|

| Rana (Lithobates) catesbeiana (Shaw, 1802); American Bullfrog.<Photo taken by Ip Yin Cheong Aden> |

Table of Contents

- Bullfrogs can leap up to 10x body length (2 meters)

- Weigh up to 1 kg [1]

- Adults can grow up to 18 centimeters in length (excludes legs)

- Longest lifespan : 16 years in captivity, 10 years in the wild

- Calls excessively when thunderstorm approaches

- Food delicacy : Juicy and meaty hind legs

- Asian dessert : Dried fatty tissues of frog's ovaries have anti-aging properties (Hasma or Oviductus ranae) [2]

- Major invasive species originating from North America

- Resistant to lethal amphibian fungal infection (chytridiomycosis) [3]

- Efficient carrier of 'chytridiomycosis-causing fungus' (Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis) [4]

Introduction

- Largest frog species in Singapore

- Aquatic frog, belonging to the family 'true frogs' (Ranidae)

- Bulk of Rana (Lithobates) catesbeiana population is with the commercial breeding company (Jurong frog farm)

- Reared and exported the frogs as food

- Increase sightings of Rana (Lithobates) catesbeiana in Singapore's water catchment areas [5] .

Etymology

The genus name 'Rana' is a Latinized word meaning frog, is a proposed genus name by George Shaw in 1802[6] . However in 2006, John S. Frost replaced the genus to 'Lithobates' [7] , which is a combination of two Greek words 'λίθος' and 'βαίνω'. The word 'λίθος' stands for gemstone, while the word 'βαίνω' stands for walk. The species name 'catesbeiana' is to honor Mark Catesby who was a famous English naturalist who first discovered the bullfrog. The later revision by Green (2007) of the species name [8] 'catesbeianus' is a new Latin patronym for Mark Catesby.Physical Traits

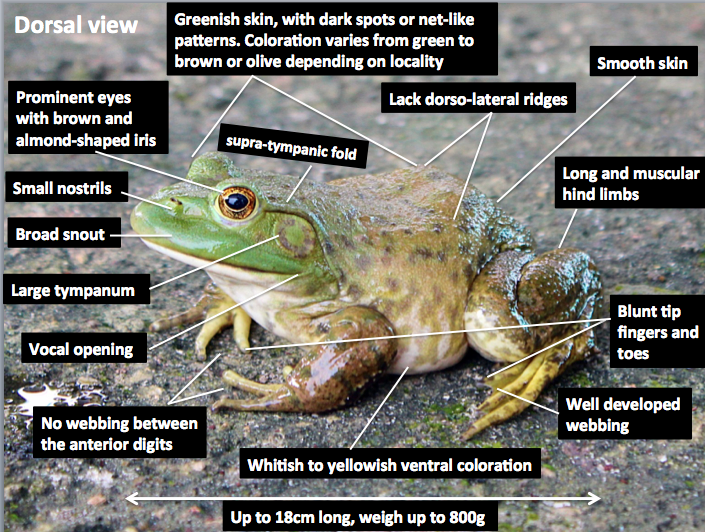

Adults

|

| <Photo taken by Ip Yin Cheong Aden> |

|

| <Photo taken by Ip Yin Cheong Aden> |

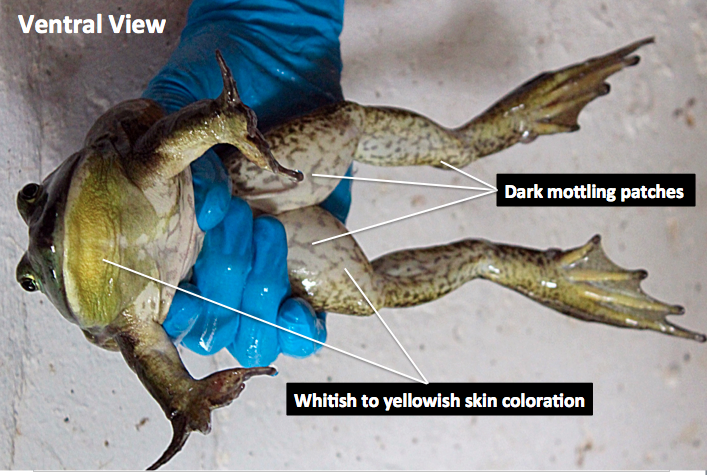

Overall body

- Smooth and non-warty skin

- Absence of dorso-lateral ridges

- Adult dorsal coloration range from greenish, to yellowish or olive-blackish.

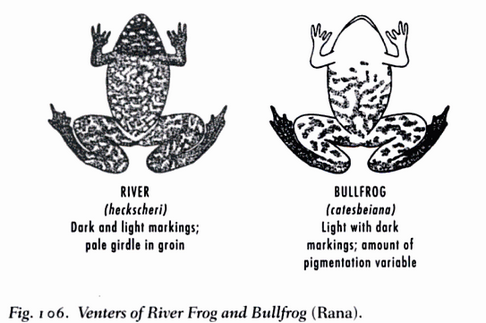

- Ventral coloration is usually whitish or yellowish accompanied with dark mottling patches.

- Head usually a lighter shade of green, with its legs being darkly blotched or banded

- General coloration varies widely according to habitat/location [9]

Limbs

- Long and muscular hind legs

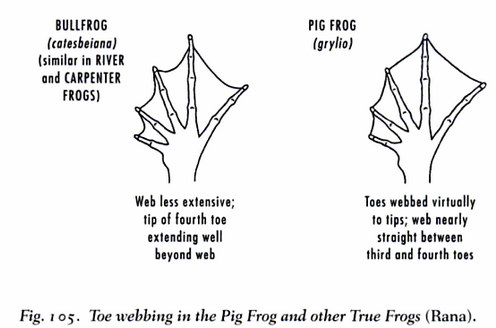

- Well developed webbing in between the toes of hind feet

- Anterior limbs are much shorter than the hind legs and are used to prop the frog's posture up tall.

- No webbing is seen between the fingers of the anterior limbs

- Both the tips of the frog's fingers and toes are blunt [10]

Head

- Broad snout

- Small nostrils are situated near the tip of the snout

- Teeth in its upper jaw

- Vocal openings at the corner of the mouth [11] Large eardrums (tympanums)

- Supra-tympanic fold just above the tympanum, starting from the eye and past the eardrum and finally extending towards its anterior limbs.

- Prominent eyes that are situated above the head unlike the tadpoles which have eyes on the sides of their heads

- Almond-shaped horizontal pupils and brown irises.

Diagnosis

General diagnostic traits for comparison with other frog species :- True frog appearance

- Smooth skin

- Webbed feet

- Long hind legs that represent about half its body length and 40% of its body weight.

- Deep and resonant mating call that resembles the moo of the cow [12] (hence its vernacular name, the American bullfrog.)

Rana catesbeiana calling in a mating pond

Distinct traits for comparison with closely-related ranid frog species :

- Large tympanums

- Prominent supra-tympanic folds

- Lack of dorso-lateral ridges [13]

*The tympanums are the circular eardrums that are situated right behind each eye of the frog.

Sexual Dimorphism

|

| Tympanum size difference between males and females (Costa et al., 1998a,b). <Photo taken by Ip Yin Cheong Aden> |

|

| Ventral throat color difference between males and females (Costa et al., 1998a,b). <Photo taken by Ip Yin Cheong Aden> |

| Trait of comparison |

Male Bullfrog |

Female Bullfrog |

| Time to reach sexual maturity |

1 to 2 years |

2 to 3 years [14] |

| Average snout to vent length |

152 mm |

162 mm [15] |

| Tympanum size |

Twice the size of eye |

Same size as eye |

| Ventral throat coloration |

Yellowish |

Whitish |

| Pigmented nuptial pads |

Present |

Absent |

| Additional notes |

- |

Retain some juvenile color and morphology [16] |

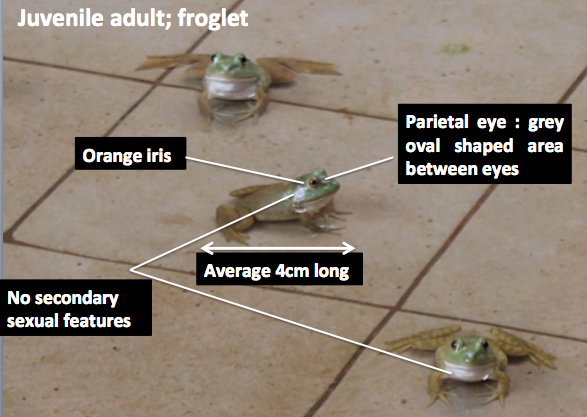

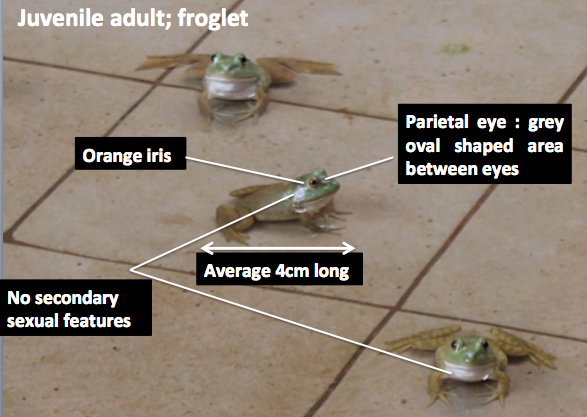

Juvenile Adults

<Photo taken by Ip Yin Cheong Aden>

Juvenile adults or frog-lets are the intermediate transition phase of the metamorphosed tadpoles that have re-absorbed their gills and finned tails. They are miniatures of adult bullfrogs.

- Average 4 cm from snout to vent

- Do not have sexually dimorphic characteristics yet [17]

- Orange irises in their eyes [18]

- Possess a grey oval shaped skin area between their eyes which is called the parietal eye [19]

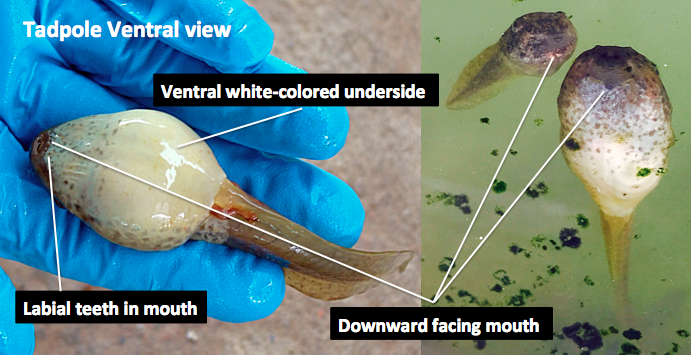

Larvae (Tadpoles)

|

| <Photo taken by Ip Yin Cheong Aden> |

- Tadpoles are also very large by frog standards, 8cm to 15cm [20]

- Long, muscular tail with broad dorsal and ventral fins

- Downward-facing mouths

- Dorsal coloration is brown to light olive with small black spots scattered across the head and upper body.

- Ventral side is usually whitish to yellowish in color.

- Initially have three pairs of external gills, and several rows of labial teeth [21]

- Unlike the adult frogs, tadpoles have their eyes at the sides of their heads with orange irises

As they grow, they begin to ingest larger particles and use their teeth for rasping.

Growth of hind legs are usually observed before the anterior limbs bud out while the tadpole metamorphoses into a frog-let [22]

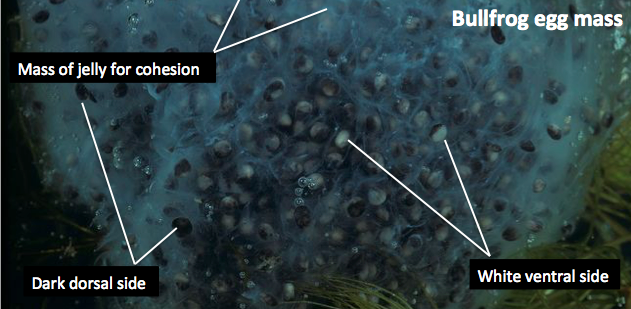

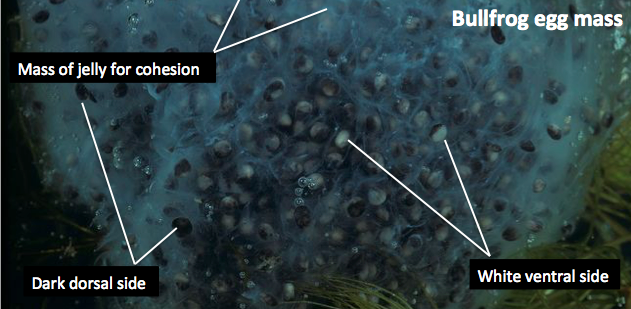

Eggs

Copyright Phil Dengginger; Arkive; Obtained with permission.

- Very small

- Dorsal black color

- Slightly lighter or whitish ventral underside

- Each egg is surrounded by a jelly capsule

- Additional jelly that creates a loose cohesion to the entire mass of eggs

- About 10,000 to 20,000 eggs are usually laid near the water surface in one brood [23]

Biology

General behavior [24]| Trait |

Adults |

Larvae |

| Activity |

Principally nocturnal, though observed to be active throughout the day |

Principally nocturnal, though observed to be active throughout the day |

| Residing environment |

Semi aquatic and terrestrial |

Fully aquatic |

| Feeding type |

Carnivorous |

Herbivorous |

| Muscular hind legs / tail |

Used to leap for prey, grasp females or simply for escaping [25] |

Used to support and maneuver its huge body in water |

Types of defensive behavior

Mature male Rana (Lithobates) catesbeiana are extremely territorial animals. The male frogs do not hesitate in attacking a competitor or intruder of their turf, with rapid kicking, leaping and grappling.Rana (Lithobates) catesbeiana have large mouths with a row of teeth in the upper jaw, rendering it capable of inflicting painful bites onto unsuspecting targets. The small teeth on its upper jaw are effective tools to help the bullfrogs to grab it prey as well.

- Vocalization for Defense

Rana catesbeiana distress call <at 0.16 of video>

Mating Behavior

- Males are extremely territorial

- Occupy sites that are usually spaced 3 to 6 meters from the next frog and call loudly [27]

- Males make different types of calls, such as territorial calls to warn other males [28]

- Males make advertisement calls to attract females [29]

|

| Mating pair of bullfrogs on the right, engaged in the amphiplexus position<Photo taken by Ip Yin Cheong Aden> |

Habitat and Reproductive cycle

Rana (Lithobates) catesbeiana can thrive in a wide range of environmental conditions since they are a species of frogs that easily adapt to the environment. They are found in both temperate where they hibernate over winter, as well as tropical regions where temperatures can go up to 40 °C[32] .The duration of the breeding season is influenced by the amount of sunlight, temperature, atmospheric pressure and humidity. The closer Rana (Lithobates) catesbeiana is to the equator, the longer its reproductive period through the year . It has been observed that Rana (Lithobates) catesbeiana breeds all year round in Singapore, but only have a three-month breeding season in North America.

Once the eggs are laid, the development of embryos is determined by temperature, whereby larvae will hatch within 48 hours in warmer conditions above 26 °C. Egg masses are laid near the water surface for facilitation of oxygen diffusion into eggs. Larvae are about 10mm long, attach to smooth surfaces and consume their yolk sac within 72 hours [33] . After the yolk sac has been emptied, the larvae become free swimming and filter feeding tadpoles.

|

| Rana (Lithobates) catesbeiana froglet prior to tail resorption<Photo taken by Ip Yin Cheong Aden> |

Larvae

- Hatch in about 4 days to be fully aquatic and gilled tadpoles

- Tadpole stage may persist for up to 2 years

- The longer the time taken for a tadpole to metamorphose, the larger the adult would be

- Competitive interaction; includes predator, inter and intraspecific interactions

- Environmental conditions; food availability, temperature, water quality

Adults

- After one or two years, tadpoles metamorphose into adults

- Reproduction occurs in permanent water bodies (In Singapore since its warm all year round, breeding season is all year, especially after episodes of heavy rainfall)

- Males attract females by calling (a deep, hoarse "ba-rum" or "jug-o-rum")

Rana (Lithobates) catesbeiana calling and mating

- Mating occurs in water; males clasp females and hold them in amphiplexus

- Females release eggs while in amphiplexus; eggs are surrounded by a gelatinous sheet that adheres to vegetation [34]

- Fertilization is external

- Average lifespan of adults is about 6 years [35]

Diet

- Adults usually ambush its unsuspecting prey by sitting quietly

- As the prey passes by, it lunges forward with a wide open mouth, powered by its powerful hind legs.

- The bullfrog eats and swallows practically anything that can fit into their mouths.

- They have a wide range of prey, from insects to mice, fish, birds, herpetofauna (snakes and turtles) and even its own kind (cannibalism) [36] .

American bullfrogs eat anything that fits into its mouth!

- Bullfrog tadpoles mostly graze on aquatic plants, or eat suspended matter, organic debris, algae, plant tissue, and small aquatic invertebrates [37]

- During metamorphosis, diet gradually shift towards ingesting animal protein

- Fully carnivorous after tail resorption in the froglets [38]

- A day in the life of a bullfrog tadpole

Distribution

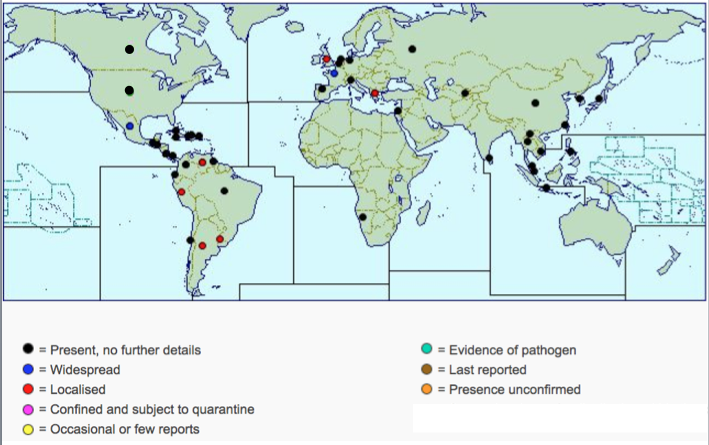

Global

Singapore

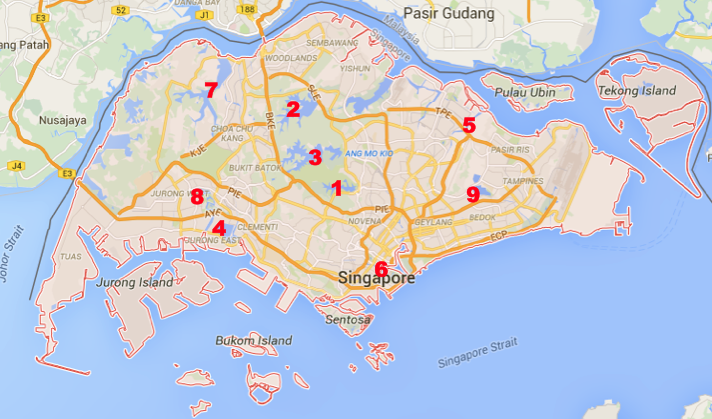

|

| American bullfrogs sighted in Singapore water catchment with corresponding number labels of reservoirs (Author's modification from Google Maps) |

*The objective of this map is to allow the general public to mark out the places where they have spotted the American bullfrogs in Singapore. This would aid in monitoring and assessment of the spread of this invasive frog species with respect to local ecosystems, native anuran species richness and ecological balance.

The American bullfrog is locally found in the water catchment areas as well as drains, canals and park connectors[40]

Sighted in:

- Macritchie Central Catchment (Most sighted)

- Seletar reservoir

- Peirce reservoir

- Pandan reservoir

- Punggol reservoir

- Marina reservoir

- Kranji reservoir

- Jurong lake

- Bedok reservoir

Invasive Species Implications

|

| Frog farm containment walls are only as high as 1 meter; bullfrogs may escape by leaping over walls <Photo taken by Ip Yin Cheong Aden> |

- Imported into Singapore since American bullfrog legs are a profitable and marketable consumable food commodity

- Easily cultivated but also difficult to contain as they are very prone to escaping (leaps up to 2 meters)

- Used in aquatic pet trade as baits or food for the Arowana fish (F. Osteoglossidae)

- Accidental release or escapes result in thriving populations with thousands of bullfrogs within a year of colonization arising from just one successful spawning event [41] .

|

| An escaped or released American bullfrog spotted in one of the local waterways <Photo taken by Ip Yin Cheong Aden> |

- They are highly adaptable to new environments and are large, opportunistic predators that out-competes native anurans.

- Larvae rapidly eat algae especially in nutrient poor ponds, monopolizing primary production and upset aquatic community structure [42]

- The American Bullfrog is resistant to Chytridiomycosis and hence is a well known vector for transmitting this deadly amphibian disease.

- The chytrid fungus, Batarachochytrium dendrobatidis, causes the disease that has wiped out many anuran species thus far [43]

- Listed as the top 100 most devastating invasive species by the Global Invasive Species Database [44]

- DO NOT release your pet American bullfrogs, prevent the bullfrog baits and commercially farmed frogs from escaping into our local ecosystem!

Taxonomy

Taxonavigation

- Domain: Eukaryota

- Kingdom: Metazoa

- Phylum: Chordata

- Subphylum: Vertebrata

- Class: Amphibia

- Subphylum: Vertebrata

- Phylum: Chordata

- Kingdom: Metazoa

Names

- Binomial: Rana catesbeiana (Shaw, 1802)[50]

- Vernacular: American bullfrog, Common bullfrog, Edible bullfrog, Eastern bullfrog, Jug-'O'-rum, Bloody nouns

- Synonyms:

- Rana catesbeiana, Rana (Lithobates) catesbeiana (Shaw, 1802)[51]

- Rana (Rana) catesbeiana (Boulenger, 1920; Dubois, 1978)

- Rana catesbyana (Smith, 1978)

- Rana (Aquarana) catesbeiana (Dubois, 1992)

- Rana (Novirana, Aquarana) catesbeiana (Hillis and Wilcox, 2005)[52]

- Lithobates catesbeianus (Frost et al., 2006)[53]

- Lithobates (Aquarana) catesbeianus (Dubois, 2006)

Which name do we use?

This frog species was shifted by [54] into the genus Lithobates based on extensive sequence data, which is highly debatable because if Lithobates catesbeuanus was used, a lot of literature on Rana catesbeiana prior to this name change would be lost. Hence, Hillis and Wilcox (2005)[55] proposed Lithobates as a subgenus, whereby it is used in a different sense for smaller group of species. Although notable organizations such as the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), Encyclopedia of Life (EOL) and Animals and Plants of Singapore (APS, LKCNHM) use either Lithobates catesbeianus or Rana catesbeiana. The Centre for Agricultural and Biosciences International [56] (CABI) also advised to use Lithobates as a subgenus and this frog's name could be expressed as Rana (Lithobates) catesbeiana. This would thus maintain and preserve the long historical build up of information on phylogeny and taxonomy of Rana (Lithobates) catesbeiana.Type information

George Shaw (1802) is an English naturalist who gave this bullfrog its original name Rana catesbeiana[57] . He gave the type locality (R. catesbeiana) as “North America”, although that was later restricted to “vicinity of South Carolina”, Charleston by Schmidt (1953). A type specimen is not known to exist. The collector and date of collection are unknown [58] .*Present holotype locality status: Unknown

Original description

Specimen illustrated by Shaw, 1802, Gen. Zool., 3(1): 106, pl. 33 (Permission pending, University of Michigan Library Administration)

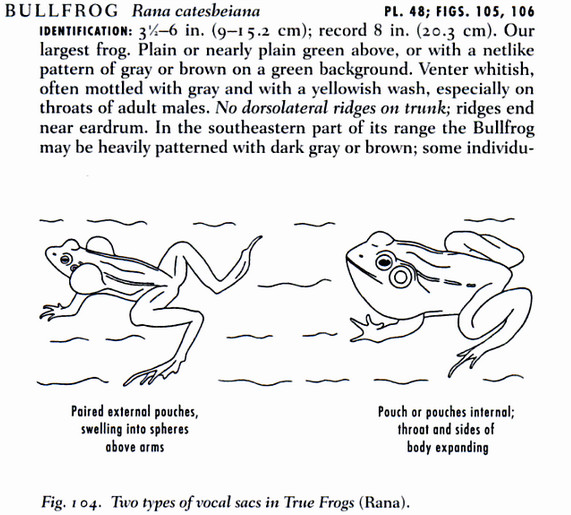

Size very large (maximum SVL 203mm in females). Dorsum green to almost black, or with net-like pattern of gray or brown on green ground; venter whitish, mottled gray (at times), and with a yellowish wash, especially on the throat of males; no dorso-lateral ridges; feet with tip of fourth toe extending beyond web; digital disks absent [59] .

More recent illustrations [60]

(Permission pending, University of Michigan Library Administration)

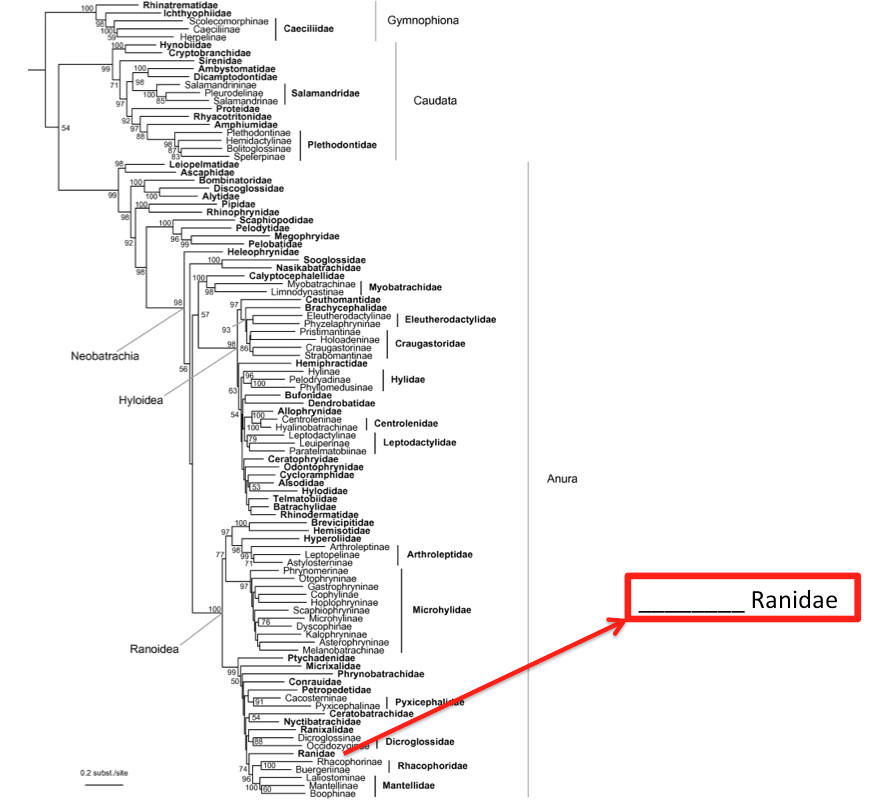

Phylogenetics

A phylogenetic study of Amphibia by Pyron and Weins (2011) has conducted a maximum likelihood analysis on Amphibia phylogeny based on 12,871 base-pairs of sequence data from the concatenation of 12 genes (9 nuclear, 3 mitochondrial), covering both higher and lower taxonomic levels [61] (up to 2800 amphibian species).9 nuclear genes :

- C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR4)

- Histone 3a (H3A)

- Sodium–calcium exchanger (NCX1)

- Pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC)

- Recombination-activating gene 1 (RAG1)

- Rhodopsin (RHOD)

- Seventh-in-absentia (SIA)

- Solute-carrier family 8 (SLC8A3)

- Tyrosinase (TYR)

- Cytochrome b (cyt-b)

- Mitochondrial ribosomal subunit 16S

- Mitochondrial ribosomal subunit 12S

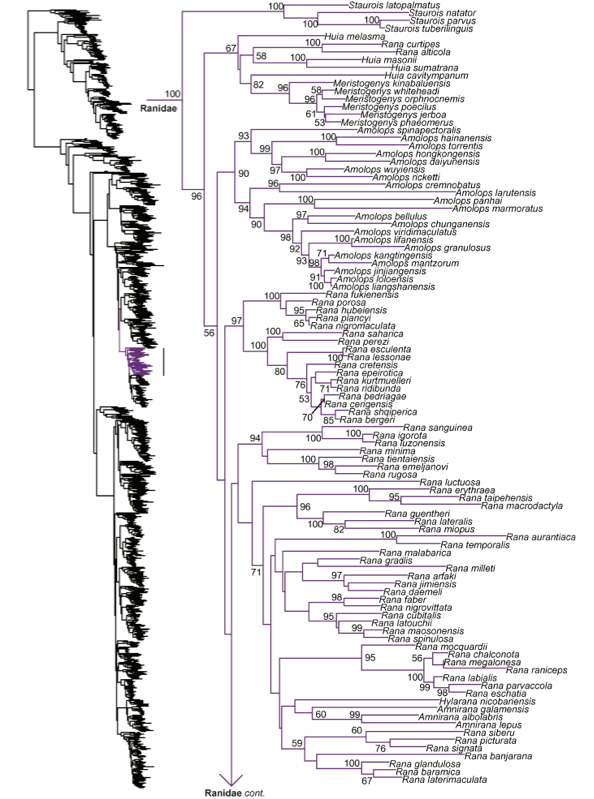

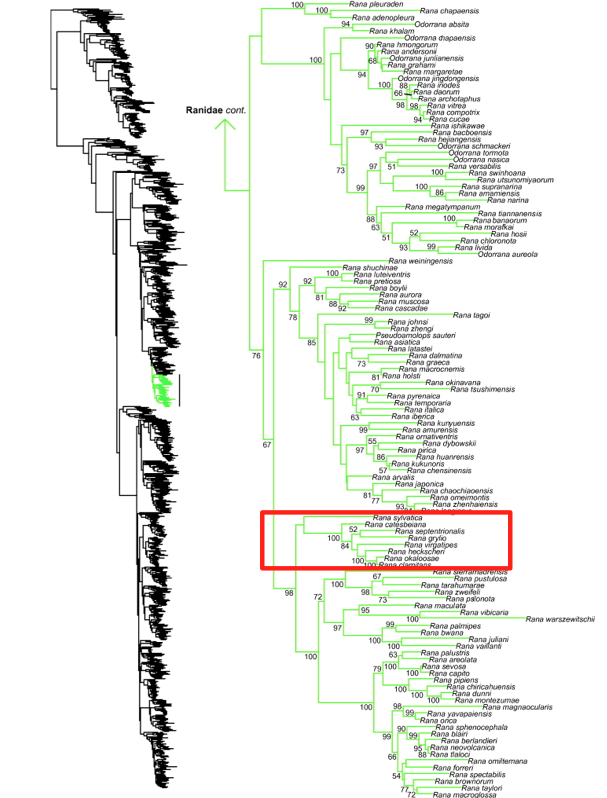

Bootstrap values for maximum likelihood have been indicated on the tree branching nodes for all 3 figures below. (Adapted from Science Direct; direct permission not obtained, but within limits of Fair Use)

Figure 1. Skeletal representation of the maximum likelihood analysis of the concatenated 12 genes of the Orders, Superfamilies and Families in the Class Amphibia.

Moving down the taxonomic hierarchy, the right vertical lines denote the 3 Orders, while the node bases denote the superfamily and line tips represent family. Rana catesbeiana is in the Order Anura, Superfamily Ranoidea and Family Ranidae as boxed in red. Bootstrap values are indicated at the branch nodes.

Figure 2. Family Ranidae phylogeny's maximum likelihood estimate based on concatenated sequencing data of 12 genes (expanded from [Fig. 1])

Rana catesbeiana (American bullfrog) isolated in red is seen to be in the same clade as 7 other Ranoid frog species [62] [63] . This includes the 3 closely related true frogs (annotated with red arrows) namely the R. clamitans (Green frog), R. grylio (Pig frog) and R. heckscheri (River frog), which share the same native geographical range and often mis-identified as R. catesbeiana by para-taxonomists[64] . Bootstrap values are indicated at the branch nodes.

*Compare misidentified Ranoid true frogs

Gene sequences

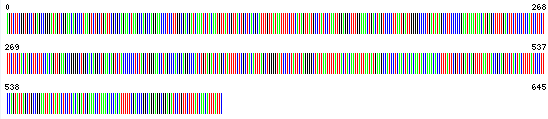

The study by Pyron and Wiens (2011)[65] did not utilize the mainstream barcoding genes like mitochondrial gene (COI) or nuclear gene (18s rDNA) for taxonomic delineation.However, most barcoding data for species delineation published on GenBank commonly involves COI or 18S rDNA. Hence, the following mainstream barcode data has been provided to serve as a linking platform to the respective databases for researchers working on barcoding projects (e.g. eDNA water testing studies that involve Rana (Lithobates) catesbeiana.

The illustrative barcode represents a fragment of DNA sequences, with each base uniquely colored for a rough visual identification of the nucleotide composition makeup of the gene.

| Nucleotide |

Color Code |

| Adenine (A) |

Green |

| Thymine (T) |

Red |

| Guanine (G) |

Black |

| Cytosine (C) |

Blue |

Illustrative COI barcode (646bp) for Rana catesbeiana obtained from BOLD systems that was deposited in NCBI GenBank. COI sequence file (.fasta) can be obtained from GenBank.

Illustrative 18S rDNA barcode (581bp) for Rana catesbeiana obtained from BOLD systems.

18S sequences can be obtained from BOLD systems.

*Back to top

References

- ^ Conant, R., & Collins, J. T. (1975). A Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North. America. Houghton Mifflin, Boston.

- ^ Deutsch, J. & Murakhver, N. (2012). //They Eat That?: A Cultural Encyclopedia of Weird and Exotic Food from Around the World//. ABC-CLIO. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-313-38058-7.

- ^ Daszak, P., Strieby, A., Cunningham, A. A., Longcore, J. E., Brown, C. C., & Porter, D. (2004). Experimental evidence that the bullfrog (Rana catesbeiana) is a potential carrier of chytridiomycosis, an emerging fungal disease of amphibians. Herpetological Journal, 14(4), 201-207.

- ^ Garner, T. W., Perkins, M. W., Govindarajulu, P., Seglie, D., Walker, S., Cunningham, A. A., & Fisher, M. C. (2006). The emerging amphibian pathogen Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis globally infects introduced populations of the North American bullfrog, Rana catesbeiana. Biology letters, 2(3), 455-459.

- ^ WildSingapore, (2006). American Bull Frog Rana catesbeiana. Wildlife Singapore. Accessed on 11 November 2015 (http://www.wildsingapore.per.sg/discovery/factsheet/frogamerican.htm)

- ^

Shaw, G. 1802. General Zoology or Systematic Natural History. Volume III, Part 1. Amphibia. London: Thomas Davison.

Howard, R. D. (1981). Sexual dimorphism in bullfrogs. Ecology, 303-310.

Conant, R., & Collins, J. T. (1975). A Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North. America. Houghton Mifflin, Boston.

Conant, R., & Collins, J. T. (1975). A Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North. America. Houghton Mifflin, Boston.

FAO, (2005). Rana catesbeiana (Shaw, 1802). Cultured aquatic species information programme. Rome, Italy: FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Department, unpaginated. http://www.fao.org/fishery/culturedspecies/Rana_catesbeiana/en

Conant, R., & Collins, J. T. (1975). A Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North. America. Houghton Mifflin, Boston.

Emlen, S. T. (1976). Lek organization and mating strategies in the bullfrog. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 1(3), 283-313.

Boatright-Horowitz, S. L., Horowitz, S. S., & Simmons, A. M. (2000). Patterns of vocal interactions in a bullfrog (Rana catesbeiana) chorus: preferential responding to far neighbors. Ethology, 106(8), 701-712.

FAO, (2005). Rana catesbeiana (Shaw, 1802). Cultured aquatic species information programme. Rome, Italy: FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Department, unpaginated. http://www.fao.org/fishery/culturedspecies/Rana_catesbeiana/en

Emlen, S. T. (1976). Lek organization and mating strategies in the bullfrog. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 1(3), 283-313.

Bury, R. B., & Whelan, J. A. (1984). Ecology and management of the bullfrog. Smith VII.

- Costa, C. L. S., Lima, S. L., Andrade, D. R., & Agostinho, C. Â. (1998b). Morphological characterization of the stages of development of the female reproductive tract in bullfrogs (Rana catesbeiana) reared using an intensive amphibian farming system. Revista Brasileira de Zootecnia, 27(4), 642-650.>

WildSingapore, (2006). American Bull Frog Rana catesbeiana. Wildlife Singapore. Accessed on 11 November 2015 (http://www.wildsingapore.per.sg/discovery/factsheet/frogamerican.htm)

Frost, D. R., Grant, T., Faivovich, J., Bain, R. H., Haas, A., Haddad, C. F., ... & Wheeler, W. C. (2006). The amphibian tree of life. Bulletin of the American Museum of natural History, 1-291.

Shaw, G. 1802. General Zoology or Systematic Natural History. Volume III, Part 1. Amphibia. London: Thomas Davison.

Shaw, G. 1802. General Zoology or Systematic Natural History. Volume III, Part 1. Amphibia. London: Thomas Davison.

Conant, R. (1958). A field guide to reptiles and amphibians of the United States and Canada east of the 100th meridian. Smith II.

Pyron, R. A., & Wiens, J. J. (2011). A large-scale phylogeny of Amphibia including over 2800 species, and a revised classification of extant frogs, salamanders, and caecilians. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 61(2), 543-583

Pyron, R. A., & Wiens, J. J. (2011). A large-scale phylogeny of Amphibia including over 2800 species, and a revised classification of extant frogs, salamanders, and caecilians. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 61(2), 543-583