Haliaeetus leucogaster (White-bellied Sea Eagle) (Gmelin, 1788)

Table of Contents

(Image © Rahul Alvares - Approved) [34]

1. Introduction

Singapore, being an urbanised country, is often misunderstood as a country lack of nature and wildlife. However, if one takes a closer look at Singapore, he or she will realize that it is a country filled with very diversified biodiversity. One of such majestic species is the White-bellied sea eagle, which is one of the largest common raptor or bird of prey that can be found in Singapore [1]. It is usually sighted near water across the island, and is a resident species that is present all year round in Singapore. While the population of White-bellied sea eagle in Singapore is relatively stable, the species still face threats (especially anthropogenic threats - more information about the threats can be found in the bottom section of the page), thus efforts should be channeled into the conservation of the species.2. Physical description

(Left: Adult white-bellied sea eagle. Image taken © Rosemary Tully [2] - Pending approval) (Right: Juvenile white-bellied sea eagle. Image © Con Foley [3])

(Photos edited by Tan Yi Jie)

Juvenile white-bellied sea eagle has different coloration as the adult. By the time juvenile reach adult plumage at the 5th year (the time when they start to breed), there will be a gradual transition (across a series of moult) from the brown and cream plumage to the white and grey plumage of the adult. [23]

Some unfamiliar terms: Ceres, lores, tasi

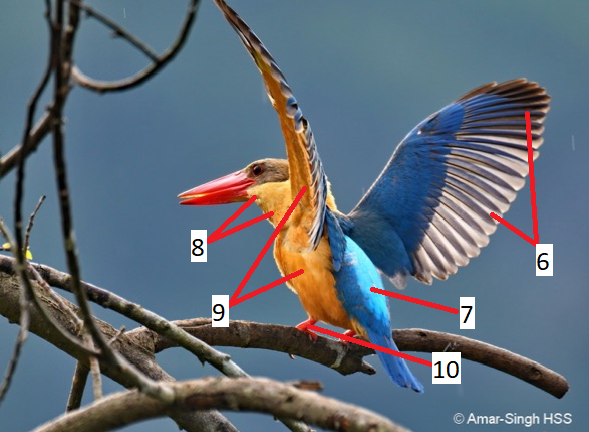

(Image © Rahul Alvares [4] - Approved)

(Edited by Tan Yi Jie) [24]

[25]

Female white-bellied sea eagle is slightly bigger than male white-bellied sea eagle, and this is known as sexual dimorphism. [26]

3. Diagnosis

White-bellied sea eagle can sometimes be confused with the Brahminy kites (Haliastur indus), Egyptian vultures (Neophron percnopterus) and Wedge-tailed eagles (Aquila audax). However, only Brahminy kites can be found in Singapore. [27](Couple of Brahminy kites on perch of tree. Image © Joydeb Chaudhurt [5])

(Image © Rahul Alvares [4] - Approved) |

(Brahminy kite on flight. Image © Romy Ocon [6] - Approved) |

White-bellied Sea Eagle

The white plumage and grey upper parts are diagnostic features |

Brahimy Kite

Easily identify with chestnut plumage and white head, breast and black wing tips |

4. Biology

Feeding habits

White-bellied sea eagle is carnivorous and feed on a wide variety of prey, including reptiles (snakes, turtles and tortoises), fish (sometimes poisonous fish), birds (gulls, terns, cormorants, ducks, geese, and chickens), mammals (bandicoots, wallabies, rodents, rabbits and fruit bats), crustaceans, offal, floating refuse and carrion. It is observed that the white-bellied sea eagle also prey on terrestrial mammals such as grey-headed flying-foxes and short-eared rock-wallabies. [28]

Hunting

White-bellied sea eagle is a skilled hunter, and often engage in a brilliant hunting tactic called still-hunt, a technique to remain still for long periods on a high perch until it locates a potential prey [29]. It can also soar 10-20 metres above the water to forage for food, seldom breaking the surface of the water when it dives down or glides to snatch prey with its large talons and bringing prey back to perch for consumption.

(White-bellied sea eagle gliding down to catch a prey from the water)

Behavior

Being an opportunistic feeder, kleptoparasitism is a common behavior seen in white-bellied sea eagle, which means stealing food from other raptors such as ospreys, kites and even their own kind. Also, during the mating season, both male and female will vocalize courtship calls and then display an acrobatic courtship (click if you want to watch how White-bellied sea eagle perform the stunt!) moves that involve circling, chasing, diving, somersaults and stoops with their talons locked. After finding a mate, the white-bellied sea eagles will defend their breeding territory against other sea eagles. [30]

(White-bellied sea eagle trying to steal prey from Osprey)

Reproduction

(Table summarizing the reproduction aspects of White-bellied sea eagle)

(White-bellied sea eagle incubating eggs, and hatching of eggs)

Lifespan

In the wild, the white-bellied sea eagle is able to live up to 30 years old. [32]

Calls

White-bellied sea eagle calls the most before laying eggs, particularly in the morning and at dusk. Its call is a loud and honking "ank ank ank". During courtship, a faster "ka ka ka" call is heard. Normally, calls of white-bellied sea eagle can be heard up from a distance of 1 km. [21]

5. Habitat

The habitats of White-bellied sea eagle are primarily coastal habitats (including offshore islands), estuaries, lakes, artificial reservoirs, riverbanks, swamps, billabongs, sewage ponds, lagoons, grassland, woodland, rainforest, and sometimes in urban areas i.e. Singapore. They can be found from 0-900 m above sea level but have been recorded as high as 1,700 m in Sulawesi [7] [21].6. Geographical distribution

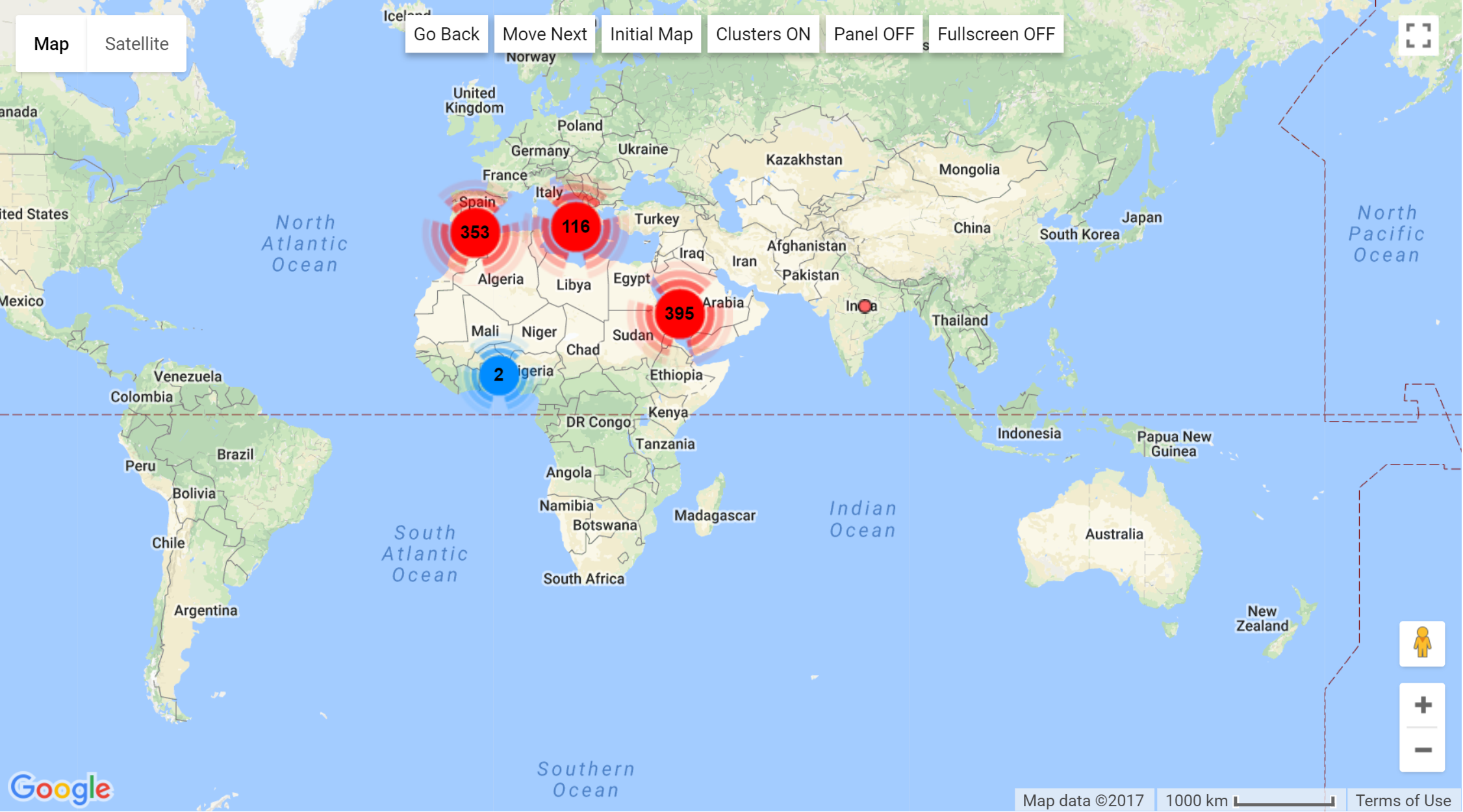

Globally:White-bellied sea eagle resides mostly in countries of the Asian region.

They are native in Australia; Bangladesh; Brunei Darussalam; Cambodia; China; Hong Kong; India; Indonesia; Lao People's Democratic Republic; Malaysia; Myanmar; Papua New Guinea; Philippines; Singapore; Sri Lanka; Thailand; Timor-Leste; Viet Nam. But vagrant in Christmas Island; Taiwan, Province of China [8].

(Yellow markings on the map represents the distribution of White-bellied sea eagle)

(Image © IUCN Red List)

Locally:

White-bellied sea eagle is found throughout Singapore, including the offshore islands [9]. Sites recorded in Bukit Batok Nature Reserve, Bukit Btaok West, Bukit Timah, Changi, Fort Canning, Kent Ridge, Khatib, Kranji, Lower Seletar, Mandai, Nee Soon, Neo Tiew, Pasir Ris, Poyan, Pulau Ubin, Punggol, Saint John's Island, Sembawang, Sentosa, Serangoon, Sime Road, Simpang, Sungei Buloh, Tampines, Upper Seletar [10].

(Map © Google Map)

7. Threats

The table below illustrates the kind of threats that White-bellied sea eagle currently faced. Among these threats, the more prominent ones that occur to the species in Singapore are the increasing human activities (as Singapore is an urbanized country with rising human population and urban development), resulting in the reduction of habitats that are available for White-bellied sea eagle. Having said that, White-bellied sea eagle is very adaptable to changeable environment and also used to the interactions with humans, therefore the species can still survive quite well in Singapore.Some unfamiliar terms: DDT

8. Conservation status

White-bellied sea eagle is listed as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List.The global population number of white-bellied sea eagles is difficult to estimate, but is believed to be between 1,000 and 10,000 individuals. The population is declining and the species is on the verge of becoming Vulnerable. [12]

The conservation status of white-bellied sea eagle in Singapore is Not at risk. Number of individuals counted as of 2005 was 130. Overall trend is also stable [13]. As this data collected was dated 10 years ago, there might be some changes to the state of the population now, and perhaps more can be done to increase the number of individuals for White-bellied sea eagle to above 130.

Although the population of White-bellied sea eagle is considered stable in Singapore, this does not mean that the species needs no conservation. We need to ensure that White-bellied sea eagle is also receiving enough attention in the area of conservation so as to maintain its stable population. There are no known economic importance of white-bellied sea eagle to humans.

9. Conservation efforts

The table below summarises some of the conservation efforts taken by organisation worldwide to protect White-bellied sea eagle. Personally, I feel that Singapore can also step up on the conservation efforts for White-bellied sea eagle, given that it is a majestic species that resides in Singapore, we should do our part to make sure that White-bellied sea eagle can continue to flourish in an unfamiliar environment now that there are lesser forests available now for the species to live in. Students and supporters of avian conservation, especially the bird watchers, can make contributions to keeping this beautiful species safe and protected in review of the conservation efforts stated in the table below. Wildlife organisations in Singapore should also help conduct surveys frequently to monitor the population of the species.Apparently, the conservation efforts made by Australia is quite successful in bringing the population of White-bellied sea eagle back.

[15]

10. Taxonomy and systematics

ClassificationKingdom: Animalia (Animals)

Phylum: Chordata (Chordates)

Subphylum: Vertebrata (Vertebrates)

Class: Aves (Birds)

Order: Falconiformes (Diurnal birds of prey)

Family: Accipitridae (Eagles, hawks, and kites)

Genus: Haliaeetus (Fish eagles)

Species: Haliaeetus leucogaster (White-bellied sea eagle) [16]

Original description

The white-bellied sea eagle was first described by Johann Friedrich Gmelin in 1788. [17]

(Image © Penny Olsen) [33] - Pending approval

Taxonomy

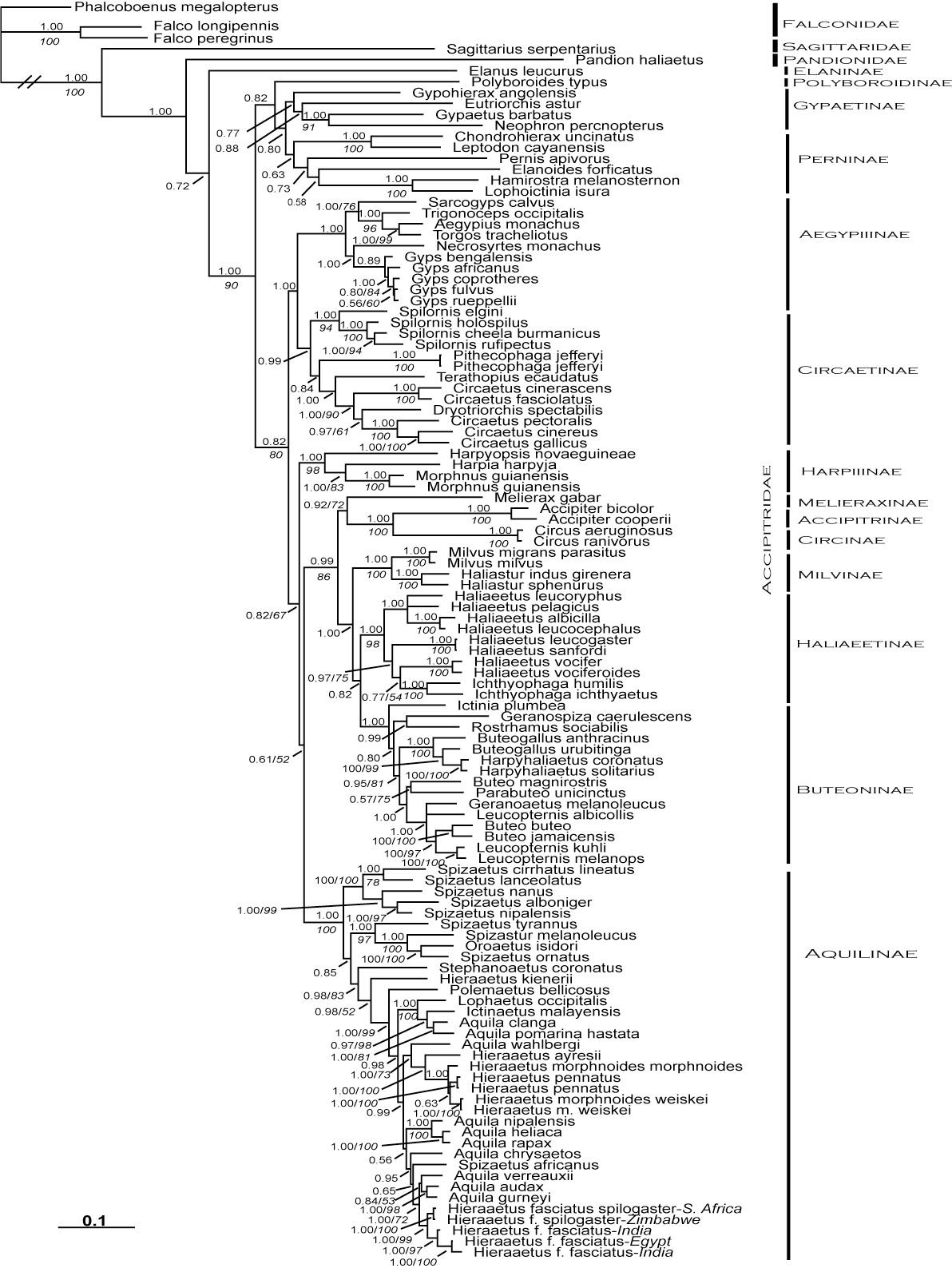

White-bellied sea eagle (Haliaeetus leucogaster) is monotypic and forms a clade with Sanford's sea eagle (Haliaeetus sanfordi), African fish eagle (Haliaeetus vocifer) and Madagascar fish eagle (Haliaeetus vociferoides) as shown in the phylogenetic tree below. White-bellied sea eagle also forms a superspecies with Sanford's sea eagle [22]. It is found that there is only a small genetic difference (0.3%) between White-bellied sea eagle and Sanford's sea eagle, thus predicting that Sanford's sea eagle has recently just evolved from White-bellied sea eagle. The genetic difference is equivalent to what is usually found among members of the same species. However, they are not known to come into contact with each other, hence somewhat suggesting that they might be parapatric. Furthermore, the two are classified differently by several authorities because of their differences in behavior and morphology. The eagle genus Haliaeetus is closely related to the kite genera Milvus and Haliastur. [18] [19]

Lerner (2007) mentioned in her studies that phylogenetic studies using molecular data sets are essential to produce a more congruent results in phylogenies. Phylogenies are needed to delineate the genetic and overall biological diversity. An evident phylogeny of Accipitridae can provide reliable information into the evolution of the diverse accipitrid life-styles, and the biogeographic history of the family. [20]

To reconstruct phylogenies, maximum parsimony and Bayesian inference were used, carried out by PAUP* 4.0b10 and MrBayes 3.01 program respectively, with 500 bootstrap replicates. (For more information about what data was used, please click!)

(Image © Heather R.L Lerner)

Phylogeny for Accipitridae taxa inferred from mitochondrial cyt-b and ND2 sequences. Topology shown is the Bayesian inference majority rule tree. Bayesian posterior probability values are shown above branches and Maximum Parsimony bootstrap values (>50%) are shown in italics below the branches. (Taken from Heather R.L Lerner) [32]

(Zoom in of phylogenetic tree for genus Haliaeetinae) (Image © Heather R.L Lerner; Edited by Tan Yi Jie)

We can see that the Maximum Parsimony bootstrap values for White-bellied sea eagle (Haliaeetus leucogaster) is 100, which shows that the species is very well supported as a monophyletic group. Also, it can be seen that the branch length for the superspecies (Haliaeetus leucogaster and Haliaeetus sanfordi) is almost negligible. Since the branch length is proportionate to evolutionary change, this shows that the evolutionary change is very short, which corresponds to the recent evolution of Sanford's sea eagle (Haliaeetus sanfordi) from White-bellied sea eagle.

11. Glossary

Ceres: Fleshy area at bill base enclosing nostrilsDDT: Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, an insecticides with detrimental environmental impacts

Lores: The area between eye and bill

Monotypic: Monotypic species consists of a single population that is not divided into subspecies

Moult: Periodic replacement of feathers by shedding old feathers while producing new ones

Parapatric: No extrinsic barrier to gene flow

Plumage: A bird's feathers collectively

Superspecies: A monophyletic group of entirely or essentially allopatric species that are too distinct to be included in a single species

Tarsi: Lower segment of legs, before toes

12. Useful links

Birds topography: http://aaa-webs.com/whitedoves/Love_Doves/aboutdoves/glossary.htm13. References

All information adapted from:[1] [24] The Birds of NUS (2012). White-bellied Sea Eagle. Retrieved from: https://nusavifauna.wordpress.com/2012/07/28/white-bellied-sea-eagle/ (Accessed on 8 November 2016)

[2] Tully, R. (2009). Image retrieved from http://nzbirdsonline.org.nz/species/white-bellied-sea-eagle (Accessed on 7 November 2016) - Pending request

[3] Foley, C. Birds of prey. Image retrieved from http://singaporebirds.blogspot.sg/2012/05/birds-of-prey-order-falconiformes-birds.html (Accessed on 7 November 2016) - No contact

Joydeb Chaudhury

[4] [34] Alvares, R. Image retrieved from http://rahulalvares.com/2014/09/white-bellied-sea-eagle/ (Accessed on 7 November) - Permission granted

[5] Chaudhurt, J. (2013). Couple of Brahminy kite. Image retrieved from http://www.treknature.com/gallery/Asia/India/photo284316.htm (Accessed on 9 November) - No contact

[6] Ocon, R. Image retrieved from http://www.romyocon.net/2013/04/the-tough-to-expose-brahminy-kite.html (Accessed on 7 November 2016) - Permission granted

[7] [16] [23] [26] [27] [28] [30] [31] Zahm, S. (2015) "Haliaeetus leucogaster" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved from http://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Haliaeetus_leucogaster/ (Accessed on 6 November 2006)

[8] [12] BirdLife International (2012). Haliaeetus leucogaster. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2012. Retrieved from http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/22695097/0 (Accessed on 9 November)

[9] [17] [29] Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum (2016). Haliaeetus leucogaster. Retrieved from http://lkcnhm.nus.edu.sg/dna/organisms/details/25 (Accessed on 7 November 2016)

[10] [13] [14] Lim, K.C. and Lim, K.S. (2009). Wild Birds and Bird Habitats. A review of the Annual Bird Census 1996 - 2005. Bird Group Nature Society (Singapore).

[11] [25] Department of the Environment (2016). Haliaeetus leucogaster in Species Profile and Threats Database, Department of the Environment, Canberra. Retrieved from http://www.environment.gov.au/sprat. (Accessed 9 November 2016)

[15] Wildscreen Arkive (n.d.) White-bellied sea eagle (Haliaeetus leucogaster). Retrieved from http://www.arkive.org/white-bellied-sea-eagle/haliaeetus-leucogaster/image-G110258.html (Accessed on 7 November 2016)

[18] Debus, S., Kirwan, G.M. & Christie, D.A. (2016). Sanford's Sea-eagle (Haliaeetus sanfordi). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. Retrieved from http://www.hbw.com/node/52982 (Accessed on 9 November 2016)

[19] Global Raptor Information Network. 2016. Species account: White-bellied Sea Eagle Haliaeetus leucogaster. Retrieved from http://www.globalraptors.org (Accessed on 9 Nov. 2016)

[20] [32] Lerner, H.R.L. (2007). Molecular Phylogenetics of Diurnal Birds of Prey in the Avian Accipitridae Family.

[21] [22] The Eagle Directory. White-bellied Sea eagle - Haliaeetus leucogaster. Retrieved from http://www.eagledirectory.org/species/white_bellied_sea_eagle.html (Accessed on 7 November)

[33] Olsen, P. (2015). Australian Predators of the Sky. National Library of Australia. Retrieved from https://books.google.com.sg/haliaeetusleucogaster (Accessed 10 November) More information at https://www.nla.gov.au/ - Pending request