Say hello to Singapore's (unofficial) national bird!

Table of Contents

|

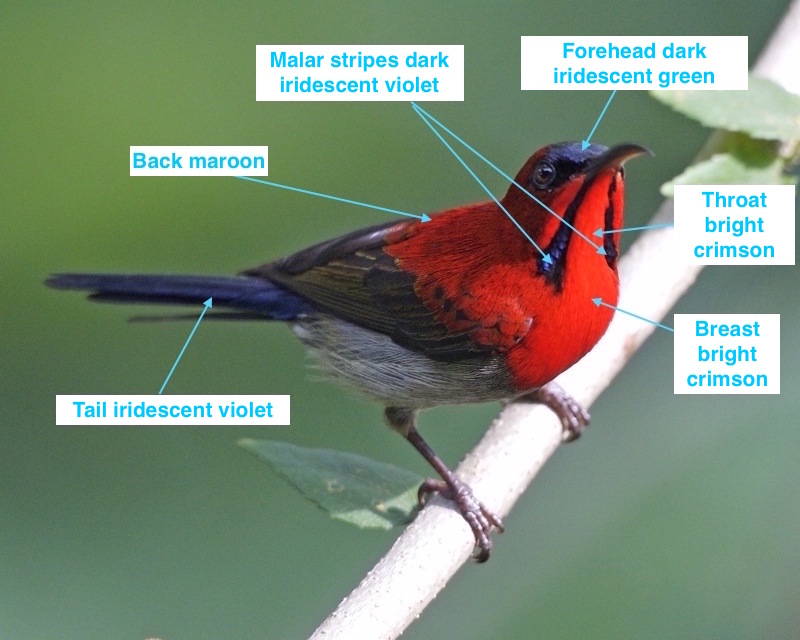

| Figure 1. Photo of a Crimson Sunbird by Mike Prince (2011) © |

1. Introduction

1.1 A brief description

The crimson sunbird is a tiny sunbird that belongs to the family Nectariniidae. It can be found in the tropical regions of southern and south-eastern Asia, ranging from north-western India to eastern Indonesia. Its preferred habitats are forests and plantations. It is generally nectarivorous, but may also feed on insects[1] .

1.2 Singapore's unofficial national bird

In 2002, the crimson sunbird received the most votes to be Singapore's national bird in a poll started by Nature Society Singapore (the white-bellied sea eagle came second). Voters felt that its small size and bright red plumage were good representatives of the country. On 1st November 2015, Dr Shawn Lum, president of Nature Society Singapore, publicly announced that the crimson sunbird had been declared the national bird of Singapore. The following day, however, Dr Lum clarified that this was not official and was still pending an agreement with three government departments. This remains the case till today [2] .

1.3 Not a hummingbird

Crimson sunbirds and other sunbirds are often mistaken for hummingbirds due to their similar appearance in terms of size and colouring. However, this is actually a result of

convergent evolution, as both fulfil similar ecological niches by feeding on nectar and therefore play a key role in pollination. Sunbirds and hummingbirds are not closely related at all - hummingbirds' closest cousins are actually swifts and nightjars[3] . In addition, sunbirds and hummingbirds do not coexist anywhere in the world. Sunbirds are found in Asia, Africa and Australia while hummingbirds are found only in North and South America[4] . So the next time you're confused as to whether a bird you've seen is a sunbird or a hummingbird, all you have to do is know which continent you're on!

2. Etymology

Etymology describes how a species got its scientific name. For the crimson sunbird, the Latin species epithet siparaja was given to it by Sir Stamford Raffles based on the Malay name 'burong sepah raja'. 'Burong' translates to 'bird', 'sepah' refers to the sweet juice of the betel nut, and 'raja' means 'king'[5] .

3. Biology

3.1 Habitat

The crimson sunbird occupies a large variety of habitats. It can be found in various forest types (eg. riverine, peatswamp), typically at the forest edge, but also in more open areas such as grasslands, scrub, mangroves, woodlands, parks or gardens. With regards to altitude, it is usually found at heights of below 915m, but can be found at altitudes of 1,690m in Bhutan and 1,800m in Nepal during the summer[6] . Below is a video of a male crimson sunbird in MacRitchie Reservoir:

3.2 Behaviour

Crimson sunbirds may forage either low or in the canopy; singly, in pairs or in larger family parties. Males often sing from exposed branches in the canopy and can get extremely aggressive with each other as they often establish feeding territories on flowering shrubs or trees. Crimson sunbirds can also reduce their metabolism at night depending on the ambient temperature (reduce by 54% at 5°C, and 62% at 25°C)[7] .

3.3 Feeding habits

The crimson sunbird feeds primarily on nectar. It seeks out flowers with high sugar content and pierces the base of the corolla[8] to get to the nectar directly. It plays an important ecological role in pollination, as many native flowering plants rely on sunbirds for this purpose. Many plants have tubular-shaped flowers that actually exclude other pollinators such as bees from feeding on them, just so that the crimson sunbird can do so. The crimson sunbird may also feed on insects and spiders during the breeding season to feed its young[9] .

|

| Figure 2. Photo of crimson sunbird feeding on nectar. Notice how it pierces the base of the corolla to get to the nectar directly. Photo taken by Lip Kee (2007) © |

3.4 Breeding and nesting

The male crimson sunbird is known to perform a mating display, during which it not only sings, but also fluffs out its tertial feathers to display its yellow rump which usually remains unexposed. Watch it in the video below:

The nest of a crimson sunbird couple is usually attached to palm fronds. It is made of vegetable down, cobweb, grass, roots, and may be found under overhanging banks, such as in Gunung Kinabalu, Sabah[10] .

Egg-laying months are typically March and April. One to three eggs are laid at a time. Eggs are of variable colouring, but are usually pinkish and sporadically marked with dark reddish-brown spots[11] .

3.5 Parasites

The crimson sunbird is a host to Leucocytozoon sp., a group of intracellular blood parasites of birds. Leucocytozoon sp. are known to parasitize other sunbirds, as well as at least three other families: Lybiidae (barbets), Picacthartidae (junglefowl) and Pycnonotidae (bulbuls). However, the exact relationship between the birds and the parasites is yet to be determined[12] .

4. Description and Identification

From Hails and Jarvis (1987)[13] , Jeyarajasingam and Pearson (1999)[14] or Yong, Lim and Lee (2016)[15] unless otherwise stated.

4.1 General Identification

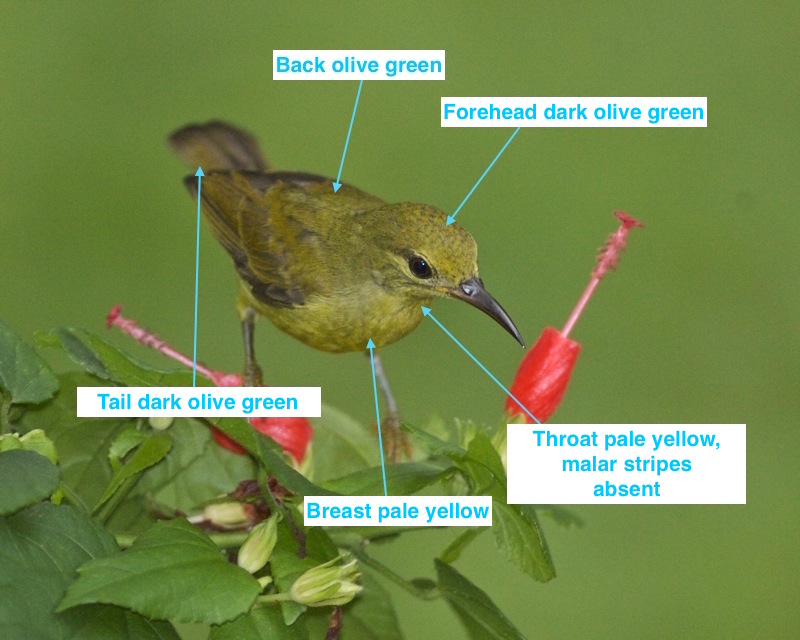

The crimson sunbird is tiny - an adult is only 11cm long on average. It has a thin, down-curved bill of medium length and a brush-tipped tubular tongue, both to facilitate nectar feeding[16] . It also displays sexual dimorphism, with males having the bright crimson colour that gives the bird its vernacular name, and females being more drab. This can be seen from Figures 2a and 2b, which indicate distinctive features of the male and female crimson sunbird for identification purposes. Table 1 below the two figures presents a more detailed description and comparison between the male and the female, and also includes features of the male in eclipse phase - where it has temporary dull plumage after breeding.| Body Part(s) |

Male |

Male eclipse |

Female |

| Forehead |

Dark iridescent green |

Dark olive |

Dark olive green |

| Head, chin, neck |

Bright crimson |

Dark olive |

Dark olive green |

| Bill |

Medium length, thin, down-curved |

Medium length, thin, down-curved |

Medium length, thin, down-curved[17] |

| Throat |

Bright crimson |

Diffused red |

Pale yellow |

| Malar stripes |

Two, dark iridescent violet |

Absent |

Absent |

| Breast |

Bright crimson |

Diffused red |

Pale yellow |

| Belly |

Grey |

Dark olive |

Pale yellow |

| Scapulars |

Bright crimson |

Dark olive |

Pale yellow |

| Primaries and secondaries |

Brown |

Dark olive |

Dark olive green |

| Rump |

Yellow |

Dark olive |

Dark olive green |

| Tail |

Elongate (extends 3cm), iridescent violet |

Not elongate, dark olive |

Not elongate, dark olive green |

4.2 Diagnosis

Due to the distinct sexual dimorphism of the crimson sunbird, males and females are morphologically similar to different heterospecifics. Tables 2a and 2b describe the species similar to male and female crimson sunbirds respectively. All species described have overlapping ranges with the crimson sunbird. However, only the brown-throated sunbird, olive-backed sunbird and purple-throated sunbird can be found in Singapore.

Table 2a. Description of morphologically similar species to male crimson sunbirds

|

Black-throated sunbird (Aethopyga saturata) (NOT FOUND IN SINGAPORE)

|

||

|

Scarlet sunbird (Aethopyga temminckii) (NOT FOUND IN SINGAPORE)

|

Table 2b. Description of morphologically similar species to female crimson sunbirds

|

Brown-throated sunbird (Anthreptes malaccensis)

|

||

|

Olive-backed sunbird (Nectarinia jugularis)

|

||

|

Purple-throated sunbird (Nectarinia sperata)

|

4. Vocalization

The crimson sunbird's call can be described as a high-pitched, sibilant seep-seep. Below is a recording of a crimson sunbird's call from the Central Catchment Nature Reserve in Singapore, retrieved from xeno-canto:

5. Distribution

5.1 Global range

The crimson sunbird is exclusively a resident of southern Asia, but has an extremely large range within that area - its estimated extent of occurrence (EOO) is 4,920,000 km2. Its range covers countries such as India, Bangladesh, China, Myanmar, Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, the Philippines and Indonesia. It has been described as usually common in all those areas, with the exception of Buton Island in Indonesia, where it is described as uncommon or rare[18] . Figure 4 below shows the range map of the crimson sunbird (demarcated in yellow).

|

| Figure 6. Range map of the crimson sunbird. Taken from IUCN. |

5.2 Distribution in Singapore

The crimson sunbird is commonly found in the Central Catchment Nature Reserve, Bukit Timah Nature Reserve, Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve and Bukit Batok Nature Park[19]

7. Conservation Status

7.1 Global status

The crimson sunbird is evaluated as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List[20] as it does not approach the thresholds for Vulnerable classification under various criteria. It has an extremely large range of almost 5 million km2 as mentioned in Section 5, and thus does not approach the threshold for Vulnerable under the range size criterion (EOO <20,000km2). It has a stable population trend, and hence does not approach the Vulnerable threshold under the population trend criterion (>30% decline over 10 years or three generations). Its population size, though unquantified, is not estimated to approach the Vulnerable threshold under the population size criterion (<10,000 mature individuals with an estimated continuing decline of >10% in 10 years or three generations). Therefore, the crimson sunbird is evaluated as Least Concern.7.2 Singapore status

The crimson sunbird is not under any conservation threat in Singapore either. It is listed as 'common' in the 2015 Checklist of the Birds of Singapore compiled by Nature Society Singapore[21] , as well as the Singapore Red Data Book[22] .

8. Taxonomy and Systematics

...mostly for the biologists :)

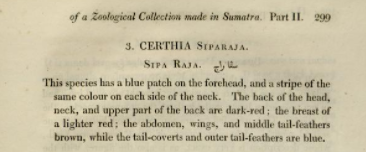

8.1 Original description

The protonym of the crimson sunbird is Certhia siparaja[23] . It was first described by Sir Stamford Raffles in 1822. This description was printed in the Transactions of the Linnean Society of London[24] , and is shown in Figure 7 below.

|

| Figure 7. Screenshot of the original description of the crimson sunbird (Certhia siparaja) from The Transactions of the Linnean Society of London. |

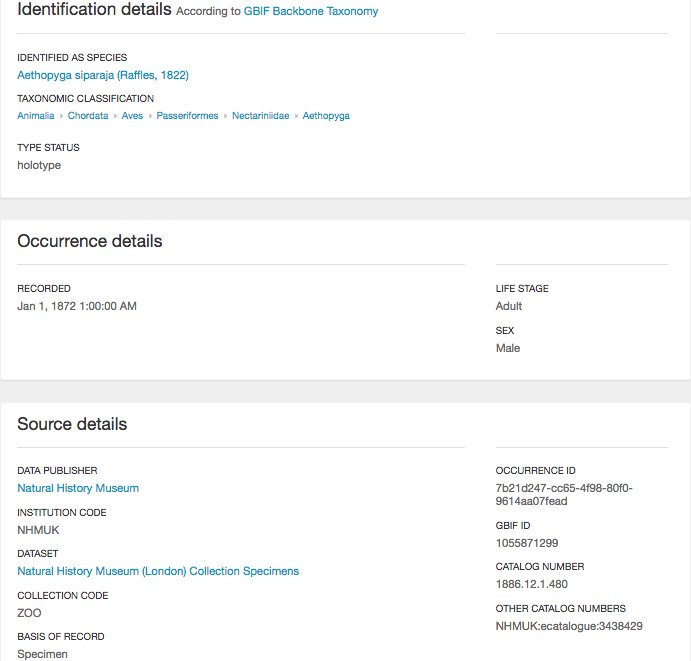

The type specimen of the crimson sunbird was collected in 1872, and is now located in the Natural History Museum of London[25] . Details of the type specimen are shown in Figure 8 below.

|

| Figure 8. Screenshot of details of the crimson sunbird type specimen |

8.2 Taxonomic hierarchy

Below is the taxonomic classification of the crimson sunbird. Taxonomic ranks are not included as they may not provide objective taxonomic information. For more on this, click here.

- Animalia

-- Chordata

--- Aves

---- Passeriformes

----- Nectariniidae (Vigors, 1825)

------ Aethopyga (Cabanis, 1850)

------- Aethopyga siparaja (Raffles, 1822)

[26]

8.3 Subspecies

The crimson sunbird is a polytypic species. Its 15 subspecies are listed in Table 3 below[27] . Aethopyga siparaja siparaja is the only subspecies found in Singapore[28]

Table 3. Description of subspecies of the crimson sunbird and their distributions.

| No. |

Subspecies |

Distribution |

| 1 |

Aethopyga siparaja siparaja (Raffles, 1822) (nominate species) |

Malay Peninsula (south of Narathiwat), Anamba Islands (east of Peninsular Malaysia), Sumatra (except Aceh) and satellite islands, and Borneo and associated small islands (except Natunas). |

| 2 |

A. s. labecula (Horsfield, 1840) |

Bhutan, northeastern India (north West Bengal, Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya, Nagaland, Manipur) and Bangladesh south to Chittagong Hills, east to Myanmar (except in the south), southern China (south Yunnan), northwestern Laos and northwestern Vietnam |

| 3 |

A. s. cara (Hume, 1874) |

South Myanmar and Thailand |

| 4 |

A. s. nicobarica (Hume, 1873) |

South Nicobar Island (Great and Little Nicobars, Kondal and Meroe Islands) |

| 5 |

A. s. tonkinensis (E. J. O. Hartert, 1917) |

Northeastern Vietnam and south China (southeastern Yunnan east to western Guangdong) |

| 6 |

A. s. owstoni (Rothschild, 1910) |

Naozhou Island (southwestern Guangdong) in south China |

| 7 |

A. s. mangini (Delacour and Jabouille, 1924) |

Southeastern Thailand and central and south Indochina |

| 8 |

A. s. insularis (Delacour and Jabouille, 1928) |

Phu Quoc Island, off southern Cambodia |

| 9 |

A. s. trangensis (Meyer de Schauensee, 1946) |

Southern Thailand and northern Malay Peninsula |

| 10 |

A. s. natunae (Chasen, 1935) |

Natuna Islands |

| 11 |

A. s. heliogona (Oberholser, 1923) |

Java |

| 12 |

A. s. flavostriata (Wallace, 1865) |

Northern Sulawesi |

| 13 |

A. s. beccarii (Salvadori, 1875) |

Central, south and southeastern Sulawesi, Kabaena, Muna and Butung |

| 14 |

[A. s. magnifica] (Sharpe, 1876) (Possibly a separate species) |

West-central Philippine Islands, Marinduque, Tablas, Sibuyan, Panay, Negros, Cebu |

| 15 |

[A. s. seheriae] (Tickell, 1833) (Possibly a separate species) |

Himalayan foothills in India from W Himachal Pradesh (Kangra) east to Sikkim and Bhutan, south to northern West Bengal, eastern Bihar,eastern Madhya Pradesh and Orissa (possibly northern Andhra Pradesh), and western Bangladesh |

8.4 Phylogeny

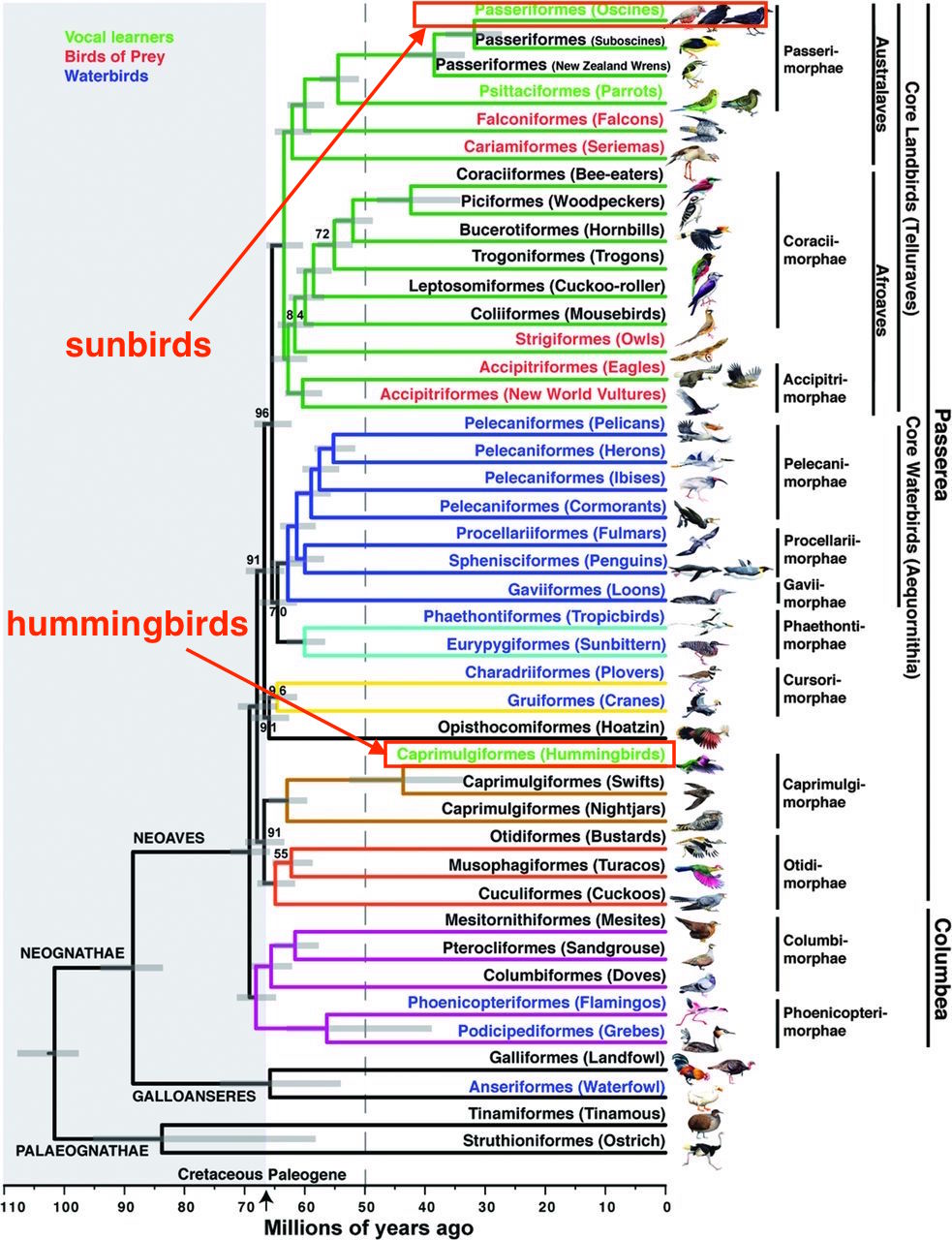

In 2014, Jarvis et al. performed a genome-scale phylogenetic analysis of 48 avian species representing all orders of Neoaves using phylogenomic methods created to handle genome-scale data. The total evidence nucleotide alignment partitioned by data type (introns, UCEs, and first and second exon codon positions) analyzed using Maximum Likelihood analysis under the GTR+GAMMA model of sequence evolution yielded the Total Evidence Nucleotide Tree, a highly-resolved phylogenetic tree that confirmed previously undetermined sister or close relationships[29] .

The order Passeriformes can be split into New Zealand wrens, suboscines and oscines (commonly referred to as songbirds). The crimson sunbird belongs to the oscines. Figure 9 below illustrates the position of the crimson sunbird in the Total Evidence Nucleotide Tree[30] . (In reference to Section 1.3, the position of hummingbirds is illustrated as well, showing how distant the relationship between sunbirds and hummingbirds actually is.)

|

| Figure 9. Total Evidence Nucleotide Tree by Jarvis et al. (2014). Edited by Chai Wen Xuan |

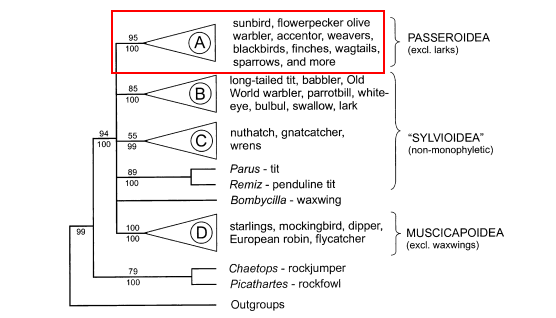

Within the oscines, there are three superfamilies - Sylvioidea, Muscicapoidea and Passeroidea. Ericson and Johansson (2003)[31] sequenced multiple nuclear and mitochondrial genes and analyzed the data via parsimony jackknifing and Bayesian analysis to obtain four main clades, as shown in Figure 10 below.

|

| Figure 10. Simplified phylogenetic relationships among the oscines, by Ericson and Johansson (2003). Edited by Chai Wen Xuan |

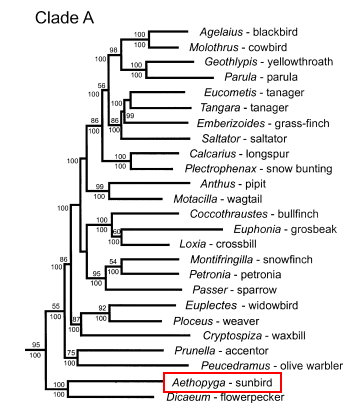

Monophyly of this clade is supported in both parsimony jackknifing (94%) and Bayesian analysis (100%), and the maximum likelihood tree in Figure 11 below shows that the Aethopyga sunbirds are the first outgroup, together with the flowerpeckers[32] .

|

| Figure 11. Maximum likelihood tree by Ericson and Johansson (2003) illustrating split of Aethopyga from the other genera in clade A. Edited by Chai Wen Xuan |

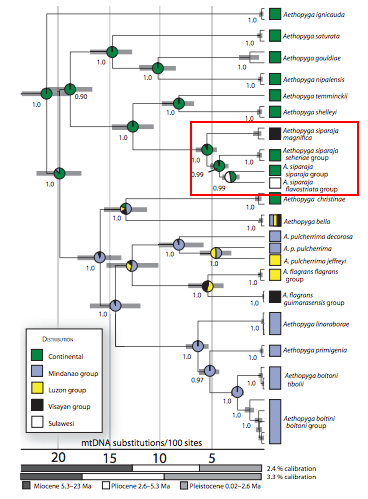

Hosner, Nyári and Moyle (2013)[33] then reconstructed the phylogenetic relationships within the Aethopyga genus through further mitochondrial and nuclear DNA sequencing. They used maximum likelihood ancestral state biogegraphical reconstructions to examine the ancestral distribution and colonization history of Aethopyga. To determine whether the diversification at each node occurred within a continent, across a shallow-water barrier, across a deep-water barrier or within an island, they used statements based on the phylogeny, current distribution of species and bathymetric reconstructions. Ultimately, they derived the position of Aethopyga siparaja, as shown in Figure 12 below.

|

| Figure 12. Ancestral state reconstruction by Hosner et al. (2013) to derive the position of Aethopyga siparaja. Edited by Chai Wen Xuan |

However, the figure also shows that Aethopyga siparaja could be treated as a complex of geographically separated species (or allospecies). The most obvious example would be the subspecies Aethopyga siparaja magnifica (mentioned as possibly a separate species in Section 8.3 above) which appears to be the sister group of all the Aethopyga siparaja subspecies. Prior research on isolation[34] , as well as molecular results[35] , has supported the placement of A. s. magnifica as a separate sister species to all other A. siparaja subspecies. Further splits within A. siparaja might be warranted but similarly rigorous experimentation and DNA sequencing will first have to take place.

8.5 DNA barcoding

Genbank contains many nucleotide sequences for the crimson sunbird, such as the NADH dehydrogenase subunit 2 (ND2) gene, NADH dehydrogenase subunit 3 (ND3) gene, recombination activating protein 1 (RAG1) gene, ornithine decarboxylase (ODC) gene and the cytochrome b (cytb) gene. They can be found here. However, do note that they are not official barcodes as they were not sequenced from the cytochrome c oxidase I (COI) gene.

9. Glossary

nectarivorous: feeds mainly or exclusively on nectar

convergent evolution: the process whereby organisms that are not closely related develop similar traits, due to them adapting to similar environments and ecological niches

ecological niche: the specific role a species plays in its environment

sexual dimorphism: a distinct difference in size or physical appearance between both sexes of the same species

heterospecific: of a different species (opposite: conspecific)

sibilant: characterized by a hissing sound

extent of occurrence: total surface area over which a species can be found naturally

protonym: unofficial (usually first) name for a new species

type specimen: the individual specimen (or set of specimens) on which the description and name of a new species is based

polytypic: contains more than one taxonomic category of the next lower rank (opposite: monotypic)

10. Additional information

Crimson sunbird in MacRitchie Reservoir: https://youtu.be/CWwc8umb7YU

Male crimson sunbird mating display: https://youtu.be/uzY0dZ1dfIU

More crimson sunbird vocalization recordings: http://www.xeno-canto.org/species/Aethopyga-siparaja

11. Literature Cited

- ^ Web, A. (2014). Crimson Sunbirds.

- ^ Chew, H. (2015). Is the crimson sunbird Singapore's national bird? Er... not official yet. The Straits Times. Retrieved from http://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/environment/is-the-crimson-sunbird-singapores-national-bird-er-not-official-yet

- ^ Jarvis, E. D., Mirarab, S., Aberer, A. J., Li, B., Houde, P., Li, C., ... & Suh, A. (2014). Whole-genome analyses resolve early branches in the tree of life of modern birds. Science, 346(6215), 1320-1331.

- ^ Marshall Cavendish Corporation (2001). Endangered wildlife and plants of the world (1st ed., p. 1423). New York: Marshall Cavendish.

- ^ Hails, C. & Jarvis, F. (1987). Birds of Singapore (pp. 146-149). Singapore: Times Editions.

- ^ Cheke, R. & Mann, C. (2001). Sunbirds: a guide to the sunbirds, flowerpeckers, spiderhunters and sugarbirds of the world (pp. 345-346). New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press.

- ^ Cheke, R. & Mann, C. (2001). Sunbirds: a guide to the sunbirds, flowerpeckers, spiderhunters and sugarbirds of the world (pp. 345-346). New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press.

- ^ Cheke, R. & Mann, C. (2001). Sunbirds: a guide to the sunbirds, flowerpeckers, spiderhunters and sugarbirds of the world (pp. 345-346). New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press.

- ^ Web, A. (2014). Crimson Sunbirds.

- ^ Cheke, R. & Mann, C. (2001). Sunbirds: a guide to the sunbirds, flowerpeckers, spiderhunters and sugarbirds of the world (pp. 345-346). New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press.

- ^ Cheke, R. & Mann, C. (2001). Sunbirds: a guide to the sunbirds, flowerpeckers, spiderhunters and sugarbirds of the world (pp. 345-346). New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press.

- ^ Jones, H. I., Sehgal, R. N., & Smith, T. B. (2005). Leucocytozoon (Apicomplexa: Leucocytozoidae) from West African birds, with descriptions of two species. Journal of Parasitology, 91(2), 397-401.

- ^ Hails, C. & Jarvis, F. (1987). Birds of Singapore (pp. 146-149). Singapore: Times Editions.

- ^ Jeyarajasingam, A. & Pearson, A. (1999). A field guide to the birds of West Malaysia and Singapore. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Yong, D., Lim, K., & Lim, T. (2016). A Naturalist's Guide to the Birds of Singapore (2nd ed., p. 151). Oxford: John Beaufoy Publishing.

- ^ Web, A. (2014). Crimson Sunbirds.

- ^ Web, A. (2014). Crimson Sunbirds.

- ^ IUCN Red List,. (2016). Aethopyga siparaja (Crimson Sunbird). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 9 November 2016, from http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/22718093/0

- ^ Yong, D., Lim, K., & Lim, T. (2016). A Naturalist's Guide to the Birds of Singapore (2nd ed., p. 151). Oxford: John Beaufoy Publishing.

- ^ IUCN Red List,. (2016). Aethopyga siparaja (Crimson Sunbird). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 9 November 2016, from http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/22718093/0

- ^ Nature Society (Singapore) Bird Group Records Committee (2015). Checklist of the Birds of Singapore (2015 Edition)

- ^ Davison, G. W. H., Ng, P. K. L. and Ho, H. C. (2008). The Singapore Red Data Book: Threatened Plants and Animals of Singapore. Second Edition.

- ^ Avibase (n.d.). Aethopyga siparaja - Avibase. Avibase.bsc-eoc.org. Retrieved 9 November 2016, from http://avibase.bsc-eoc.org/species.jsp?lang=EN&avibaseid=EC22F3AA71EC2F48

- ^ Raffles, T. S., (1822). Transactions of the Linnean Society of London. [online] v.13 (1822), p.299. Retrieved 9 November 2016, from http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/13692#page/331/mode/1up

- ^ GBIF,. Occurrence Detail 1055871299. Gbif.org. Retrieved 9 November 2016, from http://www.gbif.org/occurrence/1055871299

- ^ ITIS (n.d.). ITIS Standard Report Page: Aethopyga siparaja. [online] Retrieved 9 November, from https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=558466#null

- ^ Web, A. (2014). Crimson Sunbirds.

- ^ Type the content of your reference here.

- ^ Jarvis, E. D., Mirarab, S., Aberer, A. J., Li, B., Houde, P., Li, C., ... & Suh, A. (2014). Whole-genome analyses resolve early branches in the tree of life of modern birds. Science, 346(6215), 1320-1331.

- ^ Jarvis, E. D., Mirarab, S., Aberer, A. J., Li, B., Houde, P., Li, C., ... & Suh, A. (2014). Whole-genome analyses resolve early branches in the tree of life of modern birds. Science, 346(6215), 1320-1331.

- ^ Ericson, P. G., & Johansson, U. S. (2003). Phylogeny of Passerida (Aves: Passeriformes) based on nuclear and mitochondrial sequence data. Molecular phylogenetics and evolution, 29(1), 126-138.

- ^ Ericson, P. G., & Johansson, U. S. (2003). Phylogeny of Passerida (Aves: Passeriformes) based on nuclear and mitochondrial sequence data. Molecular phylogenetics and evolution, 29(1), 126-138.

- ^ Hosner, P. A., Nyári, Á. S., & Moyle, R. G. (2013). Water barriers and intra‐island isolation contribute to diversification in the insular Aethopyga sunbirds (Aves: Nectariniidae). Journal of Biogeography, 40(6), 1094-1106.

- ^ Lohman, D. J., Ingram, K. K., Prawiradilaga, D. M., Winker, K., Sheldon, F. H., Moyle, R. G., ... & Astuti, D. (2010). Cryptic genetic diversity in “widespread” Southeast Asian bird species suggests that Philippine avian endemism is gravely underestimated. Biological Conservation, 143(8), 1885-1890.

- ^ Cheke, R. A., & Mann, C. (2008). Family Nectariniidae (sunbirds).