Brown-banded Cockroach

Brown-banded Cockroach

Table of Contents

|

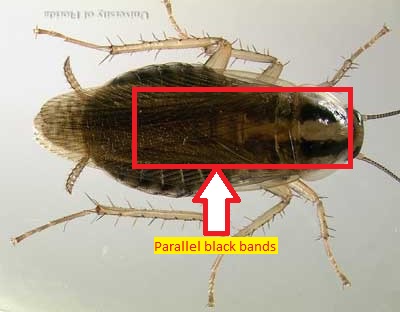

| Fig. 1: The brown-banded cockroach is a household pest that can be found in Singapore. Image courtesy of Arab Pest Control. |

The brown-banded cockroach is a domiciliary cockroach that can be found in Singapore. Unlike the two other more common species that can be seen scurrying around our neighborhoods, which are the American cockroach and the German Cockroach, this one tend to hide in buildings and are less often seen in public. These three have been regarded as pests in countries that they are found in, hiding in human residence and other urban buildings. Most people do not know the difference between the three species of cockroaches that plague us, generalising all cockroaches to be of the same 'icky' status. Of the three, the brown-banded cockroach is the least known as it is the most elusive species, yet it is the most likely of the three to hide in our houses! Read on to find out more about this nasty little critter and how is it different (especially the methods that should be employed to rid of them!) from the other two species!

Note: If you have Katsaridaphobia, or the fear of cockroaches, and would like to skip the photos as they will give you insufferable nightmares, click here to skip to the pest control methods!

1. Description

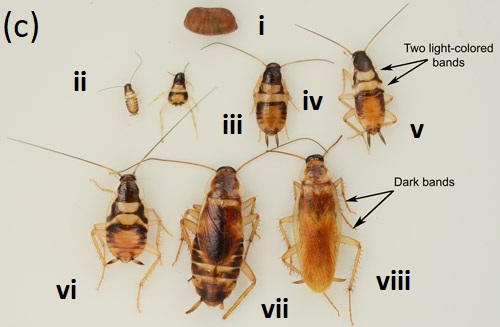

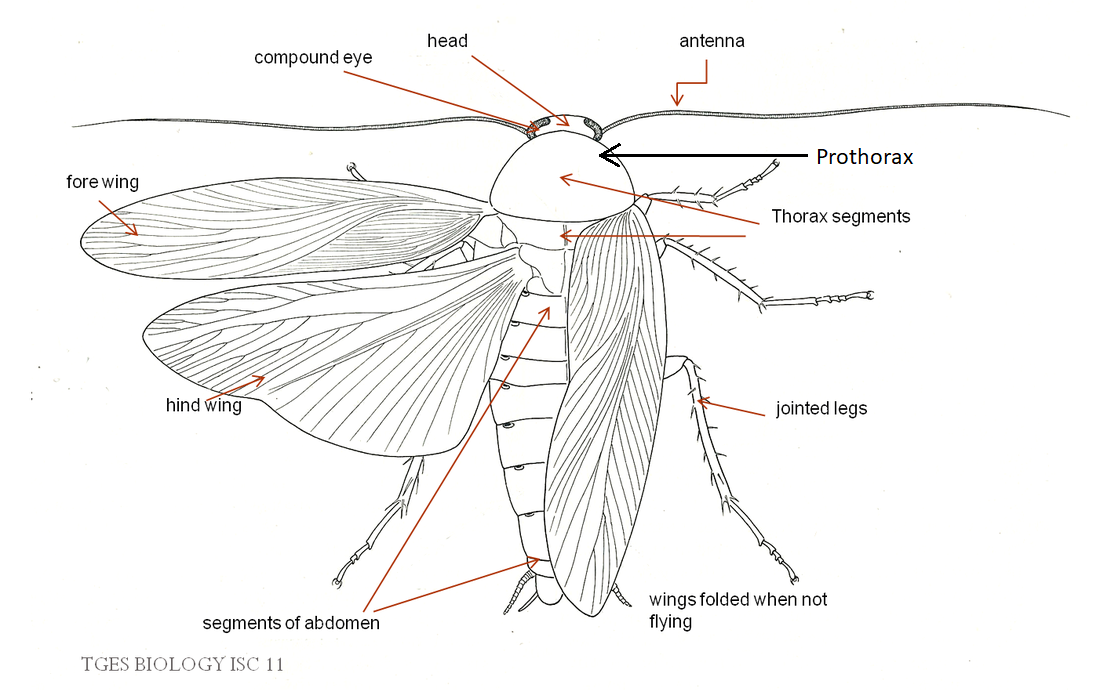

The brown-banded cockroach has an oval and vertically flattened body shape[19]. This is an evolutionary trait which has been attributed their ancestors who thrived in loose soil, and this body shape allows them to burrow easily[21]. |

|

|

|

| Fig. 2: a) Close-up of a male brown-banded cockroach. The distinguishing dark band is not as obvious as a result of the lighting, refer to cviii for a clearer photo of the dark band below the pronotum. b) Close-up of a female brown-banded cockroach. The banding patterns on the abdomen are more prominent. For comparison, refer to cvii) (female) and cviii) (male). c) Different life stages of the brown banded cockroach. (i) An egg case (ootheca) laid by a female. (ii - vi) Different time period of a nymph. Notice the two, prominent light-coloured bands present on the abdomen, below the pronotum. (vii) A fully-developed female brown-banded cockroach. (viii) A fully-developed male brown-banded cockroach. Photographs a) and b) modified, and courtesy of James L. Castner, University of Florida. Photograph c) modified, and courtesy of Lyle J. Buss, University of Florida[24]. |

|

|

| Fig. 3: A sketch of a cockroach (general morphology, may vary across species). The pronotum is an obvious disc-like structure that covers the thorax or a part of it[27]. The pronotum of a brown-banded cockroach covers the prothorax area, and the distinctive band marks appear below the pronotum. Sketch courtesy of Gajendra Khandelwal and Deepthi Uthaman[26]. |

2. Ecology and Behavior

2.1 Distribution

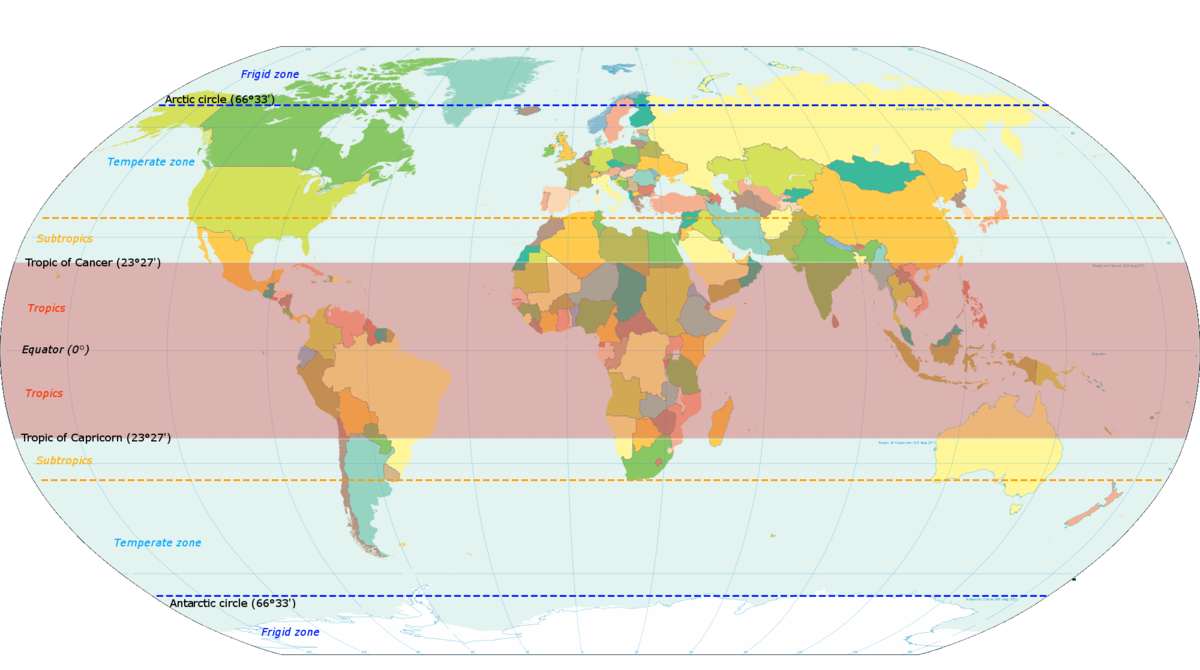

The brown-banded cockroach originated from Africa, but they can now be found almost everywhere in the world[11][24]. This was attributed to modern transport, and further expedited with the invention of ships and planes[23]. The tiny pests can hide themselves in the nooks and crannies until they reach their destination, and establish a hated community there. |

| Fig. 4: World map, showing the tropical (shaded in red) and the subtropics (region between dotted-yellow line and red area). The brown-banded cockroach was listed as a circumtropical species[2], but there are records of them appearing in temperate regions, albeit more scattered in urban regions and in smaller population sizes[1][20][24]. Goes to show that we are not the only ones who have to tolerate its presence. Image obtained from Wiki user KVDP. |

Cockroaches are known for being extremely hardy, capable of surviving harsh temperatures or prolonged duration of shortage of food[29]. For the brown-banded cockroach, it has a more specific temperature range. Compared to other species of cockroaches, the brown-banded cockroach prefers areas which are warmer, hence they are usually found near motors, near heated components of refrigerators, and in temperate countries, near room heaters[1][24][25][30].

Note: Cockroaches are known to be so hardy that even tested with radiation levels that were multiple times more than the lethal dose to humans, they can survive! Does this mean that cockroaches will be able to withstand a nuclear apocalypse??? Check out the experiment here!

2.2 "Batman"?

|

| Fig. 5: A cockroach cartoon superimposed on Batman. (Source: Author) |

Male brown-banded cockroaches can exhibit flight behavior, and it was suspected that they do so either when they are foraging or when they are threatened; females are incapable of flight[1][24], which could be attributed to their disproportionately small wings.

2.3 Pest!

Cockroaches, including the brown-banded cockroach, are known to harbour pathogens (anything that causes diseases) which can cause various conditions in humans[24]. Diseases such as gastroenteritis and dysentry are caused by the pathogens, leading to ailments such as incomplete defecation, fever, abdominal pain, lack of energy, diarrhoea, dehydration. A common type of food poisoning known as Salmonella, is also caused by the pathogens that are left on exposed food when cockroaches have visited them for a snack[25].More specifically, the brown-banded cockroach is one that prefers starchy food. In homes, if they do not have exposed rice or noodles, their feeding trail can be seen in books, newspapers, or anything else that has been coated with glue or paste. Even non-food materials such as clothes are known to have attracted them, likely due to the presence of residual body oil or skin flakes (YUCKS!)[30].

3. Other Enemies of Mankind

Most people in Singapore are not fond of cockroaches, because they have been associated with unsanitary and unclean places. They are known to carry with them bacteria that cause illnesses to humans[17]. Many people think that just by having a clean environment, there will be lesser chance of housing cockroaches in their residences. However, different cockroaches have different methods of prevention[1]. To effectively prevent infestation of the brown-banded cockroach, we have to first be able to distinguish them between the other common species that can be found and understand the difference in their behavior. As adults are more often seen than the nymphs, identification keys on pest control websites usually list the difference of adult characteristics.Including the brown-banded cockroach, there are two other recognised cockroaches which are seen scurrying around Singapore and considered pests. They are the American Cockroach (Periplaneta americana (Linnaeus, 1758)) and the German Cockroach (Blattella germanica (Linnaeus, 1767))[2].

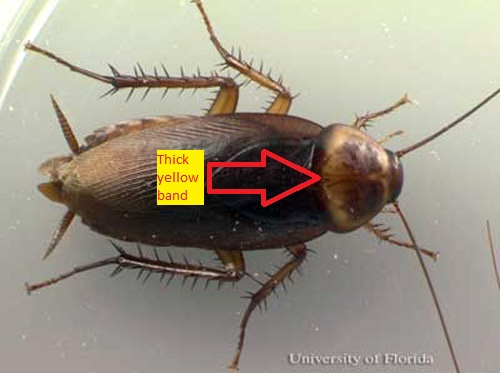

| Fig. 6: A close-up photo of a male American cockroach, the largest species of cockroach pest found in public places and households. Photograph courtesy of P. G. Koehler, University of Florida[22]. |

Fig. 7: A close-up photo of another common pest, a male German cockroach. They are known to be more commonly found among food waste. Image courtesy of P. G. Koehler, University of Florida[23]. |

3.1 American Cockroach

The largest and most commonly seen species of cockroach dominating rubbish chutes and sewers is the American cockroach, and they flocks in areas which are unsanitary and unclean. The most obvious feature to identify this 'bugger' is a thick, horizontal yellow or pale-brown band found at the base of its pronotum (Fig. 6), which can be found in adult females as well (Fig. 8). Adults grow to about 4 cm, with the females being slightly smaller (Fig. 8). This is because the wings of males extend beyond their abdomen, making it appear longer and bigger. This species is also easily identified by its size, as adults grow up to be twice as big as the German cockroach or the brown-banded cockroach[22]. They have a reddish-brown to dark-brown abdomen, and are the ones that people see most often. Often when you hear someone scream as a result of a persistently flying cockroach, it is likely that this species is the one causing mischief. Studies done on this species have found that they can carry AT LEAST 22 types of bacteria which can cause illness to humans due to their preference for human waste and dirty environment[22]! |

|

| Fig. 8: A photograph of a female American cockroach. If allowed a closer look, it can be seen that the wings do not extend beyond the abdomen, unlike the males, and that they have a more brownish tinge for the band on the pronotum. Photograph courtesy of P. G. Koehler, University of Florida[22]. |

Fig. 9: A photograph of a female German cockroach. Females are distinguished from the males with their different body contour, as females tend to have a shorter and more stout abdomen. Their wings also extend past their bodies, unlike the males, where the wings just about cover their abdomen. Photograph courtesy of P. G. Koehler, University of Florida[23]. |

3.2 German Cockroach

The next most common species of cockroach which can be seen occasionally is the German cockroach. This species of cockroach is similar in size to the brown-banded cockroach, but the preferred living conditions of the two species differ. The German cockroach is most easily identified with the dual, parallel black band running down the pronotum from its eyes (Fig. 7), also observed on the females (Fig. 9). Despite possessing fully-developed wings that cover the abdomen, the German cockroach is not capable of flight[19]. This might be the case, but they are known to be able to flutter their wings for very low propelled flight, which could potentially result in screaming people as well. This species of cockroach are almost always found only in areas with human presence[19]. Interestingly, this species is more attracted to food waste than the American cockroach or brown-banded cockroach, and it is known to cause bite marks on people's faces if food matter can be found on it[23]. This is no wonder our parents always encourage us to clean our faces after meals.4. Pest Control Methods

Fight or flight, this is the basal instinct of almost every living thing. This can be observed in a person's response to a cockroach (or any pest). They will either scream or run away from it (flight response) or they will choose the more noble task of attempting to kill it (fight). Physically flattening them with an object has proven to be ineffective to them, as they have the ability to survive up to 900 times their own weight!

Warning: This video is not for the faint-hearted (yes, that's you if you cannot survive the images above).

Many insecticides and pesticides have been developed to effectively exterminate the bane of our existence. However, constant use of insecticide may result in cockroaches gaining immunity[20]. Hence, to effectively eliminate purely domiciliary pests, an integrated approach have to be applied, which consists of multiple measures that complements with chemical measures. This is known as Intergrated Pest Management (IPM)[24].

A paper published by Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (IFAS) in United States mentioned that the IPM is the most effective way to deal with indoor pests, and that there are two stages to pest management: 1. prevention and sanitation, and 2. elimination[24].

| Category |

How and why is it effective? |

| Exclusion |

Measures should be taken to prevent cockroaches from even entering a household.

By preventing them from even entering a household, this reduces the odds of an infestation even happening! |

| Elimination of Water Source |

Cockroaches tend to find areas which have water sources readily available. However, in the case of a tropical climate, they have discovered that this might not be the case for cockroaches. Water retention within the arthropods are higher due to the higher humidity and relatively constant or high rainfall. As such, for Singapore, this might not be the most effective method in preventing cockroach infestations. Nevertheless, still water should be cleared as they could cause an outbreak of another plague, the Dengue fever. Fun fact: cockroaches can only survive without up to 42 days without food, but without accessible water sources, they can only survive up to 12 days[28]. |

| Elimination of Food Source |

Without food, they may be weakened, but they are able to wait out days of food shortage for as long as 42 days (that's more than a month). Readily available food sources allows them to proliferate rapidly, and we would not want this would we? In an article shared by Rentokil Initial, they mentioned that starchy food or any starchy material such as glue, are the brown-banded cockroaches' favorite food source. As such, remember to clean up your mess at home after meals to prevent cockroaches from being attracted to your house! Waste bins should be cleared regularly as well. Note: In high-rise buildings, a rubbish chute which can be found at every level can potentially be a nest for these vermin, hence they should be checked and ensure they are sealed properly as well! |

| Elimination of Harbourage |

In addition to having food and water, just like us, cockroaches seek shelter as well! The brown-banded cockroach is known for roosting in areas which are warmer (which, in Singapore's tropical weather, is almost anywhere) and dark in the day. Here are some methods provided by Rentokil Initial to prevent any form of potential spots for cockroaches to seek refuge:

|

| Table 1: List of Prevention and Sanitation methods that are compiled by IFAS and Rentokil to prevent an infestation of cockroaches[28]. |

|

Note: Chemical measures should be used out of reach from children and pets, as they contain harmful chemicals! Do check the proper use of these tools as you would not want to waste your money on them!

5. Etymology (How the cockroach got its name!)

The first actual description of the species was named by Johan (Christian) Fabricus in 1798, under the name Blatta longipalpa[7]. Jean Guillaume Audinet-Serville described Blatta supellectilium in 1838 from Blatte des meubles (French for furniture cockroach, because he was French) as it was commonly found amidst furniture[11]. Also, the species name supellectilium originated from the Latin noun "supellex" which meant household items. However, the species was often reported as Supella supellectilium[8].The name supellectilium grew in popularity after 1900 as the species established itself more in numerous countries, and older records of this species were recorded as Supella supellectilium[7]. The specimen collected by Dr. Karlis Princis in 1960 and by Ella Zimsen in 1964 were both consistent with the specimen kept in Fabrician Collection, where the original specimen was obtained in Kiel, Germany[8][12]. However, as both the behavior and description of Blatta supellectilium and Blatta longipalpa were described very similarly, it affirmed that the species described by Serville was the same one described by Fabricus. After a review of Princis' and Rehn's record from 1947 and 1963 respectively, the species name longipalpa was retained by priority. This was done in 1970, where Ashley B. Gurney perused old records of cockroach descriptions and decided to conventionalize the name Supella longipalpa[7].

6. Taxonomy

Presently, the brown-banded cockroach are listed under the following rankings[2][31]:Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Arthropoda

Class: Insecta

Order: Blattodea

Suborder: Blattaria

Superfamily: Blaberoidea

Family: Blatellidae

Subfamily: Pseudophyllodromiinae

Genus: Supella

Species: S. longipalpa

There are 4,600 species of cockroaches identified to date and they are all under the order Blattodea, further supported with recent advancements in phylogenetic studies[2][10]. However, inter-species relationship within the order are still under debate, including the relatedness of S. longipalpa with other species.

The placement of cockroaches in the tree-of-life has been widely debated and volatile ever since Linnaeus described the genus Blatta in 1758 (only nine species were described back then)[3]. Since then, different systems have been utilized, resulting in the ever-changing classification of cockroaches.

The first morphological and anatomical system of classification employed for cockroaches was the McKittrick's System (1964)[4][17][18]. She used four main characteristics: Female reproductive organ; Male reproductive organ; proventriculus; and oviposition behaviour. She recognized that her system was insufficient in proving the relationship between species, but classifications in the higher taxa (family level and higher) were largely conserved when more characteristics were considered[5], even with the advent of molecular phylogeny[6]. Presently, studies attempting to resolve the phylogeny of Dictyoptera relied mainly on the asymmetry of male genitalia[13][15][17].

6.1 Phylogenetics

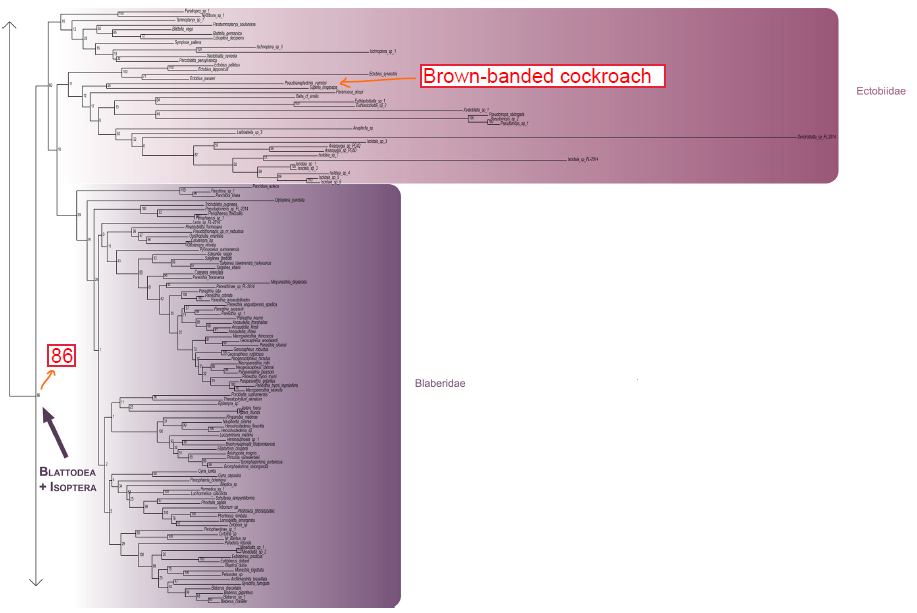

Supella longipalpa was initially under the order Orthoptera, which included grasshoppers, locusts and crickets[5]. The order was renamed Blattariae by Princis in 1960 by reviewing the work of earlier taxonomists[8]. The names Blattaria and Blattariae were used interchangeably with the implementation of McKittrick's System in 1964, but Blattariae became defunct as the "-ae" ending was standardized for insect families and subfamilies[7]. The order Dictyoptera with the suborder Blattodea was then proposed by Kevan in 1977, but because the classifications he proposed seemed troublesome and included other lesser known ranks, such as cohort and subcohorts, it was not widely accepted[9]. Grandcolas' proposal in 1996 had very similar structure to that of Mckittrick's System in 1964, with the exception of some family level distance relationships[3][5]. It was finally classified within the order Blattodea[16].The relationship between cockroaches and termites has also been debated widely among scientists. In the past, they were classified under the order Blattodea[8][9][11], and many debated if termites should actually belong to the same order or have their own separate order. It was only from recent studies that sufficient evidence proved that termites are actually eusocial cockroaches, hence the termites actually belong to the same order as cockroaches (Fig. 10)[10][13][14]!

|

| Fig. 10: Results from a concatenation analysis, showing the support of relationship (bootstrap values = BS) within the order Blattodea. The boxed out value (BS = 86). Image obtained and modified from Legendre et al.[10]. |

6.2 Future studies

More studies have to be conducted to confidently determine the position of S. longipalpa and other species of cockroaches within the order. Some suggestions brought up to improve the accuracy of phylogenetic studies on them were:1. Wider variety of representatives (species) to represent the ingroups and outgroups[13][14]

2. Use of nucleic data (nDNA) over mitochondrial DNA (mDNA), as mDNA are more heterogeneous with respect to among-site variations, and nDNA can define closely related species more clearly[15]

3. Use of morphological studies to complement molecular studies as no one study can distinguish between species completely[10]

7. Literature Cited:

- Department of Agriculture (1996) Chapter Six: Insect and Insect-like Pests. In: Integrated Pest Management in Montana Schools Training, A Study Manual for IPM in Montana School Pest Applicators. Issued by Department of Agriculture, Montana, Helena. Pp. 27

- Beccaloni G.W. (2017). CockroachSF: Cockroach Species File (version 5.0, Jun 2017). In: Roskov Y., Abucay L., Orrell T., Nicolson D., Bailly N., Kirk P.M., Bourgoin T., DeWalt R.E., Decock W., De Wever A., Nieukerken E. van, Zarucchi J., Penev L., eds. (2017). Species 2000 & ITIS Catalogue of Life, 30th October 2017. Digital resource at www.catalogueoflife.org/col. Species 2000: Naturalis, Leiden, the Netherlands. ISSN 2405-8858.

- Louis M. Roth (2003) Systematics and Phylogeny of Cockroaches (Dictyoptera: Blattaria). In: Oriental Insects. Published by Taylor & Francis Online. Volume 37, Issue 1.

- Mckittrick F. A. (1964) Evolutionary Studies of Cockroaches.

- Moore J. & Gotelli N. J. (1996) Evolutionary Patterns of Altered Behavior and Susceptibility of Parasitized Hosts. In: Evolution, Volume 50, Issue 2. Pp. 807-819

- Kambhampati S. (1995) A Phylogeny of Cockroaches and Related Insects Based on DNA Sequence of Mitochondrial Ribosomal RNA Genes. in: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Volume 92, No. 6. Pp. 2017-2020

- Ashley B. Gurney (1970) On the Scientific Name of the Brown-Banded Cockroach Supella longipalpa (Fabricus) (Dictyoptera, Blattaria, Blattellidae). In: Cooperative plant pest report (Volume 20, No. 27). Issued by U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Administration, Bureau of Entomology and Plant Quarantine, in Washington D.C. Pp. 752 - 754

- Princis K. (1960) Zur Systematik der Blatterien. In: Eos 36, No. 4.

- Kevan, D. K. McE. (1977) The higher classification of the orthopteroid insects: A general view. In: XV International Congress of Entomology. Pp. 1-31.

- Legendre F., Nel A., Svenson G. J., Robillard T., Pellens R., & Grandcolas P. (2015) Phylogeny of Dictyoptera: dating the origin of cockroaches, praying mantises and termites with molecular data and controlled fossil evidence. PLoS One, Volume 10, Issue 7.

- Audinet-Serville, J. G. (1839). Histoire naturelle des insectes: Orthoptères (Vol. 1). Roret. Pp. 114.

- Zimsen, E (1964) The type material of I. C. Fabricius. Copenhagen. Pp. 656.

- Wang, Z., Shi, Y., Qiu, Z., Che, Y., & Lo, N. (2017). Reconstructing the phylogeny of Blattodea: robust support for interfamilial relationships and major clades. Scientific Reports, 7(1).

- Ware, J., Litman, J., Klass, K., & Spearman, L. (2008). Relationships among the major lineages of Dictyoptera: the effect of outgroup selection on dictyopteran tree topology. Systematic Entomology, 33(3), 429-450.

- Che, Y., Gui, S., Lo, N., Ritchie, A., & Wang, Z. (2017). Species Delimitation and Phylogenetic Relationships in Ectobiid Cockroaches (Dictyoptera, Blattodea) from China. PLOS ONE, 12(1), e0169006.

- Vélez A. (2008). Checklist of Colombian cockroaches (Dictyoptera: Blattaria). Biota Colombiana, 9(1), 21-37.

- Klass, K. D., & Meier, R. (2006). A phylogenetic analysis of Dictyoptera (Insecta) based on morphological characters. Entomologische Abhandlungen, 63(1-2), 3-50.

- Grimaldi, D., & Engel, M. S. (2005). Evolution of the Insects. Cambridge University Press.

- Rust, M. K., Owens, J. M., & Reierson, D. A. (Eds.). (1995). Understanding and controlling the German cockroach. Oxford University Press on Demand.

- Schal, C., Gautier, J. Y., & Bell, W. J. (1984). Behavioural ecology of cockroaches. Biological Reviews, 59(2), 209-254.

- Gorochov, A. V. (2001). On the higher classification of the Polyneoptera. Acta Geologica Leopoldensia, 24, 11-56.

- Valles, S. (1996). German cockroach - Blattella germanica (Linnaeus). Entnemdept.ufl.edu. Retrieved 15 November 2017, from http://entnemdept.ufl.edu/creatures/urban/roaches/german.htm

- Barbara, K. (2000). American cockroach - Periplaneta americana (Linnaeus). Entnemdept.ufl.edu. Retrieved 15 November 2017, from http://entnemdept.ufl.edu/creatures/urban/roaches/american_cockroach.htm

- Jiang, S., & Lucky, A. (2016). brown-banded cockroach - Supella longipalpa. Entnemdept.ufl.edu. Retrieved 15 November 2017, from http://entnemdept.ufl.edu/creatures/URBAN/roaches/brown-banded_cockroach.htm

- Bell, W., Roth, L., Nalepa, C., & Wilson, E. (2007). Cockroaches: Ecology, Behavior and Natural History. JHU Press

- Khandelwal, G., & Uthaman, D. Morphology and anatomy of cockroach. BIOLOGY4ISC. Retrieved 15 November 2017, from http://biology4isc.weebly.com/morphology-and-anatomy-of-cockroach.html

- Pronotum - Entomologists' glossary - Amateur Entomologists' Society (AES). (2017). Amentsoc.org. Retrieved 15 November 2017, from https://www.amentsoc.org/insects/glossary/terms/pronotum

- Koehler, P., Bayer, B., & Branscome, D. (1994). Cockroaches and Their Management. In Pests in and around the Southern Home (4th ed.). Institute of Food and Agricultural Science.

- How to spot and stop a cockroach infestation at home. (2017). Home & Decor Singapore. Retrieved 2 December 2017, from http://www.homeanddecor.com.sg/articles/79835-how-spot-and-stop-cockroach-infestation-home

- Jacobs, S. (2002). Brownbanded Cockroaches. Entomological Notes.

- Retrieved October 23, 2017 from the Integrated Taxonomic Information System on-line database, http://www.itis.gov.