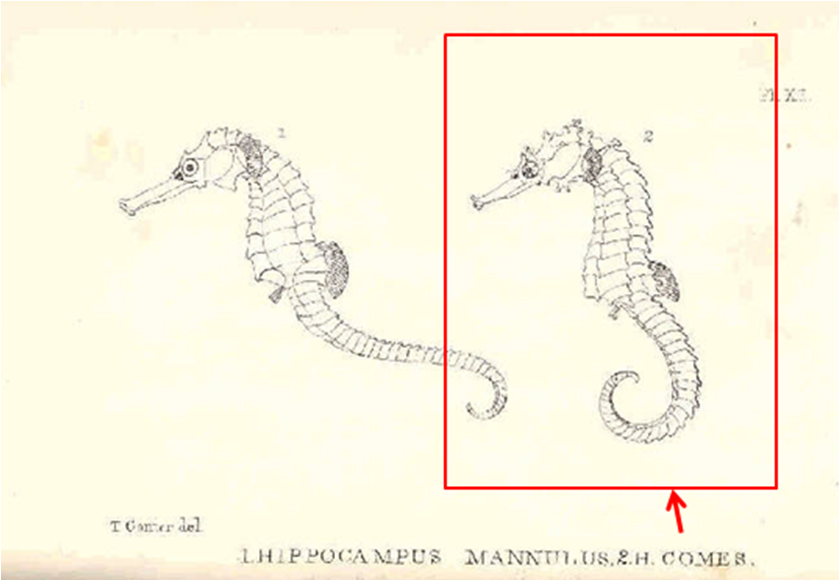

The original description of H. comes by Theodore Edward Cantor in 1849 can be found as follows:

|

| Original illustration of H. comes shown on the right (highlighted in red to show distinction). Image courtesy of the Freshwater and Marine Image Bank, University of Washington Libraries. |

| Original Name: |

Hippocampus comes 1849 |

| Journal Acronym: |

JASB |

| Journal: |

Journal and Proceedings of the Asiatic Society of Bengal |

| Article: |

Catalogue of Malayan fishes. |

| Citation: |

v. 18 (pt 2) |

| Pages: |

i-xii + 983-1443 |

| Drawings: |

Pls. 1-14 |

| Text Page: |

1371 [389] |

| Illustrations: |

Pl. 11 (fig. 2) |

*For a better view of the original illustration, click on the image on the right.

[Return to top]

DIAGNOSIS

*H. comes can be commonly confused with the similarly-sized Hippocampus kuda or Hippocampus spinosissimus, but information on its diagnosis can help to identify it correctly.

| Characteristic |

H. comes |

H. kuda |

H. spinosissimus |

||||||

| Coronet |

Low, with 5 knobs |

Rounded, turned back, may have broad flanges |

Raised, with 4 to 5 points |

||||||

| Nose spine |

Prominent |

Low or none |

Low or none |

||||||

| Cheek spines |

2 |

1, rounded |

1 or 2 |

||||||

| Snout |

Long and sender |

Thicker |

Thicker |

||||||

| Diagram |

|

|

|

[Return to top]

TYPE INFORMATION

*A holotype is the original specimen which the formal description of a new species is based on and is useful for validation purposes in future taxonomic work, such as in the identification of a newly-collected specimen. Type information on H. comes will allow other researchers to know where to look for it should the need arises.

Type locality: Sea of Pinang [Penang], Malaysia.

Holotype (unique): BMNH 1982.6.17.9 [ex 1860.3.19.532]

The holotype of H. comes can be found in The Natural History Museum, London, England, located at Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD, UK.

[Return to top]

LITERATURE CITED

- Lourie, S. A., Vincent, A. C. J. & Hall, H. J., 1999. Seahorses: an identification guide to the world's species and their conservation. Project Seahorse, London. 214 p.

- Borror, D. J., 1960. Dictionary of word roots and combining forms. Mayfield Publishing Company, Palo Alto, California. Retrieved 11 November 2011, from http://www.turuz.info/Sozluk/0271-Dictionary%20of%20word%20roots%20and%20combining%20forms%281960%29%283.659KB%29.pdf

- Project Seahorse, 2011. Why Seahorses? - Essential facts about seahorses. Retrieved 15 November 2011, from http://seahorse.fisheries.ubc.ca/why-seahorses/essential-facts

- Foster, S. J. (2008) Making non-detriment findings for seahorses, Hippocampus spp. Case study for International Expert Workshop on CITES Non-Detriment Findings. Cancun, Mexico. Retrieved 15 November 2011, from

http://www.conabio.gob.mx/institucion/cooperacion_internacional/TallerNDF/Links-Documentos/Casos%20de%20Estudio/Fishes/WG8%20CS4.pdf - Davidson, G.W.H. and P. K. L. Ng and Ho Hua Chew, 2008. The Singapore Red Data Book: Threatened plants and animals of Singapore. Nature Society (Singapore). 285 pp.

- FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Department, 2010. Hippocampus comes (Cantor, 1849) . Retrieved 9 November 2011, from http://www.fao.org/fishery/culturedspecies/Hippocampus_comes/en

- Morgan, S. K. & Lourie, S. A., 2006. Threatened Fishes of the World: Hippocampus comes Cantor 1850 (Syngnathidae). Environmental Biology of Fishes, 75:311-313.

- Perante, N. C., M.G. Pajaro, Meeuwig, J. J. & Vincent, A. C. J., 2002. Biology of a seahorse species Hippocampus comes in the central Philippines. Journal of Fish Biology, 60: 821–837.

- Foster, S. J. & Vincent, A. C. J., 2004. Life history and ecology of seahorses: Implications for conservation and management. Journal of Fish Biology, 65:1-61.

- Lourie, S. A., Foster S.J., Cooper, E.W.T., & Vincent, A.C.J., 2004. A Guide to the Identification of Seahorses. Project Seahorse and TRAFFIC North America, Washington D.C.: University of British Columbia and World Wildlife Fund.

- Project Seahorse 2002. Hippocampus comes. In: IUCN 2011. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2011.2. Retrieved 15 November 2011, from www.iucnredlist.org

- Morgan, S. K. & Vincent, A. C. J. (2007), The ontogeny of habitat associations in the tropical tiger tail seahorse Hippocampus comes Cantor, 1850. Journal of Fish Biology, 71: 701–724.

- Vincent, A. C. J., 1995. A role for daily greetings in maintaining seahorse pair bonds. Animal Behaviour, 49:258-260.

- Vincent, A.C.J. 1996. The International Trade in Seahorses. TRAFFIC International, Cambridge, UK. 163 pp.

[Return to top]

RELATED LINKS

ARKive

Catalogue of Life

Encyclopedia of Life

FAO

FishBase

FISHWISE Species Detail Page

GenBank

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species

Wild Singapore

[Return to top]

COMMENTS

Please feel free to comment or share any additional relevant information on Hippocampus comes. To comment, click on the 'Discussion' tab at the top of the page.

| Subject | Author | Replies | Views | Last Message |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Comments | ||||

[Return to top]