Muntingia calabura (Linnaeus, 1753)

Table of Contents

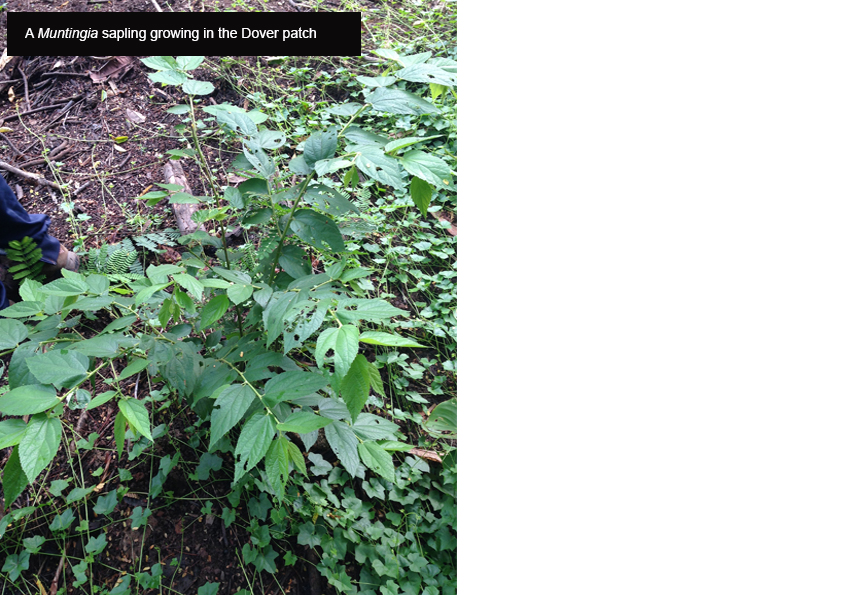

Photo by Germaine Tan, NUS behind block S3, 2015

The Basics

The Jamaican Cherry Tree, as the name suggests, is an exotic species so widely naturalized that in some parts of Southeast Asia, it was thought to be native by the local people.[1] This webpage discusses the unique characteristics, potential uses to humans (particularly in medicine), roles in ecology and taxonomic background of this species.Synonyms:[2]

Muntingia calabura var. trinitensis Griseb.

Muntingia rosea H.Karst.

Local vernacular names:[1]

Jamaican cherry

Japanese cherry

Buah cheri

Kerukup siam

How to Identify this Tree?

The Jamaican cherry is easily identifiable. It has very distinctive characteristics and you should be able to recognise it based on sight and touch.Diagnostics

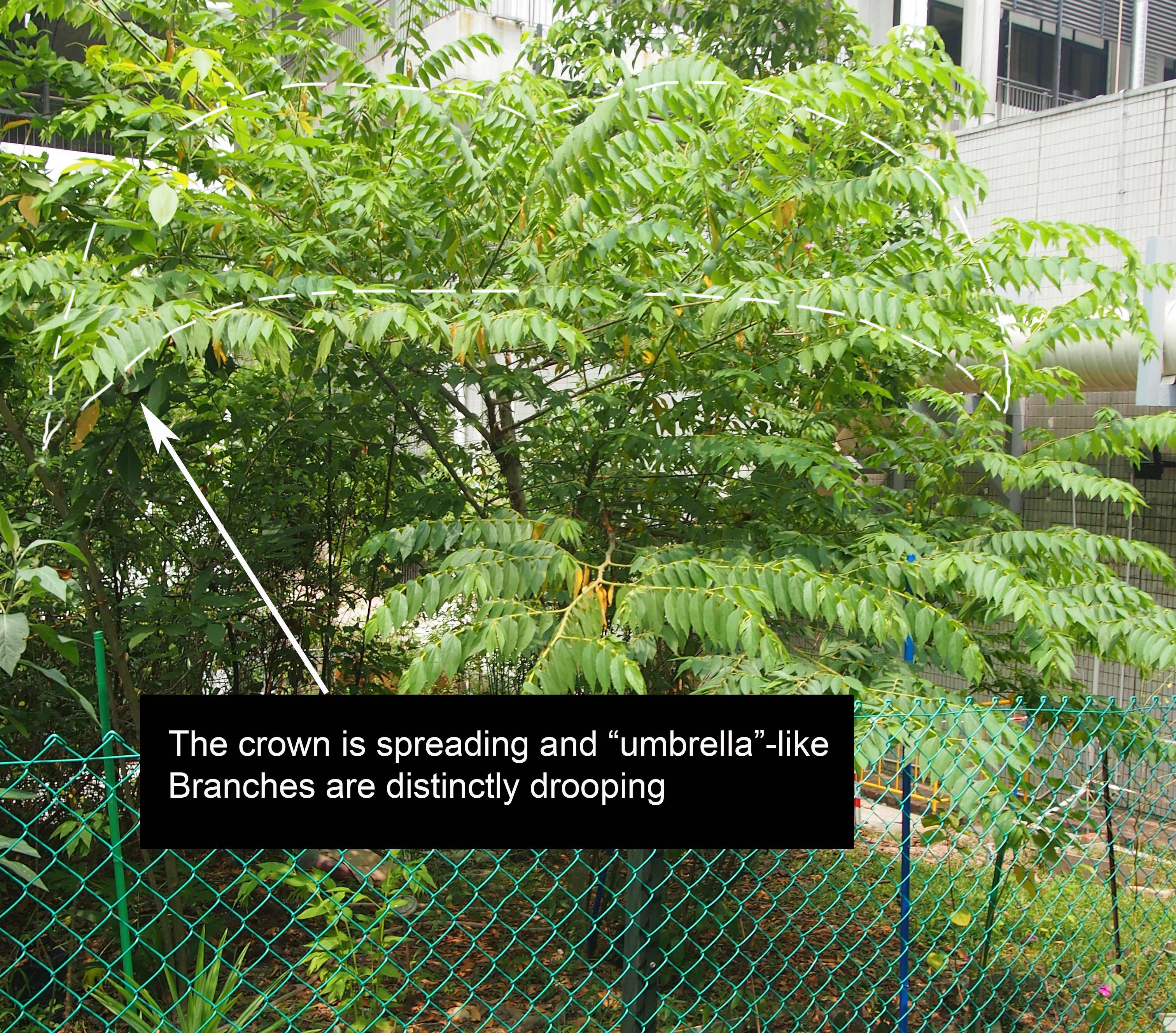

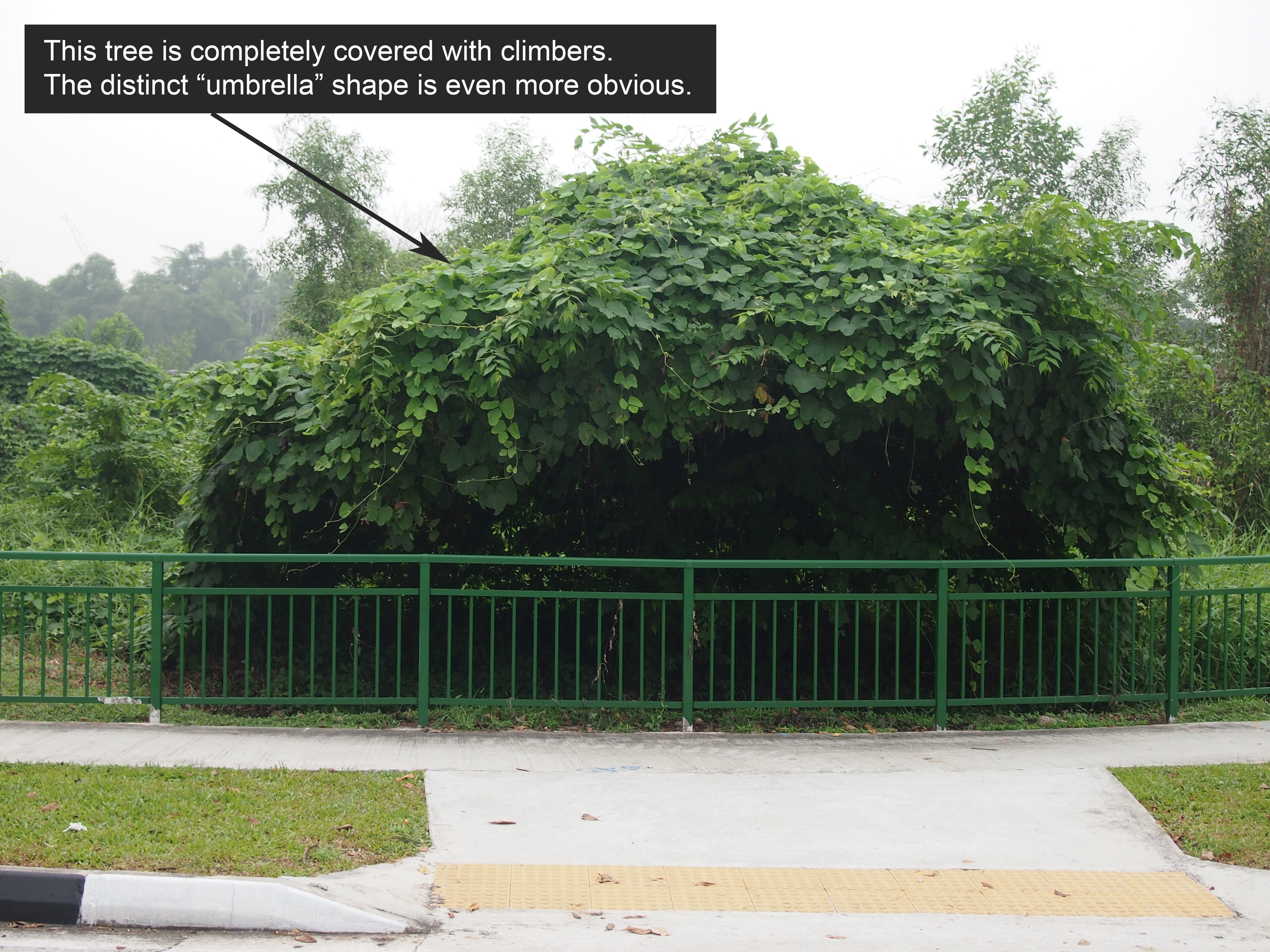

(Adapted from [1] [3] [4] )A rather short evergreen tree (max. 7.5–12 m tall) with a wide crown and drooping branches that spread almost horizontally. Leaves are simple, alternate, lanceolate,oblique,drooping and with toothed margins (especially towards the pointed tips). Twigs and leaves are covered in tiny hairs and are sticky to the touch. Distinct 45-degree branching patterns. Flowers are white with 5 petals, about 1.5–2cm in size. Unripe fruits are round, usually ripen from green to red (or sometimes yellow) and the ripe fruit is filled with tiny yellowish seeds that exude when the fruit is squeezed. It flowers all year round.

Some useful pictures

(All photos are by Germaine Tan, 2015)

See this useful pagefor more photos to help in identification.

Confusion?

This species is supposedly similar in general to the members of Malvaceae (Mallow family) and especially species of the genus Grewia, which bear symmetric leaves with strongly toothed margins.[5] The Grewia species known to occur locally in Singapore[6] [7] are:- Grewia laevigatawhich has leaves of a different texture: it is not sticky but more like sandpaper.[8]

- Grewia occidentaliswhich has purple flowers instead of white.

Jamaican in Singapore

Status

Exotic, Naturalised.[7]Distribution

Native to Mexico, Central America, tropical South America, the Greater Antilles, St. Vincent and Trinidad. In tropical regions such as India, Southeast Asia (including Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia and the Philippines), as well as some warm regions of the New World, the species is not native but widely cultivated.[2]How did it get here?

This tree was first introduced to the Philippines in the late 19th century.[9] Its seeds are widely dispersed by birds and bats, which probably aided its spread to Thailand, down the Malay Peninsula and eventually to Singapore.[10] The first official record of this species on our land was written in 1895.[11]

Image by Germaine Tan, base map is from Google Maps.

Is it invasive?

This is often a concern when dealing with exotic species. It is also a widely debated subject among ecologists. Pacific Island Ecosystems at Risk (PIER)has declared the species as having a high level of invasion potential,[12] but it is worth noting that this database has stopped being updated from 2013 onwards. Muntingia calabura is currently not listed as an invasive species on IUCN’s Global Invasive Species Database (GISD).[13]Recently published literature by Ngheim et al.[11]considered Muntingia calabura as a possible invasive species in Singapore, based on expert opinion and growth rate experiments. However, its shade-intolerant saplings and small seeds make it an unlikely threat to the largely native-dominated closed-canopy forests. It is most commonly found established in abandoned wastelands, which have no lack of exposure to sunlight.

Further studies can be done to suggest possible conservation action. My personal view is that until there is enough substantial evidence that this species has the capability to invade into and outcompete the natives in the closed-canopy forests, there is some value in allowing this exotic to grow in the wastelands because of its existing contributions to the local ecosystem and its association with native fauna (see next section on uses and ecology). Its multitude of potential human uses (as timber etc.) also render it a useful species to have around, because it can be felled, harvested and put to good use if found to be growing in areas where it is not welcome.

Where to find it?

It seems that the bark and wood is not being harvested for use in this urban country (the rural kampong areas might be exceptions), and neither are the fruit, flower or leaves a popular delicacy here. It is also not popular as an ornamental due to its shabby appearance, and because it attracts bats and birds which make a mess with their droppings.[4] Hence, it is most commonly found spontaneously growing in wastelands and rural areas. [10]Map of occurrences

I have found this tree growing in patches of wastelands and even construction sites along roads. Some specific locations that I know of:

- NUS, growing in a garden outside block S3 and behind pharmacy block (S4). There is also one growing in the ditch at the first floor of S3 outside LT20.

- Patch of forest next to Dover MRT

- Many in the wasteland patch opposite TradeHub21 (Boon Lay Way, pictured below)

- At least one growing at the construction area along Dunearn road before Eng Neo Avenue

(Photos by Germaine Tan, 2015)

The Giving Tree

(Information on uses and ecology adapted from [2] unless otherwise mentioned.)

Human uses

- Wood:

- Carpentry—Timber is quite strong, lightweight, long-lasting and malleable, making it suitable as a material for small storage boxes etc.

- Firewood—Dried wood produces strong heat with minimal smoke, catches fire easily, so it is often used in cooking

- Papermaking—in Brazil

- Bark:

- Ropes—Stripped to make twine or ropes because the material is strong and soft. It has been used to secure supports in the building of rural houses.

- Fruits:

- Food—Sweet and edible. Sold as the fruit itself in Mexican markets, sometimes made into jams and even tarts. Said to be a popular choice among children in the past, who would pluck the sticky fruit by hand.

- Medicine—Studies have shown the fruits to be rich in antioxidants.[14] It is likely to protect against cervical cancer in humans as it contains cytotoxic chemicals.[15]

- Insecticide—Fruits have also been shown also to contain insecticidal compounds, hence have the potential to be developed into commercial insecticides.[16]

- Fishing—The Brazilians are known to plant the trees on riverbanks. Ripe fruits drop into the water and serve as bait. Fishes are attracted to the surface and caught by the fishermen.

- Leaves:

- Food—Dried and made into a tea infusion.

- Medicine—Leaf extracts have been shown in pharmacological studies to possess antibacterial,[17] [18] antipyretic and anti-inflammatoryactivity.[19] It has antinociceptive (i.e. pain relieving) compounds [19] [20] [21] [22] and can protect against gastric ulcers. [23] [24] [25] Some studies have found compounds with cytotoxic activity suggested its possible use as an anticancer agent.[26] It has also been found to contain compounds that protect against myocardial infection;[27] the leaf extracts seem to have a hypotensive effect on the body.[28]

- Flowers:

- Medicine—used as an antiseptic, spasm treatment, analgesic (relieve headaches) and a remedy to cold.

- Insecticide—Potential to be developed into commercial insecticides.[16]

- Roots:

Ecological roles

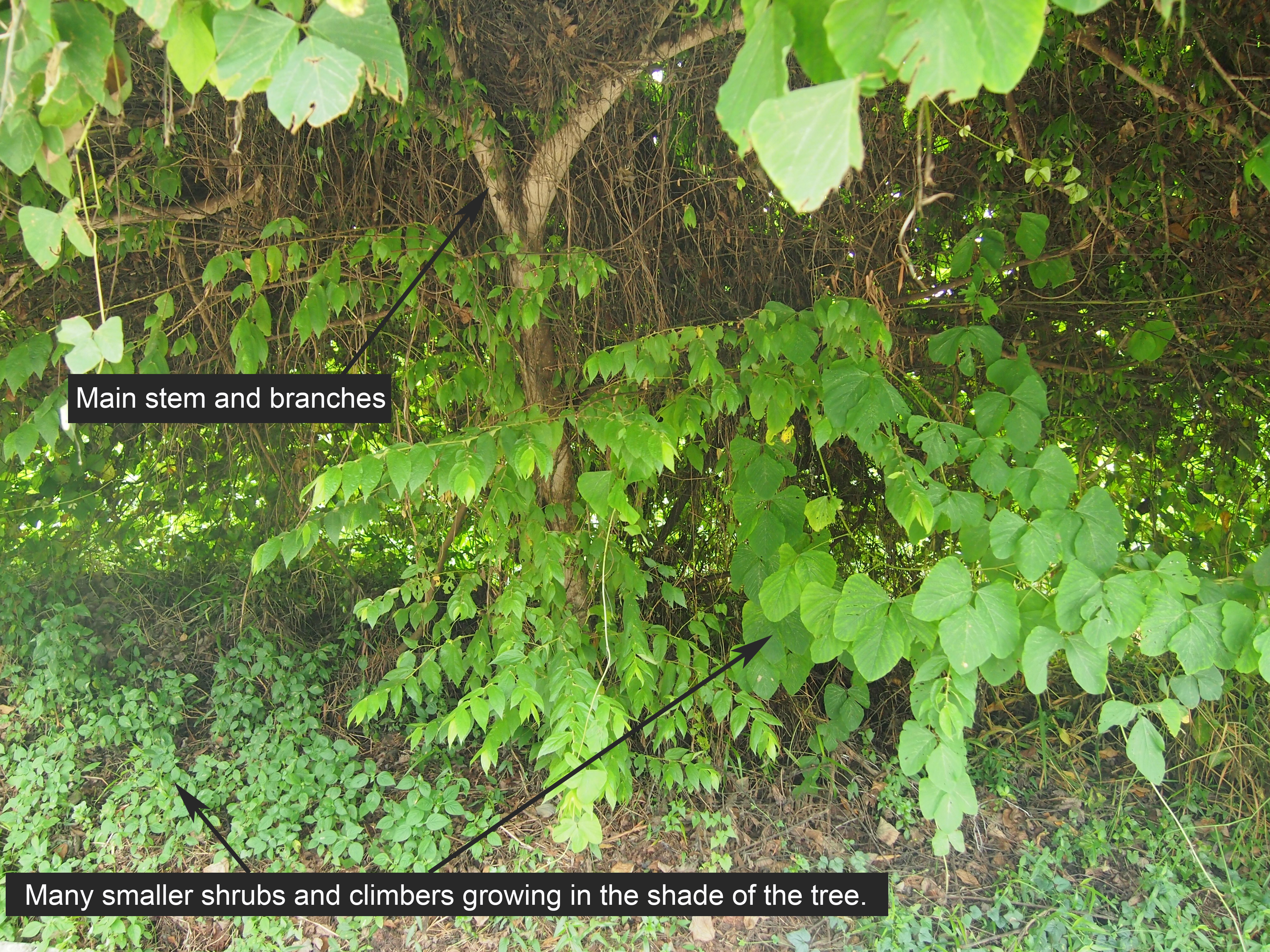

- Shade—This species is fast-growing and can thrive on soil with low nutrient content. Hence it is a pioneer species in such environments and its wide crown provides shade for other plants to start to grow.

This Muntingia calabura was found growing in the wasteland opposite TradeHub21 (Boon Lay Way). A closer look at the shade environment it creates is seen in the photograph below:

(Photos by Germaine Tan, 2015)

- Shelter—Home to small animals.

- Food—Flowers provide nectar to the bees that pollinate them; ripe fruits are eaten by birds, bats and squirrels, which disperse their seeds. Because of its popularity among animals as a food source, it has been suggested as a species for planting in wildlife sanctuaries.

The Bird Ecology Study Grouphas reported the following birds as sighted eating the berries:[31]- Pink-necked Green Pigeon (Treron vernans)

- Lineated Barbet (Megalaima lineata)

- Asian Glossy Starling (Aplonis panayensis)

- Yellow-vented Flowerpecker (Dicaeum chrysorrheum)

- Orange-bellied Flowerpecker (Dicaeum trigonostigma)

- Scarlet-backed Flowerpecker (Dicaeum cruentatum)

- Asian Koel (Eudynamys scolopacea)

A honey bee feeding on the nectar of the Muntingia's flower. (Photo by Germaine Tan, 2015)

- Reforestation—Muntingia calabura was considered as a candidate species in reforestation projects in the Philippines because of its fast growth and ability to survive droughts and in nutrient-poor soils. It was favoured for planting in grasslands because it could outcompete weedy grass such as cogon. Although not native to the region, it had already become so extensively naturalized that it was “found practically in all parts of the country”, and they believed that growing this pioneer species would improve soil condition and aid natural succession.[32] More recent news reports Philippines’ intention to reforest Corregidor islandwith fruit-bearing species including Muntingia calabura. The exotic status does not seem to be a concern, and their focus is on attracting wildlife (especially birds) to improve their tourism industry.[33]

What’s in a name?

Etymology (Scientific name):Genus was named (by Linneaus) after Abraham Munting(1626-1683), a Dutch botanist and physician. The meaning of the specific epithet is unsure, but it is known to be West Indian.[3]

Etymology (Vernacular name):

The common name “Jamaican Cherry” can be somewhat misleading because botanically speaking, the fruit is a berry and not a cherry. The shape and colour of the fruit (red, round and with a stalk) as well as the white-coloured flowers makes the tree look superficially similar to a real cherry tree. A real cherry in the botanically correct definition is the fruit of the genus Prunus (family Rosaceae) bearing a large, singly-seeded stone. Nevertheless, the name “Jamaican Cherry” is widely used as it is the most correct out of the vernacular names—the tree originated from tropical America (the type specimen was originally described in Jamaica) and not Japan, Singapore or other parts of Asia.[3]

Phylogeny and Classification:

Classification:Kingdom: Plantae

Subkingdom: Viridiplantae

Infrakingdom: Streptophyta (land plants)

Superdivision: Embryophyta

Division: Tracheophyta (vascular plants)

Subdivision: Spermatophytina (seed plants)

Class: Magnoliopsida (flowering plants)

Superorder: Rosanae

Order: Malvales

Family: Muntingiaceae

Genus: Muntingia L.

Species: Muntingia calabura L.

(Adapted from [34] as of 5 November 2015)

It belongs to a monotypic genus i.e. it is the only species in the genus Muntingia.

Complicated family history:

Historically, the systematic position of Muntingia calabura has been contentious. It was originally placed under either Tiliaceae (also known as Malvaceae) or Elaeocarpaceae, but the genus exhibits unique characters that do not fit with either of the families. In 1998, Bayer et al.[35] used DNA sequencing to show that the species should be reclassified as its DNA sequences showed little relation to the families to which it was previously associated. There was enough molecular evidence for Muntingia to be excluded from the other families and placed in a family of its own, Muntingiaceae.[36] Although it is placed in the order Malvales, it does not form a monophyletic group with the core families in the order. Its placement within the order is still unclear. See herefor a proposed phylogenetic tree and brief discussion on the phylogenetic relationships of the order Malvales.[37]

Linnaeus and his Species Concept

Type specimen

The species was first described by Carl Linnaeus, in his book Species Plantarum, Volume 1: page 509, published on 1 May 1753.[38] The original Latin description can be found online, here.Most of Linneaus’ plant specimens have been well documented and digitalized under the Linneaen Plant Name Typification Project.

In cases where the species was originally described based on more than one specimen, the specimens are considered syntypes. A lectotype may be subsequently designated. In this case, the lectotype was designated by Dorr, in C. E. Jarvis et al., Regnum Vegetabile. 127: 68. 1993.

Details on type specimen, retrieved from International Plant Names Index (IPNI),annotated for ease of understanding.

See the type specimen here.

Which Species Concept?

In the time of Carl Linnaeus, modern species concepts did not yet exist. Science historians have studied his work in an attempt to infer what the Father of Taxonomy considered as a “species”.Many consider the Typological Species Concept to be the species concept of Linnaeus and his followers.[39] [40] [41] As a Christian, he believed in a divine Creator who designed each species to give rise to more of its own kind. He believed that species were real and their numbers were unchanging.[40] One author claims that this belief in “types” was constructed based on Linnaeus' naïve faith in God.[41]

He famously said: "Species are as many as were created in the beginning by the Infinite." (Linnaeus, 1758)

Based on this concept, each species was expected to have a different morphology because it belonged to a different “type”. Hence, they were described based on morphological data. This kind of belief where species are recognized by their “essential characters” is now referred to as “essentialism”.[39] Linnaeus formed criteria on which traits to use. He judged traits worthy or unworthy based on their stability. He did not use plastic traits such as flower colour or body size because these could be affected by soil pH (or other environmental factors) and age respectively. Instead, he used mainly the sexual system (i.e. the male and female sexual organs) of flowering plants to describe and classify species. This classification based on an inferred sexual compatibility is very similar to the idea of reproductive isolation adopted by modern Biological Species Concept. Although the concept of gene flow did not yet exist, he was able to intuitively classify sexually incompatible organisms as separate species.[42]

However, Linnaeus’ classification was not strictly and solely based on morphology. He was said to have described the male and female mallard duck as different species because they looked different. However, upon discovering his mistake he had merged the two into the same species immediately without a fuss, despite the obvious morphological differences.[39] This further supports the notion that there was some biology involved and his species concept was not purely morphological.

The grouping of specific traits into taxa bears some resemblance to the modern Phenetic Species Concept. The main difference is that Linnaeus truly believed that the different “types” existed, while pheneticists do not—their concept is merely an operational tool used for grouping. Although species and genus were real to him, he considered, like modern taxonomists, any higher taxa above genus to be artificial constructs.[42]

A more recent paper[43] however argues against this common belief that Linnaeus was essentialist. Linnaeus had apparently changed his view that species are absolutely fixed and in the later part of his life was a believer in limited transmutation. Winsor claims that rather than believing in absolute essentialism, Linnaeus was rather accepting of the idea that God created one species per genus and the rest evolved from natural processes. This may have to do with the fact that he observed a number of instances of hybridization in plants in his lifetime,[41] which led to his partial belief in evolution, which had at that time yet to be suggested by Darwin.

See herefor more quotes by Linnaeus on species.

Other useful websites

On Muntingia calabura:http://www.naturia.per.sg/buloh/plants/cherry_tree.htm

http://uforest.org/Species/M/Muntingia_calabura.html

https://www.hort.purdue.edu/newcrop/morton/jamaica_cherry.html

On species concepts:

https://www.mun.ca/biology/scarr/2900_Species.html

References

- ^ Morton, J. (1987). Jamaica Cherry. p. 65–69. In: Fruits of warm climates. Julia F. Morton, Miami, FL.https://www.hort.purdue.edu/newcrop/morton/jamaica_cherry.html

- ^ The Plant List. (2013). Version 1.1. Retrieved 8 November 2015, from http://www.theplantlist.org/

- ^ Corner, E. J. H. (1997). Wayside trees of Malaya: Vol I (4th ed.) (pp. 251–252.). Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Malayan Nature Society.

- ^ Wee, Y. C. (1989). A Guide to the Wayside Trees of Singapore (p. 145.), Singapore: Singapore Science Centre.

- ^ LaFrankie, J. (2010). Trees of tropical Asia (p. 462). Philippines: Black Tree Publications.

- ^ National Parks Board, Singapore (2013). Flora Fauna Web - Home. Retrieved 9 November 2015, from https://florafaunaweb.nparks.gov.sg

- ^ Chong, K. Y., Tan, H. T. W. & Corlett, R. T. (2009). A Checklist of the Total Vascular Plant Flora of Singapore: Native, Naturalised and Cultivated Species (273 pp.). Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research, National University of Singapore, Singapore.

- ^ Slik, J.W.F. (2009 onwards) Plants of Southeast Asia. Retrieved 26 October 2015, from http://www.asianplant.net .

- ^

http://www.ipni.org/ipni/idPlantNameSearch.do?id=320779-2&back_page=%2Fipni%2FeditSimplePlantNameSearch.do%3Ffind_wholeName%3Dmuntingia%2Bcalabura%26output_format%3Dnormal