|

| Stone or Thunder crab. Photo by Suhailah Isnin. |

Diagnosis | Description | Biology | Ecology | Name | Taxonomy | Phylogeny | Type information | Links to other online sources | Literature cited

The myth behind the name: Thunder crab

Myomenippe hardwickii or commonly known as the Stone or Thunder crab is a small to medium-sized crab which is usually encountered in mangroves and intertidal shores. Using its massive and powerful chelipeds (pincers), it can crush its shelled preys such as the bivalves (clams) and gastropods (snails).[1] Legend has it that if it pinches you, the only way for it to release its grip is by a clap of a thunder and hence, the name Thunder crab. However, this is untrue. The best option for the crab to let go of its grip is to place it on the ground near to its hiding place (rock crevices) and eventually, it will release its grip and scurry back to its hiding place.[2] Nevertheless, it is harmless if you do not handle it.

Therefore, if you are interested to learn more about the Thunder crab, look no further because this site will equip you with the scientific information you need to know about this crab. Not only that, it is also a stepping stone for young aspiring crab biologist out there to gain knowledge about crab biology. Hence, fret not if you are not familiar with the scientific terms used as simple definitions are provided in this site. By the end of this site, hopefully, you will be on your way to becoming a crab biologist!

Diagnosis

[Identification of species using distinguishable feature] |

| Maroon Stone crab. Photo by Ria Tan (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0). |

First and foremost, a crab biologist has to know which features to look for when he or she is going outfield to search for a particular crab species. Every crab species has its own distinguishable features. For example, the number of the teeth (protrusions which can be either sharp or blunt) at the edge of the carapace (shell) or chelipeds (pincers) can tell different crab species apart. Colour, however, is not a good way to diagno

se a crab species as colours may vary depending on th

e diet of the crabs. As for M. hardwickii, it is relatively easy to spot it due to its distinct eyes.

Under the genus Myomenippe, there are two species: M. hardwickii and Myomenippe fornasinii (Bianconi 1851).[4] M. fornasinii does not occur in Singapore but it is widely distributed in the Northern coast of Australia.[5] The closest relative to M. hardwickii that can be found in Singapore is Menippe rumphii (Fabricius 1798) commonly known as the Maroon Stone crab, which is under the same family Menippidae as M. hardwickii.

M. hardwickii has a distinguishable feature to tell it apart from other similar species. It has bright green eyes surrounded by a ring of red and it is often mistaken for M. rumphii which has all red eyes.[1]

|

| Thunder crab's green eyes ringed with red. Photo by Suhailah Isnin. |

|

| Maroon Stone crab's all red eyes. Photo by Ria Tan (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0). |

Back to top

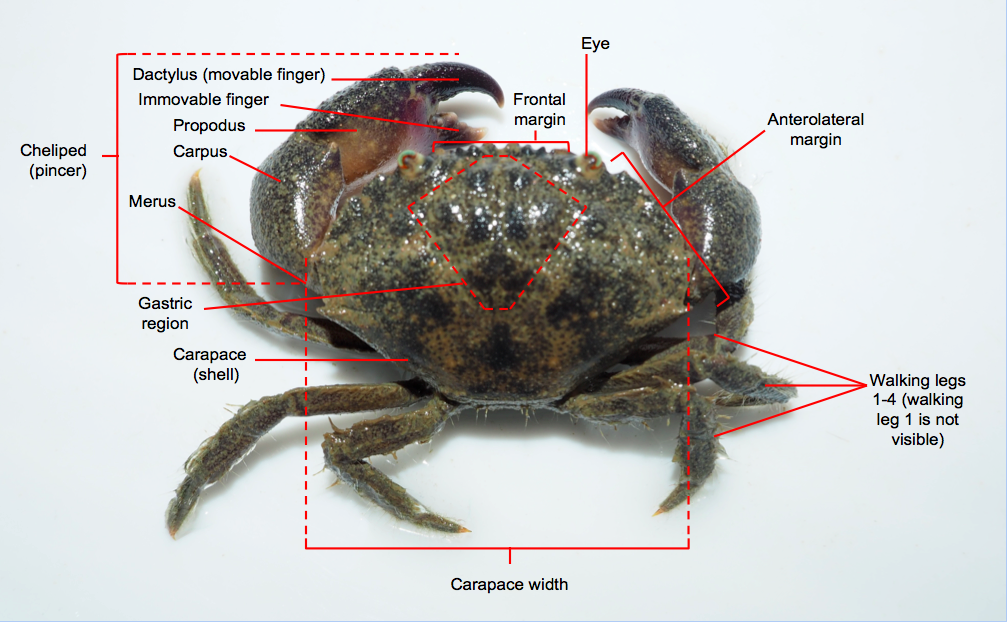

Description

[Morphological (physical) description of species]After identifying the crab, the next thing a crab biologist should know is to describe the crab's morphological (physical) features. For example, he or she should know if a crab species has hairy walking legs or unequal size of chelipeds (pincers). The parts of M. hardwickii are labelled and described in a table form below.

|

| Dorsal (upper) view of Thunder crab with annotations. Photo by Suhailah Isnin. |

| Eyes |

- green eyes, often ringed with red |

||

| Carapace (shell) |

- colour ranging from dirty brown, reddish brown to greenish brownish yellow (depends on diet) - hexagonal (six-sided) - broader than long (width can reach up to 12cm) - convex - smooth texture covered with numerous tiny granules |

||

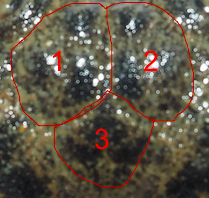

| Gastric region (location of stomach) |

- divided into three regions - surface of two antero-lateral gastric regions is broken into two low granular convexities (bulges)

|

||

| Frontal margin (area between the eyes) |

- divided into two lobes which is separated by a notch (N) (depression) in between - each lobe has three teeth (T)

|

||

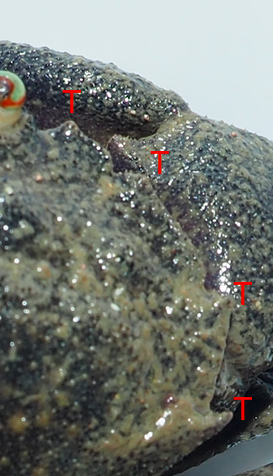

| Antero-lateral margin (sides of the carapace facing the front) |

- thin and sharp - rugose (wrinkled) - covered with four rather distant teeth (T) - first three teeth (nearer to the front) are relatively broad and the last teeth is narrow

|

||

| Chelipeds (pincers, pereopod 1) |

- massive - both of unequal sizes with one a little larger than the other - curved carpus - short and stout black fingers - covered with tiny granules |

||

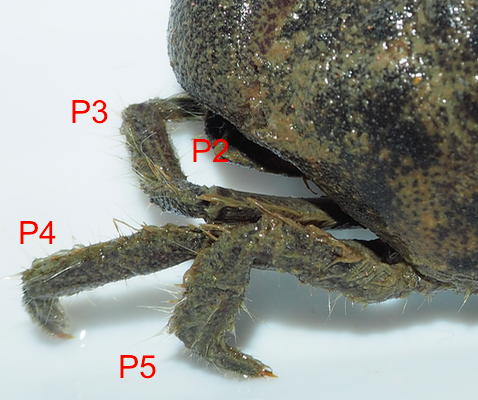

| Walking legs (pereopods 2-5 or P2-P5) |

- rough surface - slender - upper border of last four joints and the lower border of last two joints are abundantly fringed with fine stiff setae (hairs)[6]

|

Back to top

Biology

The morphology of the crab usually reflects the biology and behaviours of a crab species. Therefore, a crab biologist will learn how M. hardwickii makes use of its unique physical features in its daily life and for survival purposes.

Feeding and diet

|

| Thunder crab feeding on a jellyfish. Photo by Ria Tan (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0). |

Movement

M. hardwickii is a non-swimming crab as its last pair of pereopods (pereopod 5) is slim and not designed like a broad paddle shape to swim like other swimming crabs. In addition, it moves or walks rather slowly (personal observation).

Defense mechanism

[Methods to protect the species from predators] |

| Thunder crab playing dead. Photo by Suhailah Isnin. |

Usually, when a rock is lifted up in rocky shores, crabs will scatter around to seek refuge in other hiding crevices. However, unlike other crabs, M. hardwickii will ‘cuddle up’ by tucking its limbs under its body and play dead when predators discover its hiding place (lifting the rocks). Therefore, predators will be fooled by its ‘stone appearance’ camouflage and target other scurrying crabs. In addition, it can resist from being pulled out by predators by pushing its strong chelipeds and bodies against the rock crevices.[2] Furthermore, it will also spread both its chelipeds outwards from its body to threaten to pinch the predator (personal observation).

Back to top

Ecology

[Interactions between species and environment]After learning about its biology, a crab biologist should also know if the crab species' way of life suits for which type of environment and whether they are of any use to people, as well as, if its population numbers are in great danger.

|

| Thunder crab hiding in between rocks. Photo by Ahmad R. Rashid (with permission). |

Habitat

[Type of environment where the species live in]This marine crab species is encountered in a wide range of habitats such as the mangroves, littoral rocky shores, breakwaters, floating fish farms (kelongs), coral rubbles and mussel clumps. M. hardwickii can be found hiding in between crevices such as rocks and woods.[1]

Distribution

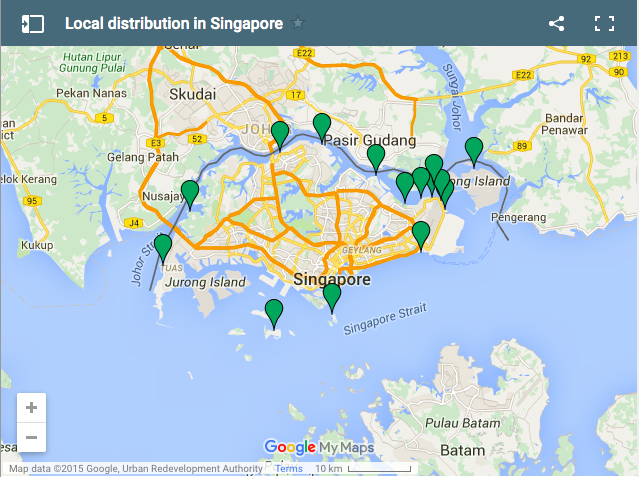

[Location where the species can be found]Singapore

In Singapore, M. hardwickii is mostly populated in the northern part of Singapore where there is fresh water influence from Sungai Johor (Johor River) that is located north-eastern of Singapore. The crab population can also be located in the western and southern side of Singapore too.

Global

M. hardwickii is not endemic to Singapore. Globally, the crab species is mainly distributed on the coasts facing the Indian Ocean and their sightings include the east coast of Africa, Mauritius, east and west coasts of India[9], Taiwan[10, 11] and Southeast Asia such as Singapore, Malaysia[12], Thailand (Phuket)[13], Myanmar (Mergui Archipelago)[9], Indonesia (Sulawesi) and Borneo.[4]

Human uses

Fishermen will pull out their meaty chelae (claws) for food but the crab is rarely eaten as a whole.[12] A study has shown that the mangrove Thunder crab population in Singapore contains heavy metal contaminants such as mercury (Hg), cadmium (Cd), arsenic (As) and chromium (Cr) and lead (Pb) so it is not for human consumption.[14]

Threat status

Currently, M. hardwickii has not been evaluated yet according to International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List and Singapore Red Data Book.[15,16] However, it was reported that the crab population is susceptible to the rising temperature that is caused by the ongoing global warming and climate change.[7] Therefore, its population numbers will be adversely affected if the rate of the rising temperature and sea level does not slow down.

Back to top

Name

Next, a crab biologist may also wonder how the crab species got its name and who first discovered and described the species. Sometimes, the same species can be described several times using different names like in the case of M. hardwickii. For simplicity's sake, common names are also used to describe the species.

Binomial (scientific) name: Myomenippe hardwickii (Gray, 1831)

Vernacular (common) name: Stone crab (English), Mangrove Stone crab (English), Thunder crab (English), Grey-hizumegani (Japanese)

|

| Thunder crab. Photo by Suhailah Isnin. |

Synonyms

[Other scientific names that have been used to describe the same species but are no longer accepted]- Cancer hardwickii Gray, 1831

- Menippe granulosa A. Milne-Edwards, 1867

- Menippe granulosa De Man, 1888

- Menippe duplicidens Hilgendorf, 1878

Etymology

[Origin of the species name]The species epithet of M. hardwickii was named after Major-General Thomas Hardwicke who first discovered and collected the crab species which originated from the Indian Ocean.[3] It was then given to Dr John Edward Gray for description of the species (see original description).

Back to top

Taxonomy

[Science of classifying and naming organisms in an ordered system]A crab biologist should also be familiar with the Linnaean classification system as all living organisms are being grouped according to their similarities using a set of rules. A biologist by the name of Carl Linnaeus started this classification system. He also devised the binomial (two-name) system to describe the species which consists of a genus (a group of related species) and a species epithet. The first letter of the first name which is the genus is capitalised and both the genus and species are italicised as described below.

Taxonavigation

[Classification of the species]Kingdom: Animalia Linnaeus, 1758

Phylum: Arthropoda Latreille, 1829

Subphylum: Crustacea Brünnich, 1772

Class: Malacostraca Latreille, 1802

Order: Decapoda Latreille, 1802

Family: Menippidae Ortmann, 1893

Genus: Myomenippe Hilgendorf, 1879

Species: Myomenippe hardwickii (Gray, 1831)

Taxonomic history

[History of the classification and naming of the species]M. hardwickii was originally described as Cancer hardwickii by Dr John Edward Gray in 1831.[3]

Back to top

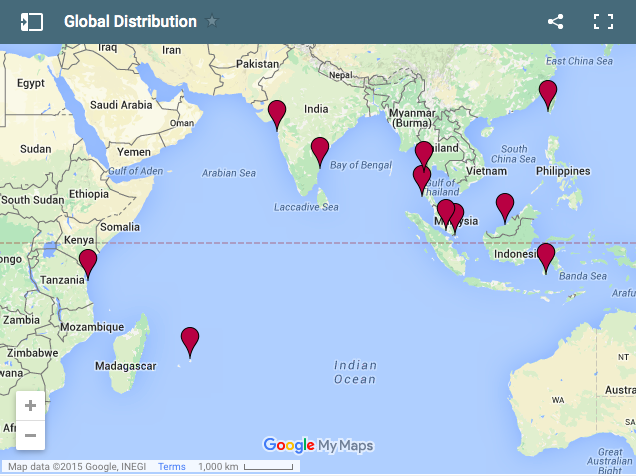

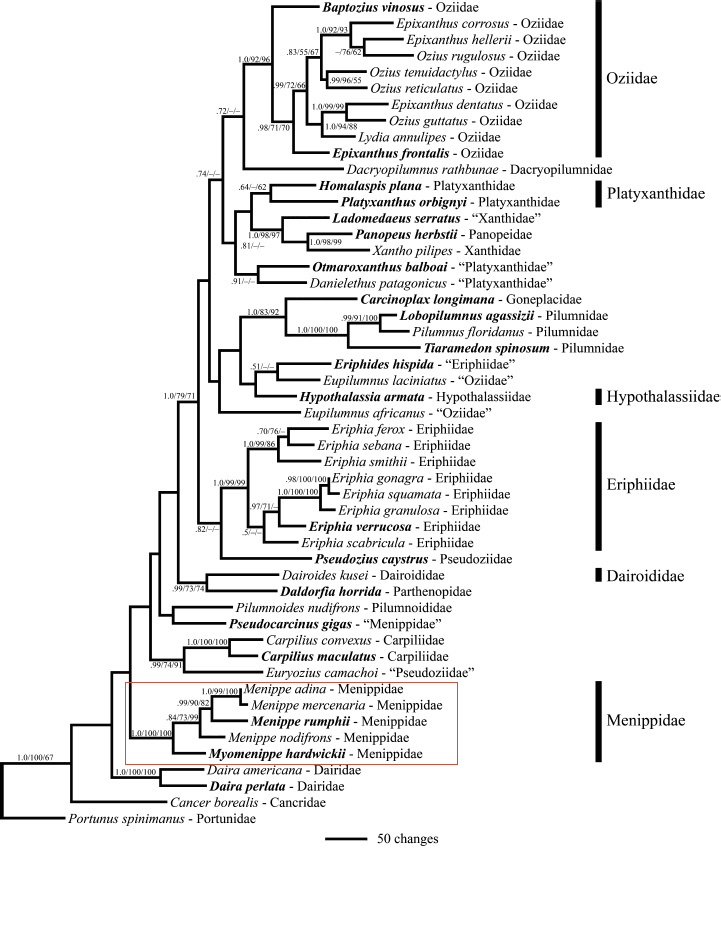

Phylogeny

[Evolutionary history and relationship of the species]After learning the classification of M. hardwickii, a crab biologist may also be curious to find out if the crab species has other closely related species and share common ancestor with other crab species.

To demonstrate the evolutionary process of a certain species, a phylogenetic tree is usually constructed based on either genetic or physical characteristics. The tree is important for biologists to understand the evolution of the species through time and identify closely-related species. The tree which depicts the phylogenetic position of M. hardwickii is shown below (in a red box) and it is constructed based on genetic characteristics - three mitochondrial (12S, 16S and COI) and two nuclear genes (18S and Histone 3). The phylogenetic tree below demonstrates that the genus Myomenippe is sister group (derived from a common ancestor) to the genus Menippe, which includes the species Menippe adina, Menippe mercenaria, Menippe nodifrons and Menippe rumphii.[17]

|

| Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of Eriphioid crabs with posterior probabilities/ML bootstrap/MP jackknife support. Taxa in bold indicates type species of genus. Family names (right side of figure) following species names represent current classification. Phylogenetic position of family Menippidae crab in a red box. Adapted from Lai et al., 2014 (with permission). |

Back to top

Type information

[Information on the specimen that was used to first describe the species]Finally, a crab biologist should also know that type information is important for taxonomists to refer back to when describing the species.

The type locality (location where species was first discovered) of the holotype (specimen that was used to first describe the species) originated from the Indian Ocean and was discovered by Major-General Thomas Hardwicke. The holotype was deposited in the British Museum, London.[3]

Back to top

Links to other online sources

Click on these links to find out more about the Thunder crab!

- Encyclopedia of Life (eoL)

- GenBank

- Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF)

- Guide to the Mangroves of Singapore

- Marine Species Identification Portal

- National Institute of Oceanography

- SeaLifeBase

- The Tide Chaser

- WildSingapore

- World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS)

Back to top

Literature cited

1. Ng, P.K.L., et al., Singapore Biodiversity: An Encyclopedia of the Natural Environment and Sustainable Development. 2011: Editions Didier Millet.

2. Ng, P.K.L., L.K. Wang, and K.K.P. Lim, Private lives--an exposÈ of Singapore's Mangroves. 2008, [Singapore]: Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research, Dept. of Biological Sciences, National University of Singapore.

3. Gray, J., Description of a new genus, and some undescribed species of Crustacea. Zoological Miscellany, 1831. 1: p. 39-40.

4. Man, d.J., Zoological Results of the Dutch Scientific Expedition to Central Borneo. Notes from the Leyden Museum, 1899. 21(1/3): p. 53-144.

5. Tan, M.H., et al., The complete mitogenome of the stone crab Myomenippe fornasinii (Bianconi, 1851)(Crustacea: Decapoda: Menippidae). Mitochondrial DNA, 2014(0): p. 1-2.

6. Alcock, A., The family Xanthidae: the Brachyura Cyclometopa, Pt. I, Material for a carcinological fauna of India, No. 3. Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, 1898. 67(11): p. 1.

7. Nguyen, K.D.T., et al., Upper temperature limits of tropical marine ectotherms: global warming implications. PLoS One, 2011. 6(12): p. e29340-e29340.

8. Han, L., et al., The defensive role of scutes in juvenile fluted giant clams (Tridacna squamosa). Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 2008. 359(1): p. 77-83.

9. Chhapgar, B., On the marine crabs (Decapoda: Brachyura) of Bombay state. J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc, 1957. 54(2): p. 399-439.

10. Ng, P.K., et al., An annotated checklist of brachyuran crabs from Taiwan (Crustacea: Decapoda). 2001: National Taiwan Museum.

11. Lai, S., I. Huang, and L. Fang, Crab fauna of Kaohsiung Harbor, southwestern Taiwan. Ann. Taiwan Mus, 1997. 40: p. 225-240.

12. Tan, C.G. and P.K. Ng, An annotated checklist of mangrove brachyuran crabs from Malaysia and Singapore. Hydrobiologia, 1994. 285(1-3): p. 75-84.

13. Ng, P.K. and P.J. Davie, A checklist of the brachyuran crabs of Phuket and western Thailand. Phuket Marine Biological Center Special Publication, 2002. 23(2): p. 369-384.

14. Cuong, D.T., et al., Heavy metal contamination in mangrove habitats of Singapore. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 2005. 50(12): p. 1732-1738.

15. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (2015). Myomenippe hardwickii. Retrieved from http://www.iucnredlist.org/search.

16. Davison, G.W., P.K. Ng, and H.C. Ho, The Singapore red data book: Threatened plants & animals of Singapore. 2008: Nature Society.

17. Lai, J.C., et al., Phylogeny of eriphioid crabs (Brachyura, Eriphioidea) inferred from molecular and morphological studies. Zoologica Scripta, 2014. 43(1): p. 52-64.

Back to top