|

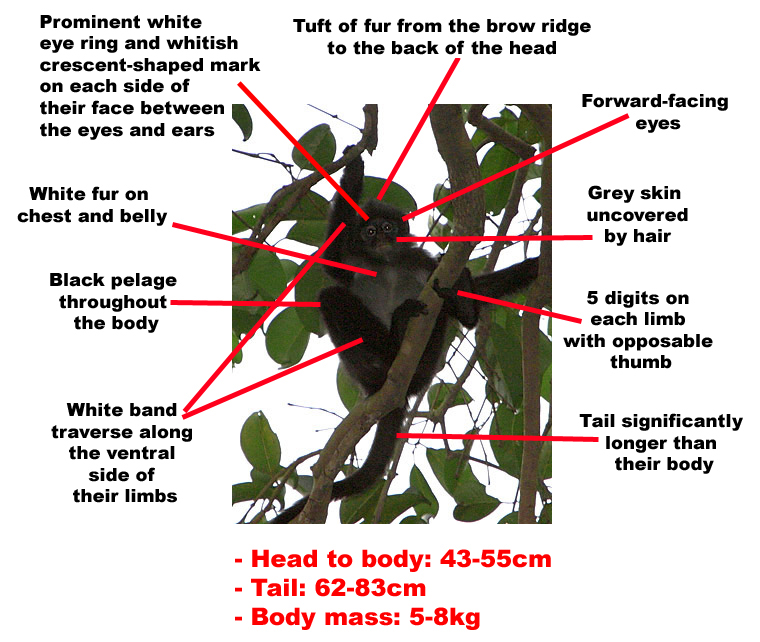

| Figure 1: The banded leaf monkey of Singapore (photo from: Chan Kwok Wai (wildsingapore.per.sg), used with written permission from the author) |

Page Created by: Siow Jer JianLast Updated on: 23rd June 2014

(best viewed with screen resolution of '1366 X 768' or higher)

At a glance!

Table of Contents

|

Click this video here to check out the glance (or rather the stare) of the banded leaf monkey (check them checking you out)!

Video 1: Habituation observation of the banded leaf monkey to the researcher. (footage from Andie Ang, used with written permission from the author)

^ to the top!

1 - Descriptions

| “Tak kenal maka tak cinta” (Don’t know, don’t love) – Malay Proverb |

|

| Figure 2: The banded leaf monkey’s tail is a lot longer than its body. (photo from: Chan Kwok Wai (wildsingapore.per.sg), used with written permission from the author) |

How do they look like?

Click here to listen to the banded leaf monkey’s characteristic clicking call:- According to Andie's research, this is an alert call following severe disturbances [51]. (Audio recording by Linda Chan, used with written permission from Chan Kwok Wai (wildsingapore.per.sg)) (for more info on their calls/vocalization, see "Behaviour") |

It is a species of Asian colobine (subfamily: Colobinae) with black fur as the overall coat cover, white fur on the belly, and white bands/lines traversing the underside (ventral section) of its limbs, particularly on its inner thigh which links to its body (chest to abdomen) [3][4][11]. This pelage colouration probably acts like a counter-shading camouflage in which the white pelage on the ventral side paints out their shadow and obliterate their three dimensional form (unproven speculation).

Adults are usually sized around 43cm to 55cm from the head to the body while their tail alone can reach around 62cm to 83cm [11][23]. The males are on average somewhat larger than the females [23]. The adults weight around 5kg to 8kg [23]. Like most of the members from the order of primates, they have forward-facing (stereoscopic) eyes, no sexual dimorphism (do not occur in two distinct gender form), and five digits on each limb with opposable thumbs [2][12][23][64]. Their hind limbs are longer than their fore limbs [31]. Both their legs and arms are long and slenderly built which is associated with their leaping locomotion (for more info, see "Behaviour") [62]. Since they belong to the Old World Monkeys (family Cercopithecidae; for more info, see "Phylogeny (Evolutionary History)"), they have a non-prehensile (incapable of grasping) tail [64].

The stiff hair on their forehead radiates from one or two centre(s) [23]. The hair that grows backward from the sides of their head comes into conflict at the median (middle) of their head, producing a characteristic erect median ridge or crest [23]. They have prominent white eye ring and whitish crescent-shaped mark on each side of their face between their eyes and ears [63].

In Singapore, they are the largest non-human primate still in existence [2].

The young of many primate species, as with the banded leaf monkey, have distinctively different pelage colouration and pattern from their adults, which was suggested to differentiate the infants that are dependant from the independent adults [1][3]. This may further elicit care and protective response from the older group members which subsequently increases the infants chance of survival [1][26]. For the description of the infants, see “Growth & Development”.

|

| Figure 3: Adult pelage of the banded leaf monkey (photo from Andie Ang, used with written permission from the author) |

1.1 - Diagnosis

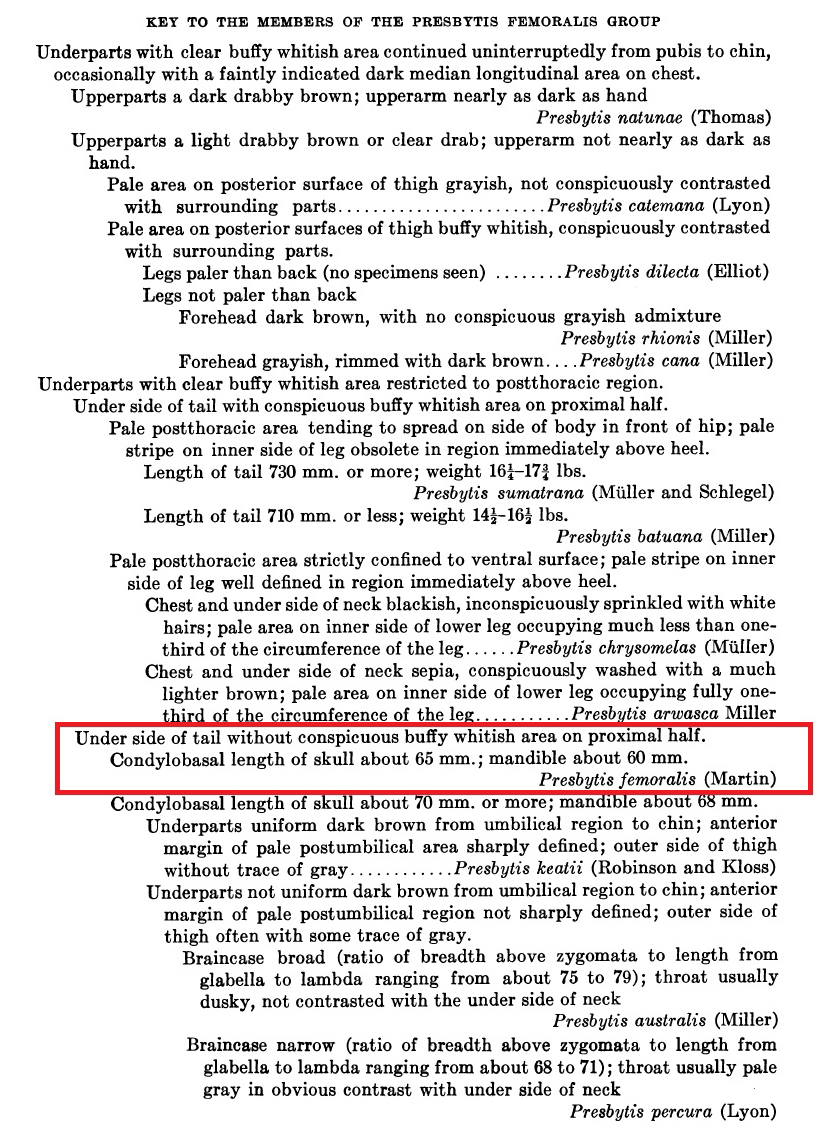

The identification and species description of primates in older literature (before the molecular phylogenetic era of taxonomy) are mostly based on cranial (skull) size and shape, plus, the pelage colouration (coat colour), and sometimes on their vocalization (calls) (for more info on their calls/vocalization, see "Behaviour") [59][62].

The only extant (still in existence) langur/colobus/leaf-monkey (Subfamily: Colobinae; for more info, see "Etymology" and "Phylogeny (Evolutionary History)") in Singapore is the banded leaf monkey (Presbytis femoralis). The only other diurnal (day-time) monkey that you will likely to encounter naturally in Singapore is the long-tailed macaque or the crab-eating macaque (Macaca fascicularis) (Subfamily: Cercopithecinae), which is easily distinguished from the banded leaf monkey by their pelage colouration; in which the banded leaf monkey is primarily blackish in colour whereas the long-tailed macaque is brownish in colour. The long-tailed macaque has pointy ears (the banded leaf monkey has rounded ears), more closely-set eyes, and longer face as compared to the banded leaf monkey. The banded leaf monkey is also 2 to 3 times the size of the common long-tailed macaque that Singaporean are more familiar with (from Andie's TED X NUS 2011 talk; see "Video 10"). (for more info on how the banded leaf monkey of Singapore looked like, see "Descriptions")

The taxonomy and phylogeny of the Presbytis femoralis is complex and frequently revised, in which even the current revision is still subjected to disagreements. (for more information of the phylogeny, see "Phylogeny (Evolutionary History)")

|

| Figure 4: The banded leaf monkey of Singapore hanging on to a tree branch (photo from: Chan Kwok Wai (wildsingapore.per.sg), used with written permission from the author; diagnosis labels added by Siow Jer Jian) |

^ to the top!

2. Ecology

2.1 - Habitat

Where is their home in Singapore?

|

|

| Figure 7: The last banded leaf monkey from BTNR, now kept as part of Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research (RMBR) taxidermal collection. (photo from: Chan Kwok Wai (wildsingapore.per.sg), used with written permission from the author) |

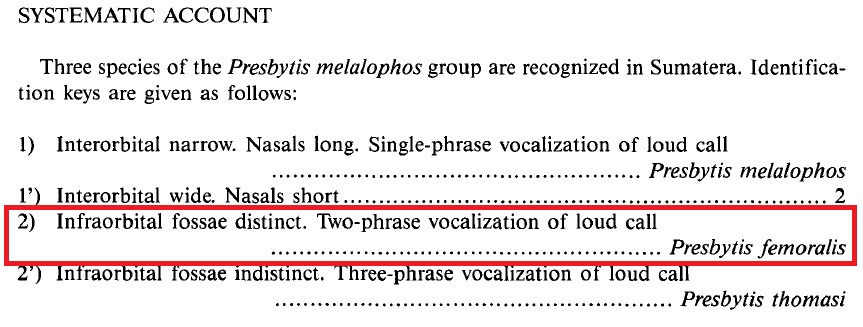

The banded leaf monkey, Presbytis femoralis, are known to be distributed in the Malay Peninsula (with a patch throughout Thailand and Burma, and a separate patch covering both Johor and Singapore) and also Eastern Sumatera (figure 4) [2][3][14][61] (for more info, see “Subspecies”). Pace of extinction can be accelerated by loss of habitat, which in this case, deforestation [32].

While they were once widespread throughout Singapore, they are currently found only in the secondary and swamp forest of the Central Catchment Nature Reserve (CCNR), which only has an area of 4.55km2, particularly around the Upper Seletar Reservoir area [2][3][4][5][50]. This is caused by the clearing of Singapore's original forest cover (95% has been cleared) since the island became a British colony in 1819 [2][9][10][11][29]. At present, Singapore has only 24km2 of the remaining primary forest [9][10][11][29]. Up till the 1920s, the banded leaf monkey of Singapore were once reported in Changi [2][10].

The popular recreational area of Singapore, Bukit Timah Nature Reserve (BTNR) used to house the banded leaf monkey [2][5]. However, due to the construction of an expressway (Bukit Timah Expressway) in 1983 that separated BTNR from CCNR, gene flow stopped and the last banded leaf monkey of BTNR was then found dead in 1987 (figure 7) [2][5][40]. The last banded leaf monkey was an elderly female believed to be mauled by a group of dogs as she descended from the tree, of whether she is committing suicide or not is based on speculations [2][40] (figure 7). In Singapore, the BTNR, and in particularly CCNR are now considered to be Singapore’s major wildlife refuge for many plants and animals of Singapore [5].

In peninsular Malaysia, the primate biomass in the primary forest is dominated by the colobines (Presbytis spp.), whereas secondary forest (forest that has re-grown after major disturbances such as agriculture exploitation), riverine swamp, domestic orchards, paddy fields and so on, commonly host cercopithecines, particularly the long-tailed macaques [39]. This scenario is mirrored to the situation in Singapore [27].

*some of the features in this interactive map have a short description related to the story of the banded leaf monkey as presented on this webpage. Try clicking on them!

(This Google Map showing the location of CCNR was generated by Siow Jer Jian on November, 2013)

2.2 - Population Size

What is the banded leaf monkeys population size in Singapore?

|

Once widespread in Singapore in the earlier part of the last century (20th Century), their population declined drastically due to past deforestation events which resulted from the rapid economic development of Singapore and also poaching activities, though these threats seemed to have somewhat ceased [2][5][9][10]. In the 1980s, its population size was estimated to be around 10 and this figure was increased to approximately 15 in the 1990s [4][41]. The latest estimate by Andie Ang from the National University of Singapore (NUS) in 2010 doubled up the figure to at least 40 individuals [4][5]. This might actually be a sign that the population is somewhat recovering, but it still remained unclear because latest figure may actually be due to greater research efforts [2][5].

With such a small isolated population, they have even been considered to be the ‘living dead’, a term for small group of plants or animals which are still present but likely to be extinct in the near future due to low genetic variability, inbreeding, or absent of mate [7][30][32]. The viability of the banded leaf monkey population hence remains in doubt due to the social constraint on their reproduction and group formation, their fertility, and their genetic constraint (surviving population is genetically related, which also restricted their mate choice) [3][5]. The past bottleneck events (deforestation/loss of habitat) have severely reduced their genetic variability (through genetic comparison of the hypervariable region 1 (HV-1) in their mitochondrial d-loop DNA) which can only be salvaged through reintroductions of related population of Presbytis femoralis from elsewhere (notably Johor, Malaysia) [5][16][17].

^ to the top!

2.3 - Behaviour

|

| Figure 8: The banded leaf monkey caught leaping down to a tree. (photo from: Chan Kwok Wai (wildsingapore.per.sg), used with written permission from the author) |

| How big is a group of banded leaf monkey? * 2-14 individuals has been seen travelling together in at least 6 social groups. How do they travel around?

|

Primates in general, are able to produce referential vocalization, that is to say different types of calls that carry different meanings, much like how we as humans use our voices [2][46][47][48][49]. For the banded leaf monkey of Singapore, their loud calls are actually in a higher range of frequencies as compared to other leaf-monkeys such as the Hanuman langur and the purple-faced langur; which is suggestive of their smaller home range as higher frequency sounds transmit better over short distances [2][39][57].

They are forest specialist (therefore, will not thrive in urban and sub-urban environment) and adapted strictly to an arboreal lifestyle [4][7]. They are known to be active during the daytime (diurnal) and travel in groups of about two to fourteen individuals, of which at least six social groups have been suggested [2][3][11]. They move about by using all four of their limbs (quadrupedal travelling/gait) (see "Video 2") and sometimes seen hopping/leaping from one tree branch to another (see "Video 3"). A behaviour of the adult that serves to indicate the travelling paths to the other group members have been suggested from the observation of the banded leaf monkeys in larger group such as that with the thirteen individuals [2]. Such group will usually involve an adult remaining at the main-crossing point such that all the other group members travel in a one-by-one fashion in front of the adult [2].

They feed primarily in a seated postures (figure 9). They are also observed to exhibit conspecific (among individuals of the same species) grooming behaviour (see "Video 5"). They were suggested to have a social organization within each troop though not entirely confirmed (such that there may be the presence of an alpha male) [2].

Interaction with the long-tailed macaques of Singapore (Macaca fascicularis) has been cordial (warm/friendly) and they do not actively avoid each other [2]. The long-tailed macaques has been occasionally spotted around the proximity of the banded leaf monkey in Singapore [2]. Spatial and temporal utilization of the habitat and food resources in CCNR of each of these species of the Singapore monkeys need further investigation in order to quantify the degree of competition [2].

2.3.1 - Diet

|

| Figure 9: The banded leaf monkey of Singapore adopting a seating posture while feeding. (photo from: Chan Kwok Wai (wildsingapore.per.sg), used with written permission from the author) |

What do they eat?

|

The banded leaf monkey of Singapore feed primarily on fruits (frugivorous), and sometimes on young leaves (folivorous), and less often on flowers (see "Video 7"), a preference uncommon among leaf-eating Asian colobines [2][4][11]. Fruits generally are easily digestible and also contain energy-rich sugars and non-structural carbohydrates though they vary in biochemistry and quality [52][53]. Young leaves, as compared to mature leaves, contained a higher amount of nutritional values, and smaller amount of fibers (in which higher amount of fibers can decrease digestibility of other foods) [54][55][56].

Cellulose is the main constituent of plant cell walls which human and most non-ruminants lack sufficient enzyme to effectively digest it [20][33]. Unlike the Cercopithecinae (eg: the long-tailed macaque; see "Phylogeny (Evolutionary History)" and "Diagnosis"), their long gut/digestive tract and large multi-chambered stomach (which contain a vast array of microflora) help them to digest cellulose, and process plant materials [2][11][44][45][62]. In other words, they possess the fore-stomach fermentation digestive system (a ruminant-like stomach) as with all other colobine monkeys [2].

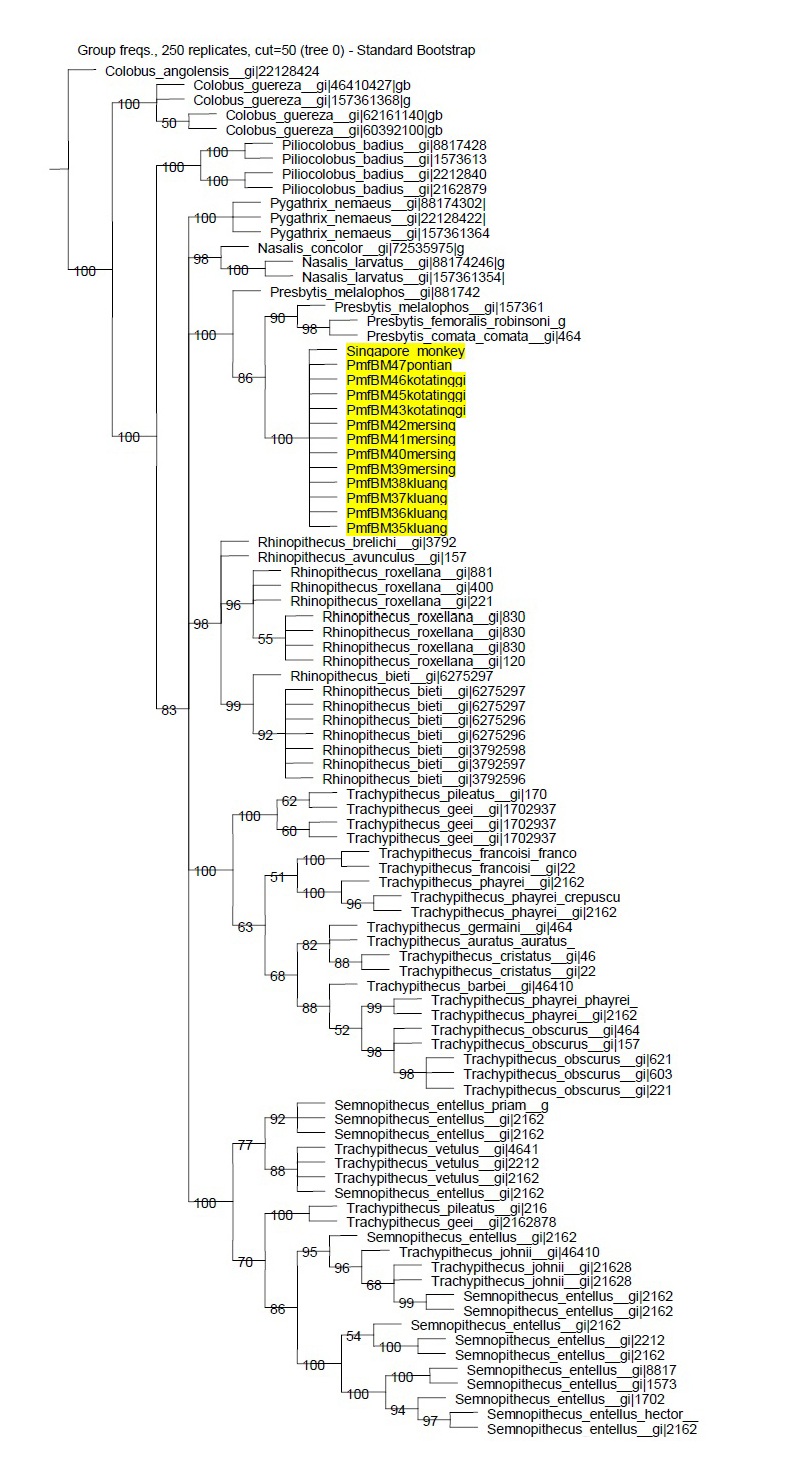

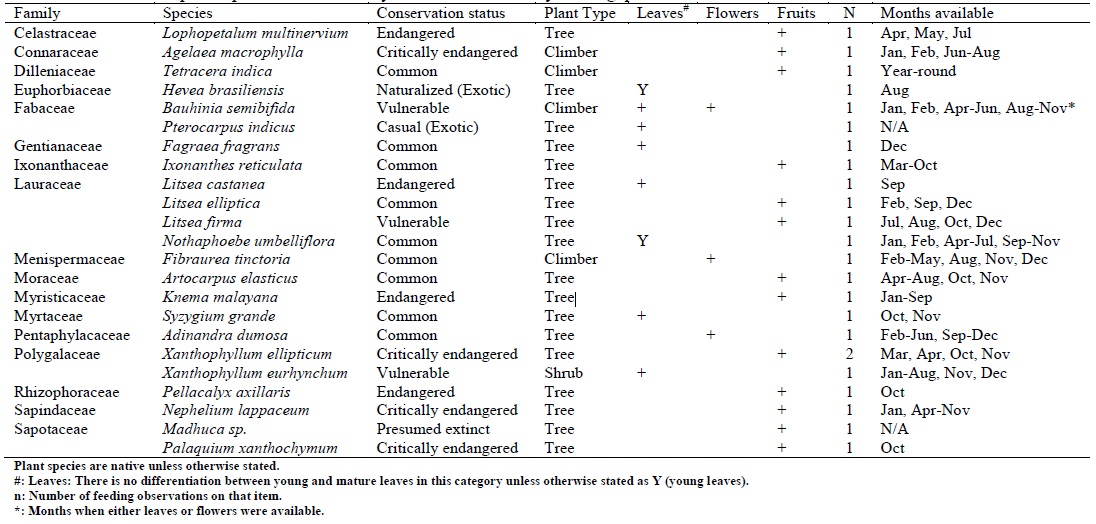

Like other leaf-monkeys, the banded leaf monkey of Singapore is a selective feeder, seldom eating items in proportion to their abundance in the forest [2]. They have been observed to feed on 23 food plant species of which half are locally threatened (figure 10), this shows a predominant preference towards uncommon tree species [2][4]. Andie Ang also claimed that the latest recorded number of plant species consumed by the banded leaf monkey has increased to 27 as more field observations was conducted (personal communication, November 25th, 2013). Prior to Andie's studies, there were no information on the plant species consumed by the banded leaf monkeys in Singapore [2].

|

| Figure 10: Identified plant species consumed by the banded leaf monkey in Singapore (figure adapted from Andie Ang's Master's Thesis; used with written permission from the author) |

^ to the top!

2.4 - Growth & Development

What is their average lifespan?

Do they have a breeding season?

|

Currently, no information is available on the lifespan of this banded leaf monkey (or which the information is obscure). Moreover, it is extremely difficult to obtain data on their reproduction due to their elusive and shy nature [2][3]. A study in CCNR has recorded six births from 2008 to 2010 [3]. This presented evidence that they are still reproducing; and there is at least one birth season in June or July (coinciding with the relatively dry season in Singapore due to the Southwest Monsoon Season from June to September) for three consecutive years [3]. The infants in Singapore was suggested to have low mortality, due to the observation that several survived beyond seven months [3].

|

| Figure 11: A much older infant banded leaf monkey (with black pelage colouration almost similar to adult) feeding on vegetation in Singapore. It is still considered an infant due to some white fur still visible along its hind legs and was being carried during travel. (photo from Andie Ang, used with written permission from the author) |

The infants of Presbytis femoralis have been described as being born mostly with white to pale grey pelage, though orange-coloured ones (unconfirmed sightings) have also been purportedly sighted [3][11]; and with black band running from the head, along the spine through the tail intersected by another black band running from the outer surface of their forearms to both shoulders crossing along their back, creating a characteristic cruciform (cross-like) black pattern on their dorsum (their upperside/back) [3].There is also a faint black band running from the spine to along the hind legs up till the feet [3]. The facial fur and crown are completely white from the frontal view [3]. As they mature, their pelage colouration turn darker and darker, resembling the black adult colouration [3]. It takes approximately six months from birth for the pattern on the head to change into the adults colouration [2][6]. (see "Video 8")

The young of many primate species have distinctively different pelage colouration and pattern from their adults, which was suggested to differentiate the dependant infants from the independent adults [1]. This conspicuous natal pelage colouration is noted to be common within Colobinae as with the banded leaf monkey of Singapore, which was suggested to be an adaptive evolution by the infants for eliciting care and protective response from the older group members [1][3][15][26][62]. This adaptation helps to increase the infants chances of survival [1][3][15][26]. What about camouflaging from potential predators? Well, the infants are usually carried between the hind legs of the carrying adult with their ventral (under) side facing the chest of the carrying adult, hence, their white natal pelage would be matching with the white chest pelage of the adult and most of the infants’ body parts would be concealed by the black pelage on the limbs of the carrying adult (figure 12B) [3]. (see "Video 8")

It was observed that the infants were carried less frequently by the adults even though they might not yet be fully weaned, they were able to jump and move around with the adults in vicinity [3]. When the groups are travelling, the infants are usually carried by the adults [3]. The infants are described to be very active even when the adults were resting or sleeping [3].

This pelage colouration pattern of the infants in CCNR, Singapore is also consistent with that of the infants from the Johor population, further strengthening the evidence that both population belonged to the same subspecies of the banded leaf monkey [3].

| Category |

Distinguishing features |

| Infant - 1 |

From birth until pattern at head changes to adult color. This occurs at about six months of age. *Infant is still white. (0-1 year) |

| Infant - 2 |

From the end of Infant - 1 until the tail is more than three-quarters of the adult length. This occurs at about one year of age. *Infant is fully black. (1-2 year) |

| Juvenile - 1 |

From the end of Infant - 2 until the animal is more than half of the adult body size. This occurs at about two years of age. (2-3 year) |

| Juvenile - 2 |

From the end of Juvenile - 1 until the animal is more than three-quarters of the adult body size. This occurs at about three to four years of age. (3-5 year: 4th & 5th year) |

| Subadult |

From the end of Juvenile - 2 until the animal is of fully adult size. |

| Adult |

Full sized animal (Sexual maturity could not be determined in the field). |

Table 1: Age categories of the banded leaf monkeys (this table was adapted directly from Andie Ang's Master's thesis, 2010 [2], after "Bennett, 1983" [6])

Video 8: Infant banded leaf monkey being carried by the carrying adult. Notice here in the video on the infant's pelage colouration and pattern. (footage from: Andie Ang, used with written permission from the author

^ to the top!

3. Conservation

What is threatening them?

What are Singapore's plans to save this species?

|

Conservation efforts for the banded leaf monkey have largely been hampered by the fact that very little is known about this species. The IUCN status of this species that ranges from Data Deficient, Near Threatened, to Vulnerable is actually rather iffy as the taxonomy status of the species is still under constant debate and reevaluation [2][27][28][42][43]. If they are indeed found to be a unique subspecies and endemic to Singapore, it would then certainly be one of the most endangered primates in the world due to its small population [2][51].

Nevertheless, this species deserves high conservation priority as it represents the national and natural heritage of Singapore [2]. Plus, they are first described from Singapore as well [2] (for more info, see “Type”). Globally, they are listed as vulnerable, but locally in Singapore, they are actually one of the rarest (critically endangered) mammals [4][22][28]. Because of its arboreal lifestyle coupled with the massive clearance of forest in Singapore due to urbanization, the once widespread Presbytis femoralis is now only restricted to the CCNR [4][5]. It was reported by the Singapore National Parks Board (NParks) that the young individuals may be caught and kept as a pet [63].

Previously, they were thought to be on a decline with less than 20 individuals left in the wild, but a study done in 2010 by Andie Ang has shown that the population was larger than once thought (with up to 40 individuals) [11][41]. However, their extremely low genetic variability provided evidence for the lack of genetic recovery though the population may be suggested to be on the rise [5]. This made the population to be extremely vulnerable to environmental disturbances such as diseases [8][35] (For more info on population size estimate and genetic status, see “Population Size”). The threats of habitat loss still exist particularly in areas outside of Singapore in which the oil palm plantations are expanding rapidly [27].

Because of this urgent concern, a NUS master’s project spearheaded by Andie Ang to collect critical information on this species such as its population size, infant development, and feeding ecology has been started in August 2008 [2][4]. In order to study and collect data on this monkey, habituation (familiarization) (see "Video 1") of the monkey with the researcher would be required as they are extremely shy and flee at the sight of humans [2][4].

The establishment that the banded leaf monkeys in Singapore and Johor belonged to the same subspecies through genetic studies of their faeces (figure 17; see "Video 4") and the pelage colouration of both the adults and infants has raised the possibility of translocation between the populations in order to prevent their local extinction in Singapore [3][4][16][17]. A comparative fieldwork of the banded leaf monkeys in Johor would be crucial for generating more information to sustain this monkey in Singapore [4][5]. If translocation of the banded leaf monkeys from Johor to Singapore were to happen, great care must be exercised to ensure that they are indeed from the same species or even arguably the same subspecies, that foreign diseases are not accidentally brought in, and that CCNR can still support more banded leaf monkeys (carrying capacity assessment has to be done) [2][5][30][38]. In spite of that, it seems that the Johor population is also currently being affected by the widespread deforestation at the Southern Peninsular of Malaysia [5].

Captive breeding may sound like an option but without adequate understanding of their biology, rearing them and subsequently encouraging them to breed will not be feasible [30].

As mentioned previously (see the "Habitat" section), the popular recreational area of Singapore, Bukit Timah Nature Reserve (BTNR) used to house the banded leaf monkey which however due to the construction of an expressway in 1983 that separated BTNR from CCNR, gene flow stopped and the last banded leaf monkey of BTNR was then found dead in 1987 (figure 7) [5][40]. The BTNR, and in particularly CCNR are now considered to be Singapore’s major wildlife refuge for many plants and animals of Singapore [5]. The construction (expected to be completed by the end of 2013) of Southeast Asia first eco-link that will reconnect BTNR with CCNR like a flyover across the expressway might help to expand their habitat and food resources [2][5]. However, due to the extirpation of the banded leaf monkey in BTNR, the reconnection will not be useful for the genetic recovery of the population [5].

Throughout the year of 2011, there was a campaign titled, 'Save the Banded Leaf Monkey/ Close to Man, Closer to Extinction' or 'BL-UHM'. The campaign, which was the first primate conservation campaign in Singapore, was conceived by the students of the National University of Singapore (NUS) reading the course/module, 'NM4217: Advanced Communications Campaigns' for the purpose of raising the awareness of and disseminating information about this banded leaf monkey of Singapore and also about the Jane Goodall Institute of Singapore (see "Video 9"). Through this campaign, exhibitions have been set up around Singapore, particularly in NUS with occasional monkey mascot running around the campus. Their official webpage (http://www.savetheblm.org) however has been down, and their only active channel as of today is their official Facebook page at 'www.facebook.com/SaveTheBLM'.

.Video 9: BL-UHM campaign.

Video 10: Andie Ang at TED X NUS (March 26th, 2011) on the banded leaf monkey of Singapore

| “If you look at the monkeys, you can learn many things about the men; if you look at the men, you can learn many things about the madness!” – Mehmet Murat Ildan |

|

| Figure 13: The Banded Leaf Monkey. (Illustrated by: Siow Jer Jian (Nov, 2013)) |

^ to the top!

4. Taxonomy & Systematics

They were first described in 1838 by Martin based on one specimen from Singapore, making Singapore the type locality [2][23] (for more info on Type, see “Type”). The local population of banded leaf monkey in Singapore is currently regarded as a distinct (debatable) subspecies, Presbytis femoralis femoralis [4][11]. They were once thought to be a subspecies of Presbytis melalophos [10][31]. |

4.1 - Taxonavigation

Below are the taxon representatives involved in the Presbytis femoralis species. While the relevance of this archaic Linnaean ranking system is highly contended, it is provided here for the purpose of practicality and ease of reference to specific clades (and taxon names) in the current phylogenetic system.

The general consensus is that rankings are misleading and irrelevant in modern day taxonomy due to their arbitrariness and differences within different groups of organisms (thereby not effective to make any comparison between and within each ranks). Plus, this ranking system also does not demonstrate the evolutionary history of any organisms that it purportedly does.

| Kingdom: |

Animalia |

||||||||

| Phylum: |

Chordata |

||||||||

| Class: |

Mammalia |

||||||||

| Order: |

Primates |

||||||||

| Family: |

Cercopithecidae |

||||||||

| Subfamily: |

Colobinae |

||||||||

| Genus: |

Presbytis |

||||||||

| Species: |

Presbytis femoralis (Martin, 1838) |

||||||||

| Subspecies: |

Presbytis femoralis femoralis |

4.2 - Nomenclature

Accepted Scientific name: Presbytis femoralis (Martin, 1838)

4.2.1 - Etymology

They are part of the Asian colobines and may sometimes be described as a colobus (a slender leaf-eating monkey with silky fur, from Greek: kolobos ‘curtailed’ (with reference to its shortened thumbs compared to its other fingers) [34]. They may also be referred to as a langur (a long-tailed slender Asian leaf-monkey with a characteristic loud call [Presbytis and other genera]), in which the word langur means ‘tail’ via Hindi from the Sanskrit word langula [14][34]. The term ‘banded’ in their common name is most probably given because of the white bands traversing the inner part of their limbs.

The epithet (adjective or phrase expressing a quality of the thing mentioned) in their scientific name, femoralis, refers to the pale colouration on their ventral (underside) area which continues on as a broad, sharply defined stripe on the inner surface of their thigh [23]. According to the Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary (http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary), the term Presbytis is akin to Greek pro (before) and bainein (to go) or presbyteros (old man, elder).

4.2.2 - Common Names (Vernacular Names)

- Banded langur [11][27][63]- Banded leaf monkey [27][63]- Banded surili [14][27]- Raffles’ banded langur [28]- Raffles’ surili [11]- Mützenlanguren (German for 'capped langurs') [58]

4.2.3 - Synonyms

- Simia maura Linnaeus, 1822 [23]- Semnopithecus femoralis Martin, 1838 [23]- Semnopithecus neglectus Schlegel, 1876 [23]- Presbytis maura (Linnaeus, 1822) [23]- Presbytis neglectus (Schlegel, 1876) [27]- Presbytis australis Miller, 1913 [27]- Presbytis femoralis Miller, 1913 [23]- Presbytis keatii Robinson & Kloss, 1991 [27]

They were once thought to be a subspecies of Presbytis melalophos [10][31]. “It was separated from P. melalophos by Wilson and Wilson (1977), and recognized as a species by Aimi et al. (1986)” (retrieved from [27]).

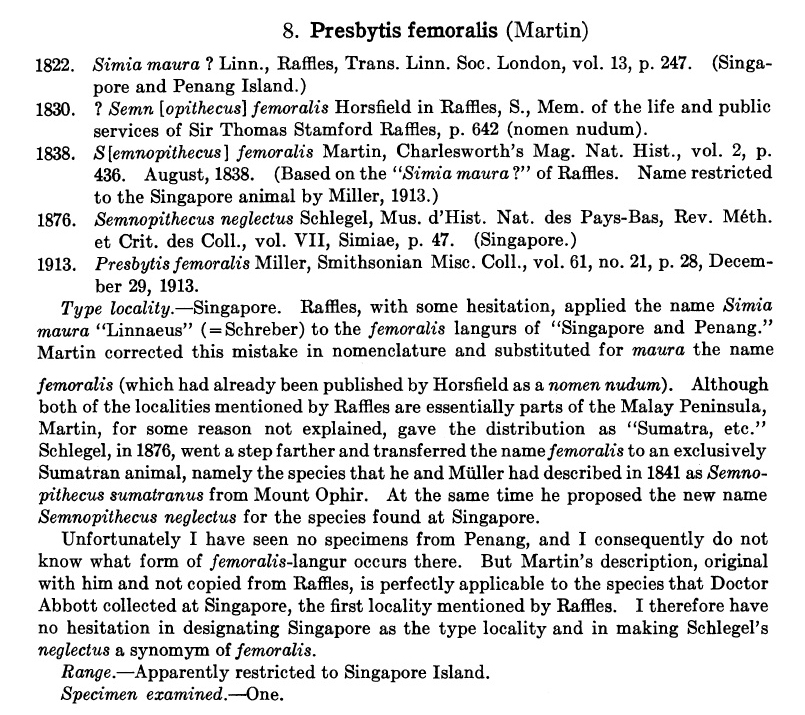

|

| Figure 14: Description of name changes and designation of type locality (adapted from Miller (1934) [23]) |

(for more on Type and Type locality, see "Type")

^ to the top!

4.3 - Subspecies

This species page can be said to be written mainly on the Presbytis femoralis of Singapore, also known as the Presbytis femoralis femoralis. However, at least three subspecies of Presbytis femoralis are currently recognized, though its taxonomy is still being actively debated [2][3][4][5][61] (for more info on the debate, see “Phylogeny (Evolutionary History)”).

1) Occurring around the East-central Sumatra: Presbytis femoralis percura

2) Occurring around the Northern Malay Peninsula: Presbytis femoralis robinsoni

3) Occurring around Singapore and Johor: Presbytis femoralis femoralis

4.4 - Phylogeny (Evolutionary History)

|

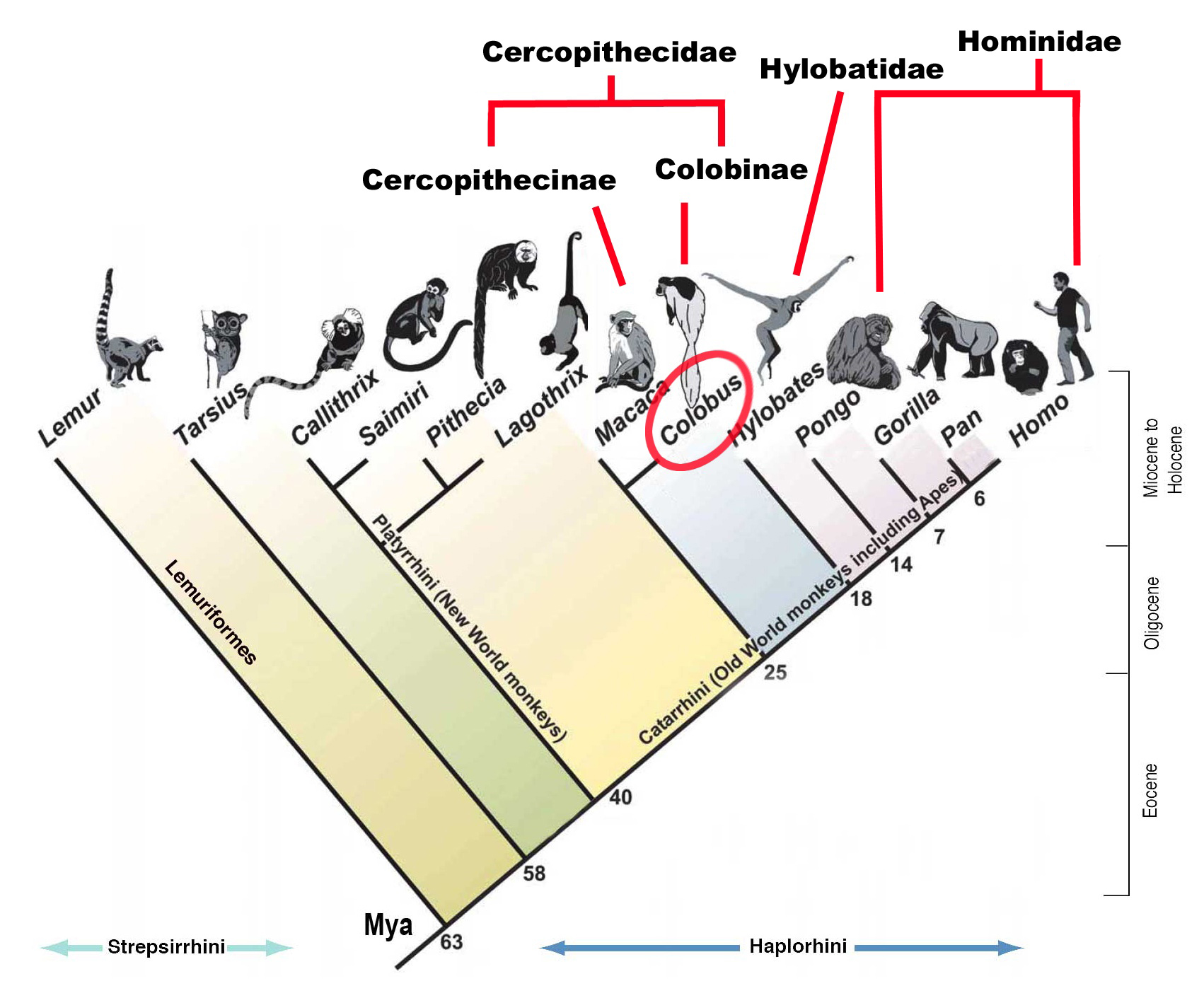

| Figure 16: Phylogeny tree showing the different clades of the genera in the order Primates. The banded leaf monkey belonged to the Colobinae subfamily together with the genus Colobus (a genus of the African colobines). (figure from Wikimedia Commons, used under the public domain free license; family and subfamily labels inserted by Siow Jer Jian) |

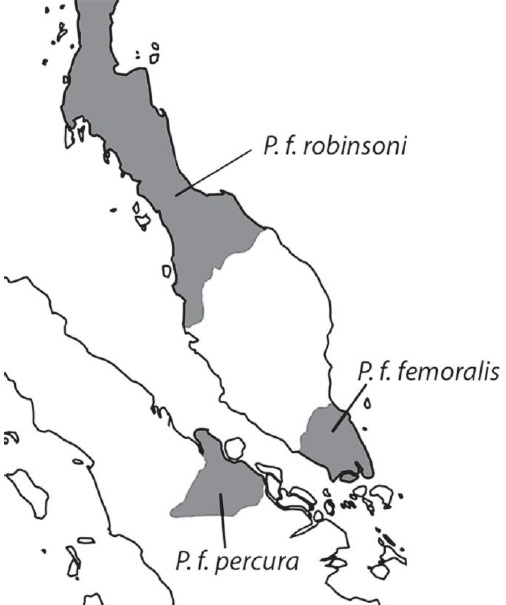

They are mammals belonging to the order Primates (which includes lemurs, lorises, tarsiers, apes, and humans) [65], family Cercopithecidae (family denoting the Old World monkeys; in Singapore, only four species of this family are recorded, i.e., the banded leaf monkey, long-tailed macaque, pig-tailed macaque (locally extinct), and silvered leaf monkey (extinct)), and subfamily Colobinae (the Asian colobines) [2][11][12][21][64]. The Asian colobines have been tentatively divided into two subgroups, the odd-nosed group (including the genera: Nasalis, Pygathrix, Rhinopithecus, and Simias) and the langur/leaf-monkey group (including the genera: Presbytis, Semnopithecus, and Trachypithecus) [2][13][19][62].

For the odd-nosed group, monophyly (descended from a common evolutionary ancestor or ancestral group, and not shared with any other group) has been resolved though the sister group remained contentious [36][62]. Every individual for the langur group used to be grouped into the genus Presbytis with just five species (P. aygula, P. melalophos, P. frontata, P. rubicunda and P. potenziani) [24][60]. Today, the individuals in the langur group was split into three genera, i.e., the Semnopithecus (from South Asia and adjacent areas), the Trachypithecus (from much of Southeast Asia and parts of South Asia and China), and the Presbytis (restricted to Southeast Asia), with 32 species, though the monophyly of the langur group is still being challenged [2][37][62]. The genus Presbytis, also known as the surilis, consist of 11 species and numerous subspecies from all over Southeast Asia [62].

Resolving the phylogeny of langurs have been plagued with the lack of molecular data due in large to the difficulty in obtaining these data caused from their elusive nature [18]. This lack of molecular information is especially pronounced in the genus Presbytis despite the fact that they are the most diverse genera in Columbinae with complex distribution pattern, resulting in a lot of dispute in their phylogenetic relationship and their number of species and subspecies [2]. Prior to the study by Andie Ang, there was no genetic data on the population of Presbytis femoralis of Singapore [2][5].

The phylogenetic relationship and the taxonomy of the currently recognized three subspecies, i.e. P. f. femoralis, P. f. robinsoni, and P. f. percura is still currently unresolved (for more info, see “Subspecies”). The taxonomy of the Johor population and Singapore population used to be disputed due to alleged difference in the adult (Johor population was purported observed to have more white fur on the underparts [10]) and infant pelage colouration [2]. This dispute was tentatively resolved in 1994 by Hüttche through studies on the pelage colouration, vocalization and cranial measurements of the banded leaf monkey between the Johor and Singapore population [2][16]. Hüttche noted that both population have no obvious differences in terms of the vocalization and cranial measurement, however, the ventral pelage colouration of individuals in the Singapore population tend to be darker [16]. Nevertheless, Hüttche concluded that the ventral pelage colouration may actually be representing the variability at the individual-level and not sufficient to warrant a classification into separate subspecies [16].

A recent study by Andie Ang [2] comparing the faecal DNA sample (see "Video 4") from Singapore’s banded leaf monkey with the DNA samples of the Johor’s banded leaf monkey then provided further evidence that the Singapore and Johor population belonged to the same subspecies, i.e., P. f. femoralis. Despite that, their taxonomy is still highly disputed. Andie's comparison study of the mitochondrial DNA also suggested that the P. f. robinsoni from the Northern Malay peninsula might actually belong to another species altogether instead of being a subspecies of P. femoralis [2].

“It was separated from P. melalophos by Wilson and Wilson (1977), and recognized as a species by Aimi et al. (1986)” (retrieved from [27]).

4.4.1 - Type

A type is a specimen (or in some cases, specimens) which serve to act as a physical representation (exemplar) in which the description of a scientifically named species is based upon.

They were first described in 1838 by Martin based on a specimen (collected by Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles) from Singapore (figure 14), making Singapore their type locality [2][5][23]. Hence, the nominate subspecies (subspecies having the same epithet as the species to which it belongs), Presbytis femoralis femoralis denotes the subspecies from the Singapore population.

The syntype (one of a group of specimens which is an exemplar for the described species, where no holotype (a single specimen clearly designated in the original description) was designated) tagged as Presbytis melalophos femoralis (the banded leaf monkey was once thought to be the subspecies of P. melalophos) is available at the zoology collection of the Natural History Museum of London with the reference number of 1879.11.21.594 [25].

4.4.2 - Genetic Barcode

Currently, there are no publicly available "DNA Barcode" which is relevant for the banded leaf monkey (Presbytis femoralis).

GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and BOLDSYSTEMS (http://www.boldsystems.org/) are used to search for genetic barcodes that are available online. Only GenBank yielded a result for Presbytis femoralis, in which the protein gene, immunoglobulin alpha heavy chain, is available that comes with the publication by Sumiyama,K., Saitou,N. and Ueda,S. (2009). This protein gene is not as useful as a barcode for Presbytis femoralis as protein genes are highly conserved and hence, even BLAST-ing the gene in GenBank revealed 100% similarity with other Presbytis spp. and also closely related genera like Colobus (African Colobine) and even Macaca (from another subfamily, Cerchopithecinae, instead of Colobinae that Presbytis femoralis is part of).

^ to the top!

References

[1] Alley T.R. (1980). Infantile colouration as an elicitor of caretaking behavior in Old World Primates. Primates. 21(3): 416–429.

[2] Ang A.H.F. (2010a). Banded leaf monkeys in Singapore: Preliminary data on taxonomy, feeding ecology, reproduction, and population size. Master’s thesis, National University of Singapore.

[3] Ang A.H.F, Ismail M.R.B., & Meier R. (2010). Reproduction and Infant Pelage Colouration of the Banded Leaf Monkey (Mammalia: Primates: Cercopithecidae) in Singapore. The Raffles Bulletin of Zoology. 58(2): 411-415. Retrieved from [15th October 2013]: http://rmbr.nus.edu.sg/rbz/biblio/58/58rbz411-415.pdf

[4] Ang A.H.F. (2011). Back From The Brink. In Singapore Biodiversity, An Encyclopedia of the Natural Environment and Sustainable Development. (p. 23). Singapore: Editions Didier Millet.

[5] Ang A.H.F, Srivasthan A., Md.-Zain B.M., Ismail M.R.B., & Meier R. (2012). Low genetic variability in the recovering urban banded leaf monkey population of Singapore. The Raffles Bulletin of Zoology. 60(2): 589-594. Retrieved from [16th October 2013]: http://rmbr.nus.edu.sg/rbz/biblio/60/60rbz589-594.pdf

[6] Bennett E.L. (1983). The banded langur: ecology of a colobines in West Malaysian rainforest. PhD dissertation, University of Cambridge. p. 290.

[7] Brook B.W., Sodhi N.S. & Ng P.K.L. (2003). Catastrophic extinctions follow deforestation in Singapore. Nature. 424: 420–423.

[8] Charpentier M.J.E., Williams C.V. & Drea C.M. (2008). Inbreeding depression in ring-tailed lemurs (Lemur catta): genetic diversity predicts parasitism, immunocompetence, and survivorship. Conservation Genetics. 9: 1605–1615.

[9] Chasen F.N. (1924). A preliminary account of the mammals of Singapore Island. Singapore Naturalist. 4: 76–86.

[10] Chasen F.N. (1940). A handlist of Malayan mammals. Bulletin of the Raffles Museum. 15: 1–209.

[11] Chua M.A.H. & Lim K.K.P. (2011a). Banded Leaf Monkey. In Singapore Biodiversity, An Encyclopedia of the Natural Environment and Sustainable Development. (p. 235). Singapore: Editions Didier Millet.

[12] Chua M.A.H. & Lim K.K.P. (2011b). Monkeys. In Singapore Biodiversity, An Encyclopedia of the Natural Environment and Sustainable Development. (p. 382). Singapore: Editions Didier Millet.

[13] Groves C.P. (1970). The forgotten leaf-eaters and the phylogeny of Colobinae. In: Napier J.R.& Napier P.H. (eds.), Old World monkeys: Evolution, Systematics, and Behavior. (pp. 555-586). New York: Academic Press.

[14] Groves C.P. (2001). Primate Taxonomy. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press.

[15] Hrdy, S.B. (1976). The care and exploitation of non-human primate infants by conspecifics other than the mother. In: Rosenblatt J.S., Hinde R.A., Shaw E., & Beer C. (eds.), Advances in the Study of Behavior. (Vol. 6, pp. 101-158). New York: Academic Press.

[16] Hüttche C. (1994). The ecology, taxonomy and conservation status of the Banded Leaf Monkey (Presbytis femoralis femoralis) in Singapore. Diploma thesis. Free University Berlin.

[17] IUCN (1987). IUCN Position Statement on Translocation of Living Organisms: Introductions, Re-introductions and Re-stocking. Retrieved from [12th November 2013]: http://intranet.iucn.org/webfiles/doc/SSC/SSCwebsite/Policy_statements/IUCN_Position_Statement_on_Translocation_of_Living_Organisms.pdf

[18] Jablonski, N.G. & Peng Y.Z. (1993). The phylogenetic relationships and classification of the snub-nosed langurs of China and Vietnam. Folia Primatologica. 60:36-55.

[19] Jablonski N.G. (1998). The evolution of the doucs and snub-nosed monkeys and the question of the phyletic unity of the odd-nosed colobines. In: Jablonski N.G. (ed.), Natural History of the Doucs and Snub-nosed Monkeys. (pp. 13-52). New Jersey: World Scientific Publishing Company.

[20] Joshi S. & Agte V. (1995). Digestibility of dietary fiber components in vegetarian men. Plant Foods for Human Nutrition. 48(1): 39-44. doi: 10.1007/BF01089198. PMID 8719737.

[21] Kirkpatrick R.C. (2007). The Asian Colobines. In: Campbell C.J., Fuentes A., MacKinnon K.C., Panger M., Bearder S. (eds.), Primates in Perspective. (pp. 186-200). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[22] Lim K.K.P., Subaraj R., Yeo S.H., Lim N., Lane D., & Lee B.Y.H. (2008). Mammals. In: Davison G.W.H., Ng P.K.L., & Ho H.C. (eds.), The Singapore Red Data Book: Threatened Plants & Animals of Singapore, second edition. (p. 198). Singapore: The Nature Society.

[23] Miller G.S.Jr. (1934). The langurs of the Presbytis femoralis group. Journal of Mammalogy. 15: 124-137. Retrieved from [12th September 2013]: http://www.jstor.org/discover/10.2307/1373983?uid=3738992&uid=2&uid=4&sid=21102908978857

[24] Napier J.R. & Napier P.H. (1967). A Handbook of Living Primates. London: Academic Press.

[25] Natural History Museum of London (2005). Zoology collection database. The Natural History Museum, London official webpage. Retrieved from [10th November 2013]: http://www.nhm.ac.uk/research-curation/scientific-resources/collections/zoological-collections/zoology-specimen-database//?action=display&irn=3486270&EntIdeScientificNameLocal_tab=presbytis+femoralis&RecordsPerPage=10&page=2&startAt=1&tab=determination#tabs

[26] Newton P.N. & Dunbar R.I.M. (1994). Colobine monkey society. In: Davies, A.G. & J. F. Oates (eds.), Colobine Monkeys: Their Ecology, Behavior and Evolution. (pp. 311-346). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

[27] Nijman V., Geissman T., & Meijaard E. (2008a). Presbytis femoralis. In IUCN 2013. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.1. Retrieved from [10th November 2013]: http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/18126/0

[28] Nijman V., Geissman T., & Meijaard E. (2008b). Presbytis femoralis ssp. femoralis. In IUCN 2013. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.1. Retrieved from [10th November 2013]: http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/39801/0

[29] Ng P.K.L. & Corlett R.T. (2011). Biodiversity In Singapore: An Overview. In Singapore Biodiversity, An Encyclopedia of the Natural Environment and Sustainable Development. (pp. 18-27). Singapore: Editions Didier Millet.

[30] Ng P.K.L., Tan H.T.W. & Lim K.K.P. (2011). The Living Dead. In Singapore Biodiversity, An Encyclopedia of the Natural Environment and Sustainable Development. (pp. 103). Singapore: Editions Didier Millet.

[31] Oates J.F., Davies A.G. & Delson E. (1994). The diversity of living colobines. In: Davies A.G. & Oates J.F. (eds.), Colobine Monkeys: Their Ecology, Behavior and Evolution. (pp. 45-73). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

[32] Pitra C., Hüttche C. & Niemitz C. (1995). Population viability assessment of the banded leaf monkey in Singapore. Primate Report. 42: 47–59.

[33] Slavin J.L., Brauer P.M., & Marlett J.A. (1981). Neutral detergent fiber, hemicelluloses and cellulose digestibility in human subjects. The Journal of Nutrition. 111(2): 287-297. PMID 6257867.

[34] Soanes C. & Stevenson A. (eds.) (2009). Concise Oxford English Dictionary, 11th Edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[35] Spielman D., Brook B.W., Briscoe D.A. & Frankham R. (2004). Does inbreeding and loss of genetic diversity decrease disease resistance? Conservation Genetics. 5: 439–448.

[36] Sterner K.N., Raaum R.L., Zhang Y.P. Stewart C.-B., & Disotell T.R. (2006). Mitochondrial data support an odd-nosed colobines clade. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 40: 1-7.

[37] Ting N., Tosi A.J., Li Y., Zhang Y.P., Disotell T.R. (2008). Phylogenetic incongruence between nuclear and mitochondrial markers in the Asian colobines and the evolution of the langurs and leaf monkeys. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 46: 466-474.

[38] Viggers K.L., Lindenmayer D.B. & Spratt D.M. (1993). The importance of disease in reintroduction programmes. Wildlife Research. 20: 687–698.

[39] Wikibooks (2013). Applied Ecology/ Case Studies/ Asian Rainforest Politics. In: en.wikibooks.org. Retrieved from [12th November 2013]: http://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Applied_Ecology/Case_Studies/Asian_Rainforest_Politics

[40] Yang C.M. & Lua H.K. (1988). A report of a banded leaf monkey found dying near the Bukit Timah Nature Reserve. Pangolin. 1: 23.

[41] Yang C. M., Yong K., & Lim K.K.P. (1990). Wild mammals of Singapore. In: Chou L.M. & Ng P.K.L. (eds.), Essays in Zoology. (pp. 1-23). Department of Zoology, National University of Singapore.

[42] Nijman V., Geissman T., & Meijaard E. (2008b). Presbytis femoralis ssp. percura. In IUCN 2013. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.1. Retrieved from [17th November 2013]: http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/39805/0

[43] Nijman V., Geissman T., & Meijaard E. (2008b). Presbytis femoralis ssp. robinsoni. In IUCN 2013. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.1. Retrieved from [17th November 2013]: http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/39806/0

[44] Bauchop T. & Martucci, R.W. (1968). Ruminant-like digestion of the langur monkey. Science. 161: 698-700.

[45] Strasser E. & Delson E. (1987). Cladistic analysis of cercopithecid relationships. Journal of Human Evolution. 16: 81-99.

[46] Marler P., Evans C.S., & Hauser M.D. (1992). Animal signals: motivational, referential, or both? In: Papousek H., Jurgens U. & Papousek M. (eds.), Nonverbal Vocal Communication: Comparative and Developmental Approaches (pp. 66-86). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

[47] Seyfarth R.M., Cheney D.L., & Marler P. (1980). Vervet monkey alarm calls: semantic communication in a free-ranging primate. Animal Behaviour. 28:1070-1094.

[48] Zuberbühler K. (2001). Predator-specific alarm calls in Campbell’s guenons. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 50: 414-422.

[49] Zuberbühler K., Noë R., & Seyfarth R.M. (1997). Diana monkey long-distance calls: messages for conspecifics and predators. Animal Behaviour. 53: 589-604.

[50] National Parks Board (2007). Facts and Figures. Retrieved from [18th November 2013]: http://www.nparks.gov.sg/cms/docs/about-us/Facts%20Figures.pdf

[51] Ang A.H.F. (2010b). Banded Leaf Monkey Research @ NUS. Retrieved from [18th November 2013]: http://evolution.science.nus.edu.sg/monkey.html

[52] Kay R.N.B. & Davies A.G. (1994). Digestive physiology. In: Davies, A. G., and Oates, J. F. (eds.), Colobine Monkeys: Their Ecology, Behaviour, and Evolution. (pp. 229–249). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

[53] Waterman P.G. & Kool K.M. (1994). Colobine food selection and plant chemistry. In: A. G. Davies & J. F. Oates (eds.), Colobine monkeys: Their ecology, behaviour and evolution. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

[54] Janis C. (1976). Evolutionary strategy of Equidae and origins of rumen and cecal digestion. Evolution. 30: 757-774.

[55] Oates J.F., Waterman P.G., & Choo G.M. (1980). Food Selection by the South Indian Leaf-Monkey, Presbytis johnii, in Relation to Leaf Chemistry. Oecologia. 45: 45-56.

[56] McKey D.B., Gartlan J.S.,Waterman P.G., & Choo G.M. (1981). Food selection by black colobus monkeys (Colobus satanas) in relation to food chemistry. Biological Journal of the Linnaean Society. 16: 115-146.

[57] Mitani J.C. & Stuht J. (1998). The Evolution of Nonhuman Primate Loud Calls: Acoustic Adaptation for Long-distance Transmission. Primates. 39: 171-182.

[58] Wikipedia (2013). Surili. In Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Retrieved from [19th November 2013]: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Surili

[59] Aimi M. & Bakar A. (1992). Taxonomy and Distribution of Presbytis melalophus Group in Sumatera, Indonesia. Primates. 33(2): 191-206

[60] Tilson R.L. (1976). Infant coloration and taxonomic affinity of the Mentawai Islands leaf monkeys, Presbytis potenziani. Journal of Mammalogy. 57: 766-769.

[61] Encyclopedia of Life (2013). Banded Leaf Monkey (Presbytis femoralis). Encyclopedia of Life. Retrieved from [23rd November 2013]: http://eol.org/pages/310648/overview

[62] Fleagle J.G. (1999). Old World Monkeys. (pp. 119-150). Primate adaptation and evolution. San Diego: Academic Press.

[63] National Parks Board (2013). Presbytis femoralis (Martin, 1838). NParks Flora & Fauna Web. Retrieved from [23rd November 2013]: https://florafaunaweb.nparks.gov.sg/Special-Pages/animal-detail.aspx?id=224

[64] Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research (2013a). Cercopithecidae. The DNA of Singapore. Retrieved from [23rd November 2013]: http://rmbr.nus.edu.sg/dna/organisms/listing/20/1/481/1

[65] Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research (2013b). Primates. The DNA of Singapore. Retrieved from [23rd November 2013]: http://rmbr.nus.edu.sg/dna/organisms/listing/20/1/464/1

^ to the top!

Documentation (Making of this Webpage)

Here are the files (in .PDF, .DOCX, and .DOC format) that document the search efforts and literature search (somewhat) chronologically (a.k.a. the making of this webpage) plus issues pertaining to copyrights (how the permissions were obtained and so on):-

Siow Jer Jian - Documentations (Banded Leaf Monkey).pdf

Siow Jer Jian - Documentations (Banded Leaf Monkey).docx

Siow Jer Jian - Documentations (Banded Leaf Monkey).doc

^ to the top!

Revisions

^ to the top!

Show me you're alive!!

You can help to contribute to the depository of information on the banded leaf monkey (Presbytis femoralis) in this "species page" by clicking on the Discussion tab at the top of this page. The top 10 most recent comments/posts will be listed below here.

| Subject | Author | Replies | Views | Last Message |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Comment! | 0 | 71 |

Nov 27, 2013 by |

^ to the top!

<est. November 14th, 2013>

^ to the top!