|

| Fig 1. Indotyphlops braminus. Photo credit: Chan Kwokwai. Image taken from Wildlife Singapore (25) |

Overview

Table of Contents

Indotyphlops braminus, belonging to the infraorder Scolecophidians, are the most ancient (basal) group of living snakes often neglected in all aspects of vertebrate studies (8). They bear similar resemblance to that of an Earthworm as a result of their worm-like appearance and size, except for the lack of segmentation which is a key feature of the annelids. About the size of a spaghetti strand, they are considered to be one of the world's smallest snake whose length averages between 6 to 16 cm (12) . Even though they are carnivorous like all other snake species, they bear no danger to humans as they are non-venomous, tiny and almost entirely blind. As such, their diets compromises of only small soft-bodied invertebrates (9) . Interestingly, I. braminus is a taxa consisting of only female individuals which reproduce solely via parthenogenesis (1). Their parthenogenetic nature and global trade of greenhouse materials essentially broaden their geographical distribution worldwide from the tropics, subtropics to temperate regions. However, the application of reproductive isolation species concepts in this taxa are not applicable due to their relatively simple body plans and parthenogenetic nature.

Etymology

The genus name "Indotyphlops" consists of "indo" which refers to the Indian to Indonesia distribution (18) and "typhlops" which is a Greek noun of "the blind" (8). The species name "braminus" is a latinized form of the word 'Brahmin' which refers to a spiritual caste among the Hindus (26).

Common Name

| Common Names |

Reason behind the name |

| Brahminy blindsnake |

Possess only a pair of rudimentary eye spots covered with translucent scales rendering them essentially blind |

| Flowerpot snake |

Commonly found living within the soil of flower pots |

| Bootlace snake |

Similar resemblance to bootlaces |

Synonyms

| Synonyms |

Authors |

| Eryx braminus |

Daudin, 1803 |

| Tortrix russelii |

Merrem, 1820 |

| Typhlops russeli |

Schlegel, 1839 |

| Typhlops braminus |

Duméril & Bibron, 1844 |

| Argyrophis truncatus |

Gray, 1845 |

| Onychocephalus capensis |

Smith, 1846 |

| Argyrophis bramicus |

Kelaart, 1854 |

| Ophthalmidium tenue |

Hallowell, 1861 |

| Typhlops (Typhlops) inconspicuus |

Jan, 1863 |

| Typhlops (Typhlops) euproctus |

Boettger, 1882 |

| Typhlops limbrickii |

Annandale, 1906 |

| Glauconia braueri |

Sternfeld, 1910 |

| Typhlops pseudosaurus |

Dryden & Taylor, 1969 |

| Typhlina braminus |

Mcdowell, 1974 |

| Ramphotyphlops braminus |

Nussbaum, 1980 |

| Indotyphlops braminus |

Hedges et al., 2014 |

Distribution

Indotyphlops braminus has an essentially cosmopolitan distribution due to the expanding international trade of greenhouse materials and their parthenogenetic nature (24). Their global distribution ranges from the tropics and subtropics of Africa, Middle East, Asia, and America, to the temperate regions of Europe and USA (26). However, with support from their relationship from the Indian and Sri Lanka sister taxa (24), they are thought to have originated from Sri Lanka or Southern India and native to Southern and Southeastern Asia.

Fig 2. Geographical distribution of I. braminus. Distribution of I. braminus are indicated by the red markers, while green markers indicate area where I. braminus are known to be introduced and considered invasive.

Habitat

Indotyphlops braminus is a completely fossorial snake species that live underground near ant and termite nest. It can be commonly found burrowed in loose, warm and damp soils of city gardens, forested, agricultural, and urban areas (12). The distribution and abundance of this snake species underground can indicate the humidity and temperature of the soil (2).

Morphological Diagnosis

At family level: Typhlopidae

Morphologically, it is easy to narrow these blindsnakes down to the family level as their characteristically small size and worm-like appearance are easily recognizable. These burrowing snakes are covered with scales of identical sizes, of which some cover and protect the eyes when burrowing while some forms shovel overlooking the mouth to enable efficient digging.

At subfamily level: Asiatyphlopinae

The family Typhlopidae are further split up into 4 subfamilies according to their dominant geographical distributions:

- Afrotyphlopinae (Africa, Arabia, India)

- Asiatyphlopinae (Asia, Oceania, North Africa, Southern Europe)

- Madatyphlopinae (Madagascar, Tanzania, Somalia, Archipelago of Comoros)

- Typhlopinae (America, West Africa)

Native to South and Southeast Asia, I. braminus belongs to the subfamily, Asiatyphlopinae.

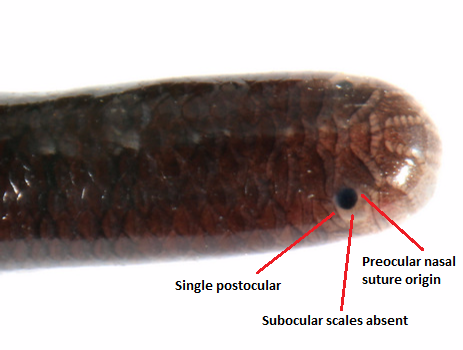

At genus level: Indotyphlops

Indotyphlops is genus that differ from the rest of subfamily, Asiatyphlopinae:

- Possesses a single postocular

- Lowest number of mid-body scales

- No scale reduction

- Smallest body length when compared to other genera, except for Cyclotyphlops

- Thinnest body

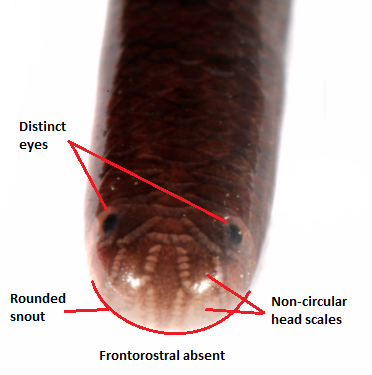

At species level: braminus

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

Character Glossary

|

| Fig 8. Head scales used as character keys. Image from Clarke et al., 2012 (5) |

Biology

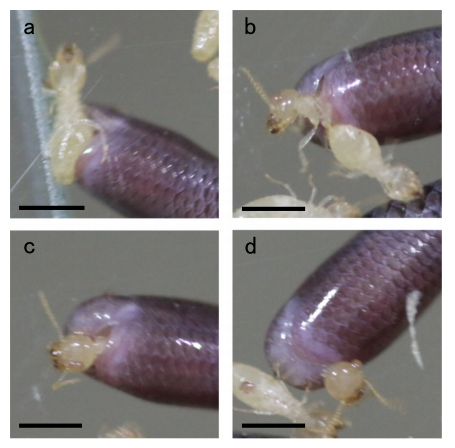

Diet

The small body size of I. braminus restricts them to a diet of small invertebrates, with preference towards those with comparatively soft bodies. They feed on the larvae and pupae of ants and termites as a prominent source of nutrients (3)(9) as well as a variety of other small invertebrates like millipedes and centipedes (9).

Vid 1. Indotyphlops braminus eating ant larvae. Video obtained from YouTube under Fair use Video adapted from BBC's Life in Cold Blood documentary series.

Predatory adaptations & behaviors

The jaws of I. braminus possesses a unique morphological design that enables their maxillary raking (upper jaw) to move independently of their skull. This enables them to pick up their preys with an efficient scooping motion as shown in the video below (16).

Vid 2. Indotyphlops braminus scooping up pupae with jaws. Video credit: Nate Kley (11).

In the predation of adult invertebrates such as termites, I. braminus are shown to exhibit a feeding behavior unusual of basal snakes. They decapitate the termites by swallowing them from the back but making sure to leave the head hanging out. They would then proceed to rub their prey against surfaces till their head fall off, before consuming the rest of the body. The termite heads are often left uneaten as they are indigestible for the snake's digestive system and possess toxic terpenes used for chemical defense. Termites head are often found undigested in the feces of I. braminus (16).

|

|

Vid 3. Indotyphlops braminus decaptitates termite. Video from Mizuno & Kojima, 2015 (16)

Defensive adaptation & behavior

Indotyphlops braminus are well adapted to a fully fossorial lifestyle. Their narrow head are consistent with their small cylindrical body covered with smooth black scales to reduce friction when burrowing. Other features also include the layer of translucent scale protecting vestigial eye spots, as well as a rigid skull and blunt nose to aid in burrowing (4)(7)(19). When threaten, I. braminus secretes foul-smelling chemicals (19) before burrowing underground to seek refuge.

Vid 4. I. braminus burrowing into soil. Video obtained from YouTube under Fair use Video credit: Noel Thomas

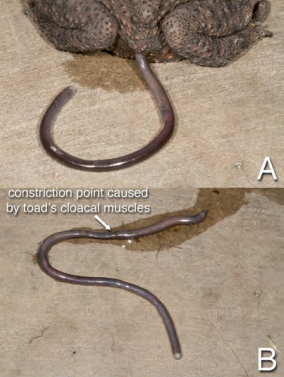

In addition, I. braminus are also very hardy creatures that are capable of living for an extended period of time without food. Herpetologist and TV personality Mark O'Shea and his team demonstrated the resilience of this snake through the documentation of a live I. braminus withstanding the journey through the digestive system of a Common Asian toad (Duttaphrynus melanostictus) and exiting through its rear end (11).

|

| Fig 11. I. braminus found exiting the the gastrointestinal system of D. melanostictus. Image from O'Sheal et al., 2013 |

Reproduction & Development

Indotyphlops braminus is a female-only species which reproduces via parthenogenesis to produce genetically identical offspring. They are oviparous and can lay from 2-8 tiny eggs each time (12). Each of these unfertilized eggs can hatch into female hatchlings of approximately 53 mm in length (9) and potentially establish new colonies elsewhere by itself, requiring only sufficient food source and suitable soil conditions.

Ecological Significance & Conservation

Indotyphlops braminus preys on soft-bodied invertebrates and play an essential role as a secondary consumer in the ecosystem by keeping the populations of small invertebrates such as ants and termites in balance.

However, as I. braminus are highly tolerant to disturbances (9) and capable of establishing colonies with just a single individual, they are distributed widely around the globe and considered invasive in the non-native regions. As such their conservation status is yet to be assessed on the ICUN Red List (17) as there are no known threats to this species,

Taxonomy & Systematic

Type information

Lectotype: Russell 1796, plate 43

Type locality: Vizagapatam, India

Classification

The Taxo-navigation system below is provided by and referenced to UniProt Taxonomy. This reflects the classification of Indotyphlops braminus above the species level.

› cellular organisms

› Eukaryota

› Opisthokonta

› Metazoa

› Eumetazoa

› Bilateria

› Deuterostomia

› Chordata

› Craniata

› Vertebrata

› Gnathostomata

› Teleostomi

› Euteleostomi

› Sarcopterygii

› Dipnotetrapodomorpha

› Tetrapoda

› Amniota

› Sauropsida

› Sauria

› Lepidosauria

› Squamata

› Bifurcata

› Unidentata

› Episquamata

› Toxicofera

› Serpentes

› Typhlopoidea

› Typhlopidae

› Indotyphlops

Phylogeny

The species delimitation of blindsnakes from Southern and Southeastern Asia have been especially challenging due to its comparatively lack of useful morphological characters (8). In addition due to the subjectivity of morphological classification, the parthenogenetic nature of I. braminus render process-based species concepts like Biological Species Concept and Hennigian Species Concept inapplicable due to the lack of sexual reproduction between each individuals of the same species. As such, there have been much disagreements with regards to the classification of these blindsnakes (10)(20)(21)(22)(23).

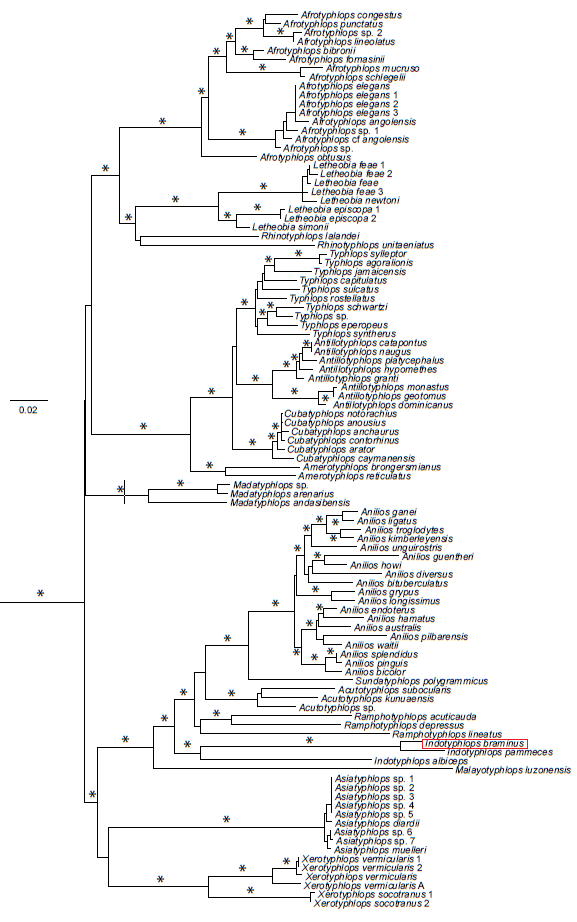

In most cases, these blindsnakes are grouped under the genus Ramphotyphlops and Typhlops based on morphological and ecological similarities like non-venomous nature, rudimentary optical sensory, diet and habitat preferences. However, phylogenetic analysis of molecular data revealed lineages that are clearly divergent such as the family,Gerrhopilidae (20). Subsequent molecular evidence also enabled more species to be classified into genus like Anilios, Malayotyphlops, Ramphotyphlops s.s., and Sundatyphlops (13)(14), while remaining species were allocated into genus Asiatyphlops and Indotyphlops. As such, relationship within the genus Indotyphlops are less established (8). However, the establishment of I. braminus (global invasive species) and I. pammeces (Indian species) being closest related sister taxa with strong support (high bootstrap and posterior probability) do suggest probable Indian origin for the genus Indotyphlops.

|

| Fig 12. Phylogenetic Maximum Likelihood tree of typhlopid snakes based on an analysis of DNA sequences of five nuclear protein-coding genes, BDNF, RAG1, BMP2, NT3, and AMEL. Nodes with posterior probability > 95% and ML bootstrap probability > 70% are indicated with asterisks (*). The tree is rooted with 22 outgroupspecies (not shown) including a monitor lizard, and species of alethinophidian, leptotyphlopid, gerrhopilid, and xenotyphlopid snakes. Figure adapted from Vidalet al. 2010. |

References

- Baker, N. (n.d.). Brahminy Blind Snake - Ramphotyphlops braminus. Retrieved November 10, 2015, from http://www.ecologyasia.com/verts/snakes/brahminy_blind_snake.htm

- Brahminy Blindsnake - Ramphotyphlops braminus. (n.d.). Retrieved November 5, 2015, from http://www.californiaherps.com/snakes/pages/r.braminus.html

- Brahminy blind snake photos and facts. (n.d.). Retrieved November 4, 2015, from http://www.arkive.org/brahminy-blind-snake/ramphotyphlops-braminus/

- Burnie, D. (2001). Animal: Dorling Kindersley. London. pp.

- Clarke, DN, Kunkel, W, Chippaux, JP, and Jackson, K. 2012. Online multivariate key to the snake genera of Western and Central Africa. Retrieved November 14, 2015, from http://people.whitman.edu/~clarkedn/

- Durso, A. (n.d.). Life is short, but snakes are long. Retrieved November 9, 2015, from http://snakesarelong.blogspot.sg/

- Halliday, T. and Adler, K. (2002) The New Encyclopedia of Reptile and Amphibians. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Hedges, S. B., Marion, A. B., Lipp, K. M., Marin, J., & Vidal, N. (2014). A taxonomic framework for typhlopid snakes from the Caribbean and other regions (Reptilia, Squamata). Caribbean Herpetology, 49, 1-61.

- Hellyer, P. and Aspinall, S. (2005) The Emirates: A Natural History. Trident Press Limited, United Arab Emirates.

- Khan, M. S. (1999). Two new species and a subspecies of blind snakes of genus Typhlops from Azad Kashmir and Punjab, Pakistan (Serpentes: Typhlopidae). Russian Journal of Herpetology, 6(3), 231-240.

- Kley, N. J. (2001). Prey transport mechanisms in blindsnakes and the evolution of unilateral feeding systems in snakes. American Zoologist, 41(6), 1321-1337.

- Krysko, K. (n.d.). Indotyphlops braminus. Retrieved November 9, 2015, from https://www.flmnh.ufl.edu/herpetology/fl-snakes/list/indotyphlops-braminus/

- Marin, J., Donnellan, S.C., Hedges, S.B., Doughty, P., Hutchinson, M.N., Cruaud, C. & Vidal, N. (2013a) Tracing the history and biogeography of the Australian blindsnake radiation. Journal of Biogeography, 40, 928–937.

- Marin, J., Donnellan, S.C., Hedges, S.B., Puillandre, N., Aplin, K.P., Doughty, P., Hutchinson, M.N., Couloux, A. & Vidal, N. (2013b) Hidden species diversity of Australian burrowing snakes (Ramphotyphlops). Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 110, 427– 441.

- McDowell, S. B. (1974). A catalogue of the snakes of New Guinea and the Solomons, with special reference to those in the Bernice P. Bishop Museum, Part I. Scolecophidia. Journal of Herpetology, 1-57.

- Mizuno, T., & Kojima, Y. (2015). A blindsnake that decapitates its termite prey. Journal of Zoology, 297(3), 220-224.

- O’Shea, M., Kathriner, A., Mecke, S., Sanchez, C., & Kaiser, H. (2013). ‘Fantastic Voyage’: a live blindsnake (Ramphotyphlops braminus) journeys through the gastrointestinal system of a toad (Duttaphrynus melanostictus). Herpetology Notes, 6, 467-470.

- Pyron, R. A., & Wallach, V. (2014). Systematics of the blindsnakes (Serpentes: Scolecophidia: Typhlopoidea) based on molecular and morphological evidence. Zootaxa,3829(1), 1-8

- The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2015-3. <www.iucnredlist.org>. Downloaded on 10 November 2015.

- Vidal, N., Marin, J., Morini, M., Donnellan, S., Branch, W. R., Thomas, R., Vences, M., Wynn, A., Cruaud, C. & Hedges, S. B. (2010). Blindsnake evolutionary tree reveals long history on Gondwana. Biology Letters, 6(4), 558-561.

- Wallach, V. (1999). Typhlops meszoelyi, A new species of blind snake from northeastern India (Serpentes: Typhlopidae). Herpetologica, 185-191.

- Wallach, V. (2000). Critical review of some recent descriptions of Pakistani Typhlops by MS Khan, 1999 (Serpentes: Typhlopidae). HAMADRYAD-MADRAS-, 25, 129-143.

- Wallach, V., & Pauwels, O. S. (2004). Typhlops lazelli, a new species of Chinese blindsnake from Hong Kong (Serpentes: Typhlopidae). Breviora, 1-21.

- Wallach, V. (2009). Ramphotyphlops braminus (Daudin): a synopsis of morphology, taxonomy, nomenclature and distribution (Serpentes: Typhlopidae). Hamadryad, 34, 34-61.

- Wildlife Singapore - Brahminy Blind Snake. (n.d.). Retrieved November 3, 2015, from http://www.wildsingapore.per.sg/fauna/facts/snake_blind.htm

- Uetz, P., & Hallermann, J. (n.d.). Indotyphlops braminus (DAUDIN, 1803). Retrieved November 11, 2015, from http://reptile-database.reptarium.cz/species?genus=Indotyphlops&species=braminus

Contact Me

Lee Zhi Heng is contactable at zhihenglee91@gmail.com