Table of Contents

1. Eurasian Curlew?

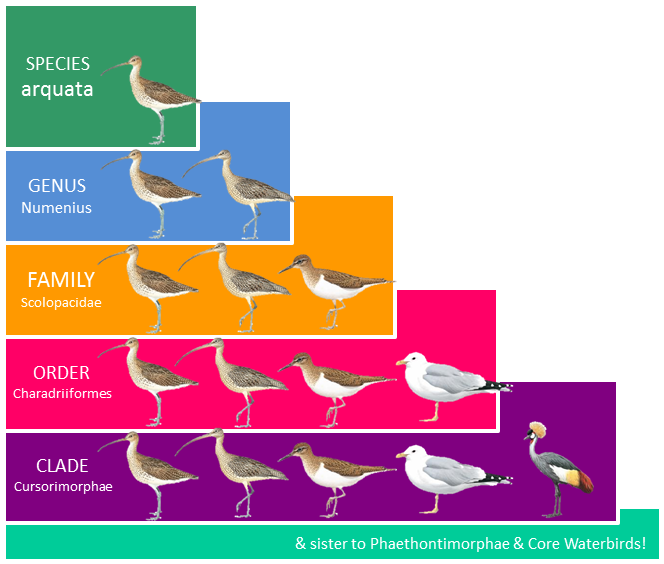

The Eurasian curlew Numenius arquata (Linnaeus, 1758) is a uncommon winter visitor to Singapore that can be spotted from August to March at shores and estuaries. It is a large member of the diverse avian family Scolopacidae - which also contains the sandpipers and other shorebirds (remember Disney's Piper ?). Sporting a long, downcurved bill, the Eurasian curlew has an overall mottled brown plumage with pale underparts (Fig. 1). The Eurasian curlew ranges from North-western Europe and extending into Siberia and undertakes yearly migrations to coasts of Africa through to Southeast Asia. The Eurasian curlew has three recognised sub-species: N. a. arquata (Linnaeus, 1758), N. a. suschkini (Brehm, 1831), N. a. orientalis (Neumann, 1929). While we only get the N. a. orientalis[1] subspecies in Singapore, the largest of the three subspecies, information and pictures depicted in this page are of the species in general. This is because differences amongst the subspecies are mainly in their ranges while differences in appearance is slight and variations within subspecies overlaps with one another. Information about its biology and threats is generalisable to the species. Read on to find out the life of this uncommon bird, and maybe even plan a trip to Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve to see the Eurasian Curlew. You may also find it easier to navigate to your area of interest with the panel on the right. Happy reading!2. What's in a name?

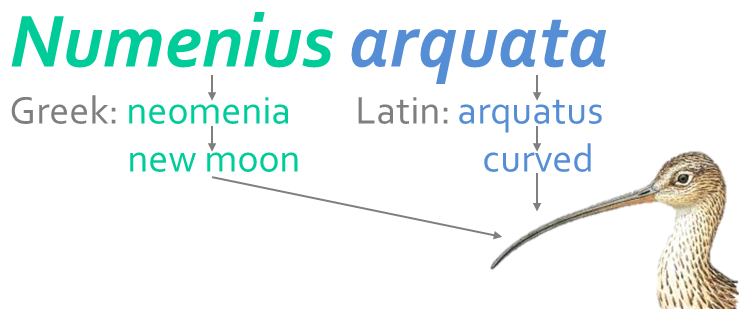

The genus name, Numenius, is derived from the Greek word neomenia, which means new moon (“neo” meaning new and “menia” meaning moon) and is thought to refer to the crescent shape of the bills of birds in this genus. The name is also associated with noumēnios, the curlew-like bird mentioned by Hesychius in ancient Greek. The species name, arquata, is derived from the Latin word arquatus, which means bow-shaped or curved. This is likely a reference to the bill of the Eurasian curlew being bent like a bow.

The sub-species name, orientalis, originated from the Latin word meaning eastern and refers to the eastern sub-species of Eurasian curlews[2] . The remaining sub-species,suschkini, was named after Petr Petrovich Sushkin, a Russian ornithologist (cite). The name 'curlew' (and this applies to all birds in the genus Numenius) resembles the curlew's call which is described as “cour-li”[3] . It may also have been influenced by the Old French courlieu or “courier” or “to run”[4] . Its vernacular name Eurasian Curlew likely refers to the known breeding range of N. arquata across Europe and Asia.

3. Where can it be found?

a. Occurrence in Singapore

In Singapore, the Eurasian Curlew is considered an uncommon visitor in the migration season. It may either stay on for the entire winter or stop briefly to refuel before moving further south via the East Asian-Australasian Flyway[5] . This makes Sungei Buloh (Fig. 2) an important site on this flyway as it provides feeding and resting grounds for the Eurasian Curlew and many other migratory birds[6] . The earliest records of Eurasian Curlews arriving in Singapore is as early as 24th August and the last of them stayed until as late as 22nd March. Past records (Fig. 3) include Changi Cove, Khatib Bongsu, Lorong Halus, Pulau Busing, Pulau Hantu, Pulau Sakeng, Pulau Sudong, Pulau Ubin, Punggol, Seletar, St John's Island, Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve and Tanah Merah[7] . In 2016, its first arrival was recorded on the 5th of August on Pulau Tekong. Later on, two individuals also arrived at Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve on the 25th of August[8] .

Figure 2. A view of the mangroves from one of the observation hides, Photo by Calvin Teo, CC3.0

Figure 3. Past sightings of the Eurasian Curlew in Singapore

b. Habitat

During the winter the species frequents muddy coasts, bays and estuaries with tidal mudflats and sandflats, rocky and sandy beaches with many pools, mangroves, saltmarshes, coastal meadows and muddy shores of coastal lagoons, shores of inland lakes and rivers [9] [10] [11] . It also utilises wet grassland and arable fields during migration[12] . This explains its coastal distribution across Singapore where suitable habitat can be found.In the breeding months of April to July, the Eurasian Curlew inhabits upland moors (Fig. 4), peat bogs, swampy and dry heathlands, fens, open grassy or boggy areas in forests, damp grasslands, meadows, non-intensive farmland in river valleys[13] , dune valleys and coastal marshlands[14] .

Figure 4. Oswaldtwistle Moor, part of the West Pinnie Moors, in Lancashire UK, Photo by Orphan Wiki, CC3.0

c. Distribution across the globe

Figure 5. Range of the Eurasian Curlew, from IUCN

The Eurasian Curlew occurs in a wide range across most of the Palearctic and is naturally occurring in about 150 countries. It breeds (yellow areas on Fig. 5) from the British Isles across to north-western Europe and Scandinavia into Russia and extends to the east as far as Siberia, east of Lake Baikal. Its wintering range (blue areas on Fig. 5) includes the coasts of north-western Europe, Mediterranean, Africa, South and East Asia and the Sundas. Past records of vagrancy included countries like Greenland, Canada and the Bahamas[15] .

The 3 subspecies, N. a. arquata, N. a. suschkini and N. a. orientalis, occupies the western, central and eastern portion of the Eurasian Curlew's breeding range (Table 1) respectively. Areas where overlap occurs is not well defined.

Table 1. Distribution of the 3 subspecies of the Eurasian Curlew

| Subspecies |

Distribution |

| N. a. arquata (Linnaeus, 1758) |

Breeds from British Is and France across W Europe (N to Arctic Circle) and E to R Volga and Urals; Winters from Iceland and British Is S to Mediterranean and NW Africa, and E to Persian Gulf and W India. |

| N. a. suschkini Neumann, 1929 |

Breeds from lower R Volga and Urals E to SW Siberia and N Kazakhstan; Winters along coasts of sub-Saharan Africa and SW Asia. |

| N. a. orientalis C. L. Brehm, 1831 |

Breeds from C Siberia E through C Russia to NE China (C Heilongjiang); Winters in E & S Africa, Madagascar, and from S Caspian Sea S to Persian Gulf and E through S Asia to E China and S Japan, and S to Philippines and Greater Sundas. |

4. How do we recognise it?

a. Diagnostic features

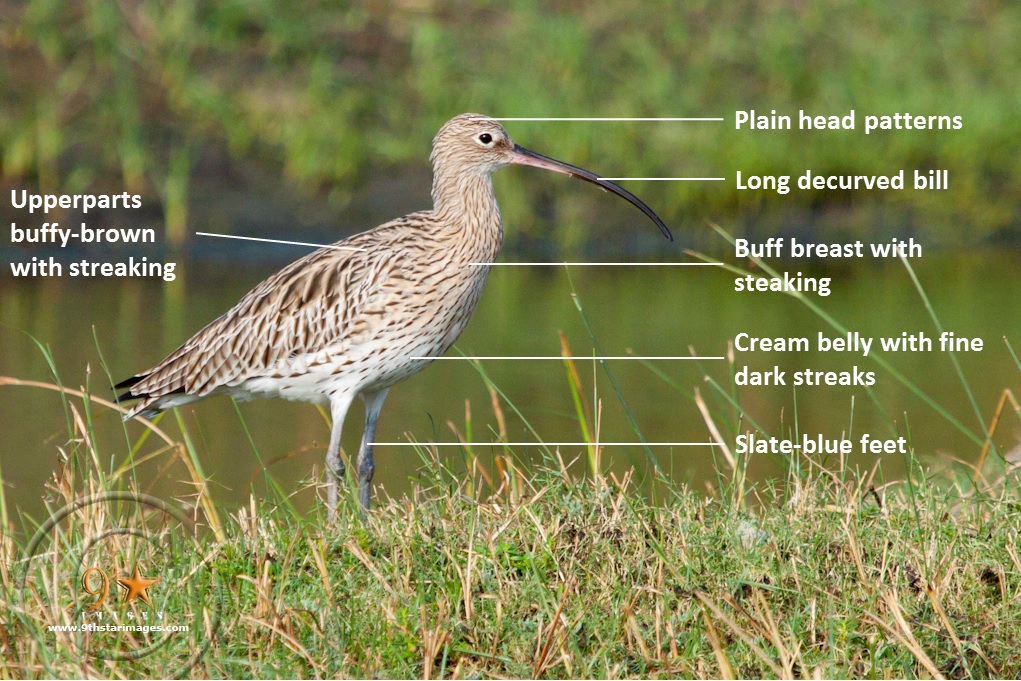

For the description of features of the Eurasian Curlew, do refer to the labelled bird anatomy pictures (Fig. 7)[16] if needed. A more interactive experience can also be found at All About Birds by The Cornell Lab.

Figure 7. Anatomy of a shorebird (a) standing and (b) in flight

i. Appearance

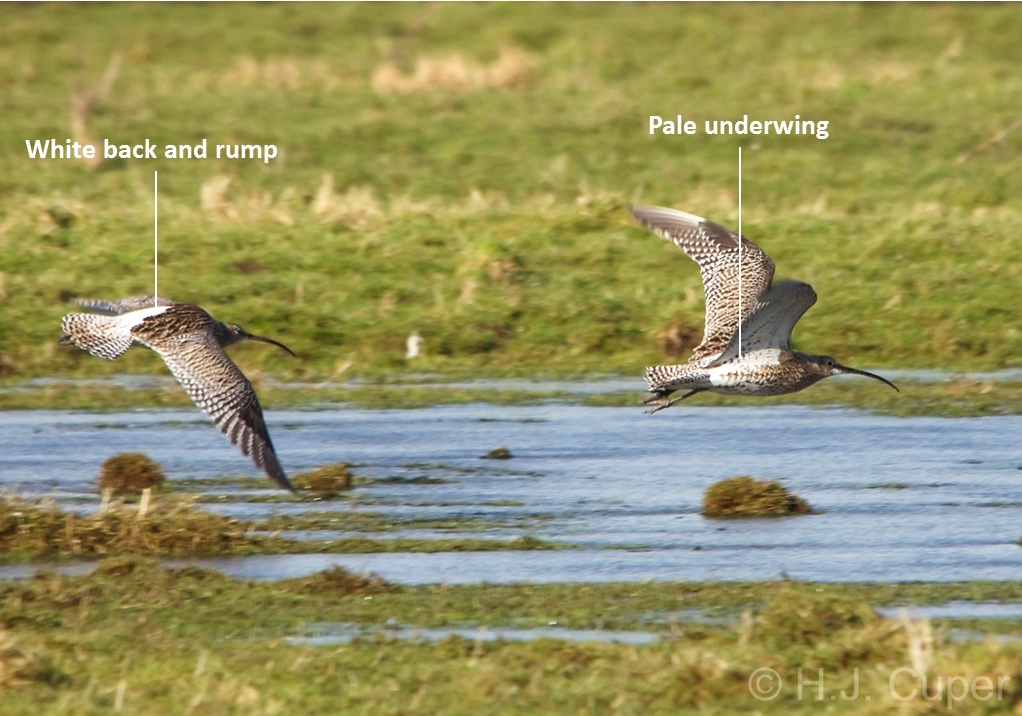

The Eurasian Curlew is a large-sized wader of 50-60cm with a wingspan of 80-100cm. Its diagnostic features (Fig. 6) include a plain head pattern with lack of distinct stripes. A long decurved bill and slate-blue feed. It has a striking white rump and back as well as pale underwings. Overall plumage is buffy-brown with streaking on the upperparts, buff breast with streaking and cream belly with fine dark streaking on the lowerparts. More details of the anatomy of the bird is displayed in table 2. Juveniles are similar in appearance to adults except with buffer breast and fewer streaking on the flanks[17] . Fledglings have short bills and may be mistaken for the Slender-billed Curlew or Whimbrel[18] . Breeding and non-breeding plumages are similar, with the latter being duller in colour[19] . Sexes are alike in plumage but females are on average larger. Interestingly, the differences in bill size and length amongst the sexes has created sexual differences in foraging methods.Table 2. General descriptive features of Eurasian Curlews[20] [21][22]

| Body Part |

Description |

| Head |

|

| Iris |

|

| Bill |

|

| Neck |

|

| Upperparts |

|

| Underparts |

|

| Wing |

|

| Lower rump |

|

| Tail |

|

| Leg & feet |

ii. Call

The primary call of the Eurasian Curlew is a ringing "COURli ... COURli ... COURli" that can be heard all year round. This call can be used for warning, contact and excitement. Variation exists in the inclusion of a loud rapid "ui-cui-cui-cui".main call & variation

The Eurasian Curlew also has three other calls that are used in territorial advertisement namely: a low, drawn-out whistle "whaup", a mellow bubbling call "k-r-r-r-li" and a high intensity bubbling call that sounds like a combination of the first two territorial vocalisations "whaup" followed by "k-r-r-r-li" followed by "curLEE-curLEE-curLEE-curLEE" and sometimes ending with "whaup". Both sexes are known to emit these calls[23] . Click here to listen to more vocalisations of the Eurasian Curlew.

b. Similar species

The Eurasian Curlew can be confused with other members of its genus like the Far-Eastern Curlew (Numenius madagascariensis)[24] [25] and the Whimbrel (Numenius phaeopus)[26] [27] due to their similar grey-brown and streaked plumage. All three birds are winter migrants to Singapore with similar, overlapping habitat distributions. Wimbrels are common winter visitors to Singapore and have been sighted yearly, with some individuals staying over (first years staying behind) throughout the year. Therefore, if a similar-looking bird is sighted in non-winter months, its identity if likely the Whimbrel and not the Eurasian Curlew. On the other hand, the Far-Eastern Curlew is very rarely sighted, with the last sighting being in May 2008[28] . The size of the bird, bill morphology, head patterns, rump and underwing colour are important distinguishing features in the field.| Species |

Head & bill |

Rump |

Underwing |

| Eurasian Curlew (Numenius arquata) 50-60cm |

|

|

|

| Far-Eastern Curlew (Numenius madagascariensis) 53-66cm |

|

|

|

| Whimbrel (Numeius phaeopus) 40-46cm |

|

|

|

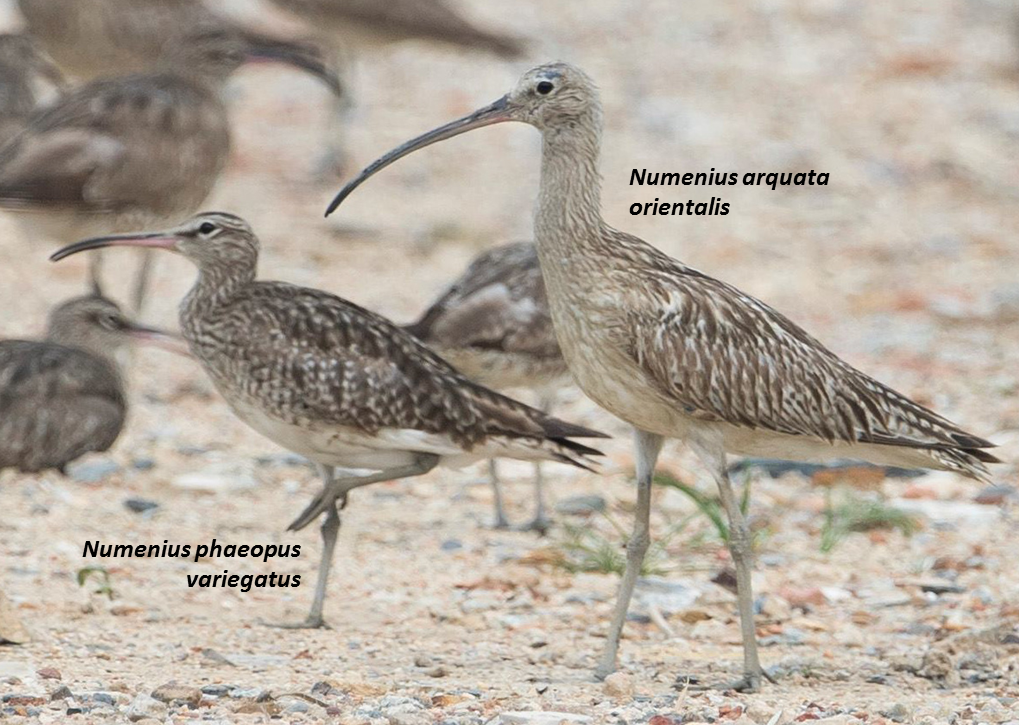

The following photo, figure 8, was taken in September 2016 at Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve and shows the Eurasian Curlew (right) and the Whimbrel (left) side by side. Note the diagnostic differences in body size, head patterns and bill length (Eurasian Curlew is larger, has plain head patterns and a distinctly longer bill).

Figure 8: Photo by See Toh Yew Wai (Permission granted).

c. Variation between the subspecies

A clinal morphological variation amongst the different subspecies can be observed across the breeding range, which corresponds to the delimitation of the 3 subspecies. Accurate identification of subspecies in the field based on morphology alone may be challenging.

| Subspecies |

Comparison to N. a. arquata |

||

| Size |

Underwing and axillaries |

Lower rump and tail |

|

| N. a. suschkini |

similar |

largely unmarked |

rump more barred, tail with black and white bars |

| N. a. orientalis |

larger |

largely unmarked |

rump more barred, tail with brown and white bars |

5. What does it do?

a. Behaviour and social interactions

The Eurasian Curlew can frequently be seen near the shores, marshes and estuaries of wetlands, using their long, decurved beaks to forage for food in the mud. From breeding pairs to aggregations of thousands of individuals, the Eurasian Curlew can be engaged in a variety of social interactions. Most populations are fully migratory[29] . It make also form mixed flocks with other members of the genus Numenius such as in figure 9. The formation of mixed flocks is hypothesised to benefit the birds as less vigilance is required by individuals and feeding success is improved[30] . Figure 9. Eurasian Curlew in flight with Whimbrels. Note the striking white rump. Photo by Seng Alvin (Permission granted).

Figure 9. Eurasian Curlew in flight with Whimbrels. Note the striking white rump. Photo by Seng Alvin (Permission granted).b. Feeding

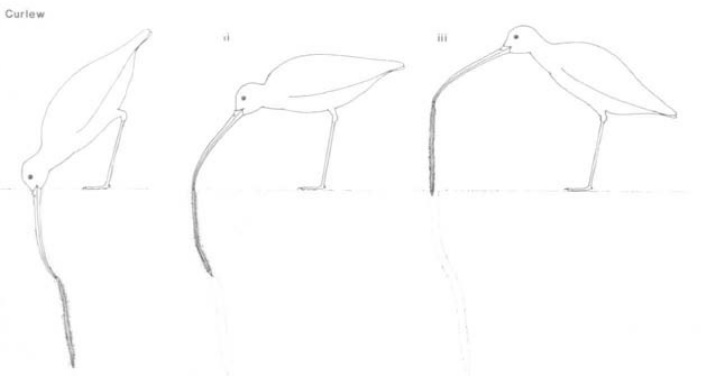

Figure 10: Techniques used by a Eurasian Curlew to pull a worm from the mud (Davidson et al., 1986, p. 63)[31]

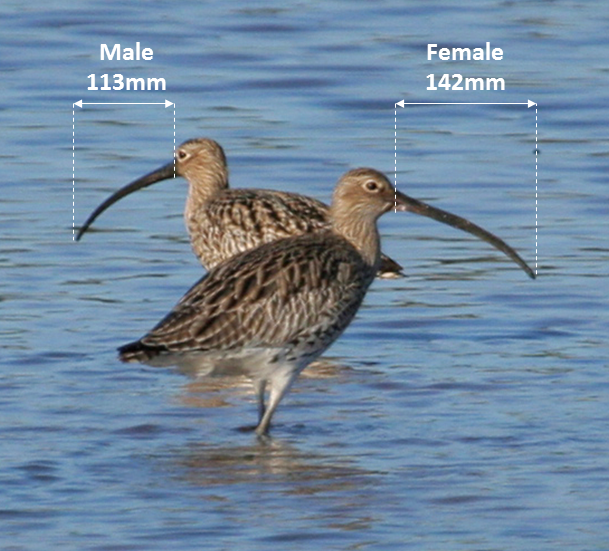

Figure 10: Techniques used by a Eurasian Curlew to pull a worm from the mud (Davidson et al., 1986, p. 63)[31] The Eurasian Curlew's diet consists mainly of worms and terrestrial insects like beetles and grasshoppers. It also preys on a variety of organisms like crustaceans, molluscs, polychaete worms, spiders and even berries and seeds. It can also feed on small fish, amphibians, lizards, small rodents and even young birds on occasion. Using its long bill, the Eurasian Curlew feeds by pecking, jabbing or probing deep into the substrate to search for prey. In the video, you can see the Eurasian Curlew foraging at Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve (video by Adrian Gopal) and rinsing the prey in the water before consumption. Peak foraging timing occurs 4-9 hours after high tide[32] . The bills of birds are important determinants of a bird's ability to locate and capture prey. In the Eurasian Curlew, the average bill length of the male and the female are 113mm and 142mm respectively (Fig. 11), allowing the males better control in rotation and the females the ability to reach deeper into the substrate[33] . As a result, males show a preference for foraging for earthworms (Lumbricids) on cultivated grasslands while females show a preference for foraging in intertidal mudflats for molluscs, crabs, and polychaete worms[34] . When both genders occur on the intertidal flats, males and females differed in their preferred prey, with males favouring shore crabs while females favoured bivalves[35] .

Figure 11. Eurasian Curlew (w/ Sounds), Photo by Muchaxo, CC2.0

c. Reproduction

Eurasian Curlews are winter visitors to Singapore and do not breed here. They have only one partner during each mating season from April to July and may bond with the same partner over a few years. They may also visit the same breeding site over a few years. At each breeding site, high densities of breeding pairs may be observed, where males will show greater vigilance in territorial defence[36] . Males are also responsible for constructing nests by lining large depressions with dry grass or feathers[37] . Nests are usually constructed in open areas with grass cover[38] . Typically, four brown and grey speckled olive coloured eggs (Fig. 12) will be laid by the female and incubation takes between 26-30 days. Hatchlings will be cared for by both parents and fledge within 32-38 days[39] . Anomaly reproduction situations have been observed, such as one individual mating with more than one bird of the opposite sex (i.e. having more than one partner during one season), or the usage of one nest by two female to lay eggs[40] .

Figure 12. Clutch of eggs, Photo by Polarit Commonswiki, CC3.0

d. Migration

Most populations of the Eurasian Curlews are undertake yearly journeys between breeding and wintering sites each year. They begin their migration down South starting in June, with adult females and non-breeders leaving the breeding grounds first. The return back to breeding grounds begins as early as February but most individuals will migrate between March and April. Many Eurasian Curlews that are in their first year of age remain in wintering grounds for that year and do not return to breeding grounds. Resident, non-migratory populations can be found in the British Isle and Ireland .

Figure 13: Migration routes of three adult and one immature Curlews caught in the eastern German Wadden Sea. Different colors represent different individuals. Black circles indicate the location of the potential breeding site (Schwemmer et al., 2016, p. 902)

6. How many of them are there?

a. Population and IUCN conservation status

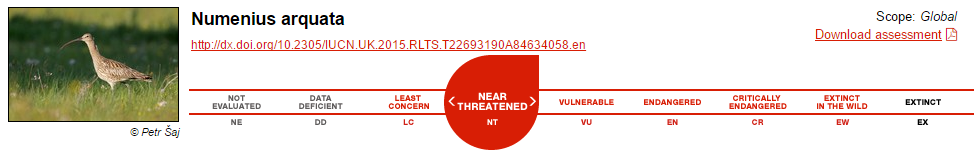

IUCN status: Near Threatened since 2008

While the Eurasian Curlew can be found over a large range, declines in major populations and a general declining trend worldwide is observed. It is estimated that a moderately rapid worldwide decline in population numbers can be expected[41] . The global population estimate for the Eurasian Curlew is placed at 765,000 - 1,065,000[42]

Subspecies population estimates[43] are:

| Subspecies |

Population size worldwide |

| N. a. aquata |

700,000-1,000,000 |

| N. a. suschkini |

1-10,000 |

| N. a. orientalis |

10,000-100,000 |

|

| Numenius arquata |

|

| Numenius arquata |

Figure 14: The Eurasian Curlew has been featured on the stamps of countries within its range (a) Numenius arquata by VLIZ Collection, CC4.0 and (b) Collection Georges Declercq, CC4.0

b. Threats

In breeding grounds, lost of breeding habitat and increased offspring mortality are significant challenges. Due to conversion of land to intensive agriculture, the Eurasian Curlew is threatened by the loss and fragmentation of breeding habitats[47] [48] . Interestingly, the suschkini subspecies is facing the opposite problem, where the grasses in abandoned agriculture land become too high for nesting[49] . In both cases, the Eurasian Curlew faces increasing mortality of eggs and hatchlings due to predation and farming practices[50] .In non-breeding sites, the Eurasian Curlew also faces habitat destruction from development and the habitat alterations that follows. Feeding intertidal grounds may also be lost as more and more hydro management practices are applied worldwide[51] . Hunting, pollution and human disturbances are also part of the largely

anthropogenic threats faced by the Eurasian Curlew.

c. Conservation Actions

A management plan for the Eurasian Curlew was published for the EU porition of its range in 2007, outlining key conservation targets in protecting key habitats, determining the threats to the species and continued monitorinng[52] . A 5 year moratorium on hunting the species was implemented in France in July 2008 (A. Duncan in litt. 2008). The species occurs in a large number of protected areas throughout its range and features in several national monitoring schemes[53] .7. When was it described?

Scientific name: Numenius arquataVernacular name: Eurasian Curlew

Synonyms: Scolopax arquata

Taxonomic hierarchy:

| Kingdom |

Animalia |

| Phylum |

Chordata |

| Class |

Aves |

| Subclass |

Neornithes |

| Infraclass |

Neognathae |

| Superorder |

Neoaves |

| Order |

Charadriiformes |

| Suborders |

Scolopaci |

| Family |

Scolopacidae |

| Genus |

Numenius |

| Species |

N. arquata |

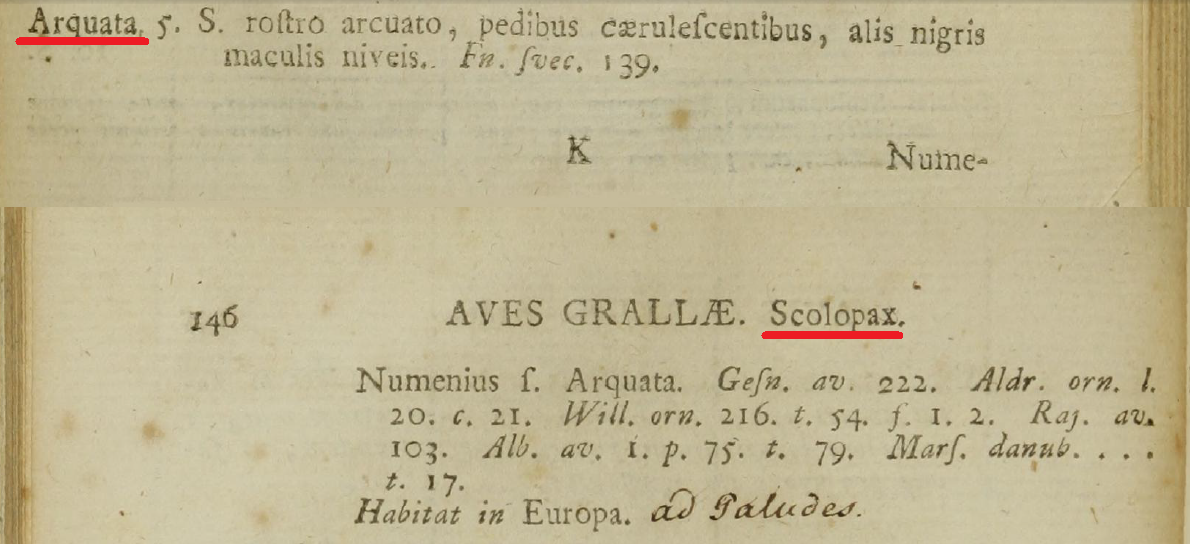

a. Original description

The Eurasian Curlew was first described by Carl Linnaeus in 1758 in the 10th edition of Systema Naturae and was designated as a member of the genus Scolopax[54] .It was later moved to the genus Numenius [55] .

b. Type specimen

The type specimen of the Eurasian Curlew was collected in Sweden[56] . Information on where the type specimen has been deposited is currently not available. The specimen is also the name-bearing type for the genus Numenius[57] .c. Taxonomic revisions

The genus Numenius is a senior synonym to Palnumenius, Miller, 1942. The latter synonym originated when a fossil of a complete left tarsometatarsus from San Josecito Cave in Mexico was erroneously described as an extinct curlew Palnumenius victima[58] . Subsequent examinations revealed that the specimen was not generically separable from the extant genus Numenius and similar to the long-billed curlew Numenius americanus[59] . The genus Palnumenius is retained as a tentative junior synonym to Numenius//.

c. Subspecies descriptions

Three subspecies are recognised for the Eurasian Curlew| Subspecies |

Validity |

Remarks |

| N. a. arquata (Linnaeus, 1758) |

Valid |

This is the nominal subspecies |

| N. a. suschkini Brehm, 1831 [60] |

Valid |

This subspecies is sometimes spelt as 'sushkini' and considered by some to be a synonym of orientalis despite distinct differences. Type specimen of N. a. suschkini was collected from Senegal, Africa and is now deposited in the Field Museum of Natural History (Zoology) Bird Collection |

| N. a. orientalis Neumann, 1929[61] |

Valid |

- |

8. Who is it related to?

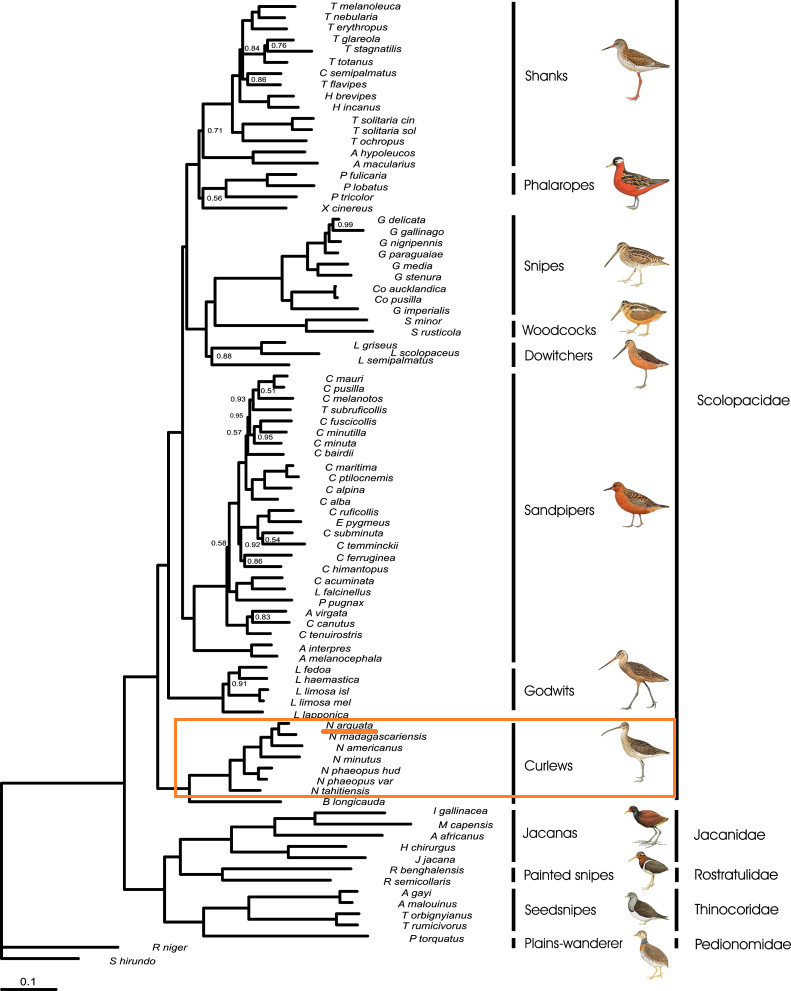

The large amount of diversity in morphology and ecological habitats amongst the Order Charadriiformes (waders) was of interest to many researchers.The most comprehensive study done with regards to the phylogeny of the Eurasian Curlew with other members of its genus was published in 2012[62] . In this study, the phylogeny of the Eurasian Curlew and 83 other members of the Scolopacidae family were constructed with five genes (one nuclear: recombination-activating gene 1 (RAG1) and four mitochondrial: cytochrome b (CYT B), 12S, NADH dehydrogenase subunit 2 (ND2) and cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (COI)) where previous studies based their conclusions on single genes. A partitioned dataset of 6365 aligned base pairs were used for Bayesian analysis, later forming 50% majority-rule consensus trees. It was found, concurring with previous studies, that Numenius was one of the first few genus diverged from the common ancestor of all Scolopaci. Similar to previous studies using character states, the Eurasian Curlew is one of (if not) the most derived species amongst Numenius and is here sister to the Far-Easterm Curlew, which as described in the previous sections to be frequently confused with the Eurasian Curlew. The strengths of the study included that it drew on more genes for the reconstruction of the phylogeny of the Eurasian Curlew and allies, including both nuclear and mitochondrial genes to reflect both slow and fast evolving genes to detect significant differences amongst deeply and newly diverged species respectively. The nodes of branches leading to the Eurasian Curlew and branches within the genus all received a posterior probabilty of 1.00. However, it is noted that the optimality criteria of Bayesian inference may have resulted in the high node support observed in the study. The assumption that prior probabilities on the relationship amongst species is unknown is inaccurate as information about their phylogeny can be retrieved from previous studies using morphology or single genes. Also, the sequence alignment for this study was done by eye and is likely not replicable by other scientists.

Figure 15. Phylogeny based on sequences of five genes (RAG1, CYT B, 12S, ND2, and COI) estimated with partitioned Bayesian analysis for 84 species of the Scolopaci. All nodes received a posterior probability of 1.00 unless otherwise labeled from Gibson & Baker, 2012

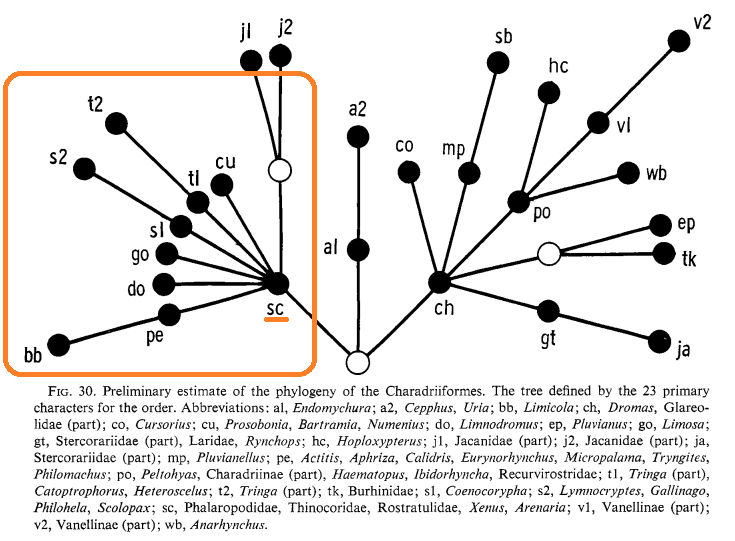

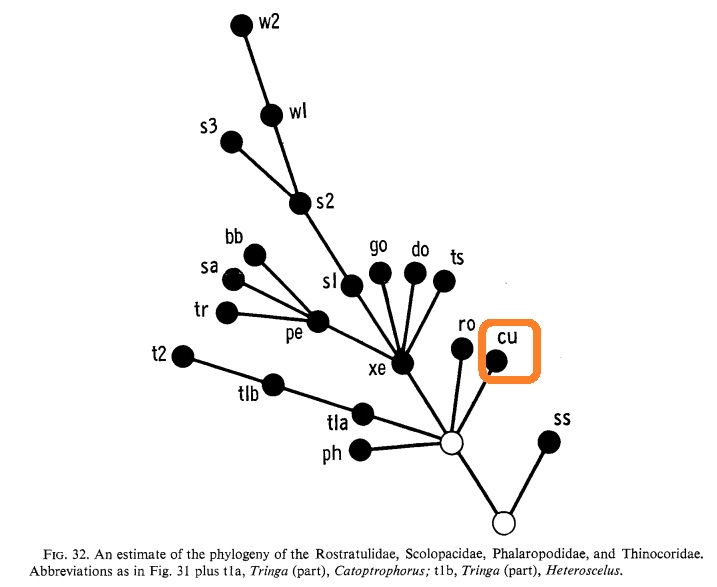

As a clade, the Charadriiformes likely evolved around 65 million years ago at the end of the Cretaceous. In 1978, the phylogeny within the Charadriiformes was first explored using a matrix of 70 charactera states, like the position of the lacrimal-ectethmoid complex, for 227 species of birds . The curlews (Numenius) was demonstrated to be one of the earliest lineages to diverge from the common ancestor of Scolopacidae, which forms one of three main divergence within the Charadriiformes. A reanalysis of the same dataset was conducted by recoding the character matrix and deriving the shortest tree using parsimony, resolving some of the polytomy present in the previous study. In this study, the relationship of the Eurasian Curlew to other Numenius species is first elucidated and is found to be most closely related to N. americanus, a large Nearctic curlew species with a similarly long bill but sporting a dark coloured rump. However, note that the Far-Eastern Curlew was not included in this study.

Figure 16. Estimates of phylogeny of the (a) Charadriiformes and (b) Scolopaci from Joseph & Strauch, 1978 Figure 12. Strict consensus of 2,500 shortest trees found from Chu, 1995

As genetic technology become more prominent and accessible, it is increasingly possible to sequence larger stretches of the genome for phylogenetic analyses. A study of the genus Numenius is underway to investigate the phylogeny of members of this species by tapping on next-generation sequencing to sequence restriction site-associated DNA markers that will provide greater information for tree construction.

- ^ Gibson-Hillm C. A. (1950). A checklist of the birds of Singapore island. Bull. Raffles Museum, 21: 132-183.

- ^ Jobling, J. A. (2009). Helm dictionary of scientific bird names. (1st ed.). Christopher Helm Publishers Ltd.

- ^ Mountfort, G., Hollum, P. A. D., & Peterson, R. T. (2001). A Field Guide to the Birds of Britain and Europe. (5th ed.). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- ^ Hughes, H.G.A. (2004). Oxford English Dictionary. (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- ^ Kirby, J.S., Stattersfield, A.J., Butchart, S.H.M., Evans, M.I., Grimmett, R.F.A., Jones, V.R., O’Sullivan, J., Tucker, G.M. & Newton, I. (2008). Key conservation issues for migratory land- and waterbird species on the world’s major flyways. Bird Conservation International, 18: S49-S73.

- ^ Gan, J.T.W.M. & Ramakrishnan, R.K. (2006). Shorebird abundance and diversity in Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve, Singapore. Waterbirds around the world. (Eds.) G.C. Boere, C.A. Galbraith & D.A. Stroud. The Stationery Office, Edinburgh, UK. pp. 343-344.

- ^ Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum. (2016). Numenius arquata. The Digital Nature Archive of Singapore. Retrieved from http://lkcnhm.nus.edu.sg/dna/organisms/details/903

- ^ OwYong, A. (2016) Singapore Bird Report - August 2016. Nature Society (Singapore) Singapore Bird Group. Retrieved from

https://singaporebirdgroup.wordpress.com/2016/09/08/singapore-bird-report-august-2016 - ^ del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., and Sargatal, J. (1996). Handbook of the Birds of the World, vol. 3: Hoatzin to Auks. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona, Spain.

- ^ Johnsgard, P. A. (1981). The plovers, sandpipers and snipes of the world. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, U.S.A. and London.

- ^ Snow, D.W. and Perrins, C.M. (1998). The Birds of the Western Palearctic, Volume 1: Non-Passerines. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- ^ del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., and Sargatal, J. (1996). Handbook of the Birds of the World, vol. 3: Hoatzin to Auks. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona, Spain.

- ^ Hayman, P.; Marchant, J.; Prater, A. J. (1986). Shorebirds. Croom Helm, London.

- ^ del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., and Sargatal, J. (1996). Handbook of the Birds of the World, vol. 3: Hoatzin to Auks. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona, Spain.

- ^ BirdLife International. 2015. Numenius arquata. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015. Retriever from: http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015.RLTS.T22693190A84634058.en.

- ^ Friends of the Great Plains Nature Centre. nd. A Pocket Guide to Great Plains Shorebirds. Available from: http://www.gpnc.org/images/pdf/GPSBPocketGuide.pdf

- ^

del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., and Sargatal, J. (1996). Handbook of the Birds of the World, vol. 3: Hoatzin to Auks. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona, Spain.

del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., and Sargatal, J. (1996). Handbook of the Birds of the World, vol. 3: Hoatzin to Auks. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona, Spain.

BirdLife International. 2015. Numenius madagascariensis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015. Retrieved from: http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-4.RLTS.T22693199A67194768.en on 05 November 2016.

National Parks Board. (2013). Numenius madagascariensis. Flora and Fauna Web. Retrieved from: https://florafaunaweb.nparks.gov.sg/special-pages/animal-detail.aspx?id=539 on 23 November 2016

Currie, D. & Valkama, J. (2000). Population density and the intensity of paternity assurance behaviour in a monogamous wader: the Curlew Numenius arquata. Ibis 142(3): 372–381.

BirdLife International. 2015. Numenius arquata. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015. Retrieved from: http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015.RLTS.T22693190A84634058.en. on 09 November 2016.

Wetlands International (2015). Waterbird Population Estimates. Retrieved from: http://wpe.wetlands.org/.

Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (nd). Birds & Wildlife: Curlew. Retrieved from: https://rspb.org.uk/birds-and-wildlife/bird-and-wildlife-guides/bird-a-z/c/curlew/index.aspx on 23 November 2016.

del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., and Sargatal, J. (1996). Handbook of the Birds of the World, vol. 3: Hoatzin to Auks. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona, Spain.

Roodbergen, M. & van der Werf, B. & Hötker, H. (2012) Revealing the contributions of reproduction and survival to the Europe-wide decline in meadow birds: review and meta-analysis. J. Orn. 153(1): 53–74.

Burton, N. H. K. 2006. The impact of the Cardiff Bay barrage on wintering waterbirds. In: Boere, G.; Galbraith, C., Stroud, D. (ed.), Waterbirds around the world, pp. 805. The Stationary Office, Edinburgh, UK.

Jensen, F. P.; Lutz, M. 2007. Management plan for Curlew (Numenius arquata) 2007-2009. Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, Luxembourg.

Linné, C. (1758). Systemae Naturae, (10th ed.). Stockholm, 1, p. 145.

Brisson, M.J. and Martinet, F.N. (1760). Ornithologia sive Synopsis Methodica sistens Avium Divisionem in Ordines, Sectiones, Genera, Species, Ipsarumque Varietates, (1st ed.). Paris, 5, p. 311

Van Someren, V.G.L. (1935). The Birds of Kenya and Uganda, The East Africa Natural History Society, Vol. 2, Part 5, p. 69.

Goerlich, A. (2011). Species taxon summary arquata Linnaeus, 1758 described in Scolopax//. Retrieved from: http://www.animalbase.uni-goettingen.de/zooweb/servlet/AnimalBase/home/speciestaxon?id=2817

Gibson, R., & Baker, A. (2012). Multiple gene sequences resolve phylogenetic relationships in the shorebird suborder Scolopaci (Aves: Charadriiformes). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 64(1), 66-72.