Common Barn Owl

Tyto alba (Scopoli, 1769)Redirected here from this article?

|

| Article on barn owl visiting Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong[1] |

Or because of Harry Potter?

| Scene from Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone by elyusai1 |

Continue reading to find out more about this cute owl!

Table of Contents

|

|

| Photograph of the Common Barn Owl at Grand Union Canal by just1snap under Creative Commons (CC) |

Introduction

Tyto alba, commonly known as the Common Barn Owl, is an almost cosmopolitan species in the family Tytonidae, which is one of the two main lineages of owls - the other being Strigidae (typical owls). Within this family, there are two subfamilies - Tytoninae and Phodilinae (bay owls). Species of this family can be recognised by their distinct rounded head with heart-shaped facial disc and the white to brown plumage[2] . In Singapore, this species is an uncommon breeding resident[3] , identified as the subspecies T. a. javanica[4] .Morphology

Adult

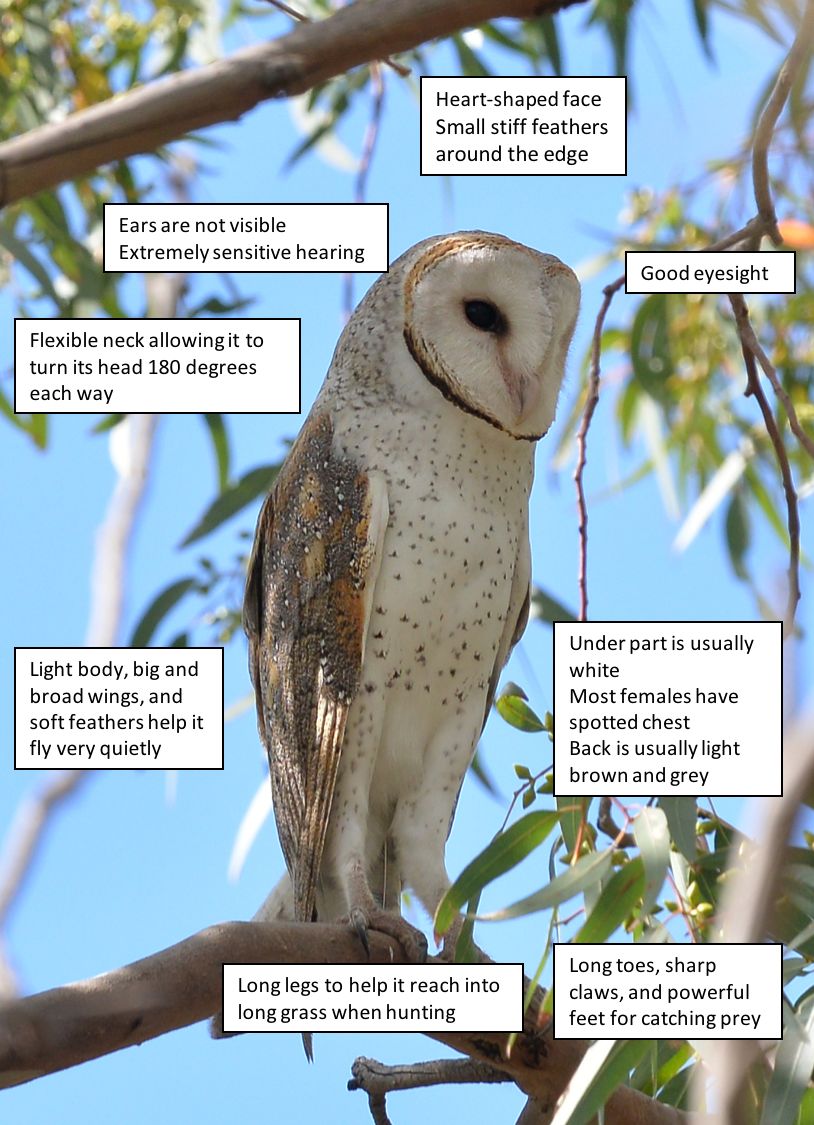

All barn owls are highly distinct by its prominent heart-shape face and lack of ear tufts unlike typical owls (see image below). |

|

| Modified by Neo Shi Hui Theresa with reference[5] Photograph of a barn owl (Family Tytonidae) by Jean and Fred under CC |

Modified by Neo Shi Hui TheresaPhotograph of a typical owl (Family Strigidae) by Peter Roberts under CC |

The common barn owls are medium-sized, measuring 290 - 440mm from head to toes[6] , with slight variations between each subspecies. The Singapore's subspecies, T. a. javanica, ranges from 340 - 360mm[7] . They have very variable body weight amongst subspecies, ranging from 187g (Europe, North Africa) to 700g (North America)[8] . Females are generally larger than males in all aspects except for wing chord and tail length. Female T. alba alba can be differentiated with their male counterparts by their darker colour and presence of flecking under wings[9] . The plumage (feathers) of subspecies is highly variable (see subspecies) - most are white to light brown. The wing feathers of are rounded with 10 primaries, 15 secondaries and 12 rectrices.[10] Other distinct features (from typical owls) include: short, squarish tail (see image below) and relatively small, dark eyes.

|

| Photograph of a barn owl by Patrick Dirlam under CC |

Young

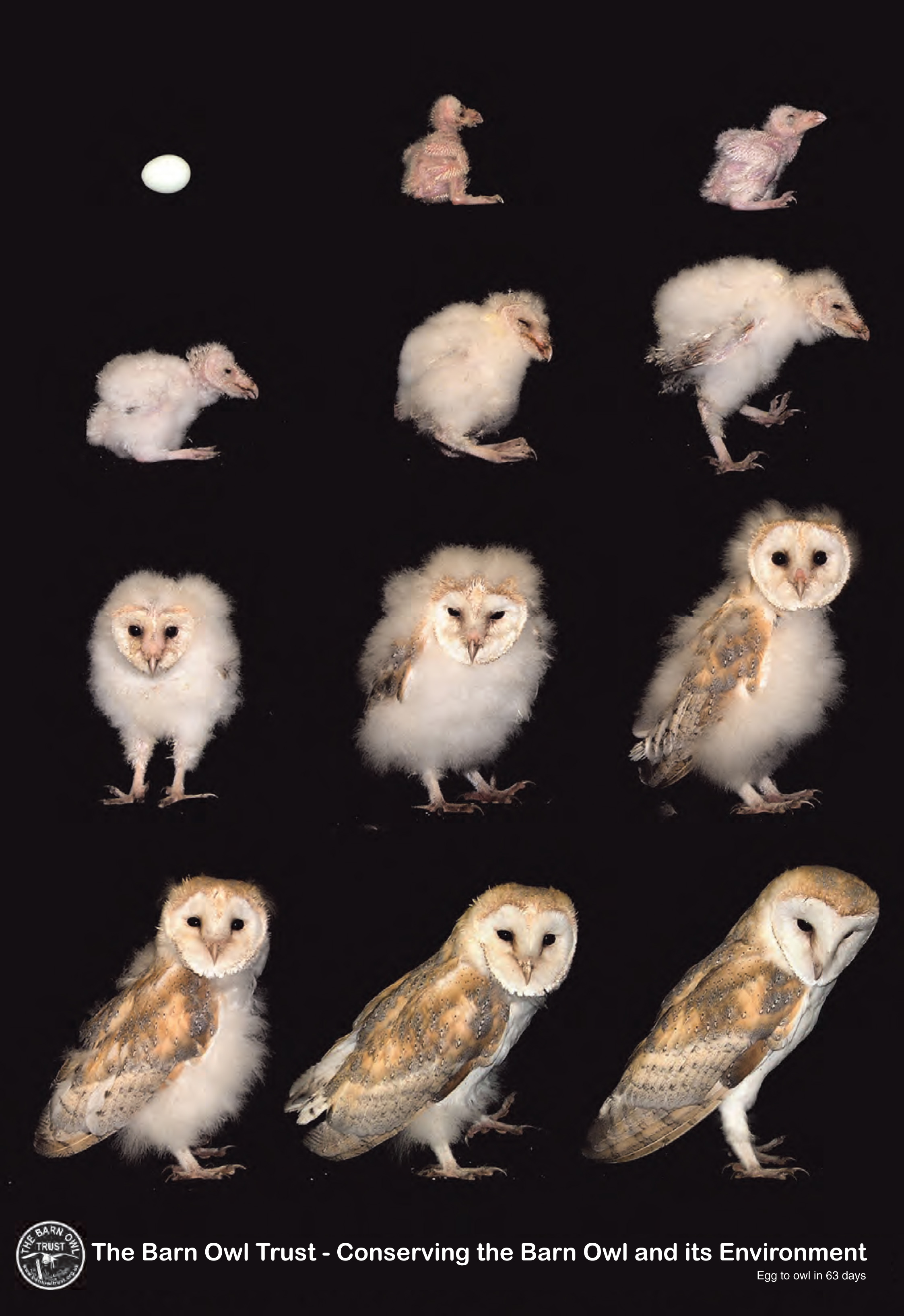

Young are born bare on the neck, belly and back while the other parts of their body have a thin whitish down. The characteristic heart-shaped face is visible after the third week of hatching[11] . The plumage of fledglings is similar to that of adults with more spots and they may molt prior to reaching adult plumage[12] . They will exceed the body mass of adults during growth stage and the weight is lost prior to flight. They have to be taken care by the parents till they are able to support themselves.Check out this link to see more comparison images of the barn owls!

Sound

Unlike most owls that hoot, the male T. alba makes an eerie screeching and hissing sound. They also give a purring call – the males use it to invite a female to inspect the nest whereas the females use it to beg for food from the male[13] . Compared to males, female's call is lower-pitched and more broken[14] .| Recording of male flight call (screeching sound) by Jarek Matusiak under CC |

| Recording of female call by Kelley Nunn under CC |

Distribution and habitat

Global

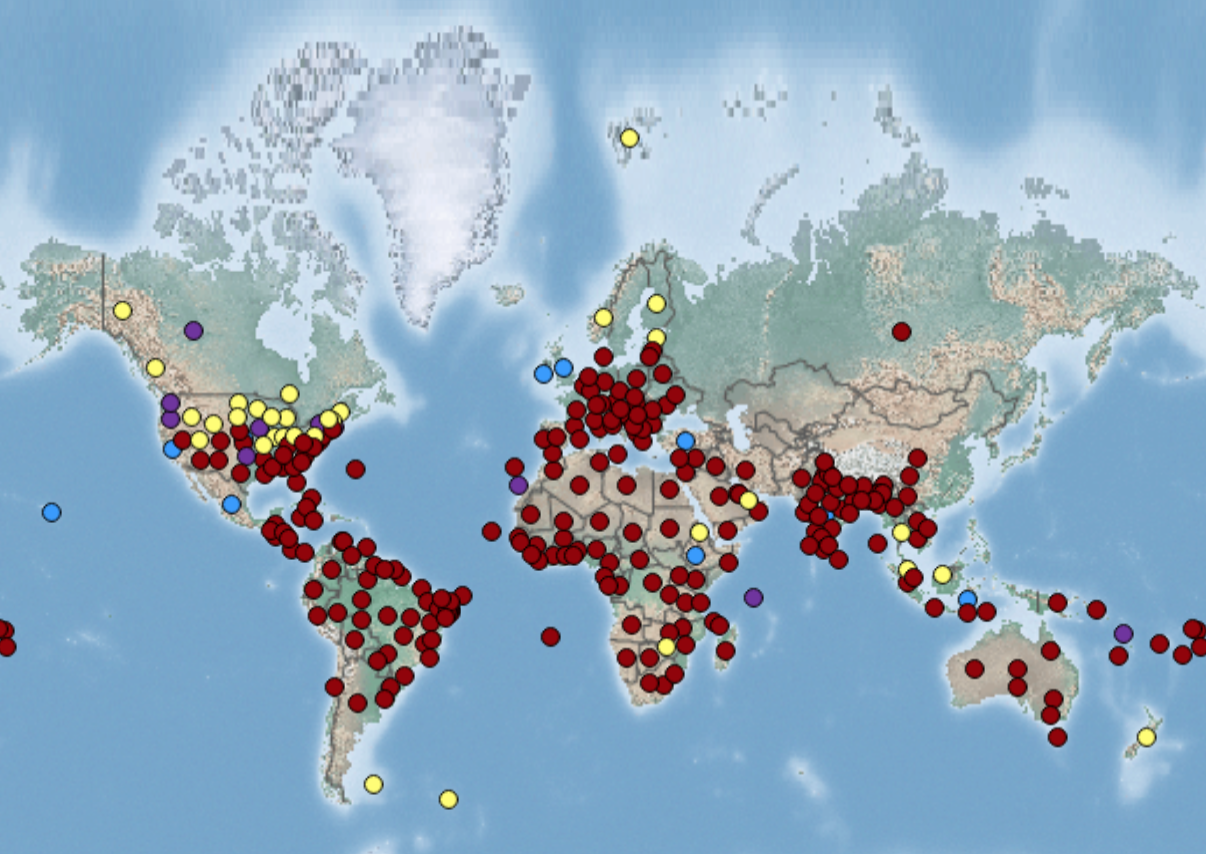

T. alba are found on all continents except for Antarctica. The absence in cold climate is due to an inability to store sufficient energy reserves. They are also not found in the Sahara Desert, heavily forested or mountainous areas[15] . |

| Global distribution of Tyto alba by CABI under CC. Red dots represent present, no further details, yellow dots represent occasional or few reports, blue dots represent widespread and purple represent localised. |

Singapore

In Singapore, T. alba came over from Malaysia as a result of the expansion of oil palm plantations in the 1960s, where they were introduced in control rat problems[18] . The first record of the barn owl on 18 February 1970 when one was struck by a military aircraft[19] . The subspecies found in Singapore is javanica[20] (IOC’s newly revised version listed T. alba javanica now as T. javanica javanica, whereas other sites remain as T. alba javanica). The javanica subspecies originates from the Malay Peninsula[21] . They have been sighted at several locations in Singapore, but mostly found in the eastern and southern side of the island. They are seldom found in tree holes and usually take residence under highways and bridges, in the roof of houses and under man-made structures[22] . A pair in Singapore has been known to nest under the Benjamin Sheares Bridge[23] . Interestingly, a barn owl (could be the same individual) has visited Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong at the Istana three times (2013[24] , 2015[25] , and 2017[26] ).| Locality map of Tyto alba distribution in Singapore created by Neo Shi Hui Theresa with references to sighting reports[27][28][29][30][31][32] |

Ecology and behaviour

|

| A barn owl from egg to adult in 63 days © Barn Owl Trust - Frances Ramsden |

Diet

Barn owl's diet has been extensively studied in Europe, North America, Israel, South Africa, South America and Australia[33] . More than 75% of their diet consist of small mammals, dominated by rats and mice. Other diet includes shrews, gliders, small opossums, lizards, birds. Non-mammalian preys are caught incidentally or opportunistically, but in semi-arid regions and tropics, they can contribute to a significant proportion[34] . They are picky eaters, usually only feeding on few species and when food is scarce, many starve rather than switch to alternatives[35] . They eat their prey whole, which suggests the small size of their preys, but they do not digest the fur and bone. These are then regurgitated in the form of a pellet. Analyzing the pellets would allow scientist to know what exactly the owl had eaten. On average, they eat 4 small mammals daily[36] .Hunting

| Slow motion video of an barn owl attack by BBC Earth Unplugged |

Barn owls have been highly adapted for hunting. Some of their adaptations include[38] :

- Heart-shaped face funnels sound to their ears

- Ear openings are slightly lopsided to allow them to sense how far away the sound is to them

- Long legs allowing them to catch prey in long grasses

- Sharp talon, strong feet to effectively hold onto the small mammals

- Low wing loading - broad wings supporting a light body - allowing them to hover with the slightest lift

- Light feathers for quiet flight

- Extremely light sensitive eyes to locate prey in the dark

- Colour-shading feathers - white underside and brown upperside - for camouflage purposes

|

| Photograph of a barn owl with its prey by Martha de Jong-Lantink under CC |

Nest

Barn owls do not build nest but instead use cavities in trees or man-made nest box for their nest. Individuals can adapt to virtually anything but they prefer to be kept out of sight, sheltered from rain and wind, and feel safe[39] . They lay their eggs on the previous year's nest debris (compacted pellet) or, if there are no debris, stones or wood.Man-made nest boxes (see image below) are encouraged by owl sites to provide a safe site for barn owls to nest.

|

| Photograph of a barn owl in a nest box by Oregon Department of Fish & Wildlife under CC |

Breeding

Barn owls have a unique reproductive strategy which like unlike other raptors (predatory birds) that is more similar to that of the small non predatory songbird: a short but highly productive breeding season[40] . In tropics, breeding can happen any time of the year, but they have a preference of laying eggs late into the dry season. Whereas in arid region, such as Australia and Africa, they prefer to lay eggs during wetter periods. Because of the warm temperatures throughout the year, multiple clutches are often bred. In temperate regions, distinct non-breeding periods emerge, with preference to lay eggs in spring (March-June). The first laying dates are highly variable, often dependent on the weather pattern and prey population cycle. Older females tend to breed earlier so that they may be able to breed two clutches. The clutch size is 4-7 eggs on average and the incubation period is 29-34 days[41] .Lifespan

The global average lifespan of a barn owl is approximately 21 months[42] , with the average lifespan of barn owls in the UK to be 4 years[43] . However, most barn owls die young. The survival rate of fledglings in the first year is 0.370[44] . Low survival rate is due to the difficulty to survive through winter. During winter, these young are especially vulnerable because of their inexperience in hunting which results in starvation. The average fledging success is only 2.5 individuals, with an average of 4 hatching success [45] .Environmental impact

In some countries and states, barn owls were first introduced to control rats in a plantation[46][47] . However, in most locations, they were unsuccessful in controlling the rat populations. Introduction of the barn owl have caused problems to other birds or owls as well[48] . On Mahé Island, Seychelles, a local race of Gygis alba candida, White Tern, was nearly eliminated. The barn owl feeds on Magpie Robins, which competes with the Seychelles Scops owl and Seychelles Kestrel. In Hawaii, the barn owl could be a competitor for the native Short-eared Owl for food and habitat.Conservation status

Tyto alba, as a species, is categorized under 'least concern' by the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species[49] . However, the status of some population, especially those of island taxa, is unclear[50] . In some states of North America, the barn owl is listed as 'endangered at the state level' and 'species of special concern' [51] .Cause of death

In the Northern Hemisphere, the most significant cause of death is likely to be overwinter death as the owls are unable to store sufficient energy reserves and the low prey population[52] . Juveniles are particularly vulnerable because of their unskilled hunting abilities. In other parts of the world, especially places with high traffic, the owls are susceptible to colliding with vehicles because of their close proximity to ground during hunting. In Singapore, our tall buildings poses a threat to these owls and other birds[53] . Occasionally, these owls die from consumption of rat poison that were used to kill rats.Taxonomy

Taxonomic rank

| Kingdom: |

Animalia |

| Phylum: |

Chordata |

| Class: |

Aves |

| Order: |

Strigiformes |

| Family: |

Tytonidae |

| Genus: |

Tyto |

| Species: |

T. alba |

Nomenclature

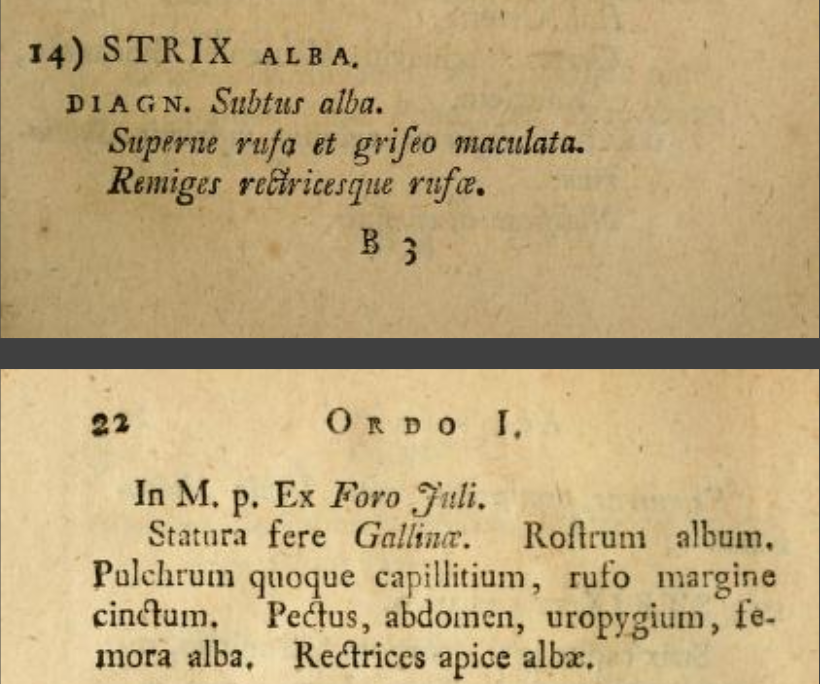

Binomial: Tyto alba (Scopoli, 1769)Synonyms: Strix alba Scopoli, 1769

They are commonly known as the Common Barn Owl, Western Barn Owl (after recent revision following the split of clade (see subspecies)). Other common names which refer to their appearance, call, habitat and flight, include ghost owl, demon owl, and monkeyfaced owl. The chinese name is 仓鸮(cāng xiāo) and malay name is Hantu-Serak Biasa[54] . The name literally means "white owl", from the onomatopeic Greek tuto, which means night owl, and Latin alba, which means white[55] .

Original description

This species was first described by Tyrolean physician and naturalist Giovanni Antonio Scopoli in 1769 in his Annus I-[V] Historico-Naturalis as Strix alba[56]However, the genus Strix, under the typical owl family, Strigidae, came to be used solely for wood owls following more discoveries of owl species. Barn owl is then renamed as Tyto alba, under the barn owl family, Tytonidae.

|

| Original description of common barn owl in the Annus I-[V] Historico-Naturalis[57] Direct translation (by wiktionary): "Above red and grey spotted. Flight feathers reddish. Fruili, Italy Stature resembles chicken. White beak. Beautiful head of hair surrounded by reddish margin. Chest, abdomen, posterior side, thigh white. Rectrices tip white." |

Type specimen

A type specimen can be found in University of California Museum of Paleontology[58] .Phylogeny

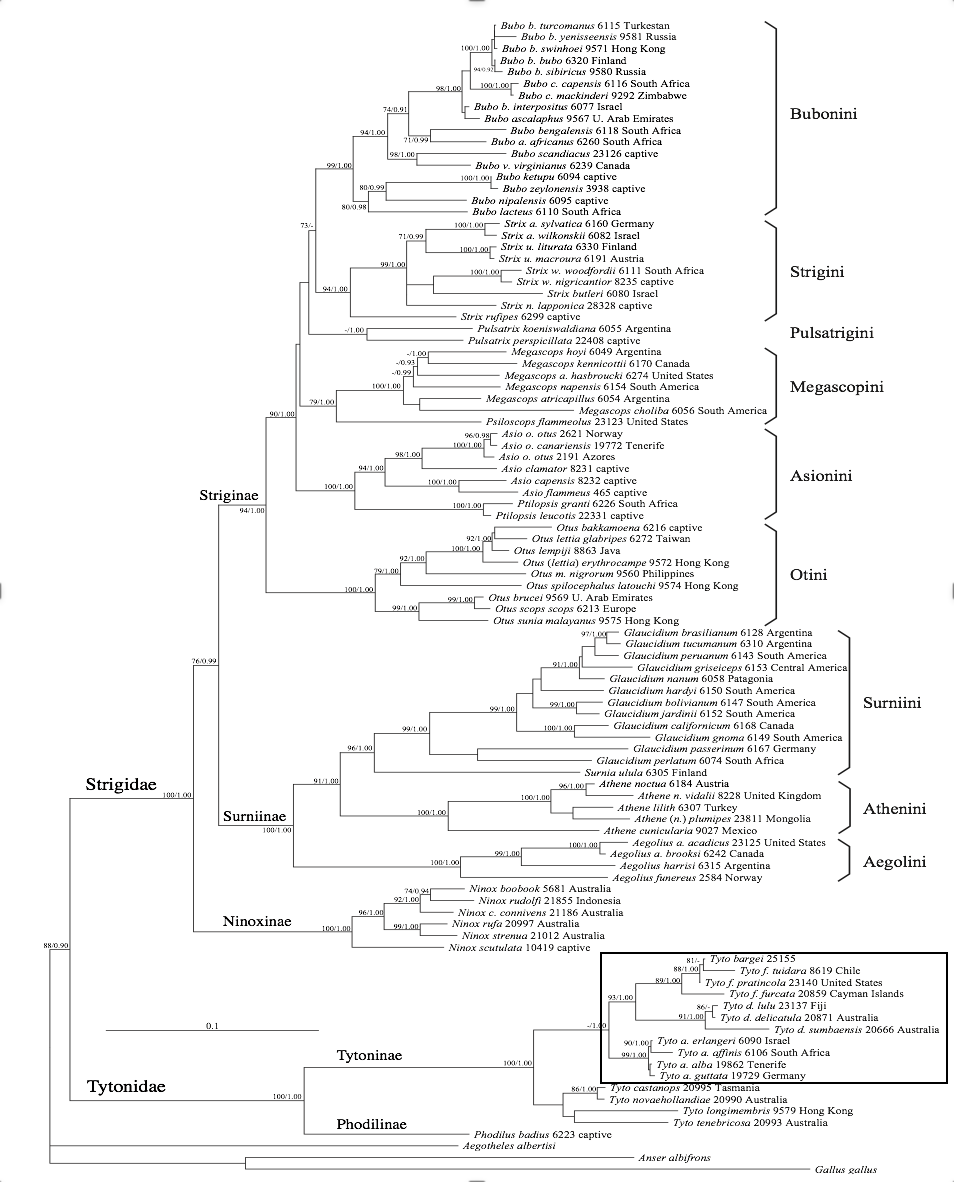

Wink et al. (2009) sequenced the mitochondrial cytochrome b and nuclear RAG-1 gene of 97 owl taxa[59] . |

| Phylogenetic tree of common barn owl based on cytochrome b and RAG-1 gene[60] . Maximum likelihood (ML) bootstrap values/Bayesian inference (BI) posterior probability values indicated for each node. |

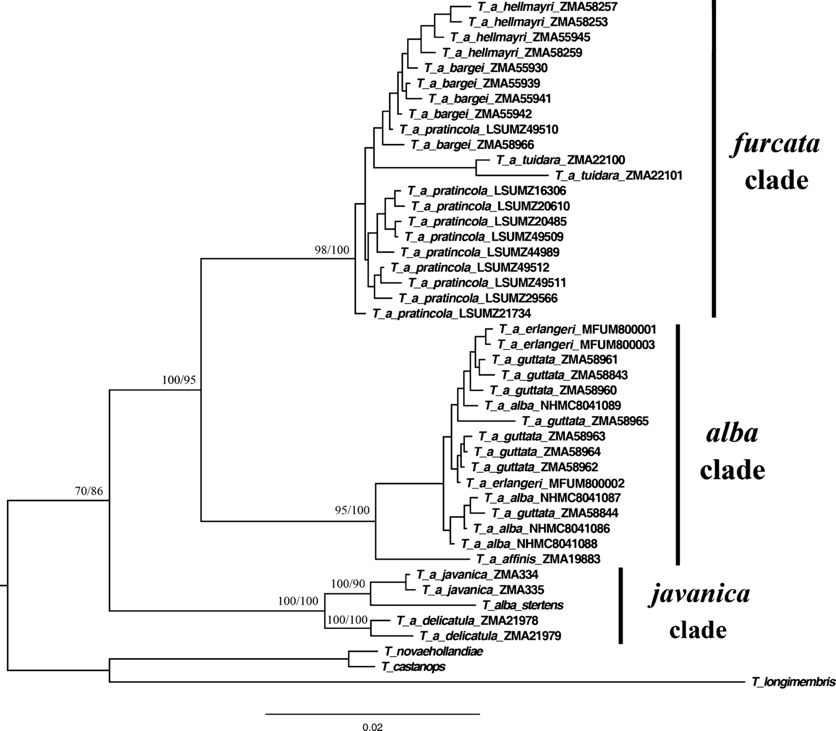

Aliabadian et al. (2016) sequenced the 16s, Cox1, cytochrome b and RAG-1 gene and proposed changes to the taxonomy of the subspecies into three different clades instead of all under T. alba.

|

| 50% majority-rule consensus tree based on 16s, Cox1, cytochrome b, Rag-1 gene[61]. BI posterior probability values/ML bootstrap values indicated for each node. |

Subspecies and race

|

|

| Photograph of the dark breasted barn owl (T. a. guttata) by Tim Ellis under CC |

Photograph of a barn owl (likely T. a. javanica) in Jurong Bird Park, Singapore by _paVan_ under CC |

Several taxonomy changes has been proposed:

- Split of the American barn owls, except bargei, and regarded as distinct species: Tyto furcata[69]

- Split of Tyto alba into three different clades - T.alba (Africa, Europe), T. furcata (New world, including bargei), and T. javanica (Australasia, including delicatula and stertens)[70]

| Subspecies |

Citation |

Locality[72] |

Description[73] |

|

| T. a. alba |

(Scopoli, 1769) |

Northwest Africa, west and south Europe to the Balkans |

Upperside: Grey and light buff. Underside: White with few very small blackish or brown-grey spots on the side of the body. Tail: pale yellowish-brown or pale brownish-yellow with cross bars. |

|

| T. a. guttata |

(C.L. Brehm, 1831) |

Central Europe and east Balkans to the Ukraine |

Upperside: More grey than alba. Underside: Buff to rufous with some dark sports. Face: Whitish. Females are on average redder below than males. |

|

| T. a. ernesti |

(Kleinschmidt, 1901) |

Corsica and Sardinia |

Upperside: Similar to alba. Underside: Breast region is very often pure white without any spots. Tail: White without bars |

|

| T. a. erlangeri |

W.L. Sclater, 1921 |

Crete and Cyprus through the Middle East to south Iran |

Upperside: Lighter and yellower than ernesti. Wings and tail more darkly and broadly banded. Underside: More spots Similar to ernesti |

|

| T. a. schmitzi |

(Hartert, 1900) |

Madeira and Porto Santo Island |

Small Underside: Breast region light buff Similar to guttata |

|

| T. a. gracilirostris |

(Hartert, 1905) |

East Canary Islands |

Small Underside: Breast darker than schmitzi, approaching guttata. Face: Light buff |

|

| T. a. detorta |

Hartert, 1913 |

Cape Verde Islands |

Similar to guttata, but less reddish. Face: Buff |

|

| T. a. poensis |

(Fraser, 1843) |

Africa south of the Sahara, Bioko Island (Gulf of Guinea) |

Upperside: Golden-brown and grey with very bold pattern. Underside: Light buff with extensive speckles. Face: White T. a. affinis merged with poensis (latter has priority) |

|

| T. a. hypermetra |

Grote, 1928 |

Comoro Islands and Madagascar |

Larger and more powerful feet than affinis (now merged with poensis) |

|

| T. a. thomensis |

(Hartlaub, 1852) |

São Tomé Island (Gulf of Guinea) |

Small Upperside: Dark brownish grey with bold pattern, with lighter brown bands on remiges and rectrices. Underside: golden brown with extensive speckles. Face: Buff |

|

| The following are subspecies that Aliabadian et al. (2016) proposed to be treated as separate species[74] . Proposed names are written in the brackets. These names are updated in the latest version of IOC World Bird Names as well. |

||||

| T. a. furcata (Tyto furcata furcata) |

(Temminck, 1828) |

Cuba and Isle of Pines, Cayman Islands and Jamaica |

Significantly larger than pratincola Upperside: Pale orange buff Underside: White with few flank spots |

|

| T. a. pratincola (T. f. pratincola) |

(Bonaparte, 1838) |

South Canada to north Mexico, Bermuda, Bahamas and Hispaniola |

Upperside: Pale orange-buff to lighter or darker grey mixed with orange-buff Underside: White to pale orange, spotted or vermiculated brown |

|

| T. a. guatemalae (T. f. guatemalae) |

(Ridgway, 1874) |

West Guatemala to Panama, Pearl Islands and Colombia |

Darker pratincola (extent of difference undeterminable) Upperside: More uniformly coloured Underside: Coarsely speckled |

|

| T. a. bondi (T. f. bondi) |

Parkes & Phillips, 1978 |

Bay Islands off north Honduras (Roatán and Guanaja) |

Smaller and paler than pratincola |

|

| T. a. hellmayri (T. f. hellmayri) |

Griscom & Greenway, 1937 |

Guianas to north Brazil, Margarita Island, Trinidad and Tobago |

Larger than tuidara Upperside: Dark to pale yellowish above Underside: Near-white to golden-buff below, with or without dusky spotting |

|

| T. a. niveicauda (T. f. niveicauda) |

Parkes & Phillips, 1978 |

Isle of Pines (off Cuba) |

Whiter and paler than furcata |

|

| T. a. contempta (T. f. contempta) |

(Hartert, 1898) |

West Colombia to Venezuela, Ecuador and Peru |

Upperside: Black with fine grey mottling and white spots at feather tips Underside: Pale rusty-brown below with irregular black cross-markings Highly variable plumage within species |

|

| T. a. tuidara (T. f. tuidara) |

(J.E. Gray, 1829) |

Brazil south of the Amazon to Tierra del Fuego and Falkland Islands. |

Upperside: Dark to pale yellowish aboveUnderside: Near-white to golden-buff below, with or without dusky spots |

|

| T. a. bargei (T. f. bargei) |

(Hartert, 1892) |

Curaçao |

Similar to alba but smaller, with shorter wings |

|

| T. a. punctatissima (T. f. punctatissima) |

(Gould & Gray, GR, 1838) |

Galapagos Islands |

Small Upperside: Dull brown with few scattered dusky white spots Underside: Golden-buff to white with brownish vermiculations or fine dense spots |

|

| T. a. stertens (Tyto javanica stertens) |

Hartert, 1929 |

Indian subcontinent to north Sri Lanka, west and east of Pakistan, Assam and Myanmar, east of southern central China (Yunnan), Vietnam and south Thailand |

Upperside: Pale and greyish Underside: Pale with small spots |

|

| T. a. javanica (T. j. javanica) |

(Gmelin, 1788) |

Malay Peninsula to Greater Sundas |

Similar to alba Upperside: More golden-buff Underside: Larger spots |

|

References

- ^ "Barn owl visits Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong again, for the third time in five years" by Lydia Lam. Straits Times, 26 August 2017. URL: http://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/barn-owl-visits-prime-minister-lee-hsien-loong-again-for-the-third-time-in-five-years (accessed on 1 November 2017)

- ^ Bruce M.D. 1999. Family Tytonidae (barn-owls). In J. del Hoyo, A. Elliott, and J. Sargatal (Eds.), Handbook of the Birds of the World. Vol. 5. Barn-Owls to Hummingbirds (pp. 34–75) Barcelona: Lynx Edicions

- ^ "Bird" by National Parks. National Parks, 28 November 2016. URL: https://www.nparks.gov.sg/biodiversity/wildlife-in-singapore/species-list/bird (accessed on 3rd December 2017)

- ^ "Western Barn Owl" by Singapore Birds Project. Singapore Birds Project, n.d. URL: https://singaporebirds.com/species/western-barn-owl/ (accessed on 1 November 2017)

- ^ "Barn Owl facts" by The Barn Owl Trust. The Barn Owl Trust, 2017. URL: https://www.barnowltrust.org.uk/barn-owl-facts/ (accessed on 1 November 2017)

- ^ Bruce M.D. 1999. Family Tytonidae (barn-owls). In J. del Hoyo, A. Elliott, and J. Sargatal (Eds.), Handbook of the Birds of the World. Vol. 5. Barn-Owls to Hummingbirds (pp. 34–75) Barcelona: Lynx Edicions

- ^

"Tyto alba (Scopoli, 1769)" by The DNA of Singapore. Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research, 2017. URL: https://lkcnhm.nus.edu.sg/dna/organisms/details/800 (accessed on 21 October 2017)

Taylor, I. R. 1993. Age and sex determination of barn owls Tyto alba alba. Ringing & Migration, 14(2), 94-102.

"Barn Owls in summer - rearing young" by The Barn Owl Trust. The Barn Owl Trust, 2017. URL: https://www.barnowltrust.org.uk/barn-owl-facts/owlets-young-barn-owls/ (accessed on 10 November 2017)

Taylor, I. R. 1993. Age and sex determination of barn owls Tyto alba alba. Ringing & Migration, 14(2), 94-102.

"Barn Owl" by All About Birds. The Cornell Lab of Ornithology, 2017. URL: https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Barn_Owl/sounds (accessed on 1 November 2017)

Bruce M.D. 1999. Family Tytonidae (barn-owls). In J. del Hoyo, A. Elliott, and J. Sargatal (Eds.), Handbook of the Birds of the World. Vol. 5. Barn-Owls to Hummingbirds (pp. 34–75) Barcelona: Lynx Edicions

Bruce M.D. 1999. Family Tytonidae (barn-owls). In J. del Hoyo, A. Elliott, and J. Sargatal (Eds.), Handbook of the Birds of the World. Vol. 5. Barn-Owls to Hummingbirds (pp. 34–75) Barcelona: Lynx Edicions

"The daylight activity of Barn Owls" by British Birds. British Birds, 8 July 2013. URL: https://britishbirds.co.uk/article/the-daylight-activity-of-barn-owls/ (accessed on 3 December 2017)

"Tyto alba (Scopoli, 1769)" by The DNA of Singapore. Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research, 2017. URL: https://lkcnhm.nus.edu.sg/dna/organisms/details/800 (accessed on 21 October 2017)

"Western Barn Owl" by Singapore Birds Project. Singapore Birds Project, n.d. URL: https://singaporebirds.com/species/western-barn-owl/ (accessed on 1 November 2017)

Gmelin, J.F. 1788. Caroli a Linné, Systema Naturæ per Regna Tria Naturæ, secundum Classes, ordines, Genera, Species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I, Pars I. Editio Decima Tertia, aucta, Reformata (p. 295) Lipsiæ: Imprensis Georg. Emanuel Beer, 295

"Close Encounters with Owls of Singapore" by Ho Hua Chew. Nature Watch, 1997. URL: http://habitatnews.nus.edu.sg/pub/naturewatch/text/a051a.htm (accessed on 1 November 2017)

"Barn owl a surprise visitor at PM Lee Hsien Loong's office" by Audrey Tan. Straits Times, 21 November 2013. URL: http://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/barn-owl-a-surprise-visitor-at-pm-lee-hsien-loongs-office (accessed on 1 November 2017)

"Visit from the owl: Barn owl flies into PM Lee's office again" by Lee Min Kok. Straits Times, 5 October 2015. URL: http://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/visit-from-the-owl-barn-owl-flies-into-pm-lees-office-again (accessed on 1 November 2017)

"Barn owl visits Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong again, for the third time in five years" by Lydia Lam. Straits Times, 26 August 2017. URL: http://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/barn-owl-visits-prime-minister-lee-hsien-loong-again-for-the-third-time-in-five-years (accessed on 1 November 2017)

Bruce M.D. 1999. Family Tytonidae (barn-owls). In J. del Hoyo, A. Elliott, and J. Sargatal (Eds.), Handbook of the Birds of the World. Vol. 5. Barn-Owls to Hummingbirds (pp. 34–75) Barcelona: Lynx Edicions

Bruce M.D. 1999. Family Tytonidae (barn-owls). In J. del Hoyo, A. Elliott, and J. Sargatal (Eds.), Handbook of the Birds of the World. Vol. 5. Barn-Owls to Hummingbirds (pp. 34–75) Barcelona: Lynx Edicions

"Barn Owl hunting and feeding" by The Barn Owl Trust. The Barn Owl Trust, 2017. URL: https://www.barnowltrust.org.uk/barn-owl-facts/barn-owl-hunting-feeding/ (accessed on 1 November 2017)

Bruce M.D. 1999. Family Tytonidae (barn-owls). In J. del Hoyo, A. Elliott, and J. Sargatal (Eds.), Handbook of the Birds of the World. Vol. 5. Barn-Owls to Hummingbirds (pp. 34–75) Barcelona: Lynx Edicions

"Barn Owl adaptations" by The Barn Owl Trust. The Barn Owl Trust, 2017. URL: https://www.barnowltrust.org.uk/barn-owl-facts/barn-owl-adaptations/ (accessed on 1 November 2017)

"Barn Owl roosting and nesting places" by The Barn Owl Trust. The Barn Owl Trust, 2017. URL: https://www.barnowltrust.org.uk/how-to-manage-land-for-barn-owls/roosting-nesting-places/ (accessed on 3 December 2017)

Robinson, R. A. 2017. BirdFacts: profiles of birds occurring in Britain & Ireland. Thetford: British Trust for Ornithology. [BTO Research Report 407] URL: http://www.bto.org/birdfacts (accessed on 1 November 2017)

"Tyto alba" by Christina Leopold. CABI, 18 September 2012. URL: https://www.cabi.org/isc/datasheet/55507#AF33D426-E964-48DA-9DA1-8ED8F23EDD09 (accessed on 21 October 2017)

"Tyto alba" by BirdLife International. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, 2016. URL: http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/22688504/0 (accessed on 1 November 2017)

Robinson, R. A. 2017. BirdFacts: profiles of birds occurring in Britain & Ireland. Thetford: British Trust for Ornithology. [BTO Research Report 407] URL: http://www.bto.org/birdfacts (accessed on 1 November 2017)

Scopoli, G. A. 1769. "Strix alba". Annus I Historico-Naturalis (in Latin). Leipzig, Sumtib: C. G. Hilscheri. pp. 21–22. URL: http://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/31117670 (accessed on 21 October 2017)

"Tyto alba (Scopoli, 1769)" by GBIF Secretariat 2017. GBIF Backbone Taxonomy, 2017. URL: https://www.gbif.org/species/2497921 (accessed on 21 October 2017)

Wink, M., El-Sayed, A. A., Sauer-Gürth, H., & Gonzalez, J. 2009. Molecular phylogeny of owls (Strigiformes) inferred from DNA sequences of the mitochondrial cytochrome b and the nuclear RAG-1 gene. Ardea, 97(4), 581-591.

"Tyto alba (Scopoli, 1769)" by ITIS. Integrated Taxonomic Information System online database, n.d. URL: https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=177851 (accessed on 14 November 2017)

Peters, J. L. 1931. Check-list of birds of the world. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. pp. 77-82. URL: https://archive.org/stream/checklistofbirds41940pete#page/77/mode/1up (accessed on 21 October 2017)

Wink, M., El-Sayed, A. A., Sauer-Gürth, H., & Gonzalez, J. 2009. Molecular phylogeny of owls (Strigiformes) inferred from DNA sequences of the mitochondrial cytochrome b and the nuclear RAG-1 gene. Ardea, 97(4), 581-591.

Wink, M., El-Sayed, A. A., Sauer-Gürth, H., & Gonzalez, J. 2009. Molecular phylogeny of owls (Strigiformes) inferred from DNA sequences of the mitochondrial cytochrome b and the nuclear RAG-1 gene. Ardea, 97(4), 581-591.