Python reticulatus (Schneider, 1801)

|

| Two reticulated pythons (Credit: Jinterwas) |

|

| Typical colourful reticulation of scales of a reticulated python (Credit: Lee Bee Yan) |

Vernacular (Common name): Reticulated python

Binomial (Scientific name): Python reticulatus or Broghammerus reticulatus (Schneider, 1801)

Synonyms: Boa reticulata (Schneider, 1801), Boa rhombeata (Schneider, 1801), Boa phrygia (Shaw, 1802), Broghammerus reticulatus dalegibbonsi (Hoser, 2004), Broghammerus reticulatus euanedwardsi (Hoser, 2004), Broghammerus reticulatus haydnmacphiei (Hoser, 2004), Broghammerus reticulatus neilsonnemani (Hoser, 2004), Broghammerus reticulatus patrickcouperi (Hoser, 2004), Broghammerus reticulatus stuartbigmorei (Hoser, 2004), Coluber javanicus (Shaw, 1802), Morelia reticulatus (Welch, 1988), Python schneideri (Merrem, 1820)

Python reticulatus was first described by Schneider in 1801 in the publication titled 'Historia amphibiorum naturalis et literaria II' (History of Natural and Amphibians Literary II). In his descriptions, Schneider referred to a holotype specimen and illustrations by Albertus Seba in his book 'Locupletissimi rerum naturalium thesauri' (The Wealthiest are the Treasurers of Natural Things) which was published between 1734-1765. Synonym names occur when scientists discuss and label animal specimens under different names when in actual fact they are referring to the same original species, in this case, the reticulated python as described by Schneider

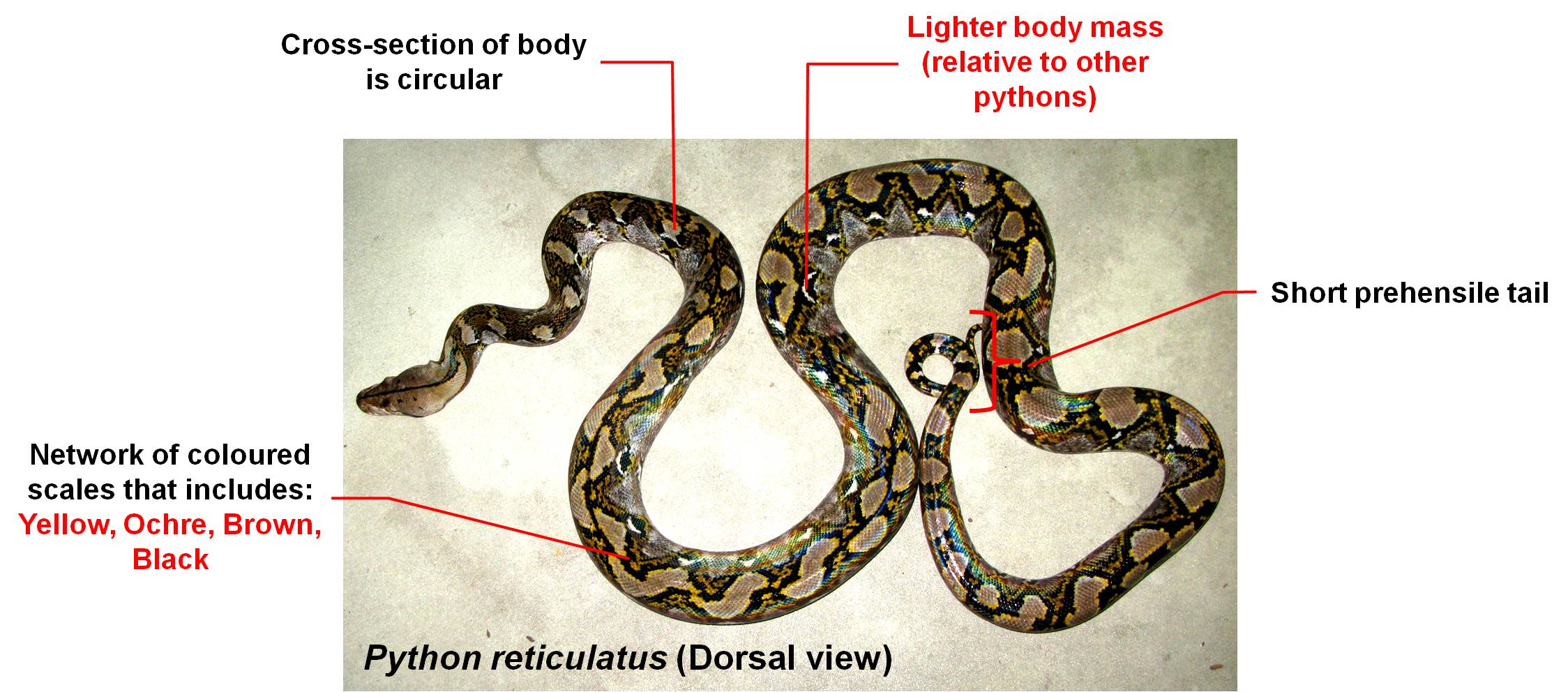

Unfortunately, Schneider did not explain why he named the species 'reticulatus'. But scientists have suggested that the name came about due to the stunning network, or reticulation, of coloured scales adorning the python's body [1] . Jump to Type Information to find out more about holotypes and other type specimens.

(Return to Table of Contents)

- Broghammerus reticulatus dalegibbonsi (Hoser, 2004)

- Broghammerus reticulatus euanedwardsi (Hoser, 2004)

- Broghammerus reticulatus haydnmacphiei (Hoser, 2004)

- Broghammerus reticulatus neilsonnemani (Hoser, 2004)

- Broghammerus reticulatus patrickcouperi (Hoser, 2004)

- Broghammerus reticulatus stuartbigmorei (Hoser, 2004)

However, these subspecies has not been officially recognized by the Integrated Taxonomic System (ITIS) which catalogues new species and taxonomic name changes. Further information on this page will refer to the nominate (original) race P. reticulatus.

Jump to Evolutionary Context to find out more about the genus reclassifications.

(Return to Table of Contents)

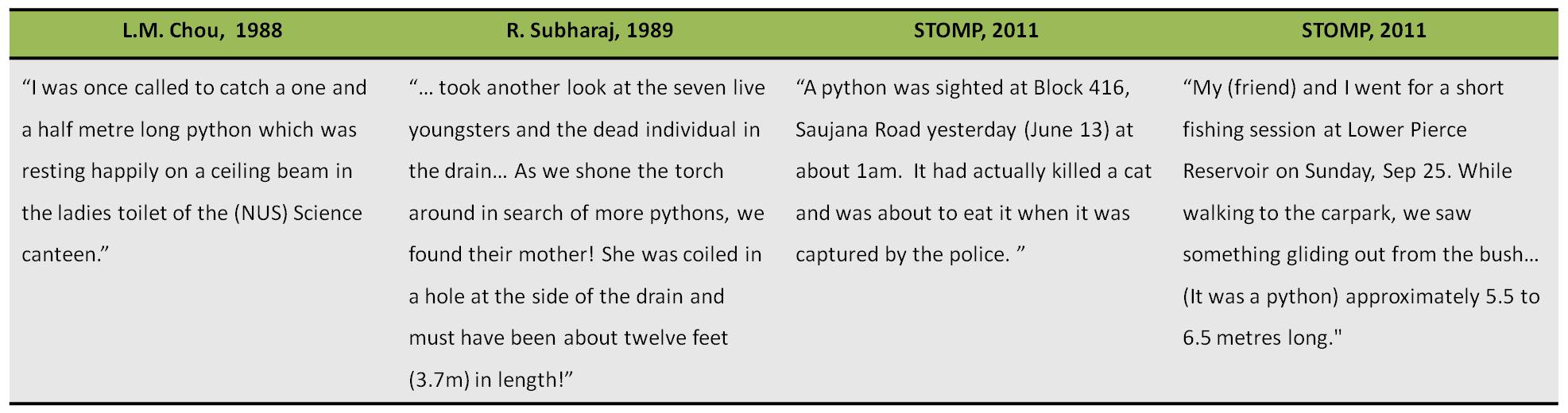

|

|||||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

|||||

(Return to Table of Contents)

|

|

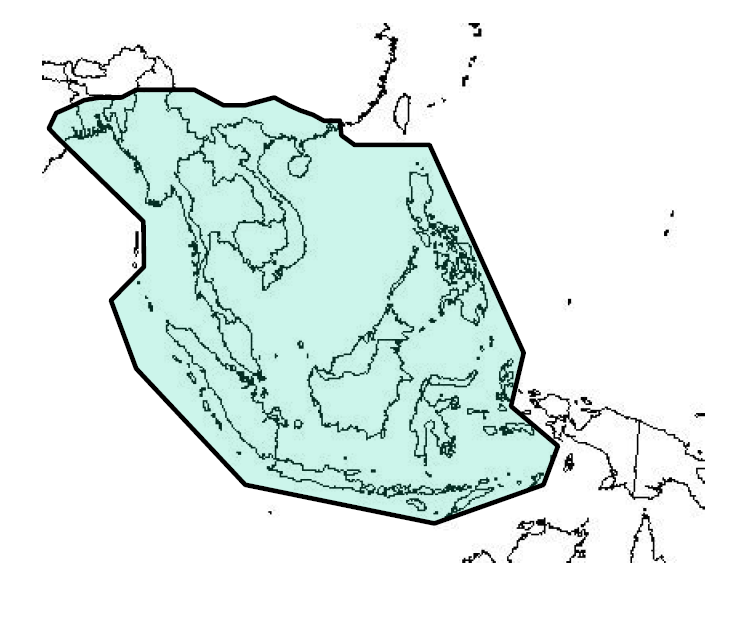

| Known natural geographic range of the Reticulated Python (Credit: Reed & Rodda, 2009) |

Distribution and density of reticulated python specimens around the world based on GBIF Data Portal records . |

The native range of Python reticulatus stretches across Asia. The python has been found as far south as the islands of Indonesia and in some parts of India and China. The species is restricted, thus far, to wet tropical climates, although it may be able to tolerate short dry seasons [6] .

Countries with confirmed native populations include:

- Bangladesh

- Brunei

- Cambodia

- China (southern regions but native presence often disputed)

- India

- Indonesia

- Laos

- Malaysia

- Burma (Myanmar)

- Philippines

- Singapore

- Thailand

- Vietnam

(Return to Table of Contents)

|

||

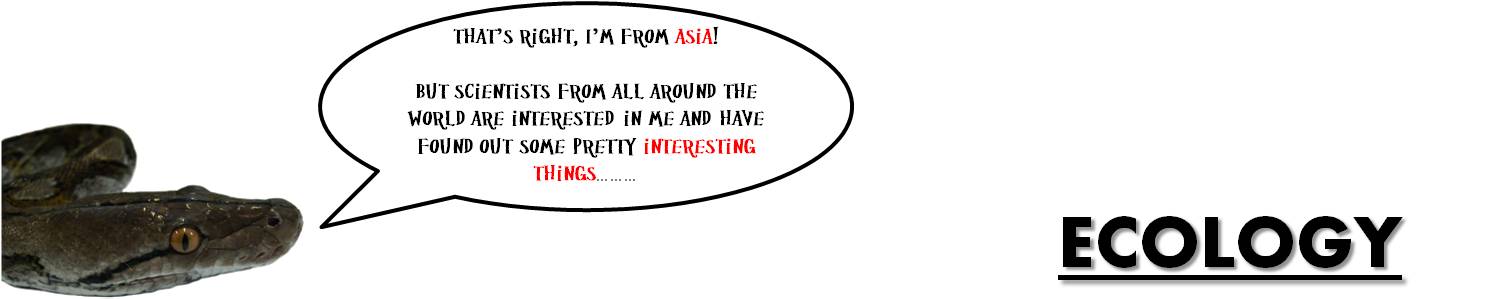

| Descriptions of python habitat preference |

Feeding behaviour of a captive reticulated python at Little Rock Zoo. |

Behaviour of a wild reticulated python when provoked. |

HABITAT

The habitat preference of Python reticulatus is not well known since the species is particularly difficult to study in the wild. But several studies suggest that the python is capable of establishing itself in a wide range of habitats including riparian zones, tropical rainforests (primary and secondary), tropical dry forests, plantations and even urban areas [7] [8] .The uncertainty is largely due to conflicting accounts of the P. reticulatus choice of habitats Some observations have noted that the python has incredible tolerance for highly urbanised and populated areas while some claim that these snakes only inhabit the deepest parts of the forests. The amusing descriptions shown above illustrate perfectly, the differing opinions that exist within the literature.POPULATION

The population density and health of wild P. reticulatus populations are largely unknown. This is despite the fact that there is substantial commercial trade in the species. In fact, biological and conservation studies often rely on specimens collected for the trade [9] .PREY AND FEEDING BEHAVIOUR

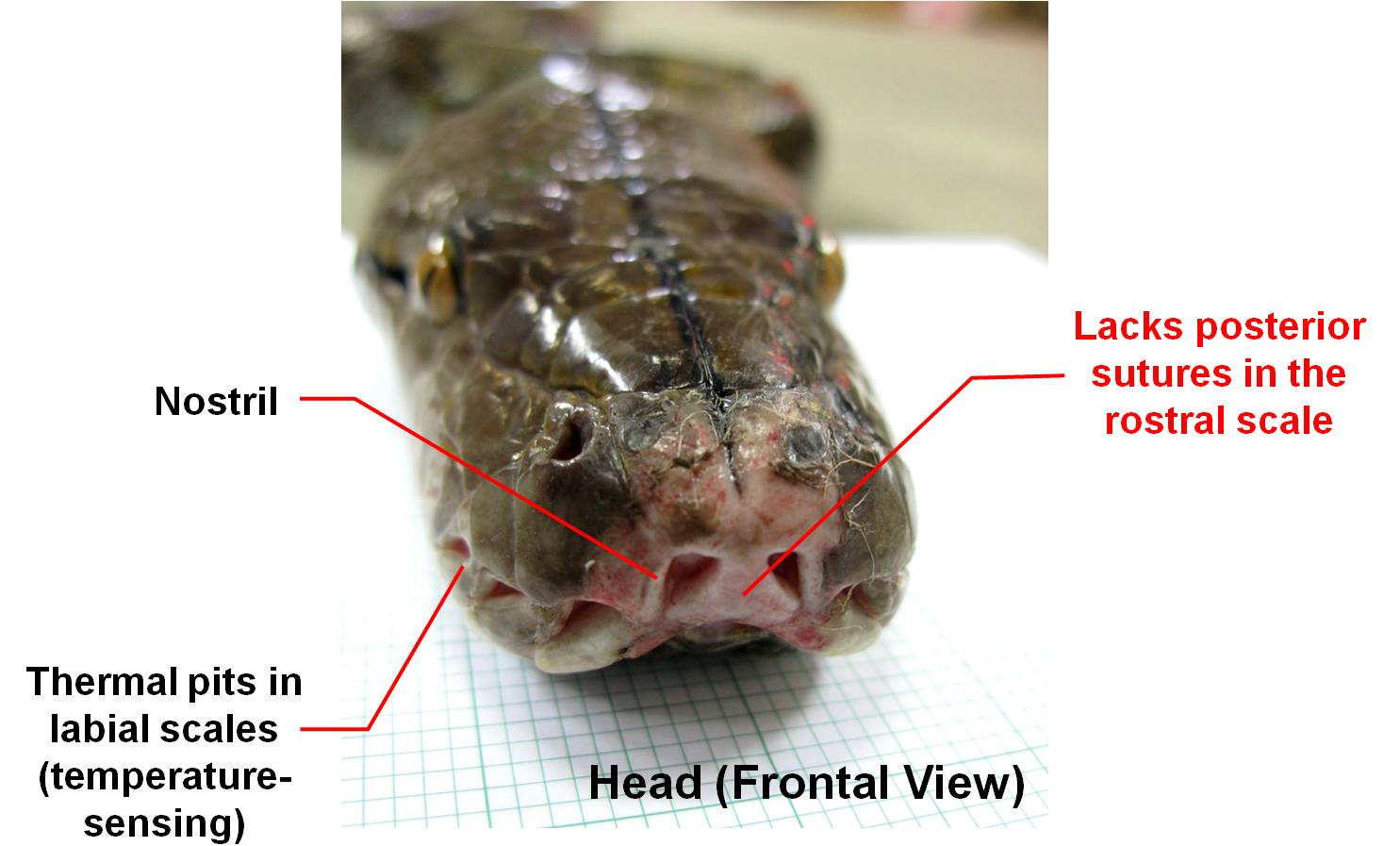

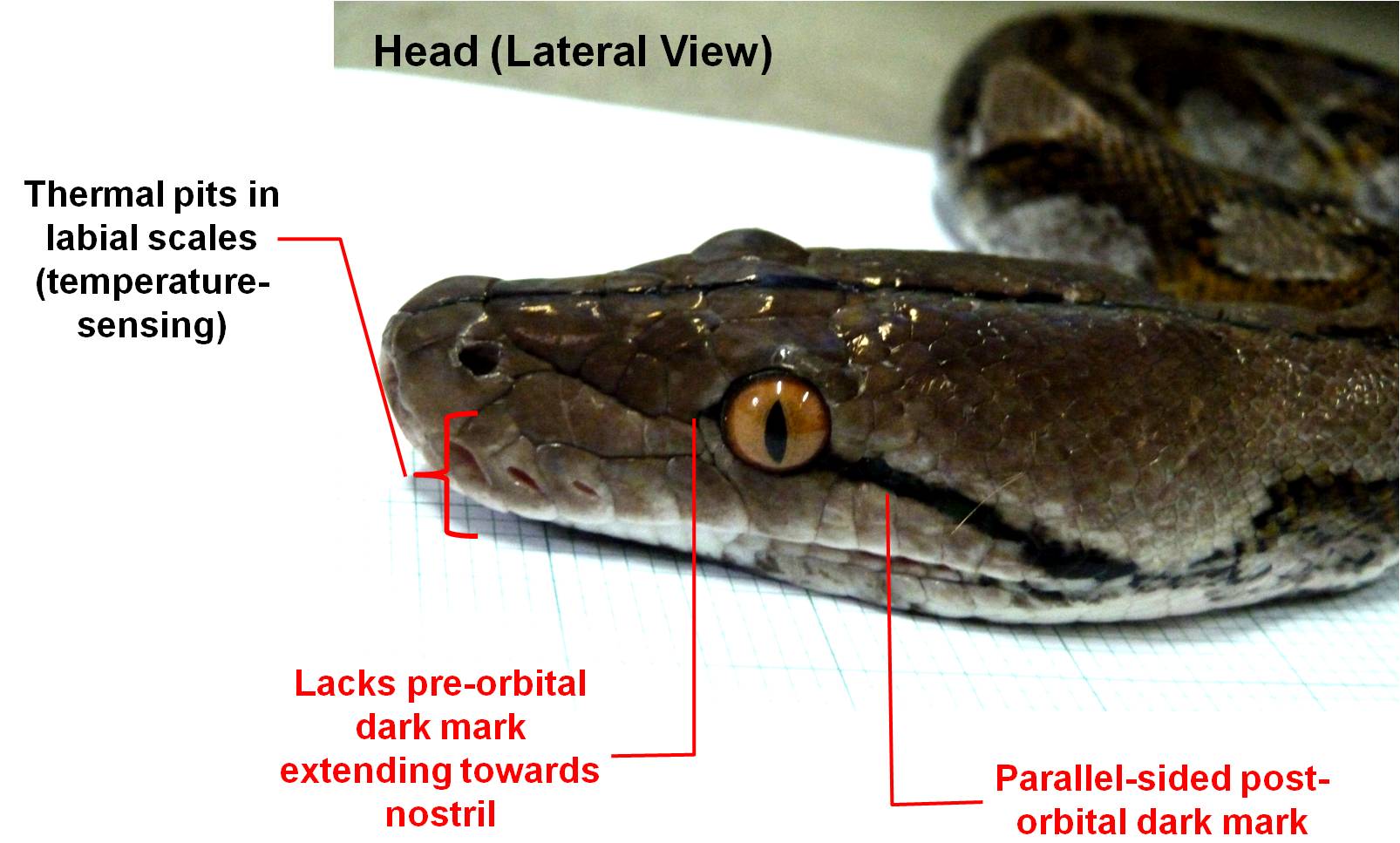

Reticulated pythons are ambush foragers and will often remain immobile but alert for long periods of time when stalking prey. They rely mainly on their visual and olfactory senses, but thermal and vibratory stimuli are also important when hunting [10] . These pythons hunt a wide variety of prey species across a range of taxa but mammals seem the be the most frequent prey choice [11] . They regularly hunt larger prey such as monitor lizards, civet cats, deer and various primates. Feeding behaviour in the captivity is generally very similar, although there is no proper 'hunting' experience. The first video above shows the python's characteristic constricting behaviour when seeking to capture their prey.The body-size of the individual snake is strongly related to the prey choice composition. This can be explained by an ontogenetic shift. Juvenile specimens hunt almost exclusively on rats but have been noted to shift to bigger mammal prey after they reach a length of about 4 m or more [12] . This is in line with the general trend of larger snakes being able to consume larger sized and a greater variety of prey [13] . The feeding habits of reticulated pythons does not seem to vary with the seasons.

PREDATORS

Since reticulated pythons are difficult to study in the wild, the natural range of predators for this species is not known. But evidence suggests that juvenile pythons are susceptible to predation by crocodilians, pigs and birds [14] . Humans also present a distinct threat to the species.OTHER BEHAVIOUR

Anecdotal evidence suggests that these pythons are primarily nocturnal. They have been known to aggregate in tree trunks or under plants, especially in cool weather [15] . The reasons for this aggregation are not clearly understood, but mating activities could be a root cause. Some observations have shown that a P. reticulatus specimen may be found in the same site repeatedly, suggesting that either the species has very sedentary habits or is inclined to familiar places. Reticulated pythons are known to have a 'vicious' disposition but will not usually attack unless provoked. (philopatry). This behaviour can be seen in the second video above.(Return to Table of Contents)

|

|

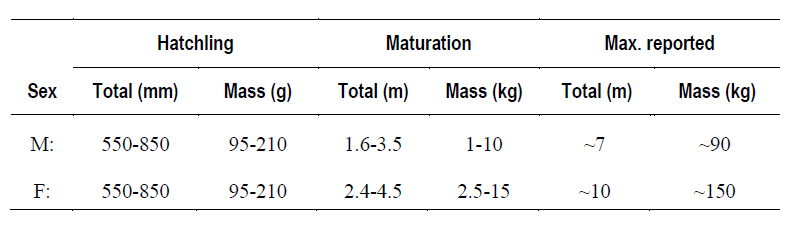

| Total length and masses of a typical reticulated python (Credit: Reed & Rodda, 2009) |

A female reticulated python is measured and weighed at the California Academy of Sciences. |

BODY-SIZE DISTRIBUTIONS

Reticulated pythons have been known to grow up to 10 meters in length and weighing up to 150 kilograms [16] , but this is the rare exception. Individuals caught in the wild are usually 4 meters or shorter [17] . The body-size distribution of the species does show a seasonality; there is a cyclic tendency within individual populations. This is most probably due to the synchronised hatching of the new generation coupled with the exceptionally fast growth rates of juvenile pythons [18] . The table shown above shows the lengths and masses of a typical reticulated python specimen.SEXUAL DIFFERENTIATION

Females reticulated pythons are capable of obtaining a larger maximum size than the males, although males are usually heavier than females of the same body length [19] . This difference in size in relation to gender is called sexual size dimorphism. Predictably, the females also mature at a larger size. But overall, there is insufficient quality data to determine if this dimorphism is reliable in gender identification. Other than size and mass, adult male P. reticulatus usually also have slightly longer tails and larger spurs .REPRODUCTION

P. reticulatus females will typically lay about 20-40 eggs and remain with the clutch for the incubation period of around 55-105 days [20] . The number of eggs produced per clutch is highly dependent on the body-size of the females. Adult females pythons are non-reproductive in most years although they may be physiologically reproductively viable [21] .The reproduction of reticulated pythons is strongly seasonal for both sexes. However, the duration and period of oviposition differs among populations which are geographically separated [22] . This is probably due to differing environmental conditions, especially rainfall intensity, and may be emphasized by human influences. Sexual maturity in P. reticulatus is dependent on the individual reaching a certain body size and length. P. reticulatus has an overall low reproductive frequency which may indicate a lack of food resource and the high survivability of the larger snakes [23] .

(Return to Table of Contents)

The commercial trade of this species is regulated under the Convention of International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) Appendix II. Trade in Appendix II species is controlled, usually by enforcing export quotas, to ensure that the survival of the species is not threatened. Indonesia exports the largest quantities of live P. reticulatus and skins with Malaysia coming in a close second [25] [26] . Many of these are wild-caught species, although breeding farms also contribute greatly to the supply.

|

|

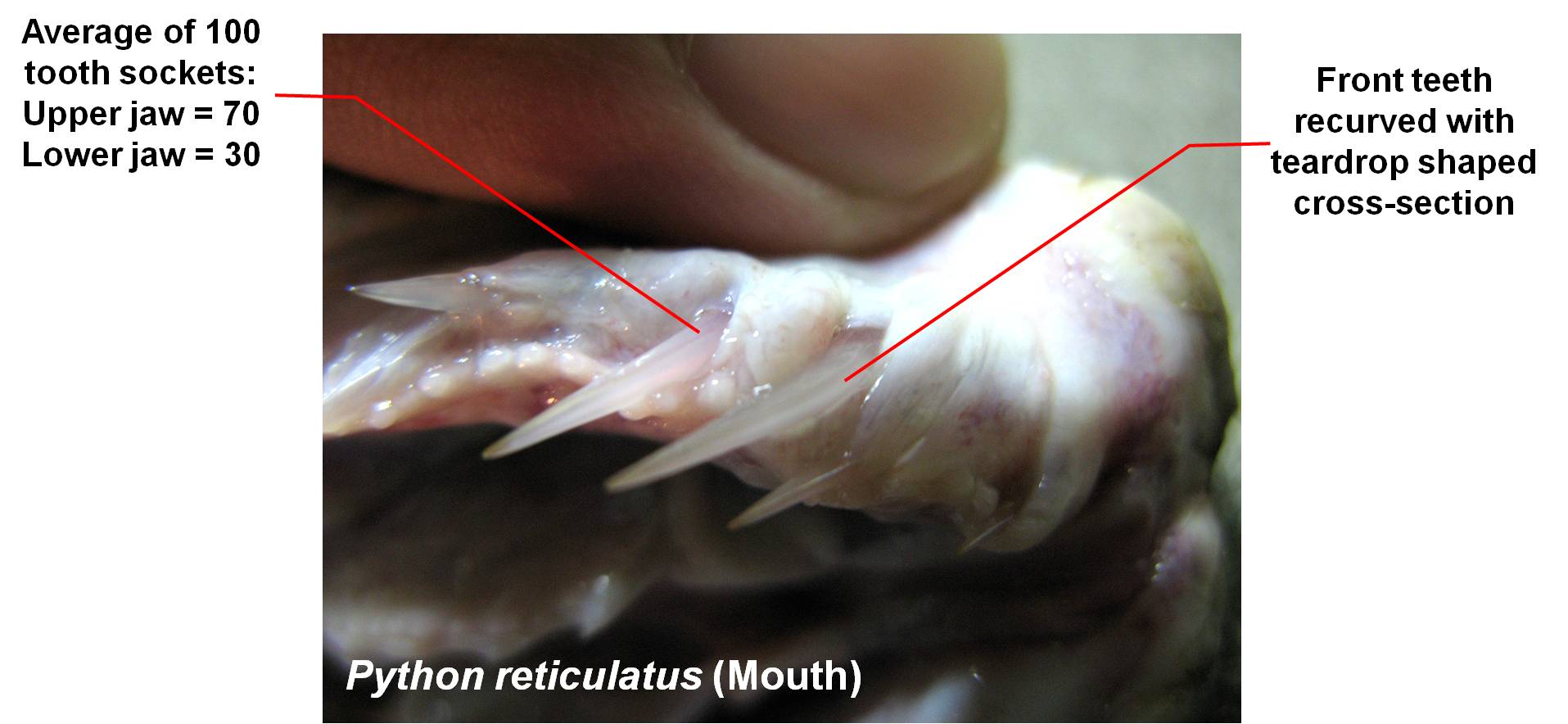

Due to the increasing popularity of these snakes in the pet trade and their establishment in urban areas, human-python interactions are becoming increasingly common. Attacks on humans by wild and 'domesticated' P. reticulatus have been well-documented [27] . When grown to full size, these constrictors are fully capable of causing harm or death to an adult human. The bites of these snakes are not poisonous but can be extremely painful. They have also been known to carry a variety of pathogens that could potentially be harmful to humans.

(Return to Table of Contents)

CITES: Appendix II

IUCN Red List: Not listed

More than 500,000 specimens of Python reticulatus are caught from the wild every year to supply the demand for reptile skins [28] . In 2011, Indonesia alone is set to deliver 157,500 specimens for the commercial leather industry [29] . However, several studies by have concluded that P. reticulatus is unlikely to be local Indonesian populations are unlikely to be extirpated due to the commercial skin trade alone [30] [31] . Still, the wild population numbers should be carefully monitored since the sustainability of commercial trade in this species is largely unknown.

P. reticulatus is not listed under the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species. The three species of snakes of the genus Python already listed in the IUCN Red List (Python anchietae, Python molurus, Python regius) were all threatened by the booming pet trade industry (IUCN, 2011). No species under the genus Broghammerus is listed in the Red List.

(Return to Table of Contents)

(Return to Table of Contents)

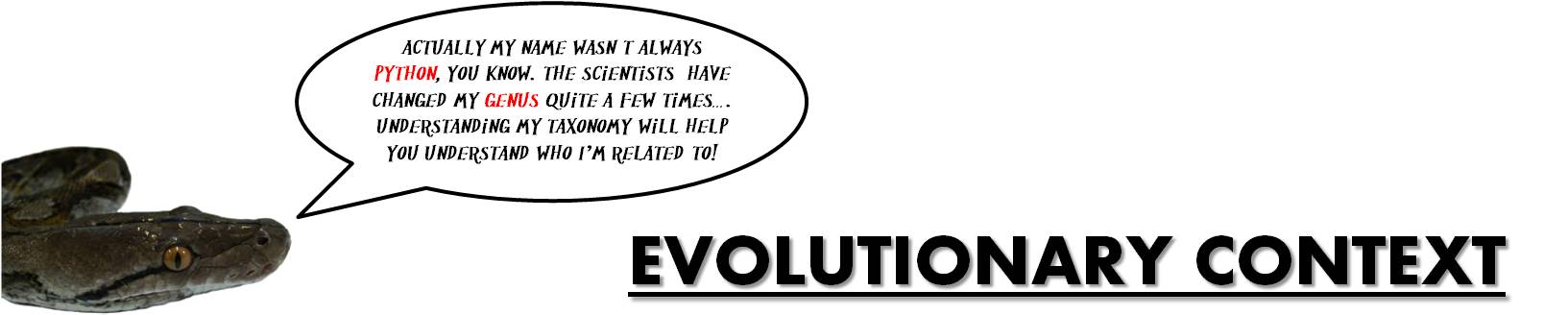

|

| Simplified phylogenetic tree showing the relationship between the genus Python and other related genus. |

Schneider, in 1801, first placed the python under the genus Boa, making the original name Boa reticulatus. This classification was used because Schneider assumed that this particular species was in close resemblance and relation to other species such as the Boa rhombeata and Boa carinata (now Candoia carinata Böhme et al., 1998). But further studies proved that these species were not as closely related as first assumed. Thus in the 20th century, the constrictor was reclassified under the genus Python [37] [38] .

More recent phylogenetic studies have discovered that there is a prominent distinction between species within the genus Python itself [39] . Taxonomic studies using morphological characteristics as well as mitochondrial genes have showed that P. reticulatus and P. timoriensis (Lesser Sunda Python) are sufficiently different from the other seven known python genera from Australia and New Guinea to form a different clade. This would mean that the P. reticulatus and P. timoriensis are sister species within a paraphyletic Python genus [40] . This simplified phylogenetic tree shows how the genus Python is split. The distinction between 'Afro-Asian' and 'Indo-Australian' refers to the inferred biogeographical origins of the species.

Thus, there is a push to reclassify both P. reticulatus and P. timoriensis under the genus Broghammerus. This clade differentiation is generally accepted and the name Broghammerus reticulatus is being increasingly utilised by scientists in their work. The alternative solution to this reclassification would be to combine all the Australian and Asian python species into the Python genus. However this method was not supported by many since the phylogenetic evidence is sufficient to support a clade differentiation and the genus Broghammerus is already firmly established.

(Return to Table of Contents)

| Neotype: ZFMK 32378, subadult |

| Type Locality: Rengit, West Malaysia, 1980 |

| Description of Neotype: Total Length = 130.8 cm; Snout-Vent Length = 113.5 cm; Tail Length = 17.3 cm. |

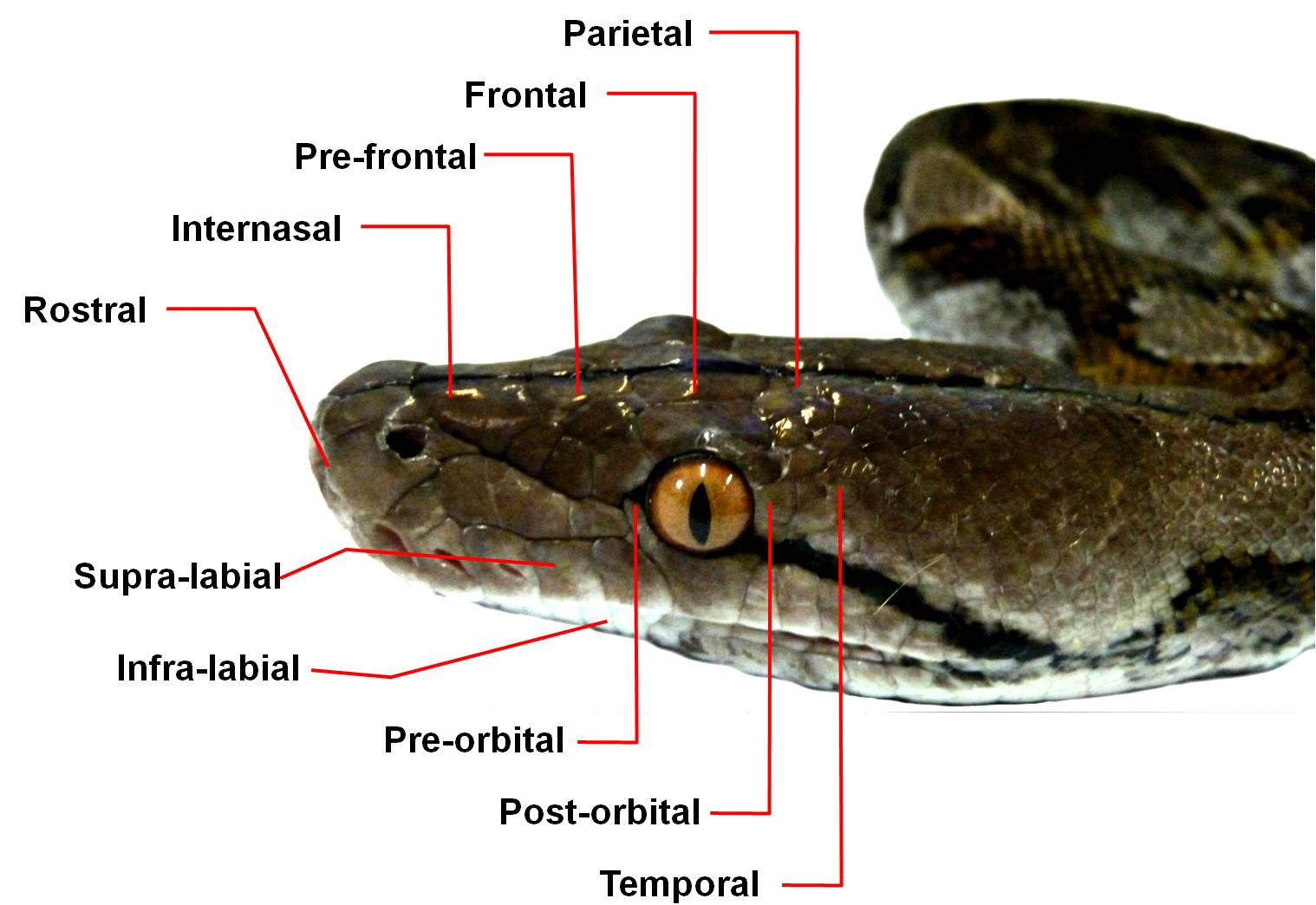

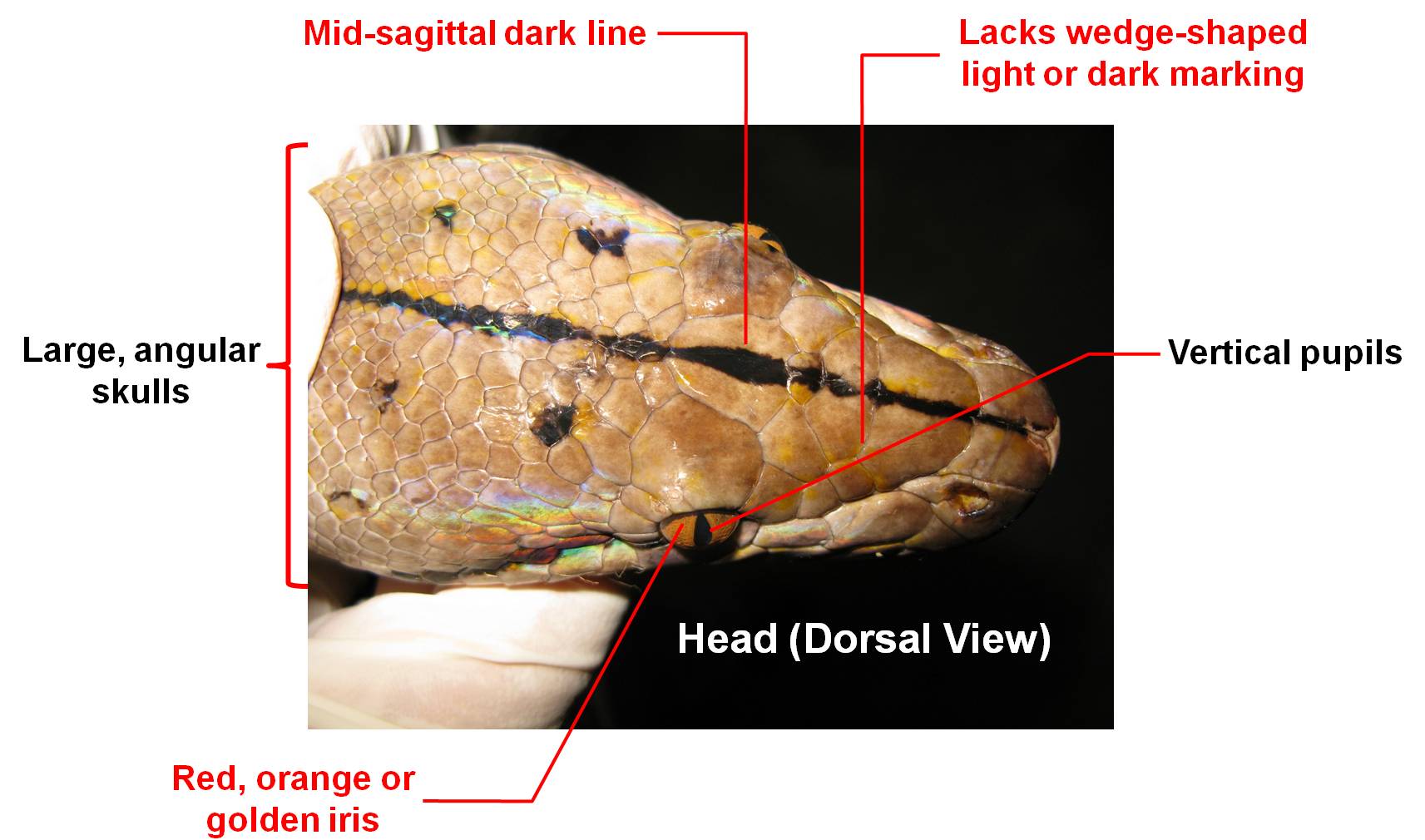

| “Irregular black network forming squared figures dorsally; laterally white blotches framed by two black flecks; two black zigzag-lines, lower less distinct visible on flanks; ground color between lateral markings brown or gray; ventrum yellow to white, some ventrals edged dark; tail darker; head ground color brown; black median streak beginning at rostrum ending in the nape region; distinct black dot on either side of parietal region; head laterally marked with black streak on both sides. 313 ventrals; 92 subcaudals; 58 dorsals anteriorly, 72 at midbody, 37 posteriorly; anal single; rostral scale with 2 diagonal pits; 1 pair of internasals in contact with nasals; 1 pair of anterior prefrontals; 10 posterior prefrontals in two rows; 2 large supraoculars; 1 undivided frontal; 4 distinct parietals separated by 2 pairs of smaller interparietals; 13 supralabials (1–4 pitted), the 7th entering orbit; 2 preoculars and 4 postoculars on both sides; 5 loreals on left side, and 4 on right; 21 infralabials on left, 22 on right side (scales 13–18 on right side and 12–16 on left side pitted).”[43] |

Further information on type specimens can be found at the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) .

(Return to Table of Contents)

(Return to Table of Contents)

(Return to Table of Contents)

- ^ Reed, R.N., Rodda, G.H. (2009). Giant constrictors: biological and management profiles and an establishment risk assessment for nine large species of pythons, anacondas and the boa constrictor, U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 009-1202, 302 p.

- ^ Auliya, M., Mausfeld, P., Schmitz, A., Böhme, W. (2002). Review of the reticulated python (Python reticulatus Schneider, 1801) with the description of new subspecies from Indonesia. Naturwissenschaften, 89:201-213

- ^ Hoser, R. (2003) A Reclassification of the Pythoninae Including the Descriptions of Two New Genera, Two New Species, and Nine New Subspecies. Part I. Crocodilian 4(3):31-37

- ^ Hoser, R.T. (2004) A reclassification of the Pythonidae including the descriptions of new genera, two new species and nine new subspecies. Continued. Crocodilian – Journal of the Victorian Association of Amateur Herpetologists 4:21-39

- ^ Shine, R., Harlow, P.S., Keogh, J.S., Boeadi (1998b). The influence of sex and body size on food habits of a giant tropical snake, Python reticulatus, Functional Ecology, 12:248-258

- ^ Reed, R.N., Rodda, G.H. (2009). Giant constrictors: biological and management profiles and an establishment risk assessment for nine large species of pythons, anacondas and the boa constrictor, U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2009-1202, 302 p.

- ^ Auliya, M., (2006) Taxonomy, life history and conservation of giant reptiles in West Kalimantan (Indonesian Borneo): Munich, Natur und Tier Verlag, 432 p.

- ^ David, P., Vogel, G., (1996) The snakes of Sumatra: an annotated checklist and key with natural history notes: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, Edition Chimaira, 260 p.

- ^ Shine, R., Harlow, P.S., Keogh, J.S., Boeadi (1998a). The allometry of life history traits: insights from a study of giant snakes (Python reticulatus), Journal of Zoology London, 244:405-414

- ^ Reed, R.N., Rodda, G.H. (2009). Giant constrictors: biological and management profiles and an establishment risk assessment for nine large species of pythons, anacondas and the boa constrictor, U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2009-1202, 302 p.

- ^ Shine, R., Harlow, P.S., Keogh, J.S., Boeadi (1998b). The influence of sex and body size on food habits of a giant tropical snake, Python reticulatus, Functional Ecology, 12:248-258

- ^ Shine, R., Harlow, P.S., Keogh, J.S., Boeadi (1998b). The influence of sex and body size on food habits of a giant tropical snake, Python reticulatus, Functional Ecology, 12:248-258

- ^ Arnold, S.J. (1993) Foraging theory and prey-size-predator-size relations in snakes. Snakes. Ecology and Behaviour, McGraw-Hill New York, pp. 87-116

- ^ Reed, R.N., Rodda, G.H. (2009). Giant constrictors: biological and management profiles and an establishment risk assessment for nine large species of pythons, anacondas and the boa constrictor, U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2009-1202, 302 p.

- ^ Reed, R.N., Rodda, G.H. (2009). Giant constrictors: biological and management profiles and an establishment risk assessment for nine large species of pythons, anacondas and the boa constrictor, U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2009-1202, 302 p.

- ^ Zug, G.R., and Ernst, C.H., 2004, Smithsonian answer book: snakes: Washington, D.C., Smithsonian Books, 177 p.

- ^ Auliya, M., (2006) Taxonomy, life history and conservation of giant reptiles in West Kalimantan (Indonesian Borneo): Munich, Natur und Tier Verlag, 432 p.

- ^ Shine, R., Harlow, P.S., Keogh, J.S., Boeadi (1998a). The allometry of life history traits: insights from a study of giant snakes (Python reticulatus), Journal of Zoology London, 244:405-414

- ^ Reed, R.N., Rodda, G.H. (2009). Giant constrictors: biological and management profiles and an establishment risk assessment for nine large species of pythons, anacondas and the boa constrictor, U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2009-1202, 302 p.

- ^ Reed, R.N., Rodda, G.H. (2009). Giant constrictors: biological and management profiles and an establishment risk assessment for nine large species of pythons, anacondas and the boa constrictor, U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2009-1202, 302 p.

- ^ Shine, R., Harlow, P.S., Keogh, J.S., Boeadi (1998a). The allometry of life history traits: insights from a study of giant snakes (Python reticulatus), Journal of Zoology London, 244:405-414

- ^ Shine, R., Ambariyanto, Harlow, P.S., Mumpuni (1999). Reticulated pythons in Sumatra: biology, harvesting and sustainability, Biological Conservation, 87:349-357

- ^ Shine, R., Harlow, P.S., Keogh, J.S., Boeadi (1998a). The allometry of life history traits: insights from a study of giant snakes (Python reticulatus), Journal of Zoology London, 244:405-414

- ^ Shine, R., Ambariyanto, Harlow, P.S., Mumpuni (1999). Reticulated pythons in Sumatra: biology, harvesting and sustainability, Biological Conservation, 87:349-357

- ^ Auliya, M., Mausfeld, P., Schmitz, A., Böhme, W. (2002). Review of the reticulated python (Python reticulatus Schneider, 1801) with the description of new subspecies from Indonesia. Naturwissenschaften, 89:201-213

- ^ UNEP-WCMC. (May 2011) Retrived 1 November, 2011. UNEP-WCMC Species Database: CITES-Listed Species from http://www.unep-wcmc-apps.org/isdb/CITES/Taxonomy/tax-species-result.cfm/isdb/CITES/Taxonomy/tax-species-result.cfm?displaylanguage=eng&Genus=Python&Species=reticulatus&source=animals&Country=

- ^ Reed, R.N., Rodda, G.H. (2009). Giant constrictors: biological and management profiles and an establishment risk assessment for nine large species of pythons, anacondas and the boa constrictor, U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2009-1202, 302 p.

- ^ Shine, R., Ambariyanto, Harlow, P.S., Mumpuni (1999). Reticulated pythons in Sumatra: biology, harvesting and sustainability, Biological Conservation, 87:349-357

- ^ UNEP-WCMC. (May 2011) Retrived 1 November, 2011. UNEP-WCMC Species Database: CITES-Listed Species from http://www.unep-wcmc-apps.org/isdb/CITES/Taxonomy/tax-species-result.cfm/isdb/CITES/Taxonomy/tax-species-result.cfm?displaylanguage=eng&Genus=Python&Species=reticulatus&source=animals&Country=

- ^ Groombride, B., Luxmoore, R. (1991) Pythons in south-east Asia. A review of distribution, status and trade in three selected species, Report to CITES Secretariat, Laussane, Switzerland

- ^ Shine, R., Ambariyanto, Harlow, P.S., Mumpuni (1999). Reticulated pythons in Sumatra: biology, harvesting and sustainability, Biological Conservation, 87:349-357

- ^ Baker, N., Lim, K. (2008) Wild animals of Singapore: A photographic guide to mammals, reptiles, amphibians and freshwater fishes, Draco Publishing, Singapore

- ^ Chou, L.M. (1988) Snake encounters in the urban environment, The Pangolin, Malayan Nature Society (Singapore Branch), 1(3)

- ^ Subharaj, R.(1999) Pythons galore!, The Pangolin, Malayan Nature Society (Singapore Branch), 2(2)

- ^ STOMP This Urban Jungle: Python crushes cat to death at Bukit Panjang. Retrieved on 12 November 2011 from http://singaporeseen.stomp.com.sg/stomp/sgseen/this_urban_jungle/661846/python.html

- ^ STOMP This Urban Jungle: Spotted at Lower Pierce: Python that's longer than the height of 3 grown men. Retrieved on 12 November 2011 from http://singaporeseen.stomp.com.sg/stomp/sgseen/this_urban_jungle/775090/spotted_python_thats_longer_than_the_height_of_3_grown_men.html

- ^ Underwood, G., Stimson, A.F. (1990) A classification of pythons (Serpentes, Pythonidae), Journal of Zoology 221:565-603

- ^ Kluge, G. (1993) Aspidetes and the phylogeny of pythonine snales, Rec Aust Mus 19:1-77

- ^ Hoser, R.T. (2004) A reclassification of the Pythonidae including the descriptions of new genera, two new species and nine new subspecies. Continued. Crocodilian – Journal of the Victorian Association of Amateur Herpetologists 4:21-39

- ^ Rawlings, L.H., Rabosky, D.L., Donnellan S.C., Hutchinson, M.N. (2008). Python phylogenetics: inference from morphology and mitochondrial DNA, Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 93:603-619

- ^ Stimson, A.F. (1969) Das tierreich: Lister der rexenten Amphibian und Reptilien. Boidae (Boinae + Bolyeriinae + Loxoceminae + Pythoninae). Walter de Gruyter, Berlin

- ^ Böhme, W., Bischoff, W. (1984) Amphibien und reptilien, In: Rheinwald G. (ed.) Die Wirbeltiersammlungen des Museums Alexander Koenig. Bonn Zool Monogr 19:151-213

- ^ Auliya, M., Mausfeld, P., Schmitz, A., Böhme, W. (2002). Review of the reticulated python (Python reticulatus Schneider, 1801) with the description of new subspecies from Indonesia. Naturwissenschaften, 89:201-213

_GBIF Data Portal Sources:_

Arctos, MVZ Herp Catalog (accessed through GBIF data portal,http://data.gbif.org/datasets/resource/8123, 2011-11-16)

California Academy of Sciences, CAS Herpetology Collection Catalog (accessed through GBIF data portal,http://data.gbif.org/datasets/resource/161, 2011-11-16)

Comisión nacional para el conocimiento y uso de la biodiversidad, Colección científica del Museo de Historia Natural Alfredo Dugés (accessed through GBIF data portal,http://data.gbif.org/datasets/resource/13368, 2011-11-16)

Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, MCZ Herpetology Collection (accessed through GBIF data portal,http://data.gbif.org/datasets/resource/12031, 2011-11-16)

Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, MCZ Herpetology Collection - Reptile Database (accessed through GBIF data portal,http://data.gbif.org/datasets/resource/578, 2011-11-16)

National Museum of Natural History, NMNH Vertebrate Zoology Herpetology Collections (accessed through GBIF data portal,http://data.gbif.org/datasets/resource/1838, 2011-11-16)

Natural History Museum, University of Oslo, Herpetile collection, Natural History Museum, University of Oslo (accessed through GBIF data portal,http://data.gbif.org/datasets/resource/8103, 2011-11-16)

OZCAM (Online Zoological Collections of Australian Museums) Provider, Australian Museum provider for OZCAM (accessed through GBIF data portal,http://data.gbif.org/datasets/resource/9105, 2011-11-16)

OZCAM (Online Zoological Collections of Australian Museums) Provider, Western Australia Museum provider for OZCAM (accessed through GBIF data portal,http://data.gbif.org/datasets/resource/9113, 2011-11-16)

Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research, Herp Collection (accessed through GBIF data portal,http://data.gbif.org/datasets/resource/1939, 2011-11-16)

Royal Ontario Museum, Herp specimens (accessed through GBIF data portal,http://data.gbif.org/datasets/resource/659, 2011-11-16)

Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde Stuttgart, Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde Stuttgart (accessed through GBIF data portal,http://data.gbif.org/datasets/resource/11127, 2011-11-16)

United States Geological Survey, USGS Nonindigenous Aquatic Species database (accessed through GBIF data portal,http://data.gbif.org/datasets/resource/13087, 2011-11-16)

University of Kansas Biodiversity Research Center, Herpetology Collection (accessed through GBIF data portal,http://data.gbif.org/datasets/resource/982, 2011-11-16)