Sousa chinensis (Osbeck, 1765)Indo-Pacific Humpback DolphinChinese White Dolphin

|

| Taken from underwaterworld singapore. [Permission pending] |

|

| Copyright Ken Fung; Hong Kong Dolphinwatch. |

How many species?

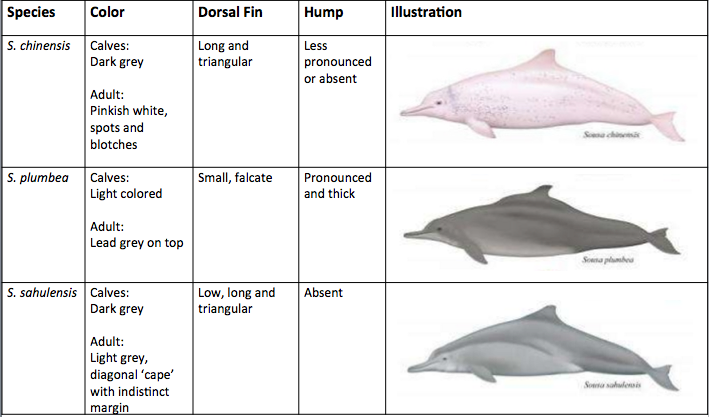

The taxonomy of humpback dolphins genus Sousa has been unresolved for a long time as there appears to be several species. Recent work have shown strong evidence from skeletal morphology, external morphology, molecular genetics and biogeography for 4 species of Sousa[1] .

Generally, there are two types of humpback dolphins recognised according to region, the Atlantic humpback dolphin endemic to the west coast of Africa, and the Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin of the coastal Indian Ocean and western Pacific Ocean. The Atlantic humpback dolphin have been known to consist of one species, Sousa teuszii, while the highly variable Indo-Pacific Humpback Dolphins is being debated. Originally, the Indian humpback and Pacific humpback was considered to be of one species called the Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin, Sousa chinensis. In 2014, the Autralian humpback dolphin, Sousa sahulensis was confirmed to be of a different species from the rest of the Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins[1] [2] .

The remaining Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins are still being debated but many biologists now strongly believe that they consist of two species, the Indian humpback, Sousa plumbea along the Indian Ocean coast, and the Indo-Pacific humpback, Sousa chinensis that is found in eastern India to central China and throughout Southeast Asia*[2][3] .

.

*In this webpage, the dolphin names used will be based on this categorisation. Readers should take note that general information from other websites and papers before August 2014 groups Sousa sahulensis, Sousa plumbea and Sousa chinensis as one highly variable and widespread species: Sousa chinensis (Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin).

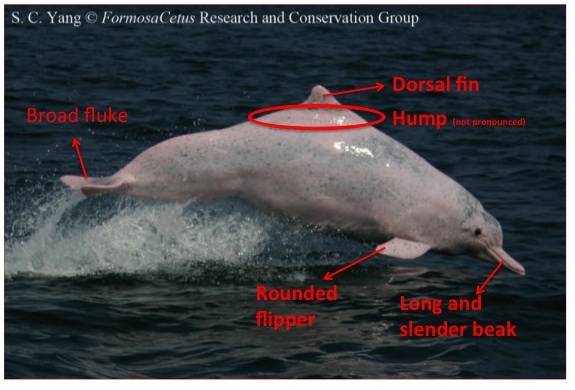

What do they look like?

|

| Simple diagram of the S. chinensis' features. Adapted from Dungan, Riehl, Wee & Wang, 2011 (Permission pending). |

Diagnostic traitsof Sousa chinensis [4][5][6]

- Dorsal fin

- Hump on midback

- Medium sized

- Robust body

- Long and slender beak

- Broad flippers (rounded at the tip)

- Broad flukes

- Maximum length: 2.8m

Maximum weight: 280kg

- Color pattern

- Form of dorsal fin

- Presence of hump

Illustrations obtained with permission from Dr. Thomas Jefferson

|

| Illustration of adult dolphin on top and calf (bottom) found in Singapore. Photo permission pending from TMSI. |

The humpback dolphins around Singapore are part of the S. chinensis species and they are pink.

When born, they are dark grey in colour and look very like a bottlenose dolphin but as they mature their colour changes and the hump on the back becomes more prominent. The dorsal fin triangular and positioned in the centre of the back. They grow to about 2.5-2.8m long and can weigh up to 260kg [9] .

There appears to be no sexual dimorphism in body length and shape for this species but it is speculated for the other species that the males might be larger than the females[1].

Their behaviour?

The behavior of Sousa chinensis is not well-studied but there are a few studies done on certain aspects of the humpback dolphin's behavior.

Movement

Sousa chinensis moves slowly and surfaces at a regular interval[10] . The long beak of the humpback dolphins are often exposed when they surfaces and they strongly arch their back and raise their tail flukes while diving. This is a unique diving posture whereby the dolphin first lift its beak out of the water and arch its back, then pausing before dipping below the surface and flipping its tail to dive[9]. Humpback dolphins also have a characteristic rolling manner of surfacing described by Karczmarski et al (1997) [11] , often with their beak hitting the water before the melon reaches the surface of the water. The rest of the body remains submerged when the blowhole is open[12] .

Indo-pacific humpback dolphins surfacing and diving near a boat in Hong kong. Credit: Patty Tse/Carefordolphins.net

Occurrence

Humpback dolphins are shy animals and so they are not often sighted near boats. They occur in tropical coastal waters, preferring areas less than 25 metres deep[9], so they are usually found in areas including open coasts and bays, coastal lagoons, rocky and coral reefs, mangrove swamps and estuarine areas. It is rare to find them more than a few kilometres from shore[2].

They travel in small sizes of school, usually in three to eight animals, and have been sighted to be in singles or pairs[9]. Parsons (2004) noticed that the occurrence of the dolphins was affected by the tide cycle, with sighting frequency increasing during the ebb tide[12].

|

| Rare Pink dolphins in Hongkong. Photo permission pending from Hong kong University. |

Social behavior

Saayman & Tayler (1973) described some social behaviors exhibited by humpback dolphins in Plettenberg Bay, including leaping, airborne cartwheels, chasing,rubbing against and mouthing each other, and striking each other with their flukes.These social behaviors were often observed when groups and individuals first came together. In Hong Kong, there seems to be a seasonal variation in the occurrence of social interactions between the humpback dolphins, with frequency of social behavior increasing between August and November (Parsons, 1998b). This increase in social behavior also was noted by Jefferson (2000)[12].

Another study done by Karczmarski, Thornton & Cockroft (1997) observed courtship initiation with some vigorous movement of two individuals side by side with consistent, helical interchanging of positions. The dolphins exposed half of their body above the water and displayed prolonged body contact. Aerial displays such as quasi-leaps, side leaps and vertical leaps were also observed. Such behvaior was repeated before the dolphins apparently initiated true mating[11].

Vocalisation

Very little is known about the acoustic repertoire of the Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin. As of now, it is unknown whether the different species of humpback dolphins produce different sounds. Delphinid sounds generally consists of clicks,often used for echolocation, burst-pulses that is generally used for communication, and whistles which are believed to be be used for communication. [13]

A study done by Parijs and Corkeron (2001)[14] off eastern Australia, supported by a study done by Sims et al [13], documented five types of vocalisation produced by humpback dolphins:

- Broad band clicks (also known as "click trains")

- High in frequency (8 kHz to >22 kHz)

- Occurred as a series of clicks

- Frequent during foraging and sometimes in social behavior

- Barks

- Variable frequency (0.6kHz to >22 kHz)

- Burst pulse sound

- Frequent during foraging and social behavior

- Quak

- Variable frequency (slightly lower and shorter duration than Barks')

- Broad band, burst pulse sound with harmonic structure

- Predominant in social behavior and sometimes foraging

- Grunts

- Low frequency (0.9 kHz to 1.4 kHz), short duration

- Occurred as a series of clicks

- Only recorded in social behavior

- Whistle (Type 1 & 2)

- Middle frequency (6.7 kHz to 10.5 kHz)

- Narrow band, frequency modulated sound

- Type 1 and 2 predominant, during milling and traveling

Australian Humpback dolphin swimming near a diver, producing a sound. (Video credits: Jasmine Tan & Clarissa Tan)

Reproduction

Little is known about the reproduction of humpback dolphins as well. Generally, gestation period is approximately 10-12 months and there appears to be a calving peak from spring to summer. Calves are about 100cm long and 14kg at birth[6]. Scant data indicate that sexual maturity in females may occur at about 9-10 years of age, with males maturing later[15] .

What do they eat?

The humpback dolphins appear to be opportunistic feeders, consuming a wide variety fishes. Sometimes they feed on cephalopods, while crustaceans are rare in their diet[2][9]. Feeding primarily occurs near shore, estuaries and reefs[10].

.

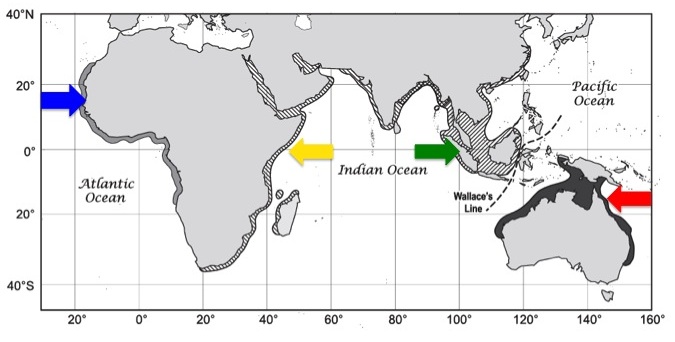

Where are they found?

Sousa chinensis is distributed in waters from central China, south throughout the waters of Southeast Asia as far southeast at least as Borneo, and as far west as the Orissa coast of India. Its distribution overlaps with that of Sousa plumbea. Range states include the People’s Republic of China (including the SARs of Hong Kong and Macau), Taiwan (Republic of China), Vietnam, Cambodia, Thailand, Myanmar, Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, and Brunei Darussalam. Indo-pacific humpbackdolphins typically has a near shore distribution throughout its range[2] [1][9]

|

| Ranges of the different species of Sousa: S. teuszii (light shading indicated with blue arrow), S.plumbea (135 hatching indicated with yellow arrow), S. chinensis (45 hatching indicated with green arrow), and Sousa sahulensis sp. nov. (dark shading indicated with red arrow).Gaps are based on a lack of records, but not all waters of eastern Indonesia have been extensively surveyed for cetaceans. Map adapted from [1] with permission from Dr. Thomas Jefferson. |

Conservation

Under IUCN, the humpback dolphins in the Pacific Ocean and Indian Ocean as a whole is classified under “Near Threatened” and is listed in Appendix I of CITES. These classifications are based on the combination of the humpback dolphins in the Indian Ocean, Pacific Ocean and Australia, consisting of more than 10,000 individuals. Despite the huge total number, these dolphins are under substantial threat[2]. The situation is especially critical for the population of Sousa chinensis in Hong kong and Taiwan. For the eastern Taiwan trait subpopulation, they are classified under critically endangered under IUCN[16] .

An alarming decline of the population in Hong kong was reported from 158 dolphins in 2003 to just 61 dolphins in 2012[17] [18] [19] .

Major threats

- Bycatch

The dolphins live in close proximity to the shore, so they often get caught in fish nets. This results in drowning of the dolphins as they are unable to reach the water surface to breathe. Entanglements of humpback dolphins in gill nets have been recorded in coastal waters of the Indian Ocean[10]. Thousands of trammel and gill nets operate in the coastal waters of western Taiwan and this clearly represents one of the most serious threats to this subpopulation[20] . Shark nets in Australia meant for the protection of swimmers have also killed a substantial number of dolphins[21] .

- Habitat destruction

One of the main driving force due to land reclamation creating disturbance and destroying the dolphins’ habitat.

Since the mid-90s, more than 1,400 hectares of sea area have been reclaimed in Hong Kong’s western waters. This is within the relatively small area inhabited by the dolphins[22] . The construction of the Hongkong-Zhuhai-Macau bridge in recent years runs straight through the dolphins' habitat and the Hongkong government continue to have future coastal development plans.[17]. In addition to a direct loss of the dolphin’s habitats, reclamation has affected fishery resources, which subsequently leads to a decrease in food supply for the dolphins[22]. In China, there are continuing proposals for large-scale industrial development projects involving land reclamation such as offshore wind farms, steel factory of the Formosa Plastic Group, Chinese Petroleum Company’s petrochemical factory within the animals’ restricted habitat[16]. These threats are likely to continue in future with increasing impact as habitat degradation and loss increases with growing human population requirements.

- Vessel collision

Living in congested waters with busy marine traffic, it is not surprising to find the dolphins being hit and injured by ferries and propellers. Many cities also provide dolphin watching tour, further increasing the boat traffic in the dolphins' habitat. There have been an increasing sighting of scars and marks on the dolphins living in Hong kong waters. More recently, a mother dolphin was seen carrying her dead calf who have been cut by a boat propeller[19]. Apart from physical injuries, boat traffic can also affect the acoustic behavior and communication with one another[23] .

- PollutionHong Kong discharges over 2 billion litres of sewage into the waters daily. Parsons (1997) estimated that a humpback dolphin’s minimum daily intake of sewage bacteria through ingestion of contaminated seawater could be up to 70,500 faecal coliforms. In comparison, a one-off ingestion rate of 200-300 coliforms is considered unacceptable for humans[22].Industrial, agricultural and residential discharge poses a risk to the dolphins via the consumption of marine prey species. Spills of oil and other toxic substances by commercial ships could be catastrophic for a population so small and limited in its distribution especially the Eastern Taiwan Strait subpopulation[16][24] .

Documentary: The Perilous Recovery of The Taiwanese White Dolphin. Permission granted by Vancouver Aquarium.

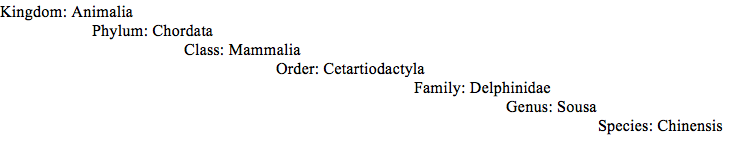

Taxonomy

Scientific Name[25]

- Scientific: Sousa chinensis (Osbeck, 1765)

- Vernacular: Indo-Pacific Humpback Dolphin, Chinese white Dolphin, Pink dolphin

- Synonym:

Delphinus chinensis, Osbeck 1765 (Basionym)

Delphinus sinensis, Desmarest 1822 (Synonym)

Sotalia plumbeus, Flower 1883 (Synonym) Sotalia sinensis, Flower 1883 (Synonym)

Steno (Sousa) lentiginosus, Gray 1866 (Synonym)

Steno chinensis, Gray 1871 (Synonym)

Sotalia chinensis, True 1889 (Synonym)

Steno lentiginosus, Blanford 1891 (Synonym)

Sotalia borneensis, Lydekker 1901 (Synonym)

Sousa lengtiginosa, Iredale &Troughton 1934 (Synonym)

Stenopontistes zambezicus, Miranda Ribiero 1936 (Synonym)

Sousa borneensis, Fraser & purves 1960 (Synonym)

Sousa queenslandensis, Gaskin 1972 (Synonym)

Sousa huangi, Wang 1999 (Synonym)

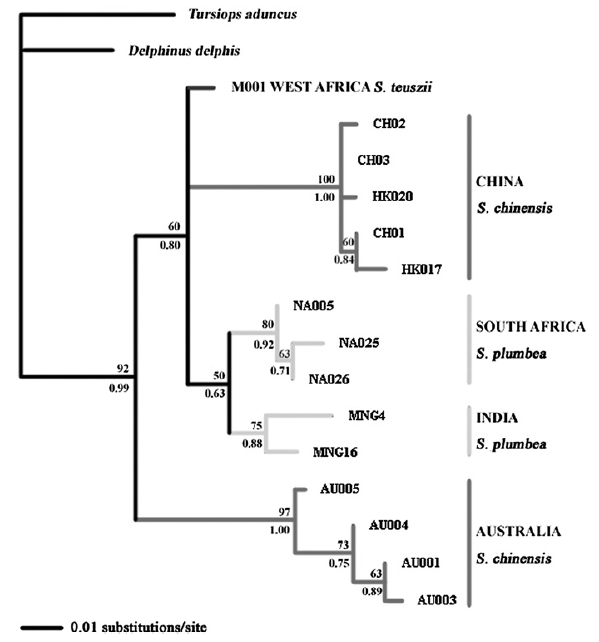

Maximum likelihood (ML) reconstruction of relationships among Sousa spp. based on mtDNA control region haplotypes (287-bp) from five regions: China

(Xiamen, Hong Kong and other regions), South Africa (Natal), Australia (Queensland and other regions), India, and West Africa (Mauritania). ML bootstrap scores

are shown above internal nodes and Bayesian posterior probability scores are shown below. ML and Bayesian methods converged on the same tree. Terminal

nodes are labeled with haplotype codes as in Table 2. Sequences from Delphinus delphis and Tursiops aduncus were used as outgroups.

Reproduced from Stewart, Clapham & Powell, 2002.

Type information

The first binomial, Delphinus chinensis, was given to the Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin when it was first observed in the Canton (Pearl) River, China and described by Pehr Osbeck (Swedish explorer) in 1757. The species name, chinensis, refers to the original location of the animals observed by Osbeck[20].

No type specimen was collected[20]. This description was one year before Linnaeus' taxonomic system was published in 1758, thus by the Law of Priority, Osbeck's (1765) German translation must be used for taxonomic purposes as the original description. Flower (1870) provided a type and a detailed description of the skeleton of Sousa chinensis, thereby solving the problem of the lack of a holotype specimen. However, the holotype specimen was later destroyed in World War II [26]. A neotype from Hong Kong was later proposed (Porter 1998), but the specimen was a subadult[27] .

German translation of the original swedish description of Sousa chinensis by Osbeck. Photo permission pending.

German translation of the original swedish description of Sousa chinensis by Osbeck. Photo permission pending.Jefferson, T. A., & Rosenbaum, H. C. (2014). Taxonomic revision of the humpback dolphins (Sousa spp.), and description of a new species from Australia. Marine Mammal Science, 30(4), 1494-1541.

Boesak, T., 2015. Interesting facts about Humpback dolphins (Sousa sp.). Ocean Blue Adventures. Accessed on 20 November 2015.

http://oceanadventures.co.za/interesting-facts-humpback-dolphins-sousa-sp/

Stewart, B. S., Clapham, P. J., & Powell, J. A. (2002). Guide to marine mammals of the world. AA Knopf.

http://www.cms.int/reports/small_cetaceans/data/S_chinensis/s_chinensis.htm

State of Queensland, 2015. Australian humpback dolphin. Queensland government, Department of Environment and Heritage Protection. Accessed on 20 November 2015. https://www.ehp.qld.gov.au/wildlife/animals-az/indopacific_humpback_dolphin.html

http://seamap.env.duke.edu/species/180419

TMSI, 2011. Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin (Sousa Chinensis). Tropical Marine Science Institute, NUS. Accessed on 10 November 2015.

http://www.tmsi.nus.edu.sg/mmrl/sousa.htm

Perrin, W. F., & Wursig, B. (Eds.). (2009). Encyclopedia of marine mammals. Academic Press.

Karczmarski, L., Thornton, M., & Cockroft, V. (1997). Description of selected behaviours of humpback dolphins, Sousa chinensis. Aquatic Mammals, 23, 127-134.

Sims, P. Q., Vaughn, R., Hung, S. K., & Würsig, B. (2012). Sounds of Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins (Sousa chinensis) in west Hong Kong: a preliminary description. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 131(1), EL48-EL53.

Van Parijs, S. M., & Corkeron, P. J. (2001). Vocalizations and behaviour of Pacific humpback dolphins Sousa chinensis. Ethology, 107(8), 701-716.

Jefferson, T. A., & Hung, S. K. (2004). A review of the status of the Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin (Sousa chinensis) in Chinese waters. Aquatic Mammals,30(1), 149-158.

Reeves, R.R., Dalebout, M.L., Jefferson, T.A., Karczmarski, L., Laidre, K., O’Corry-Crowe, G., Rojas-Bracho, L., Secchi, E.R., Slooten, E., Smith, B.D., Wang, J.Y. & Zhou, K. 2008. Sousa chinensis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2008: e.T20424A9197694. . Downloaded on 10 November 2015

http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/133710/0

CNN, July 19, 2013. China’s white dolphins headed for extinction in Pearl River delta? Cable News Network, International edition. Accessed on 23 November 2015.

http://edition.cnn.com/2013/07/19/world/china-hong-kong-white-dolphin-extinction/

- >

Perrin, W. and Vanden Berghe, E, 2009. Sousa Chinensis (Osbeck 1765). World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS). Accessed on 8 November 2015.

http://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=220226