Big-bellied Tylorida Spider

横 带 隆 背 蛛

Table of Contents

|

| Tylorida ventralis (female). (Photo by Rayson Lim (C)) |

*Click on images to view them at higher resolution in new window**

Introduction

Tylorida ventralis (Thorell, 1877) belongs to the family Tetragnathidae. They are long-jawed orb weavers with long legs because they have a distinctive cherlicerae that are long and wide, and their webs are shaped delicately like an orb with open hubs. Under the genus Tylorida Simon, 1894, they can be easily distinguished from other genera of the sub-family Leucauginae from their first pair of legs, which are longer than their second pair by a ratio of more than 1.6.

Contrary to common beliefs that female spiders are cannibalistic and reluctant to participate in sex, the sexual behaviour in T. ventralis offered a complete twist to this notion, making them one of the “horniest” spiders.

Biology

Unusual sex in T. ventralis

Tylorida ventralis mating pair (male: left, female: right) (Photo taken by Nicky Bay (C))

Copulation in all spiders with the exception of the harvestman (Order: Opiliones) occurs indirectly through a process called sperm induction. This process involves the transference of semen from the genitalia at the ventral side of its abdomen into its palps situated in front of its head first, before inserting the palp into the epigynum of the female located at the ventral side of the abdomen.[11] Usually, the male will chew on its palps, which by wetting them may help with the absorption of the semen.

Male (left) flexing his palp on the chelicera and approaching the female (right). (Photo taken by Nicky Bay (C))

Copulation in T. ventralis usually occurs within the female's orb-web where the male will approach the female in the web and flexes his palps in a rotatory manner, which is normally a prelude to sperm induction and copulation. Contrary to the conventional notion that female spiders are reluctant or passive in sexual advances by the males and is extremely aggressive or even cannibalistic towards their partners, a study by Mafham and Cahill [10] observed that the T. ventralis females showed positive response to the presence of males and will actively participate in or even initiate copulation.

A male (left) T. ventralis trying to insert the palp into the female's epigynum (right). (Photo taken by Nicky Bay (C))

Moreover, insertion of the palp (containing the sperms) into the epigynum in T. ventralis can be repeated hundreds of times during the mating period which can last for as long as 10 hours.[10] This behaviour is uncommon in other species such as Tetragnatha extensa and Micrommata virescens, which will only insert its palp once.

Palp being inserted into epigynum (Male = right, Female = left). (Photo taken by Nicky Bay (C))

There are two possible explanations for this bizarre copulation behaviour in T. ventralis. Firstly, this behaviour seems to constitute an unusual form of mate-guarding and will prevent any further insemination by other males, thus confering higher sperm priority. Secondly, by staying in the web longer, the male derives benefits by stealing a proportion of the food meant for ovarian maturation by the female. At the same time, the female also benefits from the extended copulation by reducing the risk of predation or capture (50% reduction).[10]

After insemination, the female is able to retain the sperm mass outside of the uterus in a specialized structure (spermathecae) until the eggs are ready for fertilization.[2] Thus, they are able to lay several batches of eggs. She will then protect the eggs by spinning a soft layer of fine yellow silk (Tubiliform silk) as shown in the photo below. In most cases, the mother will care for the offsprings and actively secure food for her brood until they hatch.

|

| Egg sac of T. ventralis (Photo by Rayson Lim (C)) |

Physiology of feeding and digestion

Digestion of their prey occurs externally where once the prey has been subdued via wrapping them with silk, it will cut and mash the prey with its cheliceral teeth and pour in enzymes derived from the front end of the alimentary canal. Once the internal organs of the prey starts to liquify, it will be sucked out and more enzymes will be introduced until the internal contents have been fully digested and consumed. The liquified content will then be ingested into the midgut due to the action of the sucking stomach. Any remaining particulate solids will be filtered out through the bristles around the mouth as well as by a filter system in the throat. The final stages of the digestion and adsorption of food occur in the midgut.[11]

Based on personal observation, T. ventralis seldom feed by trapping its prey using its web. Instead, it lies motionless on its web, sensing the web tension with its trichobothrial and when the prey is within striking range, it will grab its prey and wrap it with silk.

Web construction and foraging

T. ventralis are orb-web spiders and their web type can be classified under aerial ladder-webs.[6] These webs are often built in open vegetation such as heathland and forests. T. ventralis will spend most of its time resting at the web's open-hub, monitoring the tensions and vibrations of the web using its sensitive trichobothrial hairs on its legs. The web hub is usually situated at the extreme top of the web, which allows equal access times to all parts of the web because it can run faster downhill than climbing upwards [6, 11]. Although little is known about the foraging ecology of T. ventralis, a study conducted on T. ventralis mating behaviour has shown that the females usually construct or renew their web in the early morning, indicating that it may be the most productive period or their usual feeding period. [10]

Back to Top

Distribution

Resting posture outstretching its first pair of legs (Photo by Rayson Lim (C)) (Photo by Rayson Lim (C))

Habitat

Tylorida ventralis are commonly found in forests and heathland, usually hiding under leaves or camouflaging against a branch. However, they can also be found in the urban areas such as in the water ducts under the streets as recorded by Jäger and Praxaysombath in Laos. [7]

In their resting position, they can be found on orb-webs with their first pair of legs outstretched forward and close together, camouflaging like a twig or stick on the web.

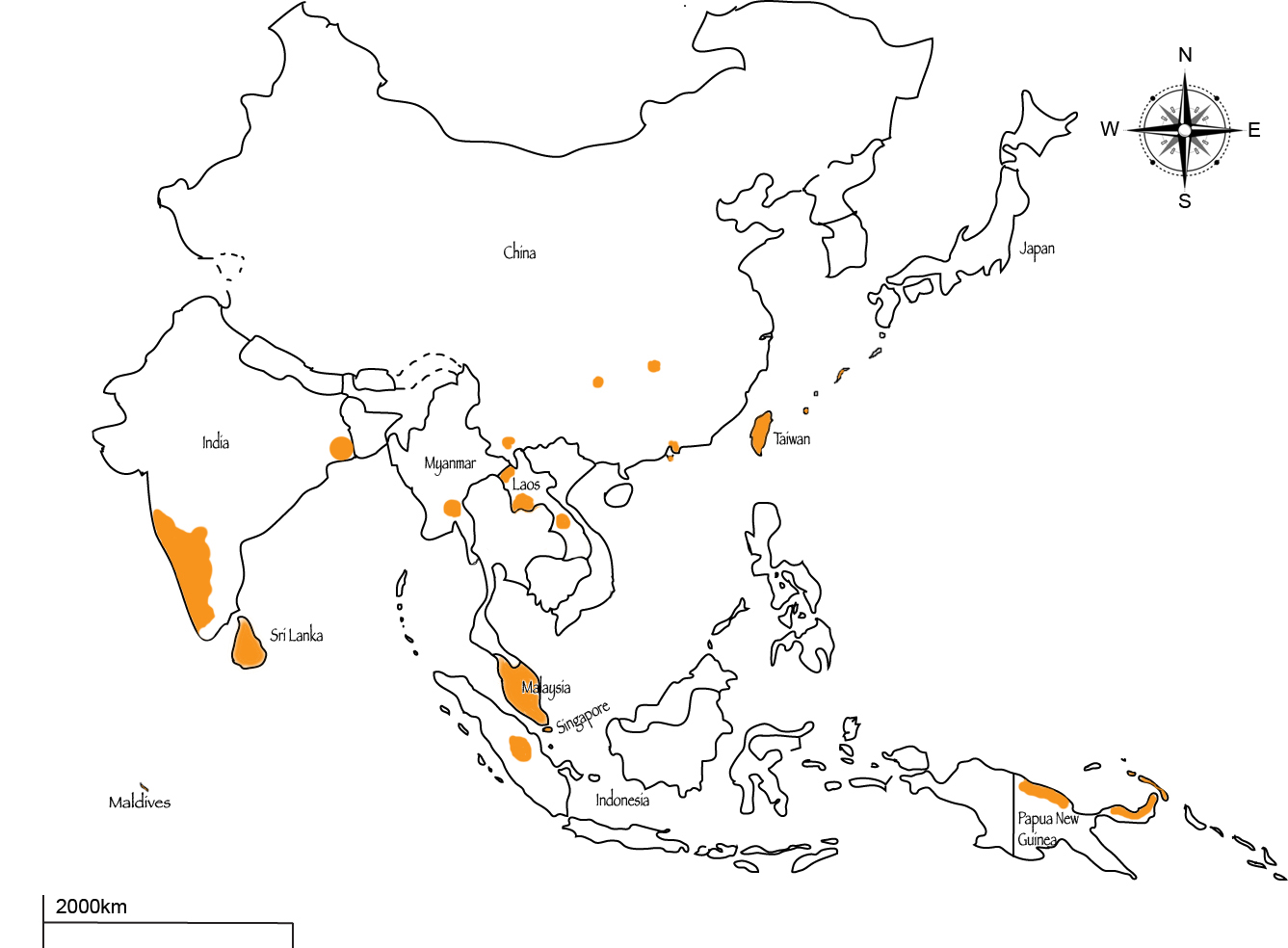

Countries: India; Sri Lanka; Southern China; Taiwan; Japan; Papua New Guinea; Myanmar; Laos; Malaysia; Singapore; Indonesia

Map showing the distribution of T. ventralis (Orange parts indicate presence of T.ventralis). The distribution is based on the information of examined specimen by various authors as shown in Table 1.

Description locality and specimen information

Table 1 shows the information of collected specimens in various locality.

| Country |

Year |

Specimen |

Catalog |

Collector |

Locality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indonesia[5] |

1877 |

Male & female |

Unknown |

Unknown |

Kendari, Sulawesi (formerly known as Celebes): TYPE LOCALITY |

| Myanmar (Burma)[22] |

1887 |

Unknown |

Specimen in British Museum (Natural History) |

Oates, E.W. |

Tharrawaddy, Rangoon |

| Maldives[14] |

1904 |

Male & female |

Unknown |

Gardiner, J.S. |

Minikoi; Ereadu & Miladumadulu |

| India[23] |

1956 |

5 females |

National Collection, ZSI, 25.xi.1956 |

Tikader, B.K. |

Dhakuria, Calcutta |

| India[8] |

2000 |

1 female |

National Collection, ZSI, 12.vii.2000 |

Sunil Jose, K. |

Bhoothathankettu, Kerala |

| Papua New Guinea[5] |

1959 |

1 female |

RMNH, 8.ix.1959 |

Vervoort, W. |

Kouh, Digoel, West New Guinea |

| Papua New Guinea[5] |

1959 |

1 female |

RMNH, 2.vii.1959 |

Star Mountains Expedition |

Ok Bon, West New Guinea |

| Papua New Guinea[5] |

1909 |

1 female |

ZMH, 12-16.i.1909 |

Duncker, G. |

Langemak Bay, East New Guinea |

| Papua New Guinea[5] |

1962 |

1 male |

ZMK, 21.iii.1962 |

Noona Dan Expedition |

Lavongai, Banatam, Bismarck Archipelago |

| Singapore[17] |

1989 |

1 female & 1 male |

RMBR, ZRC 1994.77-18 |

Unknown |

Lim Chu Kang mangroves |

| Laos[7] |

2004 |

1 female |

SMF 58723-121 |

Jӓger, O. & Vedel, V. |

Muang Sing, Nam Det, Luang Nam Tha Province |

| China[27] |

1988 |

5 females & 4 males |

Specimen in Museum of Hebei University |

Yan, H.M. |

Chang Sha city, Hunan Province |

| China[27] |

1990 |

3 females & 2 males |

Specimen in Museum of Hebei University |

Zhu, M.S. |

Fan Jing Mountain, Guizhou Province |

| China[27] |

1998 |

8 females & 2 males |

Specimen in Museum of Hebei University |

Wong, X.P. |

Taiping Mountain, Hong Kong |

| China[27] |

1990 |

3 females & 2 males |

Specimen in Museum of Hebei Univeristy |

Zhu, M.S. |

Yunan Province |

| Japan[19] |

2003 |

5 females & 2 males |

NSMT-Ar 5582-5583 |

Tanikawa, A. |

Okinawa Prefecture |

ZSI - Zoological Survey of India

RMNH - Rijksmuseum van Natuurlijke Historie, Leiden

ZMH - Zoologisches Museum Hamburg

ZMK - Zoologiske Museum København

RMBR - Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research

ZRC - Zoological Reference Collection

SMF - Research Institute Senckenberg, Frankfurt am Main, Germany

NSMT - National Science Museum, Tokyo

Back to Top

Etymology

Synonyms

| Name |

Description |

Remarks |

Accepted |

| Meta ventralis |

Thorell, 1877b. Annali. Mus. civ. Genova, 10: 423. |

Original description |

X |

| Argyroepeira ventralis |

Thorell, 1887. Annali. Mus. civ. Genova, 25: 138. Workman, 1896. Malays. Spid., : 65. Pocock, 1900. Fauna Brit. India, Arachn.,: 216 |

X |

|

| Leucauge ventralis |

Pocock, 1904. Fauna and Geography of the Maldive and Laccadive Archipelagoes, Arachn. Long., 2: 800. Tikader, 1962. J. Linn. Soc., 44(300): 566. |

Transferred from Argyroepeira |

X |

| Anopas ventralis |

Archer, 1951. Am. Mus. Novit., 1502: 7. |

Transferred from Leucauge ventralis |

X |

| Leucauge sphenoida |

Wang, 1991. ACTA: Ootaxonomica Sinica, 16: 157. Song, Zhu & Chen, 1999. Hebei Science and Technology Publishing House: 216. |

Described wrongly |

X |

| Tylorida ventralis |

Chrysanthus, 1975. Further notes on the spiders of New Guinea II (Araneae, Tetragnathidae, Theridiidae): 31 (transferred from Anopas). Song, Zhu & Chen, 1999. Hebei Science and Technology Publishing House: 223. Tanikawa, 2004. Acta Arachnologica, 53(2): 153. |

Transferred from Anopas ventralis |

O |

Back to Top

Diagnosis

There are total of 9 described species of Tylorida: T. culta, T. cylindrata, T. mengla, T. mornensis, T. seriata, T. stellimicans, T. striata, T. tianlin and T. ventralis.

Among these 9 species, T. cylindrata and T. ventralis resembles each other closely with similar body-shape and colour. However, they can be distinguished from each other through 4 differences:

1) T. ventralis(♀: 6.75 ~ 7.38mm, ♂: 5.49 ~ 6.21mm) is much smaller than T. cylindrata (♀: 12.24 ~ 13.77mm, ♂: 10.98mm).

2) Depression at female epigynum of T. ventralis is situated close to the epigastric furrow whereas the depression is situated far from the epigastric furrow in T. cylindrata.

3) Epigynum is posteriorly narrowing in T. cylindrata but not in T. ventralis.

4) Horn-shaped guiding lamellae at the tip of the conductor (on the palp) of T. ventralis is shorter than T. cylindrata.

5) Ridges on the retrolateral surface of the T. ventralis male chelicera is absent but is present in T. cylindrata.

[27]

Back to Top

Description

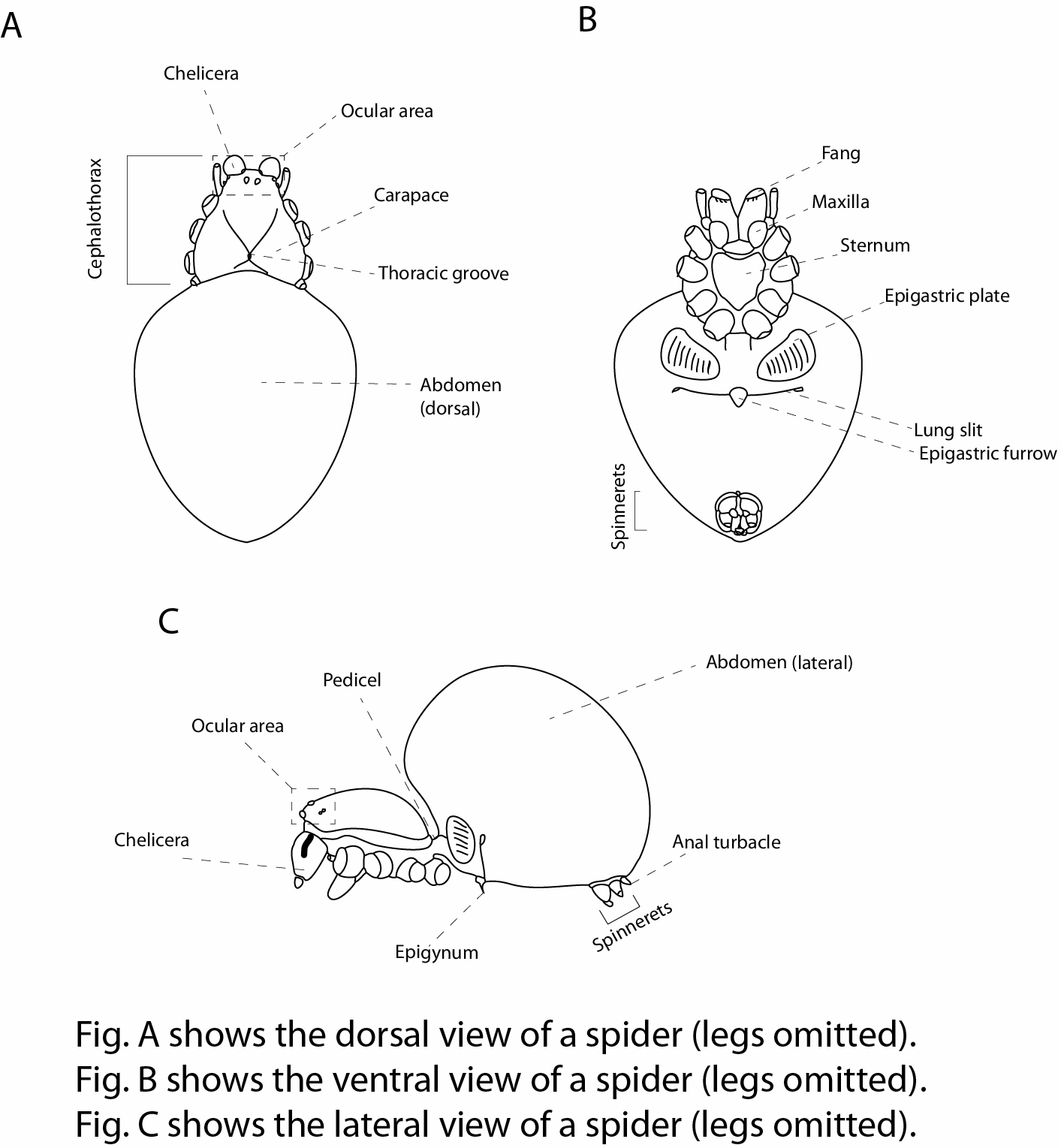

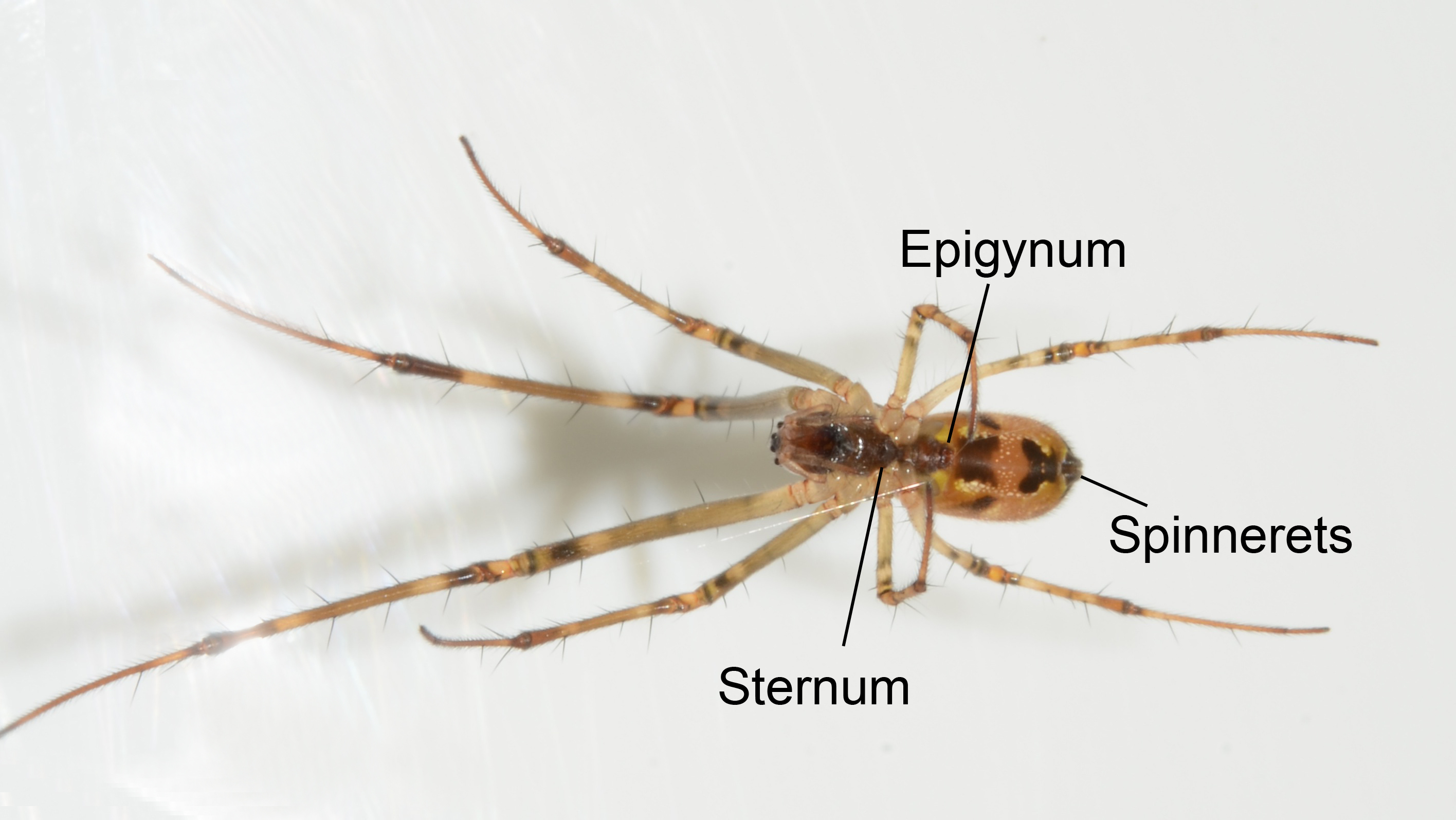

Anatomical terms

Illustrated anatomical terms (Rayson (C))

Sexual dimorphism

Male and female are similar in shape, colour and ocular area arrangement with the exception of:1) Size (♂: 5.49~6.21mm, is slightly smaller than ♀: 6.75~7.38mm).

2) Legs of males are longer and thinner than females.

3) Promargin of chelicera with 3 teeth (♀ & ♂) but retromargin has 4 - 5 teeth (♀) and 4 teeth (♂).

[27]

|

| Lateral view of a male T. ventralis waving its palps (Photo by Rayson (C)) |

|

| Anterior view of male T. ventralis (Photo by Rayson Lim (C)) |

|

| Ventral view of a male T. ventralis hanging from a petiole (Photo by Rayson (C)) |

|

| Lateral view of a female T. ventralis (Photo by Rayson (C)) |

|

| Anterior view of female T. ventralis (Photo by Rayson Lim (C)) |

|

| Ventral view of a female T. ventralis hanging on its web (Photo by Rayson (C)) |

Cephalothorax

|

| Anterior view of female T. ventralis (Photo by Rayson Lim (C)) |

|

| Dorsal view of a female T. ventralis (Photo by Rayson Lim (C)) |

Carapace

- Longer than wide and covered in pubescence and hairs

- Grey with brown patches

- Moderately flat with cephalic region slightly elevated than the thoracic region

- Thoracic region have a posterior trifid deep groove

- Single dark brown longitudinal line on each side of the carapace

Ocular area (eyes)

|

| Ocular area of T. ventralis (Photo by Rayson Lim (C)) |

|

| Ventral view of a female T. ventralis (Photo by Rayson Lim (C)) |

- Ocular quad is longer and wider at the posterior row where the anterior row is placed closer together

- Anterior median eyes are slightly larger than the posterior median eyes

- Lateral eyes are sub-equal to the posterior median eyes and they occur closely (in pair) on slightly prominent black tubercles

- Both rows of eyes are recurved but posterior row only slightly recurved

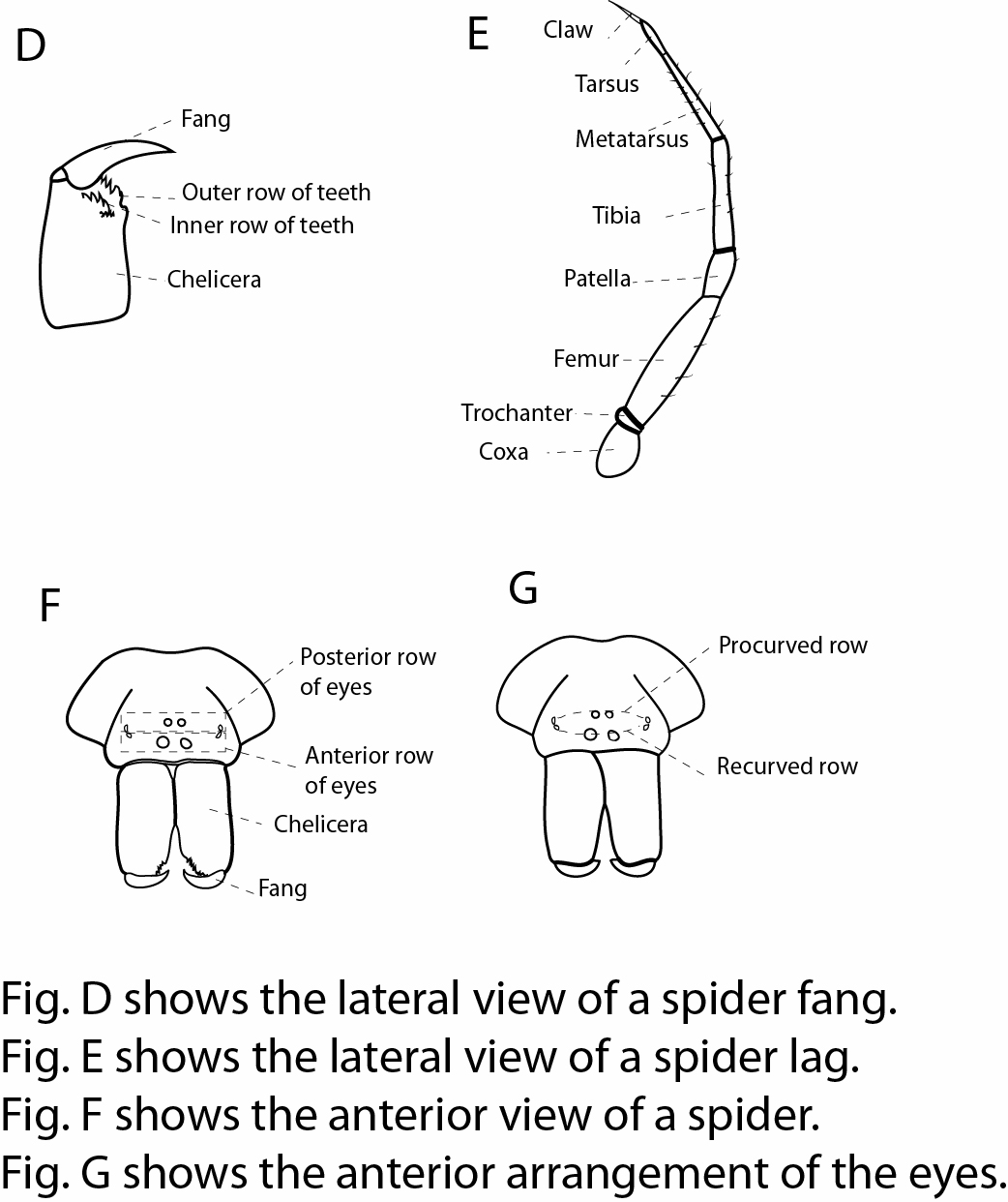

Sternum (ventral side)

- Sternum is brown and heart-shaped, tapering behind and covered with hairs

Sternum of a female T. ventralis (ventral side) (Photo by Diego (C))

Feeding parts

- Maxillae longer than wide, broad distally and is dark brown

- Cherlicerae is brownish-yellow and long, and has 3 teeth at the promargin

Legs

- Legs pale-yellow in colouration, long and slender, and covered with hairs and scanty spines

- First pair of legs are the longest and always stretched forward in its resting position

- First two pairs of Tibiae and Metatarsi have indistinct brown bands

- Fourth Femora have a double fringe of trichobothrial on the prolateral surface of the proximal half

|

| Epigynum on female T. ventralis (Photo by Rayson Lim (C)) |

- Elongated abdomen that is tapered at the posterior end

- Anterior end is high and roughly forms a right angle

- Posterior end forms an indistinct caudal tubercle

- Dorsum of abdomen filled with brown patches and reticulated silvery-white specks

- Ventral side has a mid-longitudinal broad brown patch surrounded by a single white

- A few brown patches present laterally adjacent to the spinnerets

- Epigynum (female) is brown and plate-like with a distinct conspicuous rim

Back to Top

Literature and references

- 陳世煌. 1996. 台灣地區蜘蛛名錄. 台灣省立博物館年刊

- Álvarez-Padilla, F., and G. Hormiga. 2011. Morphological and phylogenetic atlas of the orb-weaving spider family tetragnathidae (araneae: araneoidea). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 162:713–879.

- Archer, A. 1951. //Studies in the orbweaving spiders (Argiopidae). I//. American Museum novitates; no. 1487. The American Museum of Natural History:1–52. New York.

- Chrysanthus, F. 1971. //Further notes on the spiders of New Guinea I (Argyopidae).// Zoologische Verhandelingen: 52.

- Chrysanthus, F. 1975. //Further notes on the spiders of New Guinea II//. Zoologische Verhandelingen: 50

- Harmer, A. M. T., and M. E. Herberstein. 2010. Functional diversity of ladder-webs: moth specialization or optimal area use? Journal of Arachnology 38:119–122.

- Jäger, P., and B. Praxaysombath. 2009. Spiders from Laos: new species and new records (Arachnida: Araneae). //Acta Arachnologica// **58**:27–51.

- Jose, S. 2005. A faunistic survey of spiders (araneae: arachnida) in Kerala//. PhD. Mahatma Gandhi University, India.

- Jose, S. K., A. V. Sudhikumar, S. Davis, and P. A. Sebastian. 2008. Preliminary studies on the diversity of spider fauna (Araneae: Arachnida) in Parambikulam Wildlife Sanctuary in Western Ghats, Kerala, India. //Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society//. **105**:264–273.

- Mafham, K. P., and A. Cahill. 2000. Female‐initiated copulations in two tetragnathid spiders from Indonesia: Leucauge nigrovittata and Tylorida ventralis. Journal of Zoology 252:415–420.

- Mafham, K.P. and R.P. Mafham. 1996. The natural history of spiders. Ramsburg, Marlborough: The Crowood Press Ltd.

- Norma-Rashid, Y., and D. Li. 2009. A Checklist of Spiders (Arachnida: Araneae) From Peninsular Malaysia Inclusive of Twenty New Records. //Raffles Bulletin of Zoology//**. 57**:305–322.

- Pocock, R.I. 1900. //The fauna of British India, including Ceylon and Burma.// Arachnida. London: 279pp.

- Pocock, R.I. 1904. //Fauna and Geography of the Maldive and Laccadive Archipelagoes, Arachn. Long. **2**: 800.

- Siliwal, M., and S. Molur. 2007. Checklist of spiders (Arachnida: Araneae) of South Asia including the 2006 update of Indian spider checklist. //Zoos' Print Journal//**. 22**:2551–2597.

- Siliwal, M., S. Molur, and B. K. Biswas. 2005. Indian spiders (Arachnida: Araneae): updated checklist 2005. //Zoos' Print Journal.// **20**:1999–2049.

- Song, D., J. Zhang, and D. Li. 2002. A checklist of spiders from Singapore (Arachnida : Araneae). //Raffles Bulletin of Zoology//. **50**:359–388.

- Song, D.X., M.S. Zhu and J. Chen. 1999. The spiders of China. Shijiazhuang: Hebei Science and Technology Publishing House. 640 pp.

- Tanikawa, A. 2005. Japanese spiders of the genus Tylorida (Araneae: Tetragnathidae). //Acta Arachn Tokyo.// **53**:151–154.

- Thorell, T. 1877. Studi sui Ragni Malesi e Papuani. I. Ragni di Selebes raccolti nel 1874 dal Dott. O. Beccari. Ann. Mus. civ. stor. nat. Genova. 10: 341-637.

- Thorell, T. 1887. Viaggio di L. Fea in Birmania e regioni vicine. II. Primo saggio sui ragni birmani. Ann. Mus. civ. stor. nat. Genova. 25: 5-417.

- Thorell, T. 1895. Descriptive catalogue of the spiders of Burma, based upon the collection made by Eugene W. Oates and preserved in the British Museum. By T. Thorell. London: 406 pp.

- Tikader, B. 1962. Studies on some Indian spiders (Araneae: Arachnida). Journal of the Linnean Society of London. 44(300): 561–584.

- Tikader, B. 1982. The fauna of India, Spiders: Araneae Vol. II. Calcutta: Zoological Survey of India. 2: 536 pp.

- Wong, J. F. 1991. On the Spiders of the Family Tetragnathidae in South China (Arachnida: Araneae). //Acta Zootaxonomica Sinica//. **16**:153–162.

- Workman, T. 1896. Spiders: Malaysian Spiders. Belfast: 104 pp.

- Zhu, M., C. Wu, and D. Song. 2002. A revision on the Chinese species of the genus Tylorida (Araneae: Tetragnathidae). //Acta Arachnologica Sinica//. **11**:25–32.

Back to Top

Discussion area

| Subject | Author | Replies | Views | Last Message |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Comments | ||||